New Delhi: From Ramlalla Virajman to Jain deity Tirthankar Lord Rishabh Dev and Bhagwan Shri Sankatmochan Mahadev Virajman, several deities have been involved in legal suits against masjid or dargah properties across the country.

In India, a deity is considered a “juristic person” or a legal entity that can own property and sue like a living person. While God – an abstract and omnipresent concept hasn’t been given a juristic identity – deities in Hindu law have been conferred personhood.

The concept of conferring legal personhood on Hindu idols was evolved by courts to ensure that the law adequately protected the properties endowed for religious purposes.

One of the most high-profile cases involving a deity was the Ayodhya dispute where Ramlalla Virajman, represented by his “next friend”, the late Deoki Nandan Agarwal, a former judge of Allahabad High Court, was one of the key parties.

In February 2008, Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) leader Triloki Nath Pandey took Agarwal’s place as the “next friend”.

A five-judge Supreme Court bench declared Ram Lalla a juristic person in a November 2019 judgement in the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid title dispute case.

“In the present case, the first plaintiff (Bhagwan Sri Ram Lalla Virajman) has been the object of worship for several hundred years and the underlying purpose of continued worship is apparent even absent any express dedication or trust…to ensure the legal protection of the underlying purpose and practically adjudicate upon the dispute, the legal personality of the first plaintiff is recognised,” the court had observed.

Most recently, a suit was filed by Bhagwan Shri Sankatmochan Mahadev Virajman, through his “next friend” and devotee, Vishnu Gupta, claiming that a Shivling lay beneath Ajmer’s dargah of Sufi Saint Moinuddin Chishti.

In response, a local Rajasthan court issued a notice to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the Union Ministry of Minority Affairs, and the Ajmer Dargah Committee last month.

How did the concept of assigning the status of a “legal person” to deities begin and what legal rights do these juridical persons have? ThePrint takes a deep dive into legal judgements over the years to explain how deities became legal entities in India.

The start of it all

Throughout history, several Indian and English judges have looked at the legal characteristics of Hindu idols and the properties associated with them in several judgments.

Before Independence, several such questions came before the courts with English judges applying Hindu law to religious endowments.

As far back as 1887, the Bombay High Court recognised the concept of an “artificial juridical person” under Hindu law in the Dakor Temple case. In other words, it conferred legal personality on a Hindu idol.

In the Ayodhya judgment, the Supreme Court explained that English judges began recognising the legal personality of Hindu idols due to two issues facing Indian courts.

One, the risk of maladministration by shebaits or managers, where land is endowed for religious worship, typically for an idol; and two, the threat of devotees being denied access to land designated for public worship.

But experts say even before courts recognised Hindu idols as legal personalities, India already had an age-old practice of individuals, merchants and rulers setting up religious endowments through which they dedicated properties to temples and idols.

Apart from Hindu deities, the Supreme Court has even held in 2000, the Guru Granth Sahib as a juristic person.

Since Sikhism doesn’t believe in idol worship, the court extended the principle to the Guru Granth Sahib, noting that according to the tenets of Sikhism, it is the Guru. The Guru Granth Sahib was, therefore, held to have juristic personality, and it was ruled that property can vest in it.

Not the God, but the purpose

In the Ayodhya judgment, the court clarified that granting legal personality to a Hindu idol did not mean conferring legal personality on divinity or the Supreme Being.

Referring to several past judgments, the court noted that the Supreme Being is omnipresent and divinity is universal and infinite.

Therefore, divinity cannot be granted the status of a legal entity, because it would not be possible to form its contours – it would be impossible to distinguish where one legal entity ends and the next begins.

At the same time, it noted that Hinduism provides physical manifestations of the Supreme Being through idols, which serve as identifiable forms for worship, making them eligible for legal recognition.

The court then explained that Hindus may create endowments for religious purposes, and there is public interest in protecting the “pious purpose” for which these properties were endowed.

“The law confers legal personality on this pious purpose… The idol as an embodiment of a pious or benevolent purpose is recognised by the law as a juristic entity,” it explained. In other words, it is an idol that acquires a legal personality and, consequently, legal rights.

The need to confer juristic personality stems from the need for legal certainty on who owns the endowed property. It also arises out of the need to protect an endower’s original intent and the future interests of devotees.

Who can file lawsuits

The idol as a juristic person has the title to the endowed property. However, the idol, of course, cannot enjoy possession of the property as a natural person would.

Therefore, the idol needs a human, or a shebait, to manage its properties, arrange for the performance of ceremonies associated with worship and take steps to protect the endowment by bringing lawsuits on behalf of the idol.

