New Delhi: “The President has proclaimed Emergency. There is nothing to panic about.” With this declaration by former prime minister Indira Gandhi over the All India Radio, the Emergency was promulgated in India exactly 50 years ago, leading to the 21-month period that is often touted as the “blackest era” in India’s history.

Legal provisions within the Constitution as well as several laws, including the Defence of India Act, 1971, and the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971, were widely misused to curb dissent with an iron fist.

The idea was to clamp down on all the independent institutions of the country, including the media and the judiciary—leaving the citizens to the mercy of the all-powerful executive.

Journalist Coomi Kapoor’s book, ‘The Emergency: A Personal History’, mentions a plan to “lock up the high courts and cut off electricity connections to all newspapers”. While the latter did end up being enforced, the high courts were spared.

Lawyers and even judges protested, many from the legal community were jailed, and several high court judges passed orders against the government, at great personal cost.

According to senior advocate and former law minister Shanti Bhushan, as many as 21 judges were transferred during the Emergency without their consent. Other accounts note that 200 chambers of lawyers practising in Delhi’s Tis Hazari courts were demolished, without notice, and a warrant under the MISA was issued against advocate Ram Jethmalani, who was then the chairman of the Bar Council of India, following his speech criticising Indira and Sanjay Gandhi.

Jethmalani managed to get his arrest warrant stayed, left India for Canada, and sought political asylum in the US.

However, while several lawyers and high courts were attempting to stand firm, a major jolt to civil liberties came from the Supreme Court, in the infamous ADM Jabalpur verdict.

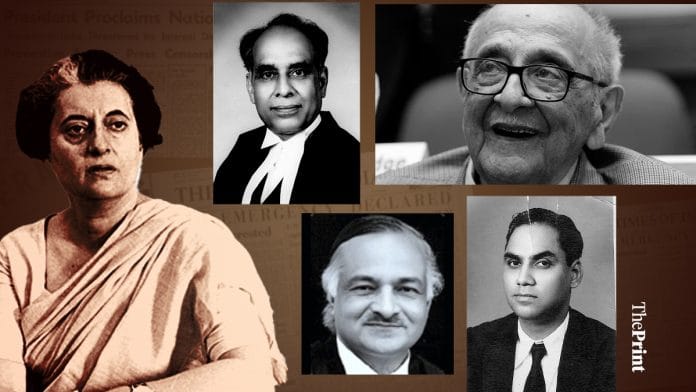

ThePrint looks at the members of the judiciary and the legal community who shaped the Emergency—either by standing tall against it, or by limiting the recourse available to ordinary citizens.

Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha

On 12 June 1975, Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha authored a judgment which changed the course of Indian history. He held Prime Minister Indira Gandhi guilty of two corrupt practices and declared her election to the Lok Sabha in 1971 “null and void”.

Bhushan wrote about the time that Justice Sinha was hearing the arguments in the case. He recalls that then Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court, Justice D.S. Mathur, visited Justice Sinha with his wife. Justice Mathur was related to Indira’s personal physician.

Justice Mathur then dropped a “subtle hint” to Justice Sinha— that his name had been considered for elevation to the Supreme Court and that he would get the appointment as soon as he delivered the judgment in Gandhi’s case. Bhushan was representing Raj Narain, who had challenged Indira Gandhi’s election before the high court.

However, an unwavered Justice Sinha held Indira guilty of two corrupt practices and declared her election to the Lok Sabha “null and void”. Accordingly, it ruled that she stands disqualified for a period of six years.

Fali Nariman

Following the Allahabad high court verdict, an appeal for the Supreme Court was readied quickly. Then additional solicitor general (ASG) Fali S. Nariman recalls that the appeal was filed on the “most astrologically auspicious date”.

It was vacation judge at the time, Justice Krishna Iyer, who heard Indira’s stay application. However, the judge refused the PM’s request for an absolute stay on the high court judgment.

Instead, Justice Iyer granted a conditional stay, ruling that the Congress leader could participate in the proceedings as Prime Minister, but without a vote, and she could continue holding the PMO. This meant that she could not vote or participate in the proceedings as a Member of Parliament but could sign the Register of Attendance to save the seat.

A day after this order, on 25 June, the Emergency was announced.

The night of 26 June was the “most important turning point” in his professional career, Nariman wrote years later. He had decided to resign from his post, with a one-line letter of resignation.

