New Delhi: Coronavirus is giving India’s politicians the jitters. The virus is likely to stay longer than anticipated, threatening to change the rules of what has traditionally been a contact sport — politics.

Social distancing norms would mean no mega rallies, no town hall or village square meetings, and not even ‘chai pe charcha’— at least, not on the scale they used to be. Protests and demonstrations would be construed as a public health hazard. What would happen to politicians then? The question is giving sleepless nights to many.

“It’s a big crisis for us. Chunav maathe par hai. Pata hi nahin chalta kaise move karein (Elections are round the corner. Don’t know how to move around),” Lalan Paswan, an MLA from Bihar’s Chenari constituency, told ThePrint. He has got projects worth Rs 1,000 crore sanctioned for his constituency, but is unable to lay their foundation stones due to the lockdown.

“Etna bura samay to kabhi aayaa hi nahin… ab lagta hai TV, radio par hi prachar karna hoga (Never encountered such bad times. Seems we will have to campaign through TV and radio only),” said three-term BJP MLA from Barh, Gyanendra Singh Gyanu.

Bihar assembly elections are slated in October-November.

However, it’s not just politicians from poll-bound states who are worried. Their counterparts in other states also dread the prospects of having to live with the virus and do politics, too.

What if a vaccine is never found and the virus never goes away as British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the World Health Organization have ominously warned!

Indian politicians are not so pessimistic but are thinking aloud: How does one do politics in times of coronavirus when there is restricted space for physical interactions with voters? Who will be the gainers and the losers if the virus is here to stay — the ruling or the opposition parties?

Also read: Coronavirus has brought India’s almighty Centre back, and Modi’s unlikely to give up control

Change-or-perish dilemma for politicians

India’s politicians have come a long way since the days of the Sanjeev Kumar and Suchitra Sen-starrer Aandhi (1975) when people would greet them with sarcasm for turning up after five years to seek votes: Salaam kijiye/ aali janaab aaye hain/ ye paanch saalon ka dene/ hisaab aaye hain.

Twenty first century politicians are much more accessible and responsive to voters. Their visits to their constituencies are more frequent. They use Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp to communicate with voters, but meetings and rallies have continued to define their politics.

Those days are over when you had to fill in buses with people and take them to big rallies to make them hear what they already knew, said a veteran Congress politician, adding that those rallies were “already a farce, a mere show of strength”. But politics can’t also be done only digitally, he added.

His younger colleague, Deepender Hooda, believes in “looking in the eye” of voters.

“There are two types of horses — baaraat ka ghoda aur jung ka ghoda (horses used in wedding ceremonies and those used in wars). A true politician has to be among the people to fight for their cause. He has to be a jung ka ghoda,” he said.

“You can call me old-school but I am a touch-and-feel politician. Social media is fine but usse baat nahin banti (that’s not enough),” said Hooda, a four-term MP. He is, however, no ignoramus when it comes to social media. He has 2,65,000 followers on Twitter and a million followers on Facebook. But he sees no substitute for “touch-and-feel” politics.

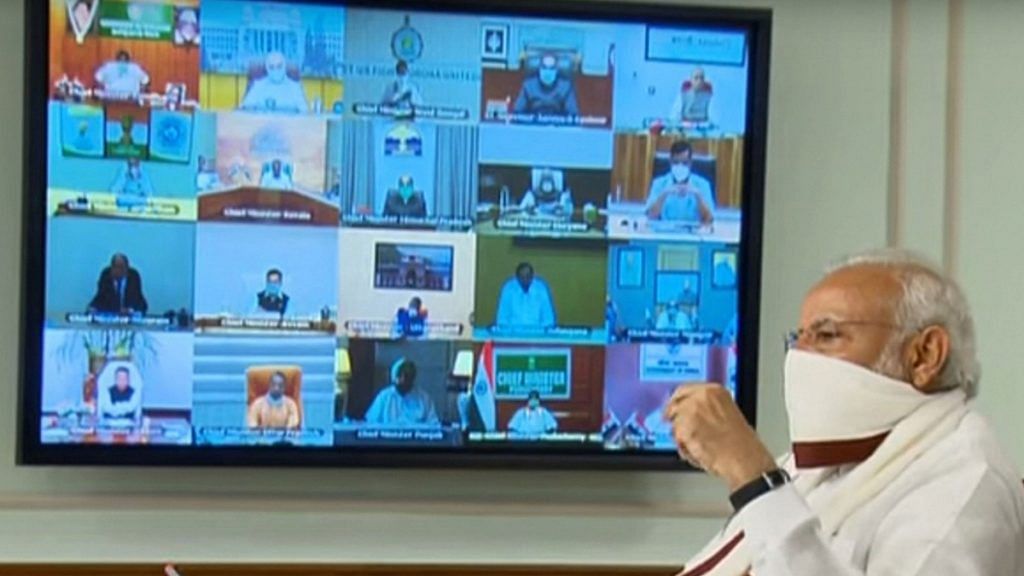

Although Prime Minister Narendra Modi inspired many politicians to take to Twitter and Facebook, they have treated it as a force multiplier, at best.

