This is Part 2 of a two-part series. You can read Part 1 here.

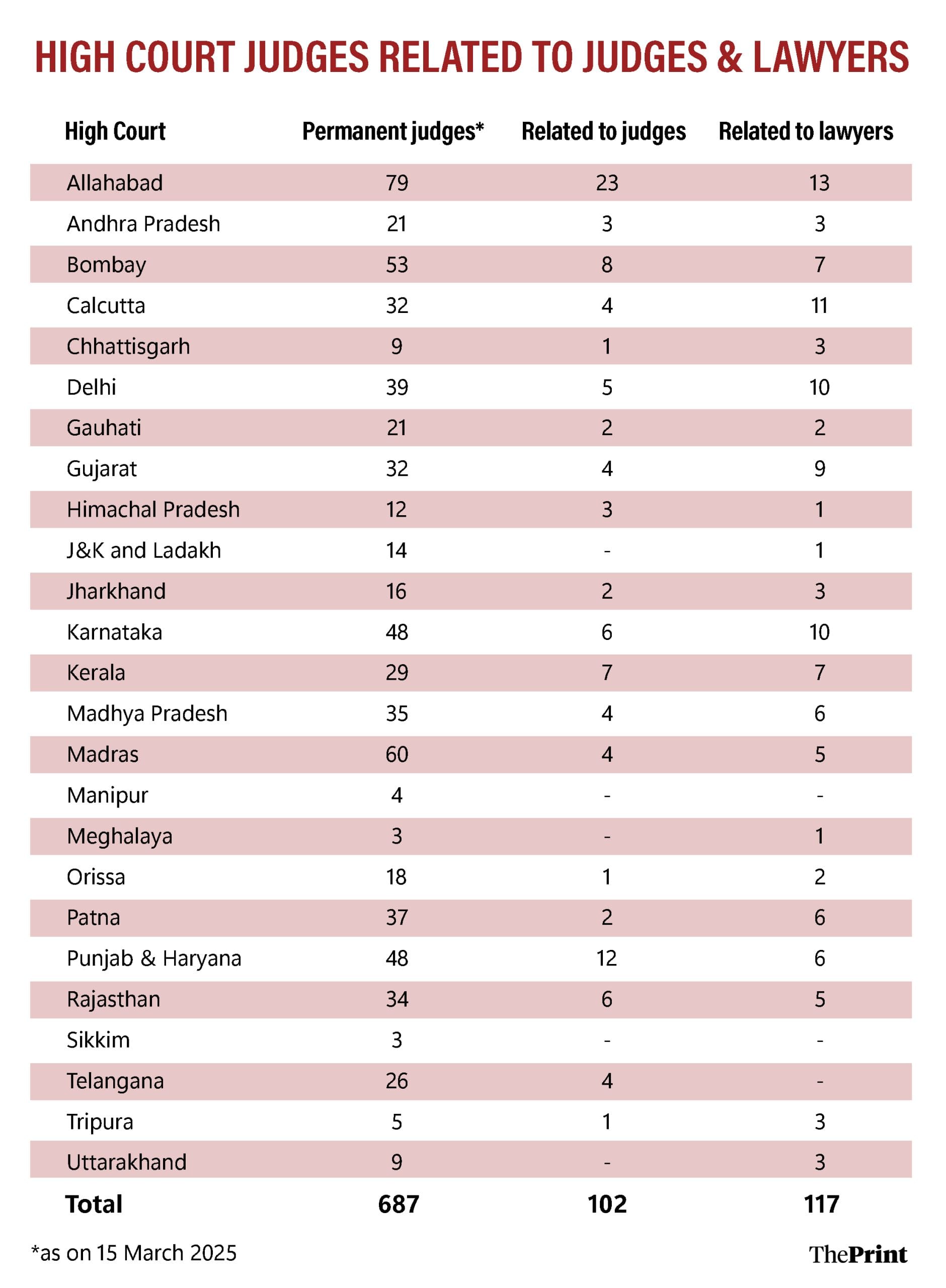

New Delhi: One of every three sitting high court judges in India is related to a sitting or former judge, or comes from a family of lawyers. Of the total 687 permanent judges of the 25 high courts in India as of 15 March, 2025, at least 102 judges are related to former or sitting judges, and another 117 are judges whose fathers, grandfathers or relatives were members of the legal fraternity, an investigation by ThePrint has found.

