Chandigarh: The Haryana Assembly Friday invoked the landmark 1964 case of Keshav Singh versus UP Assembly Speaker, while passing a resolution to ignore a Punjab & Haryana High Court notice issued to Speaker Gian Chand Gupta on a petition filed by Indian National Lok Dal (INLD) MLA Abhay Singh Chautala.

The Keshav Singh case had in 1964 provoked a constitutional crisis and first defined the separation of powers between the judiciary and legislature – two key arms of democracy in India.

The present matter arose in the Haryana Assembly after Chautala filed a plea in court last month against his two-day suspension from the House by Speaker Gupta.

On February 21, during the ongoing budget session, Gupta suspended Chautala for alleged unparliamentary behaviour. A peeved Chautala moved the HC the next day, seeking quashing of the suspension order. He termed Gupta’s action as contrary to the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Haryana Assembly.

Taking up Chautala’s plea, the HC on February 23 sought a response from the Haryana Vidhan Sabha secretariat.

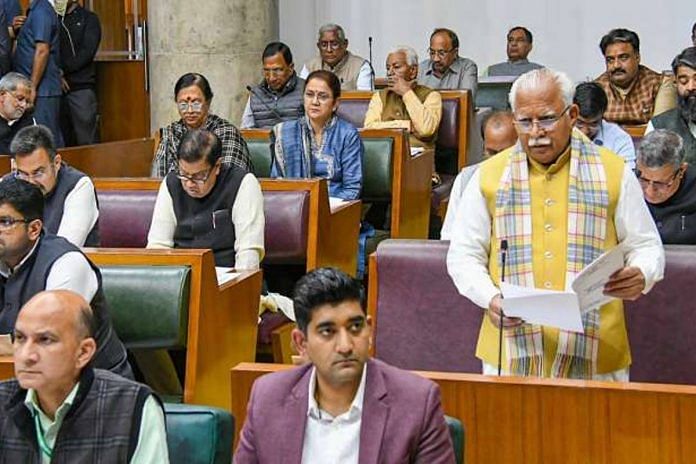

On Friday, during the course of proceedings of the assembly, Haryana parliamentary affairs minister Kanwar Pal moved a resolution – a copy of which ThePrint has accessed – which stated that the notice received by the secretariat from the HC was contrary to the provisions of Article 212 of the Constitution and “an act of interference” with the internal proceedings of the House.

Article 212 states that the validity of any proceedings in the Legislature of a State shall not be called in question on the ground of any alleged irregularity of procedure.

“Going by the verdicts of the Supreme Court and various high courts from time to time, and also as per the provisions of Article 212 of the Constitution, the courts can’t look into the proceedings of the legislatures,” stated the resolution, proposing that the HC’s notice “should be ignored and a reply should not be submitted”.

Passing the resolution with voice vote, Speaker Gupta quoted some judgments of the Supreme Court, including the Keshav Singh case.

Gupta pointed out that in the Keshav Singh case, the Supreme Court had said under a presidential reference that Article 212 (1) of the Constitution “lays down that the validity of any proceedings in the Legislature of a State shall not be called in question on the ground of any alleged irregularity of procedure”.

He added that the SC had also ruled that Article 212 (2) “confers immunity on the officers and members of the Legislature in whom powers are vested by or under the Constitution for regulating procedure or the conduct of business, or for maintaining order, in the Legislature from being subject to the jurisdiction of any court in respect of the exercise by him of those powers”.

What was the Keshav Singh case that students of law in various universities across India study today, and how did it underline the separation of powers under the Constitution? ThePrint explains.

Also read: Haryana MLAs will undergo training to understand ‘nitty-gritty’ of Budget for ‘constructive debate’

What happened in 1964

In his book titled The Cases That India Forgot, author Chintan Chandrachud discusses the Keshav Singh case as the first of the 10 he takes up.

In a 20-page discussion on the case, Chandrachud says: “Who would have thought that a pamphlet distributed by a local politician would paralyse administrative machinery, strain relations between state institutions and provoke a constitutional crisis? This is precisely what happened in 1964. It took the collective efforts of several Supreme Court judges, high court judges, MPs and MLAs, and ultimately the Prime Minister and the Chief Justice of India to restore equilibrium.”

A resident of Gorakhpur in UP, Keshav Singh was a worker of the Socialist Party. He came into the limelight after he, along with his colleagues, published and distributed a pamphlet titled ‘Exposing the Misdeeds of Narsingh Narain Pandey’, a Congress MLA, accusing him of corruption.