The social media’s reach has expanded exponentially in India: 40 crore users of WhatsApp, over 28 crore of Facebook, 9 crore of Instagram, 20 crore of Tik Tok and 26 crore of YouTube. There is no official data for active Twitter users in India. Statista, a business data platform, pegs it at 13.15 million but it raises many questions, given that Modi has 57 million Twitter followers and even Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has 14 million.

Lalan Paswan, who has contested six elections, sums up the dilemma of politicians: “PM ka video hum ghumayenge; gaon mein gaay-bakri charane wala bhi dekhta hain. Lekin jo sabha mein taali bajti hai, waisa toh nahin hoga (Will circulate PM’s video that is watched by cow and goat-grazers. But the claps that one hears at meetings will not happen).”

Uncertain about how long coronavirus would restrict their movements, many politicians are already sprucing up their communication strategy.

Former Union minister Jitin Prasada, for instance, has started ‘Kaise Hain Aap’, a daily video conference on Zoom with party workers across Uttar Pradesh. “You will be caught napping if you don’t prepare for digital communication. Social distancing is here to stay. You must ramp up your social media strategy,” said Prasada.

BJP MP from Mysuru Pratap Simha does not see any existential crisis for politicians even if coronavirus stays for a few years.

“Even during the lockdown period, Modiji is using both the social media and the traditional media to convey his message to the people. You saw how the entire country responded to his call for, say, ‘Janata Curfew’ or social distancing. You don’t need a gathering to convey your message. Everybody has got a smartphone today,” said the Mysuru MP.

Political scientist Suhas Palshikar thinks the pandemic may “narrow the space of politics.”

“Real politics will probably not happen. It may narrow the contours of what we know as politics. Mobilisation of people, say, against labour laws, will become impossible. The very space for coming together would be denied and courts would construct it as a legitimate denial. Our culture of politics will fundamentally change for the worse for lack of actual democratic space,” said Palshikar.

Also read: Covid hasn’t gone viral in India yet, but some in the world & at home can’t accept the truth

Will coronavirus favour ruling parties?

The ruling party at the Centre and those in states are facing the brunt of criticism for mismanaging the Covid-19 crisis, with visuals of migrant workers walking back home and dying on rail tracks and roads flooding the social and traditional media, and millions of people staring at livelihood questions amid an economic slump. But, these images, believe many politicians across party lines, will fade away sooner than later and the narratives of governments will gain prevalence.

Chandrika Rai, a veteran Bihar legislator and Lalu Prasad Yadav’s samdhi, said: “Opposition parties will be the real losers as they are cut off from the people. Tejashwi (Yadav) was sitting in Delhi when (Chief Minister) Nitish Kumar was firefighting here. People see how the Prime Minister and the chief minister are working hard to deliver them food and medical facilities, and revive the economy. Where are the opposition politicians?”

Rai quit Yadav’s Rashtriya Janata Dal recently.

Senior Congress leader and MP Manish Tewari, however, disagreed, saying that when these migrants share their experiences back home, people will be alienated from the BJP.

“As per the 2011 census, there were 11 crore inter-district and four crore inter-state migrants. The numbers have only gone up in the past decade. They can’t forget how the government treated them. There are and will be massive job losses, too,” he added.

In the event of the pandemic affecting more and more people in the coming months and years, and the stuttering economy causing more job losses, the ruling parties may be on the back foot. But their advantage, even opposition politicians concede, lies in their ability to control the narrative. The Prime Minister and the chief ministers’ advantage over their political rivals in terms of their access to communication tools and platforms, and their ability to touch people’s lives through welfare measures is a given.

Suhas Palshikar agreed. “It is true that the opposition has a big disadvantage, especially smaller parties that are not in power.”

But the “brand equity” of opposition leaders will also matter, argued Hooda.

“This advantage of the ruling parties will not work where you have strong opposition leaders. If you have a non-descript BJP CM and a credible opposition face, people will opt for the latter. In Haryana, for instance, people are very unhappy with (Manohar Lal) Khattar government. The only alternative they will find is Hoodaji (former chief minister Bhupinder Singh Hooda),” he said.

Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Jagan Mohan Reddy or his Telangana counterpart, K. Chandrasekhar Rao, for instance, do not have any credible opposition in their states. A prolonged period of social distancing and the resultant absence of public movements or agitations by opposition parties are likely to consolidate the position of these CMs and their parties.

Also read: Besides Covid, Shivraj’s fighting dissent — from Congress defectors & BJP leaders they beat

Blow to wannabe leaders

While seasoned politicians are still weighing their options, coronavirus may have delivered a big blow to aspiring and emerging politicians.

Chandrasekhar Azad of the Bhim Army, for instance, was emerging as a threat to Bahujan Samaj Party’s Mayawati, mobilising Dalits across the country through rallies and agitation programmes in sharp contrast to her Twitter-driven politics.

He has virtually disappeared from the headlines even though he is active on Twitter and Facebook. Many others such as Kanhaiya Kumar and Mukesh Sahni of Bihar, Jignesh Mevani and Alpesh Thakor of Gujarat, Pawan Kalyan of Andhra Pradesh, and Hanuman Beniwal of Rajasthan were similarly making their presence felt. They have since disappeared from headlines, with their images fading away from public memory.

Such is the impact of coronavirus that is known to target the weak and the disadvantaged — as much in health as in politics.

Also read: India is Asia’s new coronavirus hotspot as it overtakes China’s infection numbers