In the first part of this two-part series, ThePrint explained how at least 30 percent of sitting judges of the Supreme Court are related to former judges, and another 30 percent were second- or third-generation lawyers before their elevation.

The data of the high court judges has been taken as it stood till the second week of March. The information has been collected from publicly available sources, as well as sources within the Supreme Court, and the respective high courts from where the judges were elevated.

Former chief justice of Madras High Court and Meghalaya High Court, Justice Sanjib Banerjee points out that, traditionally, there have been families where the legal profession has been handed down several generations, particularly in metropolitan cities.

So these numbers, he says, are not an anomaly.

“But appointments and elevations should be strictly on merit. Unfortunately, that may not always be the case…When it comes to appointments, I’ve seen in several cases where children of judges have not made too much of a mark in the profession, yet they are singled out,” he asserts.

Justice Banerjee says when he was a part of a high court Collegium, he resisted such attempts at recommending names of children of former judges for elevation to the bench. “I succeeded initially but I’ve seen the same names go through after I was out of the Collegium of that high court,” he told ThePrint.

There were several names that Justice Banerjee says he advocated against for elevation to the Calcutta High Court, because he “did not think they were fit enough competence and temperament wise”. While Justice Banerjee was appointed as a judge of the Calcutta High Court in 2006, he served as the chief justice of Madras High Court from January 2021, before being transferred to the Meghalaya High Court in November 2021.

He believes that the appointment system of judges “is terrible at the moment”. However, he warns against dismantling of the Collegium system of appointments “till we have something which is better and ensures that the primacy of the judiciary in appointments remains and the independence of the judiciary is not curbed”.

Former Madras High Court judge Justice K. Chandru says that a review of the last 75 years of appointments in the Supreme Court and various high courts “will clearly show there was a rampant inbreeding in the positions of power in the higher judiciary notwithstanding the constitutional bar under Article 16(2) where the State had assured no citizen will be discriminated on grounds of descent, caste, religion, race, place of birth or residence”.

“It’s a pity that even after 75 years of the existence of a democratic republic judiciary with the promise of equality, still the same situation continues,” he told ThePrint.

Also Read: Unclean & ill-equipped—the ‘sorry state’ of women’s washrooms in Delhi’s district courts

