New Delhi: It was as a result of the 1953 “coup” that Sheikh Abdullah was ousted, and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad took over as the second prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir. In her book Colonizing Kashmir: State-Building under Indian Occupation, 38-year-old Kashmiri author Hafsa Kanjwal documented how Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s regime was marked by censorship of literature, and bans on public gatherings and political speech.

Now, “life has come full circle” for Kanjwal. The very censorship she wrote about is now a reality for her. Her book is among 25 titles banned by the J&K home department at the orders of Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha. “It only emboldens me to keep writing. If they’re clamping down on literature, it must be saying something significant,” Kanjwal, an associate professor of history at Lafayette College in the US, tells ThePrint over the phone.

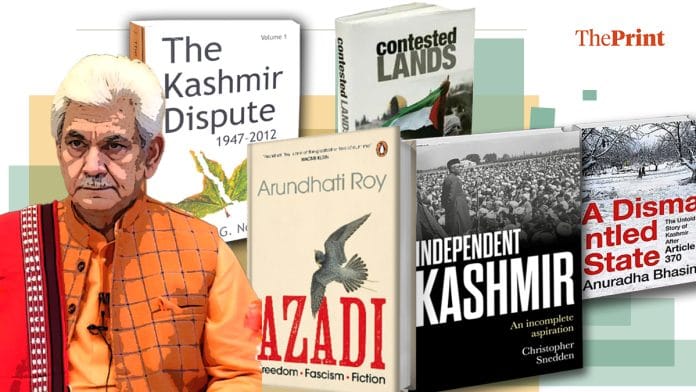

The J&K home department through a notification dated 5 August, 2025, imposed a blanket ban on 25 books written about Kashmir. This included author and activist Arundhati Roy’s Azadi (2020), journalist Anuradha Bhasin’s A Dismantled State (2022), constitutional expert late A.G. Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute (2013), and Australian political scientist Christopher Snedden’s Independent Kashmir (2021), among others.

The issue of the notification coincided with a book fair in Srinagar.

The notification issued by the principal secretary of the home department, Chandraker Bharti said the books propagate “secessionism”.

“…it has come to the notice of the Government, that certain literature propagates false narrative and secessionism in Jammu and Kashmir… This literature would deeply impact the psyche of youth by promoting (a) culture of grievance, victimhood and terrorist heroism,” read the notification.

Adding, “Some of the means by which this literature has contributed to the radicalization of youth in J&K include distortion of historical facts, glorification of terrorists, vilification of security forces, religious radicalization, promotion of alienation, pathway to violence and terrorism etc.”

Since the announcement, Jammu and Kashmir police have raided bookshops, followed by inspection of roadside book vendors and other establishments dealing in printed publications in Srinagar and across multiple locations in the Union Territory to confiscate the banned literature. Earlier this year, Srinagar district police declared it had seized “668 books” which it said “promoted the ideology of a banned organisation”.

While the police did not specify the banned organisation, National Conference MP Syed Aga Ruhullah Mehdi cited media reports to say that the police had seized literature by Abul Ala Maududi, the Islamic scholar who founded Jamaat-i-Islami. Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir, an offshoot of Jamaat-e-Islami, is banned in India under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Another offshoot, Jamaat-e-Islami Hind, was banned twice by the Government of India since its formation in 1948, but the Supreme Court revoked the ban on both occasions.

As for the J&K home department’s blanket ban on 25 books, including political commentaries and historical accounts, the move has drawn criticism not only from literati but also political and religious leaders.

Kashmir’s chief cleric Maulvi Omar Farooq wrote in a post on X on 7 August: “Banning books by scholars and reputed historians will not erase historical facts and the repertoire of lived memories of people of Kashmir.” The ban, he said, “exposes” the insecurities and limited understanding of those behind such “authoritarian” action.

‘Blend of Orwellian and Kafkaesque’

Kanjwal sees the ban as part of a broader, ongoing effort, which she says became particularly stark after 2019, to “suppress information and silence narratives” that challenge the official discourse. According to her, the earlier crackdown on Jamaat-e-Islami literature didn’t attract as much international attention, but inclusion of West-based Indian authors this time around may have prompted wider outrage.

Her own book, published by Stanford University Press and a recipient of the Bernard Cohn Book Prize awarded by the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), underwent rigorous academic review, she says.

Days after the ban, Kanjwal like several other authors whose books have been banned, is still contemplating the possible reasons behind the ban. She says it is clear that the aim was to “suppress information about Kashmir,” but she believes the move has backfired, drawing more attention to the very works it aimed to “suppress”.

Works by Kashmiri authors often offer alternative narratives, she points out, adding that the ban on mostly scholarly texts today could extend to poetry and fiction tomorrow.