Pandey complained to then UP Assembly Speaker Madan Mohan Varma that the pamphlet amounted to breach of privilege of the rights and immunities enjoyed by the assembly and its members

Singh and his companions were summoned to the assembly to receive a reprimand for their act. While his two companions complied with the notice and appeared before the assembly on 19 February, 1964, Singh failed to do so citing lack of funds to travel from Gorakhpur to Lucknow, narrates Chandrachud in his book.

On the orders of the UP Assembly, Singh was arrested and produced before the House on 14 March, 1964.

At the assembly, despite the Speaker asking Singh to confirm his name repeatedly, he kept standing with his back to the Chair and responded with silence to the questions posed to him.

“The Speaker then brought to the attention of the assembly a letter that would cause further consternation among Congress MLAs. Singh had written a letter to the Speaker protesting against the reprimand, confirming that the statements in the pamphlet (he had distributed) were accurate, and condemning the warrant for his arrest as ‘Nadirshahi’ (tyrannical),” writes Chandrachud.

Then UP chief minister Sucheta Kripalani subsequently moved a resolution in the state assembly proposing an imprisonment of seven days for Singh. The resolution was passed and Singh was sent to jail.

However, a day before he was to be released, an advocate filed a habeas corpus petition before the Allahabad High Court on Singh’s behalf, seeking his immediate release. The plea argued that the detention was illegal, and that the assembly didn’t have the power to send him to jail.

A high court bench of Justice Nasirullah Beg and Justice GD Sehgal ordered that Singh be released on bail subject to certain conditions, including that he will attend the court on future hearings of the case.

Considering the HC order as contrary to the separation of powers, the UP Assembly “passed a resolution with an overwhelming majority that Singh shall remain in prison and be brought back to the Assembly to answer for the petition filed in the high court”.

Speaker Verma also held that the high court’s order undermined the assembly’s exclusive authority to address a breach of its own privileges.

The resolution further ordered that Singh’s advocate B Solomon, and Justices Beg and Sehgal, who had “breached the privileges of the assembly”, be brought in custody before the Assembly to answer for their “indiscretions”.

Thus, a matter between a local leader and an MLA snowballed into a confrontation between two constitutional institutions.

The SC steps in

Commenting on the clash, Chandrachud writes: “If the judges agreed to appear before the assembly, the episode would risk undermining the independence of the judiciary. On the other hand, if they appeared and offered a robust defence, the assembly might be left with no choice but to refrain from further action, lest it be criticised for persecuting well-intentioned judges”.

The two judges filed a petition before the Allahabad High Court arguing that the resolution passed by the UP Assembly was in violation of Article 211 of the Constitution, which states that no discussion shall take place in the Legislature of a State with respect to the conduct of any judge of the Supreme Court or of a High Court in the discharge of his duties.

A bench of 28 judges of the high court (all except Justices Beg and Sehgal), the largest bench of any high court or the Supreme Court to date, heard the petition of the two judges and restrained the government from securing the execution of arrest warrants against them.

The chain of event led to intervention of the central government and it was decided that a presidential reference be made so that the Supreme Court could pass an order to end the impasse. The stage was set for one of the most captivating legal battles.

In 1965, the Supreme Court in its ruling in the case interpreted certain important provisions of the Constitution.

One was Article 194 (3), which states that the powers, privileges and immunities of the state legislature should be defined by law. However, until they were defined by law, they would be the same as of the House of Commons of the UK.

Before the court was also Singh’s argument that parliamentary privileges were being exercised in violation of right to personal liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution. Singh contended that in case of a conflict between a constitutional right and parliamentary privilege, the former shall prevail.

Another provision of the Constitution the Supreme Court interpreted was Article 211. It was argued on behalf of the two judges that the assembly resolution requiring their attendance to explain their conduct was in violation of Article 211.

Delivering its verdict, the Supreme Court held that it was within the authority of the high court to consider Singh’s petition and release him on bail until it arrived at a decision.

At the same time, the Supreme Court held that “it is not denied… that the House of Commons has the power to commit for its contempt. This power of commitment has been described in England as the ‘keystone of parliamentary privilege’. In our opinion, both upon authority and upon a consideration of the relevant provisions of the Constitution, it must be held that the Legislative Assembly has, by virtue of Article 194(3), the same power to commit for its contempt as the House of Commons has”.

Deciding Singh’s fate, the Supreme Court held that since the assembly had the power to imprison for contempt, the court will not go into the proprietary and legality of the proceedings in the UP Assembly.

Singh was thus ordered back to prison to serve the remaining one day of his sentence.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Why Haryana Opposition is demanding local development fund for MLAs — ‘officials reject projects’