High court judges: Judicial family trees

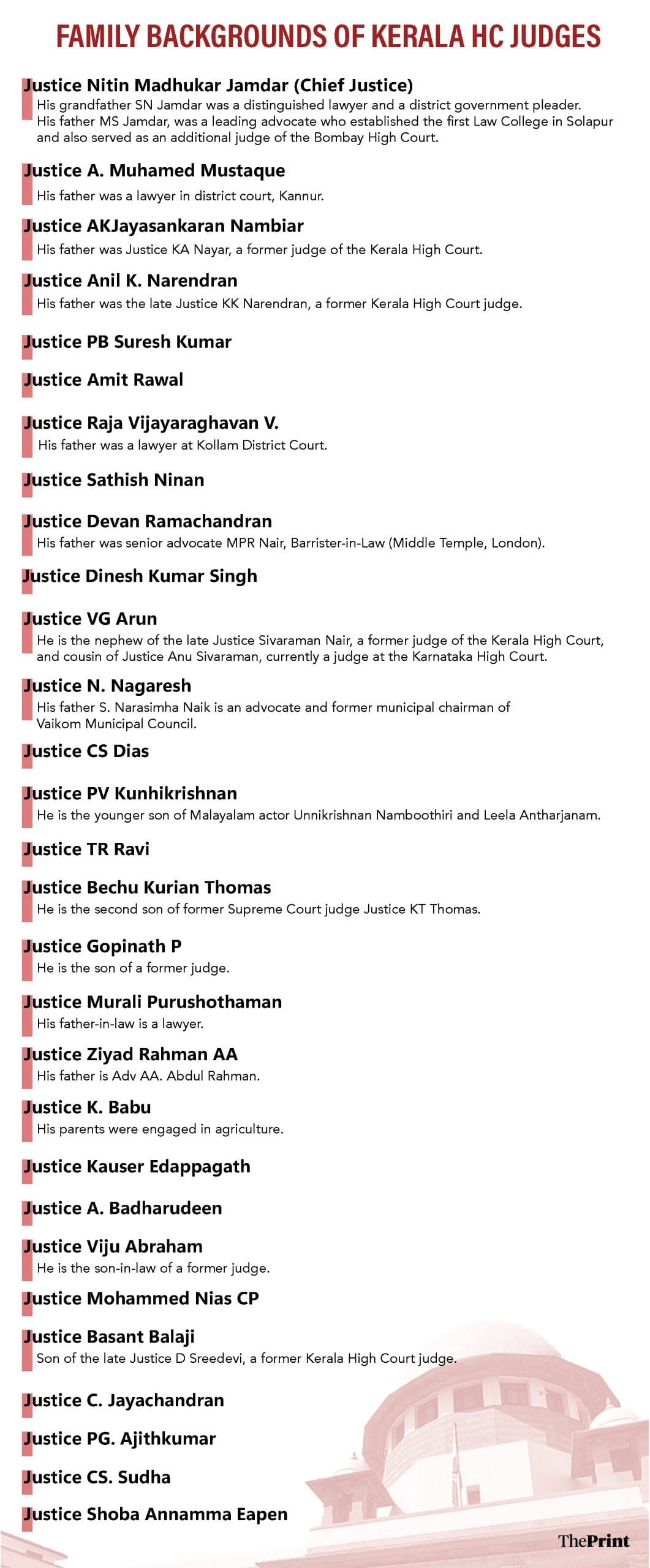

A more detailed look into the families of sitting high court judges also reveals a complex judicial family tree that has branches intertwined over generations and among courts.

For instance, at the Allahabad High Court, Justice Deepak Verma is the brother-in-law of former Supreme Court judge Justice Ashok Bhushan. Justice Vivek Kumar Birla’s son is married to the daughter of Justice Alok Mathur. Justice Ashwani Kumar Mishra’s brother Ajay Kumar Mishra is an Advocate General of Uttar Pradesh. Justice Mishra’s sons Ashutosh and Vinayak are both lawyers, as are Ajay Kumar Mishra’s two sons, Vandit and Vrindavan. Vandit is married to the granddaughter of the late Justice Giridhar Malaviya, who was the grandson of social reformer and freedom fighter Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya.

The Delhi High Court is another case in point. Justice Manmeet Pritam Singh Arora’s sister is married to Justice Anish Dayal.

At the Madhya Pradesh High Court, Justice Vishal Mishra is the brother of former Supreme Court judge, Justice Arun Kumar Mishra. Their father was Justice Hargovind Mishra, a former judge of Madhya Pradesh High Court.

Besides, there are at least three couples who are sitting high court judges as well. For instance, at the Rajasthan High Court, Justices Pushpendra Singh Bhati and Nupur Bhati are married to each other; so are Justices Mahendar Kumar Goyal and Shubha Mehta.

At the Madras High Court, a judge-couple—Justice K. Murali Shankar and Justice T.V. Thamilselvi—was sworn in together in 2020. Both are sitting judges.

In 2019, another judge-couple—Justices Vivek Puri and Archana Puri were sworn in together as judges of the Punjab and Haryana High Court. While Justice Vivek Puri retired in January last year, Justice Archana Puri continues to serve as a judge. Her father Harkrishan Lal Soni was an eminent lawyer in Ludhiana.

Overall, the numbers may be higher than 32 percent out of the 687 high court judges. This list mentions just the names and families that could be confirmed through public information and reliable sources directly spoken to by ThePrint.

The percentages of judges coming from legal backgrounds are higher in a few high courts as compared to others.

For instance, at the Punjab and Haryana High Court, 39 percent of sitting judges are either related to former judges, or had lawyers as parents or relatives. At Kerala High Court, this figure stands at 48 percent.

