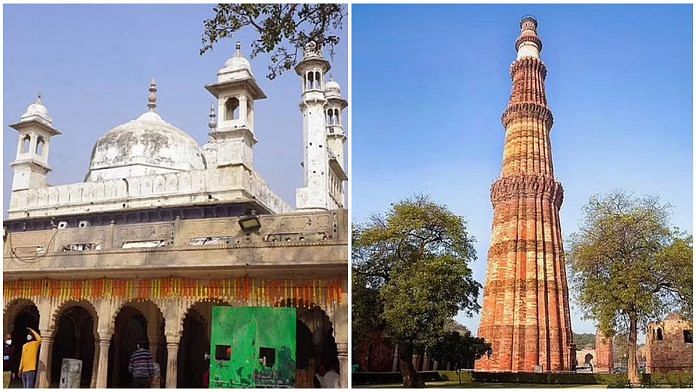

New Delhi: Earlier this week, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) told a Delhi court there could be no right of worship in a centrally protected monument. The court was hearing a petition that wanted Hindu and Jain deities restored at the Qutub Minar, one of the national capital’s most iconic monuments.

In its affidavit, the ASI relied on the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958.

The Act has been in the news lately not only in connection with the Qutub Minar case, but also in connection with a title suit involving the Gyanvapi mosque that a Varanasi court is currently hearing.

On the one hand, the Hindu Sena — in an intervention application in the Gyanvapi case in the Supreme Court — used the law to counter the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which seeks to preserve the “religious character” of a place of worship as it existed on 15 August 1947.

On the other, the ASI has relied on the Act in the Qutub Minar case to claim that the mosque’s character was frozen after it came under the protection of the law.

The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, was introduced as a consolidated law to deal with ancient monuments of national importance as well as archaeological sites and remains that have not been declared to be of national importance.

It stems from an over-a-century-long quest to safeguard India’s architectural and historical legacy.

Also Read: For BJP, Gyanvapi is like Babri. It’ll swing elections but take India back to a dark past

161-year-long quest

The attempts to survey monuments in India began in 1784, leading to the formation of the ASI 161 years ago in 1861.

The first prominent legal reform came in the form of the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act, 1904, which was enacted for the preservation of ancient monuments and objects of archaeological, historical or artistic interest. It allowed the central government to declare an ancient monument protected.

It was under this law that the Qutub complex was notified as a protected monument on 16 January 1914. According to the notification, a copy of which was filed in the Delhi court, this included the entire “Qutb archaeological area… including the mosque”.

After Independence, the Parliament passed the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Declaration of National Importance) Act, 1951, which declared certain monuments as being those of national importance.

However, it was then noticed that since this law only dealt with monuments of national importance, the position on the preservation of other monuments was unclear since no parliamentary law spoke about them at the time.

Cue the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act, 1958.

What the law says

According to the 1958 law, any structure, monument, cave, rock sculpture, inscription or monolith of historical, archaeological or artistic interest that has been in existence for at least 100 years is an “ancient monument”.

It allows the central government to declare any ancient monument as one of “national importance”.

All monuments declared protected under the 1904 Act — like the Qutub Minar — come under the ambit of the 1958 law.

Section 16 of the law says that any protected monument that is a place of worship or shrine cannot be used for any purpose inconsistent with its character.

Section 20A of the 1958 Act makes the area “beginning at the limit of the protected area or the protected monument… and extending to a distance of one hundred metres in all directions” a prohibited area.

The only authority that can carry out any construction is an archaeological officer. This power is usually utilised to construct public amenities at the monuments, such as museums, ticket stalls, and toilets.

Section 20B says that an area of 200 metres beyond the prohibited zone — that is, from 100 to 300 metres — is a ‘regulated’ zone. Permission is required to undertake any sort of construction activity in regulated areas.

Through an amendment in 2010, the Act also provides for the constitution of the National Monuments Authority, which is tasked with implementing these provisions on prohibited and regulated areas of centrally protected monuments.

The ASI, which comes under the Department of Culture, is mandated by the 1958 law to regulate “all archaeological activities in the country” in line with the provisions of the Act.

It conducts archaeological research and is tasked with the protection of the cultural heritage of India, and maintenance of ancient monuments and archaeological sites and remains of national importance. It is also tasked with the security of monuments and keeping out encroachments.

Also Read: Lakshmi, Sita, Rekha, Manju, Rakhi — meet the 5 women at the centre of Gyanvapi petition

ASI’s defence, Hindu Sena’s arsenal

The ASI has cited sections 20A and 20B of the 1958 law in Delhi’s Saket court, which is hearing an appeal challenging a December 2021 order that had rejected a civil suit seeking restoration of Hindu and Jain deities in the Qutub Minar complex.

The ASI affidavit in the court reads: “The intention of the statute is clear that the monument should be protected and preserved in its original condition for posterity. Therefore, changing and altering of the existing structure would be a clear violation of the AMASR Act, 1958, and thus should not be allowed.”

This law cropped up in the Gyanvapi case when the mosque’s management committee approached the Supreme Court against orders directing a survey of the mosque. The 1958 law was cited by the president of the Hindu Sena, a Hindutva outfit, in the Supreme Court when they claimed an exemption from the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991.

The mosque management committee relied on the 1991 Act while challenging the validity of the survey because the law prohibits conversion of places of worship — like churches, mosques and temples — from their nature at the time of Independence.

In its response, the Hindu Sena referred to Section 4(3) of the 1991 Act, which says that the law won’t apply to “any place of worship… which is an ancient and historical monument or an archaeological site or remains covered by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958”.

It has been argued that since the erstwhile Kashi Vishwanath Temple and Shringar Gauri Temple within the Gyanvapi mosque complex fall under the 1958 law, the 1991 law would not apply.

What have courts said

In 2007, the Himachal Pradesh High Court considered a similar question that involved a claim by a few Christians asking the court to allow them to worship at an ancient church, the ‘All Saints Church’, in Shimla.

The church is located within the premises of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, previously known as Vice Regal Lodge.

The lodge was declared a protected ancient monument in May 1997.

In its verdict, the high court interpreted the exception in Section 4(3) to mean that the 1991 law would not stop the declaration of any structure as an ancient and historical monument.

It also noted that the church in question was not in use after Independence, and ruled that “once a monument has been declared to be a protected monument and is owned by the government, then the congregation cannot insist that the place of worship must actually and actively be used for religious services”.

Civil judge Neha Sharma — who first rejected a suit for restoration of deities in the Qutub complex in December last year — had also taken note of the exception under Section 4(3) of the 1991 Act.

However, she ruled that “such ancient and historical monument cannot be used for some purpose which runs counter to its nature as a religious place of worship, but it can always be used for some other purpose which is not inconsistent with its religious character”.

“In my considered opinion, once a monument has been declared to be a protected monument and is owned by the government, then the plaintiffs cannot insist that the place of worship must actually and actively be used for religious services,” the judge said.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: ‘Lotus, sheshnaag, vermillion-hued idols’: What ‘survey report’ says about Shringar Gauri site