What Vivek Agnihotri’s latest film The Kashmir Files wants to convey is correct in essence. There is zero doubt or question that between around November 1989 and May 1990, almost all of the native Hindus from the Kashmir Valley, mostly Kashmiri Pandits, had been brutally forced out by Islamised forces in an Indian equivalent of ethnic cleansing.

Many were killed, beginning with old social activist and advocate Tika Lal Taploo in September 1989. Unattributed advertisements appeared in local Urdu newspapers, asking Hindus to leave. It’s all a reality that should be well known to two generations of Indians.

Historians, story-tellers, filmmakers most of all, will each find their own version of the truth. In a polarised and traumatised environment, they will also focus on what affects them the most. As Clint Eastwood showed us, Iwo Jima had two versions of the truth (Flags of Our Fathers/Letters From Iwo Jima). But nobody can question the ferocity of the battle there, and the heroism of professional soldiers.

It is ridiculous and tragic, therefore, that The Kashmir Files debate has become trapped in questions like how many Kashmiri Pandits were actually killed? Was the number in two figures, three, four, five, six, or in some claims, seven? Was it an ethnic cleansing, forced exodus, genocide, another holocaust?

This argument will yield nothing. What matters 32 years after that great national tragedy is that we are still reducing it to an argument over the scorecard of the killings. The numbers, any which way, will not lighten or deepen the tragedy. And the national shame involved in a large community — a minority in its home state — being bullied out of it, in a democratic republic with armed forces, police and intelligence agencies that rank among the most formidable in the world.

That one side feels free to add zeroes to the toll in a manner so cavalier, and the other would shed tears over the atrocities on the Rohingya in Myanmar on the one hand but asks that the Kashmiri Pandit issue be treated with a light touch, are two sides of the same coin of irony. Nothing I am saying here endorses or denounces the film. I haven’t seen it yet. For the same reason that I haven’t seen Ranveer Singh and Alia Bhatt starrers 83 and Gangubai Kathiawadi, respectively. I am still too Covid-scarred to step into a cinema hall.

Whatever the quality of film-making or research, The Kashmir Files’ has made a positive contribution by exposing a lacerating but hidden 32-year wound. The downside is the scary and shameful bigoted response by audiences in cinema halls. The demonising of the entire community and calls for reprisals on innocent Muslim families. Brilliant journalist and author Rahul Pandita, who wrote the landmark account of the 1989-90 atrocity in his ‘Our Moon has Blood Clots’ but is now attacked viciously on social media for raising some arguments over facts and treatment with the filmmaker, says it is a kind of catharsis for Kashmiri Pandits after 32 years, an acknowledgment of their plight, and they must have it. That’s an important point, and worth exploring further.

Also Read: Rocket Boys’ crime on history: Inventing Muslim villain, stealing Meghnad Saha’s identity

In 75 years since Independence, India has endured many sizeable tragedies. Nor is India unique in having lived through violent evolution. But one common and unfortunate trait across the subcontinent is our inability to look the truth in the eye. Accept, if not confess what we’ve done wrong; find closure for both, the victims and the perpetrators, and hope to move on.

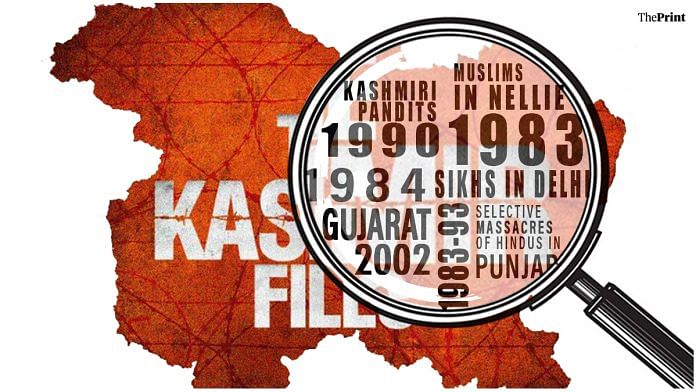

Our culture and civilisation takes a circular view of issues. Our arguments go on, and on, and on. If, buts, ‘root causes,’ whataboutery and worse. The shameful fact is, as a nation and a system of laws, we have failed to bring to account perpetrators of our biggest mass crimes. From the many large communal riots across decades to the six-hour mass cull of Muslims in Nellie, 1983; Sikhs in Delhi, 1984; Kashmiri Pandits, 1990; massacres of Hindus in Punjab, 1983-93; and Muslims in Gujarat, 2002.

