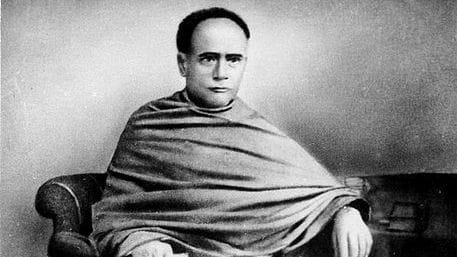

New Delhi: The vandalisation of Bengali polymath Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s statue in Kolkata Tuesday during violent clashes between BJP and Trinamool Congress supporters has brought the focus on the man who was one of the icons of Bengali Renaissance and a path-breaking social reformer.

The desecration of the statue has trampled upon Bengali pride and sentiment.

This is, however, not the first time that his statue has been vandalised. Nearly half a century ago, another statue of Vidyasagar was vandalised in Kolkata (then Calcutta) by Naxals, who beheaded the bust to protest against “the Bengali bhadralok’s idea of renaissance”. In those days, statues of other icons of Bengal Renaissance such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy were also smashed.

For Bengalis, Vidyasagar is a household name. Almost every school student in Bengal has learned to recite the Bengali alphabet in the sequence set by him in his book Borno Porichoy (Introduction to the Alphabet).

Due to his vast knowledge in several subjects, Ishwar Chandra had earned the title ‘Vidyasagar’. ThePrint recounts the man who revolutionised the education system in Bengal and also fought tooth and nail to usher in reforms to empower women in society.

Early life

Vidyasagar was born on 26 September 1820 at Birshingha village in Medinipur district of Bengal Presidency (now West Bengal) to Thakurdas Bandyopadhyay and Bhagavati Devi. Thakurdas was employed as a cook in a shop in Burrabazar, Calcutta, and had a meagre income of Rs 8 per month.

Vidyasagar spent his childhood in abject poverty. He would study under street lights as his parents could not afford gas light at home. He joined a local school at the age of five and studied there till the age of eight. As a child, he was always very curious about everything.

He got married at the young age of 14 to Dinamani Devi and the couple had a son named Narayan Chandra.

Also read: Amit Shah roadshow witnesses stone pelting & clashes in Kolkata

Education reforms

After his grandfather’s demise in 1826, Thakurdas decided to take Vidyasagar to Calcutta for further studies. He got numerous scholarships, and in 1839, he successfully cleared his law examination. Vidyasagar then joined Fort William College’s Sanskrit department at the age of only 21. Thereafter, in 1846, Vidyasagar joined the Sanskrit College as the assistant secretary.

In the first year of service, Vidyasagar recommended a number of changes in the syllabus and administration leading to a heated debate between him and college secretary Rasomoy Dutta. One of the issues on which Dutta and Vidyasagar debated was that Dutta wanted the college to remain open only for Brahmins, but Vidyasagar wanted it to be opened to all castes.

Following the altercation, he resigned and rejoined Fort William College as the head clerk.

In 1849, he, however, rejoined Sanskrit College as a professor of literature and introduced changes in the syllabus. He faced stiff opposition from the upper caste Hindu establishment for propagating the idea that men and women, regardless of their caste, should receive the best education, but he did not flinch.

He also advocated the teaching of science, mathematics and the philosophies of John Locke and David Hume instead of the ancient Hindu philosophy.

In 1851, he became the principal of Sanskrit College and was appointed as special inspector of various schools with additional charges in 1855. Between 1851 and 1855, Vidyasagar with many other reformers opened schools for women. He opened as many as 35 schools, using his own income, across Bengal and was successful in enrolling 1,300 students.

Champion of women rights

During those times, girls were not encouraged to go to school as people feared that it would interfere with household duties. Even the educated women were taught by their fathers or husbands at home.

Vidyasagar shattered these patriarchal mindsets by relentlessly lobbying for opening schools for girls. He even drew up a curriculum to not only educate girls but also enable them to be self-reliant by making them learn vocational courses like needlework.

He went door to door, requesting heads of families to allow their daughters to be enrolled in schools. He even initiated Nari Siksha Bhandar, a fund corpus to support his cause.

On 7 May 1849, Vidyasagar, with support from anglo-Indian lawyer John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune, established the first permanent girls’ school in India — Bethune School.

Widow remarriage

Vidyasagar fiercely advocated widow remarriage, but, unlike other reformers who sought to set up alternative societies, he made efforts to transform orthodox Hindu society “from within”.

In his times, remarriage of widows would occur very rarely, that too among progressive members of the Brahmo Samaj.

The deplorable custom of Kulin Brahmin polygamy allowed elderly men, usually on their deathbeds, to marry pre-pubescent girls. If those girls were widowed, they would be sent back to their parental homes and then subjected to cruel orthodoxy.

This would include very little food, rigid daily rituals of purity and cleanliness, hard domestic labour, and restricted freedom — to leave home or be seen by strangers.

Vidyasagar took the initiative to propose and push through the Widow Remarriage Act XV of 1856 in India, which was decreed on 26 July 1856.

His fight for widow remarriage did not just stop there. He even began finding suitable matches for child or adolescent widows, and got his son Narayan Chandra married to an adolescent widow in 1870 to set an example.

Reformed Bengali alphabets

Vidyasagar reconstructed the Bengali alphabets and reformed Bengali typography into 12 vowels and 40 consonants.

Vidyasagar also contributed significantly to Bengali and Sanskrit literature. He authored several books such as Betaal Panchabinsati (1847), Banglar Itihas (1848), Jeebancharit (1850), Bodhodoy (1851), Upakramonika (1851), Shakuntala (1855), Bidhaba Bibaha Bishayak Prostab (1855).

Upakramonika and Byakaran Koumudi interpreted complex notions of Sanskrit grammar in easy Bengali language. He also established the Sanskrit press with an aim to publish books at affordable prices so that common people could buy them.

He was also associated with prestigious publications such as Tattwabodhini Patrika, Somprakash, Sarbashubhankari Patrika and Hindu Patriot.

He passed away on 29 July 1891 in Kolkata at the age of 70. After his death, Rabindranath Tagore had said, “One wonders how God, in the process of producing forty million Bengalis, produced a man”.