This bit of wisdom I learnt at school, even if it was not at my own. It was at New Delhi’s brilliant Sanskriti School which invited me to give away prizes to its students this July. They had posters with quotes from great people which, unusually, included one from the one-eyed Israeli general, Moshe Dayan. It read: “If you want to make peace, you don’t talk to your friends. You talk to your enemies.” I Googled it later, and the quote was accurate. There were other interesting entries as I trawled years of war and peace in the Middle East. There was also a similar peacenik quote from another unlikely Israeli, Dayan’s doughty prime minister Golda Meir: “A leader who doesn’t hesitate before he sends his nation into battle is not fit to be a leader.”

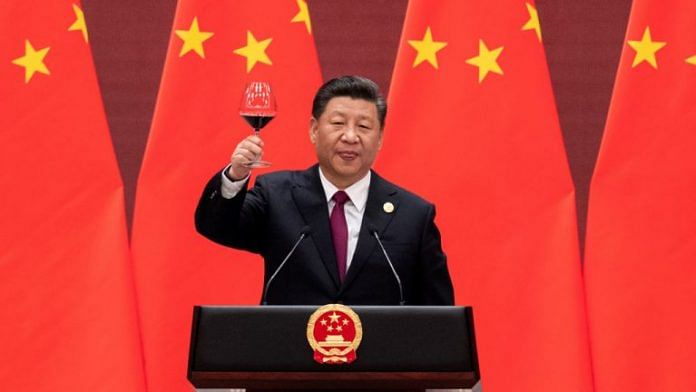

Why are we losing our way in old Middle East history when our focus should be on Japan, China, America, even a bit on Nepal, Australia and its uranium thrown in, all already hailed by a breathless media (particularly news TV) and most of the commentariat about our new government and its prime minister’s foreign policy conquests? Why be such a spoiler just when Narendra Modi is wowing the US? Because there is more to foreign policy than the mere pomp and form of summits and foreign visits – and the sum of all high diplomacy for India still remains strategic. Which, you must acknowledge in fairness, Modi understands. That is why the first big visit to Japan, and then Pranab Mukherjee’s presence in Vietnam almost when China’s Xi Jinping was landing in India’s new power capital, Ahmedabad. We were waving the flag in the two capitals most suspicious of Beijing in its own front yard. The message was not lost on the Chinese.

They responded in a manner we were not prepared for. Timed perfectly with Xi’s arrival was that of nearly a thousand barely armed PLA soldiers in Ladakh’s Chumar area. Like India’s Japan and Vietnam visits, this was easy to read given its nature and timing. To fantasise that it was just the PLA flexing its muscles, probably to spoil Xi’s party, will only convince China apologists and a small, but noisy band of ultra nationalists who suffer from terminal Pakistanitis and believe that every army in the neighbourhood calls the shots and every civilian leader is an Asif Ali Zardari. This fantasy conveniently fits into India’s current testosterone-laden stereotypes and attempts to underplay the most severe diplomatic snub to our country in a very long time. That, at a time when we have finally elected a strong leader.

Also read: ‘Most difficult phase’ — Jaishankar says India-China ties ‘significantly damaged’ this year

The Chinese used the visit to puncture our balloon. They walked in and out of what we believe to be our territory while our new prime minister had to keep feting in his hometown, and smiling at, their president. Would we have responded with the same calm if this was Pakistan? There, we get so touchy, we call off talks because their envoy has tea with Hurriyat leaders on his own diplomatic premises. What is our approach then, kick the smaller neighbour for the most trivial impertinence, and turn the other cheek when the big boy slaps one? Modi is astute, and far from delusional or foolish. He would know that in 1962, the Chinese had to launch an invasion to show who was the boss, now Xi has achieved it with just a three-day state visit. Modi should be smarting, and it must nag him through his five days in America. A restatement of the four pillars of India’s supreme national (strategic) interest is in order here. First, India’s territory must not shrink any further. Second, its preeminence in South Asia must remain unchallenged, and grow. Third, its global stature should rise. And fourth, India must have full control and autonomy over its nuclear and missile assets. China has now shaken the first three, and told us that it doesn’t particularly bother about the fourth. It has also, and I suspect consciously, challenged India’s new hyper-nationalistic surge, reminding us we haven’t quite earned that right yet.