Ideally, only the shebait can bring a suit on behalf of the deity. However, the Supreme Court clarified in a 1966 case that in cases where the shebait is negligent or is the guilty party against whom the deity needs relief, worshippers or other interested parties in the religious endowment can file suits to protect trust properties.

“It is open, in such a case, to the deity to file a suit through some person as next friend for recovery of possession of the property improperly alienated or for other relief,” the court had observed in a 1966 judgment.

Deities fighting cases

Several suits have been filed on behalf of deities, laying claim to mosque or dargah properties across the country.

For instance, the original suit in the Gyanvapi case was filed in 1991 by devotees of the deity Swayambhu Lord Vishweshwar, who claimed that the mosque in Varanasi was built at the site after a temple was demolished in 1669 on the orders of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

They, therefore, demanded they should be allowed to “renovate and reconstruct their temple”. This suit remained pending for years because of an Allahabad High Court stay in August 1998.

However, in December last year, the high court ruled that this suit was not barred by the provisions of the Places of Worship Act. The case is currently being heard by the Varanasi Civil Judge’s court.

In another case in 2020, a suit was filed on behalf of the Jain deity, Tirthankar Lord Rishabh Dev, and Hindu deity Lord Vishnu, through their next of friends against the Quwwat-Ul-Islam Masjid in New Delhi’s Qutub Minar complex. The suit claimed that the mosque was built in place of a temple complex.

A Delhi civil court rejected the suit in December 2021, but an appeal against this decision is pending before an additional district judge in Delhi.

In the Ajmer Sharif case, the suit claimed that a “Shiva Linga lies beneath the underground passage to the cellar within the complex” of the dargah of Sufi Saint Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer.

The suit has been filed by Bhagwan Shri Sankatmochan Mahadev Virajman, through his “next friend” and devotee, Vishnu Gupta, who is the National President of Hindu Sena.

In the suit filed in a civil court in Ajmer earlier this year, Gupta has demanded that the deity, Bhagwan Shri Sankatmochan Mahadev Virajman, should be declared the owner of the property where Khwaja Dargah Sahib is located at Ajmer.

Among other things, he also sought direction to the Dargah committee and the Ministry of Minority Affairs, to remove the dargah structure allegedly built over the Mahadeva linga.

It also goes on to demand a direction to the Ministry of Minority Affairs to reconstruct the Bhagwan Shri Sankatmochan Mahadev Temple after removing the present structure and ensure arrangements for bhog, pooja and other rituals.

The alternative

However, it’s not just suits filed through “friends” of deities that are coming up before courts in such disputes. Purported devotees demanding the right to worship alleged idols within mosque complexes are also filing suits.

For instance, while the original 1991 suit in the Gyanvapi case remained pending because of the high court stay, in August 2021 five women filed a plea at a Varanasi civil court demanding praying rights inside the Gyanvapi Mosque compound.

They demanded permission to worship Maa Shringar Gauri, Lord Ganesh, Lord Hanuman and Nandi idols allegedly located inside the mosque, within an “old temple complex”. A district judge in Varanasi is currently hearing the suit.

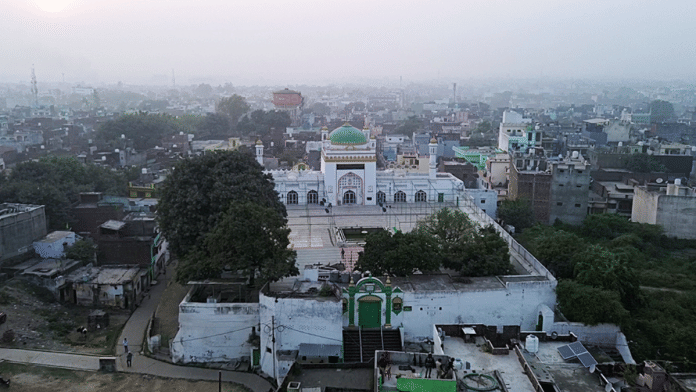

Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh’s Sambhal, eight people claiming to be Lord Shiva’s and Lord Vishnu’s devotees filed a petition saying that the temple previously stood at the site of the Mughal-era Shahi Jama Masjid.

The first is advocate Hari Shankar Jain. His son, Vishnu Shankar Jain, also represents the eight petitioners in the Sambhal case. He and his son are also involved in the Gyanvapi case.

The petitioners demanded access to the mosque, claiming that a centuries-old Hari Har Temple, dedicated to Lord Kalki, was being used unlawfully by the Jama Masjid Committee. Therefore, they demand “giving access to the members of the public within Shri Hari Har Temple/Jami Masjid”.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)