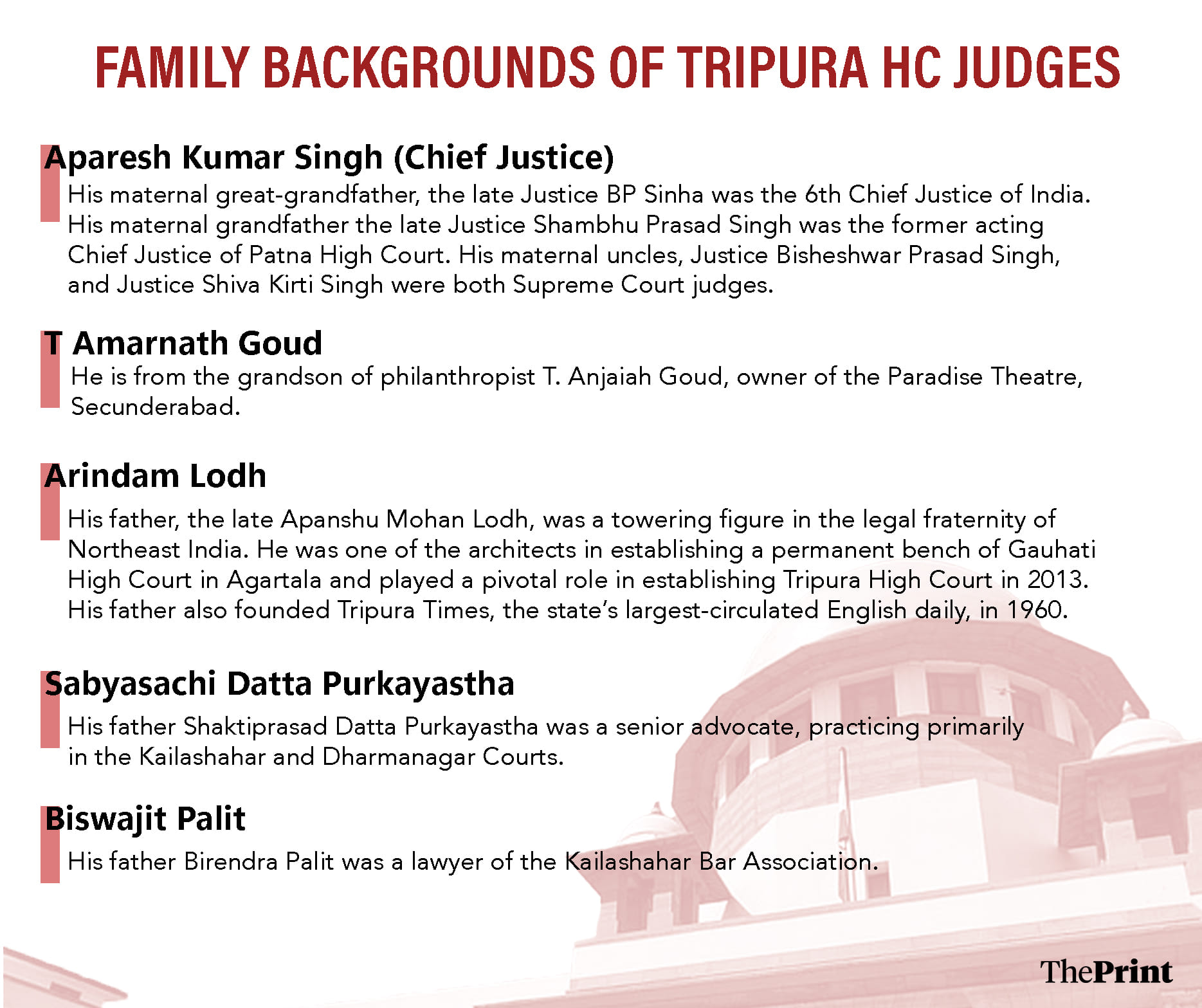

In Tripura High Court, 4 out of the total 5 judges have judicial and legal backgrounds.

‘Uncle judges’

Several relatives of sitting high court judges are practicing lawyers, often in the same high court, or have studied law.

At the Allahabad High Court, at least 24 judges out of the total 79 have children or relatives who are lawyers. At Himachal Pradesh High Court, 6 out of 12 judges have relatives who are lawyers. At Chhattisgarh High Court, 5 out of 9 judges have children who are either lawyers, or are studying law.

Similar connections and networks are visible in other high courts as well. Take Justice Pankaj Purohit of Uttarakhand High Court, for instance. His two sons are both lawyers, and so is his niece. One of the sons practices in Delhi, while the other practices in Nainital. Both the son’s wives are also lawyers. His niece’s husband is also a lawyer, so is the husband’s father, the father-in-law’s brother, the brother’s son and daughter-in-law—all of whom practice in Uttarakhand High Court.