The judges who stood tall

With the imposition of the Emergency, Article 359 of the Constitution at the time allowed the government to suspend the right to approach courts for enforcement of all fundamental rights. Accordingly, two days after the Emergency, an order was issued by the President, suspending the rights of the citizens to approach the courts for enforcement of their fundamental rights under Article 21 (right to life and personal liberty), Article 14 (equality before law) and Article 22 (protection against arrest and detention).

A combination of widespread arrests and this order meant that citizens could no longer take legal action against illegal detentions.

However, the high court stepped up despite such orders and provisions in place. At least nine high courts—Allahabad, Andhra Pradesh, Bombay, Delhi, Karnataka, Madras, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana, and Rajasthan—allowed several detainees to file habeas corpus petitions before the courts.

Many of these judges faced repercussions owing to their orders.

For instance, Justice Rajendra Nath Aggarwal, then an additional judge of the Delhi High Court, was not made a permanent judge and was reverted to the post of district and sessions judge instead. This was despite the fact that he served in the high court for four years, and that the then chief justice of the high court had recommended that he was “an asset to the high court”.

This was after he ruled against the government in a habeas petition filed by Bharti Nayyar, wife of The Indian Express journalist Kuldip Nayar. A bench comprising Justices S. Rangarajan and Aggarwal had quashed his arrest under the MISA, criticising the conduct of the government. Justice Rangarajan was transferred to the Gauhati High Court.

Even the Shah Commission looked into Justice Aggarwal’s case, observing that the order against Justice Aggarwal was “prima facie in the nature of an order of punishment for participating in the hearing in Kuldip Nayar’s case and passing an order which tarnished the image of the Government in public eye”. This, the panel formed to inquire into all the excesses committed in the Emergency said, was “a case of misuse of authority and abuse of power”.

Transfers, protests

Several other judges were also transferred without their consent during the Emergency, after they passed orders against detentions.

For instance, Justice U.R. Lalit of the Bombay High Court, who had also ordered the release of a few detainees, was not confirmed as a permanent judge, despite recommendations from the chief justice of the high court, the chief minister of Maharashtra, the CJI, and law minister H.R. Gokhale.

Justices D.M. Chandrashekar and M. Sadananda Swamy, who quashed the detention of various political leaders including BJP’s A.B. Vajpayee and L.K. Advani, were transferred as well. Justice Swamy was sent to the Gauhati HC, while Justice Chandrashekhar was transferred to the Allahabad HC.

Meanwhile, the legal community was up in arms against the steps being taken by the government.

In October 1975, a conference seeking immediate restoration of the liberties of citizens was preceded over by a former Chief Justice of India, Justice J.C.Shah, in Ahmedabad. When the Maharashtra government banned any public meeting where the Emergency could be discussed or even referred to, Justice N.P. Nathwani took the matter to the Bombay High Court.

A battery of 157 lawyers, led by the renowned lawyer N.A.Palkhivala, appeared for the petitions and got the ban quashed, only for the high court judgment to be stayed by the Supreme Court soon after.

The ADM Jabalpur bench

However, it was a five judge bench of the Supreme Court on 28 April 1976 that left one of the deepest marks on the judiciary as well as the country during the Emergency.

The case, titled Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla, was heard by Chief Justice of India A.N.Ray, and Justices H.R.Khanna, M.H. Beg, Y.V. Chandrachud and P.N. Bhagwati over a period of 37 working days, from December 1975 to February 1976.

The majority verdict ruled in favour of the government, asserting that nobody could ask for any relief from a court as the fundamental right to personal liberty had been suspended—not even if the order of detention was unauthorised, or was mala fide, or a wrong person was detained.

Justice Khanna was the lone dissenter, and has since been hailed for standing up to the all-powerful executive at the time. His dissent, however, cost him chief justiceship. Despite being the most senior Supreme Court judge, he was superseded by Justice Beg as Chief Justice in 1977. Justice Khanna resigned the same day.

But Justice Khanna’s dissent made international headlines. “If India ever finds its way back to the freedom and democracy that were proud hallmarks of its first eighteen years as an independent nation, someone will surely erect a monument to Justice H.R. Khanna of the Supreme Court,” an article published in The New York Times on 30 April 1976 said.

It was only in 2017 that Justice D.Y.Chandrachud overruled this judgment in the right to privacy, or the Justice K.S.Puttaswamy verdict.

“…when histories of nations are written and critiqued, there are judicial decisions at the forefront of liberty. Yet others have to be consigned to the archives, reflective of what was, but should never have been,” Justice Chandrachud had said in a majority opinion.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: ‘India will never accept dictatorship’—Amit Shah on 50th anniversary of ‘dark chapter’ of Emergency