This forces India to see itself in a different strategic light. Modi is now in America, conscious that while his rise has brought a new confidence, our strengths and weaknesses remain essentially the same as under his less spectacular predecessor. Elections change governments and the national mood, but they can’t change realities of geopolitics. That calls for hard work, patience and, most importantly, calm. There is a pattern to China’s actions: it is testing India’s resolve. I am aware of the outrage I would draw if I suggested that the previous government had handled similar provocations more skillfully, yet resolutely. It stared the Chinese down when they nearly served an ultimatum that India bar the Dalai Lama from visiting Tawang (November 2009). And when there was a similar border ingress on the eve of Li Keqiang’s visit, in May 2013, it insisted that PLA clear out if the visit was to go on. Of course this time the Chinese left nothing to chance. Action began once Xi was in India, and turning back a head of state would be a provocation just short of declaration of war.

At one of his rare interactions with editors, Manmohan Singh explained India’s strategic predicament like a statesman. Though he had meant it to be off-record, one editor headlined it the next day, so I am breaking no confidence by referring to it now. China, Singh said, uses a very low-cost strategy of “triangulation” to keep India in its place. Briefly, this means encouraging Pakistan to keep us off-balance, thereby diminishing ours, and enhancing China’s pre-eminence. As long as Pakistan keeps us thus trapped, China sees no urgency to settle the borders with us. China values India as a market for its cheap manufacture, from rakhis to turbines. Chinese FDI in India, at last count, was less than Poland’s. China sits pretty, defining its relationship with us in purely one-sided mercantilist terms while using Pakistan to limit and define our strategic reach. India needs ideas to break out of this chakravyuh.

Given India’s post-May 2014 mood, this may sound like a radical idea, but it really isn’t. The only way out of this triangulation is to first make progress with Pakistan, and to large-heartedly resolve outstanding issues with other neighbours, including the land border agreement with Bangladesh. We know the Pakistanis are not helpful, that their power structure is messed up, etc. But India and the rest of the world still have more leverage there than with China. The thing on the top of Modi’s mind in the US should be to build a global coalition of peace to change the nature of Pakistan’s polity and society. This is one of the most commonly shared global strategic ideals and India needs a virtuous alliance around America and, who knows, in the long run even China. This is precisely what Vajpayee-Brajesh Mishra and Manmohan-Shankar Menon had worked on in the past and, in each case, come close to a breakthrough with Islamabad.

Also read: After HCQ, India pushes vaccine diplomacy in S. Asia as China rushes in with its Covid shots

More immediately, India needs to make quiet diplomatic moves to restore the conversation with Pakistan and to also lower the public opinion bar on engaging with its most important neighbour. Today we flatter ourselves when we use that description for China instead. The Chinese, and we know well enough now after Xi and Chumar, are not impressed with that, nor with our nukes and laugh at the raising of a mountain assault corps minus artillery in the east. At this point, we can also put the quotes from the two famous Israelis in context. If you want peace, you have to talk to your enemies, the more difficult being the most urgent. The new establishment and its voters admire Israel and its fortitude and wisdom. If even Israel’s most successful military leaders are telling you to go, talk to the enemy, beware of the consequences of war, you know you need a rethink.

Another page from my Vajpayee diary: I do not believe I have come across a leader calmer in a crisis than Atal Bihari Vajpayee. I had sought time from him one Saturday afternoon while Kargil skirmishes were at their most intense. I reported at the appointed hour, three in the afternoon. I was ushered into the anteroom. Three-thirty, then four, had they forgotten that I was waiting? An aide came in to comfort me. “The PM has not risen from his siesta, seems to have over-slept,” he said with a touch of amused embarrassment.

Around 4.30 pm, I was escorted in. Vajpayee greeted me with disarming, mock exaggerated horror. “Arrey, arrey, arrey, hum se anarth ho gaya, sotey reh gaye hum aur Shekharji ko pratiksha karni padi, ab kya hoga hamara?” (What an awful thing I have done, I overslept and made you wait, what will be my punishment?) I was in splits already but seized the moment and asked, with equally mock concern, “Kintu Atalji, Kargil mein yudh, aur aap do ghante so rahe hain dopahar mein?” (A war is raging in Kargil, and the PM enjoys a two-hour siesta?)

“Haan, theek kaha aapne,” Atalji was game, his eyes wide with “horror”. “A war is on, bring me a rifle, Atalji ladne jaayenge ab Kargil mein, desh mein jawanon ki kami jo ho gayi hai.” (There is such a paucity of young jawans in India, Atalji will go fight in Kargil.) We both laughed a little, he tucked into a pastry, and I got a lesson in how a strong, confident leader keeps his calm in grave crisis.

Also read: China set to bail out Iraq with multibillion-dollar oil deal