What is settled by law doesn’t necessarily bring closure to an issue. But it helps. In our system on the other hand, every self-inflicted calamity becomes an eternal, partisan argument. In some cases, it pretends to fade away, as with Nellie. The reason I said ‘pretends to’ is that a mass injustice pushed under the carpet may be temporarily forgotten, but is never forgiven. It goes into oral history and becomes a never-ending blood feud. That is our bane.

Such grievances never go away. Be prepared for a The Kashmir Files-like film on Partition bloodshed in the Bengal one of these days, and the consequences it unleashes.

Societies and communities don’t forget their saddest moments, but they can forgive. No truth is too inconvenient to be put aside. Once you accept the plight of Kashmiri Pandits, apologise for the fact that their nation failed to give them due protection under law and Constitution, you can take the argument further. That, the same mass criminality by terrorists, invited the wrath of the entire might of India’s Arm and security agencies. That since then, nearly 20,000, mostly Kashmiri Muslims, have been killed — by the armed forces, and many by Pakistan-controlled Muslim terrorists. That there will be no durable peace in the Valley until the Pandits can feel safer there, as fellow Kashmiris, not in West Bank-style Jewish enclaves.

Also Read: Read my lips, I’m hurting, says Pakistan’s National Security Policy. What it means for India

India’s handling of Kashmir has been knee-jerk, seeking cynical quick-fixes. It’s personified best by Yasin Malik. On 25 January 1990 he was alleged to have led a terror squad that assassinated four unarmed IAF officers waiting to board a bus in Srinagar and two other, civilian women in the same queue. The case came up for trial only 30 years later, in 2020, and charges were framed. Why?

It isn’t as if Malik had absconded to Pakistan. He was here all the time, most of which was spent in comfort under lavish care of the ‘agencies’ who thought they could now repackage him has a terrorist-turned-man of peace. This, when he never denied that he had killed those IAF officers. In a full interview on BBC ‘Hard Talk’ he repeatedly asserted, “I was then in armed struggle, they were Indian soldiers and a fair target”.

For many spells, he had also been the darling of the peacemakers. Almost 25 years ago, while I was still a relatively new editor of The Indian Express, a widely respected activist (I’m not naming her because her own position has changed radically since) called me to persuade me to join a delegation led by the late Kuldip Nayar to Srinagar to “save this young boy (Yasin Malik) who’s so invaluable for peace… that agar yeh bachcha mar gaya toh bahut tragedy ho jayegi”.

It was easy for me to get out of it by simply stating the fact that The Indian Express code of ethics barred all its journalists from participating in any advocacy except on media freedom issues. But I so wished I had spoken the truth. That I found the idea of sucking up to a mass killer of innocent civilians and unarmed IAF officers revolting. And that if this was the way they were searching for peace, they will only make India angrier. How much angrier, we unfortunately see in theatres playing The Kashmir Files.

For any catharsis, Yasin Maliks of any faith, of all our mass injustices, must be brought to justice. The Germans converted old Nazi concentration camps into solemn memorials without airbrushing, so future generations would learn never to fall in the same trap. But that was only after the key Nazi mass killers were hunted down and punished.

To live in denial is to be locked in a vicious circle of injustice. As Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel said, “if we forget, the dead will be killed a second time”. This applies to all mass injustice. It’s a waste to argue over whether any of these was an exodus, ethnic cleansing, pogrom, genocide or a holocaust.

Also Read: India can’t alienate its 20 crore Muslims, not when Taliban are finding legitimacy, not ever