At Gujarat High Court, Justice Mauna M. Bhatt’s husband and brother are senior lawyers, so is her father-in-law but he practices at the Supreme Court. Her husband’s brother and sister are both lawyers as well, so is the husband’s brother’s wife. Her two sons are lawyers as well, one practices at the Supreme Court, while the other practices at the high court. One of her daughters-in-law is also a lawyer.

Senior advocate Mahalakshmi Pavani also points out that every profession has family members carrying the legacy forward in the same profession.

“I don’t see anything wrong or surprising with the fact that a lawyer or a judge’s son would like to me a lawyer and probably a judge in the future,” she told ThePrint, adding, “It’s for the person carrying the legacy forward to prove his mettle and merit in the profession.”

Pavani feels that lineage makes a generational lawyer’s task tougher.

“There is always a comparison with the father or the grandfather, or father-in-law in my case. So it is a herculean task to live with this, and try to do better than what their predecessors had done,”says Pavani, whose father-in-law was senior advocate P.P. Rao.

Pavani, however, does see a need for transparency and accountability within the judiciary. “Judges are not above the law…Our country has the only system in the world where judges appoint each other, and it’s a closed-door affair.”

While the phrase “uncle judges” may often be used informally in corridors of courts across the country, the Law Commission of India’s 230th report on judicial reforms had formally used the phrase for the first time.

The report claimed that there were often complaints about “uncle judges”, which among other things, is a phenomenon where relatives or close associates of judges practice law in the same court. The commission had then recommended that judges whose kith and kin are practising in a high court should not be posted in the same high court. This, it said, will eliminate “uncle judges”.

Earlier this year, it was reported that there were discussions about discouraging high court Collegiums from recommending judgeship for lawyers or judicial officers whose parents or close relatives were/are judges of the Supreme Court or high courts.

Reacting to the reports, Congress leader and senior advocate Abhishek Singhvi had lauded the move on social media platform X. “Reality of judicial appointments is much murkier and much much more non objective than originally conceived. Mutual Back scratching, uncle judges, family lineages etc demoralise others and bring disrepute to institution,” he wrote.

He added that this was easier said than done, and that “till now we are unable to even ban lawyer relatives practicing in the same HC as judge relatives”.

It is unclear if there has been any further discussion on this idea.

A path to reform

Justice Banerjee has several suggestions for reforming the current judicial system.

He points towards the necessity of a “judicial management system” to improve the efficacy of the courts. “Good judges do not mean good managers. So we need a system to take this burden off the judges,” he says.

He also recommends the establishment of a “judicial audit committee” manned by auditors who should report to the chief justices of the high courts and the CJI. “All financial dealings and assets of all judges should be available, including incremental changes,” he suggests.

Justice Banerjee also has proposals for improving the current system of Collegium appointments: when names are recommended, whether it is for the high court or the Supreme Court, it’s the entire list which should be considered by the government.

“It shouldn’t be that one or two names are picked and the other names not considered or deferred. The list should be returned with inputs by the government,” he added.

However, Justice Banerjee warns against a “knee-jerk reaction without a concrete, thorough investigation,” when it comes to reforming judicial appointments.

‘Inbreeding’

Apart from familial connections, experts have often pointed to a lack of diversity and representation within the judiciary.

Speaking to ThePrint, Justice Chandru referred to a response in the ongoing budget session of Parliament by the Ministry of Law and Justice in Parliament, stating that 551 out of 715 or 77 percent of all high court judges appointed since 2018 were from ‘upper castes’.

The response, by Law Minister Arjun Kumar Meghwal, also said that out of 715 high court judges, merely 22 belong to Scheduled Caste (SC) category, 89 belong to OBC category, and 37 belong to Minorities.

“This is a clear reflection of inbreeding and upper caste domination in the selection of judges,” Chandru asserts.

Rohin Bhatt, a lawyer practicing in Delhi, also adds that various factors such as class, caste, gender and sexuality influences who gets to be on the bench.

He calls it “shocking” that the Supreme Court is currently functioning with merely two women judges. Bhatt points out that former Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud appointed 18 judges to the Supreme Court, but none of them was a woman.

“Similarly, no openly queer judge has ever made it to the bench of our constitutional courts. The ratio of judges from SC/ST/OBC communities continue to remain abysmal,” he says, adding, “When marginalized groups are not represented in the legal system, they cannot in good faith be expected to have faith in it.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: 8 of 25 high courts have only 1 woman judge. Data shows poor representation in higher judiciary