Currently, Kanjwal is working on a people’s history of Kashmir aimed at younger readers, driven by the urgency to preserve and share Kashmiri narratives in a “climate of erasure”. She says growing censorship affirms the importance of writing about Kashmir, “especially for a generation growing up without access to political discourse or historical truth.”

The banned literature also includes works by noted scholars and writers such as Seema Kazi’s Between Democracy & Nation (2009), Ather Zia’s Resisting Disappearance (2019), and Essar Batool’s Do You Remember Kunan Poshpora (2016), all of which foreground Kashmiri lived experiences, especially of women.

Also banned are Al Jihad fil Islam by late Abul Ala Maududi and Mujahid ki Azan by Egyptian cleric late Hassan al-Banna, as well as scholarly works on international politics and law by Piotr Balcerowicz and Sumantra Bose. The banned titles include those published by both Indian and foreign publishers, from academic presses like Stanford University Press and Cambridge University Press to Penguin, HarperCollins, Routledge, and Zubaan.

Veteran journalist and author Anuradha Bhasin, whose book A Dismantled State is among those banned, calls the move “absolutely bizarre,” though not surprising.

“It is part of a pattern,” she tells ThePrint over the phone, pointing to a growing intolerance for independent thought, historical nuance, and rational voices, particularly on Kashmir. Bhasin argues that the banned works, many published by reputable academic houses, are rigorously vetted and based on deep research. “These are books that bring out the truth … nuanced, well-researched, and grounded in reality,” she says, rejecting the J&K home department’s claim that such literature glorifies terrorism or spreads false narratives.

Speaking of her own book, Bhasin says it was a product of over a year of journalistic reporting, interviews, and legal vetting. She sees the ban not only as an “attack” on literature but as part of a broader ecosystem of erasure, “from manipulated school textbooks to a complete silencing of media, civil society, and now, scholarship.”

“You’re going to produce a generation of youngsters who will have no knowledge, who will be reduced to non-thinking persons,” she says.

For Bhasin, the ban is particularly disheartening because the targeted books are foundational for academic engagement with Kashmir. “These are the books that professors recommend. Now, what are university students going to read?”

Political scientist Sumantra Bose, author of Kashmir at the Crossroads, tells ThePrint his goal was to identify “pathways to peace” and a future free of “fear and war” in Jammu and Kashmir. Dismissing defamatory slurs on his work, Bose calls the ban a “tragi-comic farce,” citing the police seizing books even at a state-sponsored festival. “This is a surreal dystopia … a real-life blend of the Orwellian and the Kafkaesque,” he says, adding that such bans are crude, futile in the digital age, and only draw global attention.

Calling it “criminalisation of scholars,” Bose notes both his banned books stem from years of field research in conflict zones. Drawing a parallel, he recalls how the British banned his granduncle Subhas Chandra Bose’s book The Indian Struggle in 1935. “Ninety years later, I follow in the footsteps of a legendary freedom fighter,” he says.

Ather Zia, anthropologist and author of Resisting Disappearance and co-editor of Resisting Occupation, another book that has been banned, says the move is not merely about silencing authors but about “criminalising history, memory, lived realities, and truth-telling.”

She, too, calls it part of a broader effort to suppress Kashmiri narratives that challenge the official discourse, particularly those grounded in Critical Kashmir Studies, a well-established academic sub-discipline shaped by Kashmiri scholars over the last two decades. Alongside her own works, she cites Colonizing Kashmir by Hafsa Kanjwal as among the globally taught, peer-reviewed books being targeted.

Despite the crackdown, Zia says Kashmiris “will continue to write, remember, and resist.”

ThePrint also reached Christopher Snedden and Essar Batool for a response but both declined to comment.

‘An exercise in not forgetting’

The ban by the administration has cast a chilling shadow over the region’s growing literary landscape, especially for young, emerging authors. Bhasin tells ThePrint that soon after the ban was announced, a young writer reached out to her, unsure of how to proceed in the current climate. Bhasin encouraged them to keep writing, but with caution.

“My advice would be to continue working, but to do it silently and wait for the opportune moment to write,” she says.

In the years following the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, as space for independent journalism in Jammu and Kashmir rapidly shrank under state pressure, many Kashmiris turned to literature as a safer medium of expression. Fiction, memoir, poetry, and personal narrative became tools to explore grief, memory, and resistance.

Writers like Mehak Jamal, Sadaf Wani, Zahid Rafiq, Farah Bashir, and Javed Arshi emerged as part of a new wave of Kashmiri voices that began gaining prominence in the post-abrogation period. Their works did not always take overt political positions, but subtly mapped the psychological, social, and cultural consequences of conflict.

Jamal, whose book Loal Kashmir: Love and Longing in a Torn Land became available to readers in January this year, tells ThePrint that there has been a slow clampdown on legacy media and other important voices in Kashmir over the past few years. “That this censorship is getting extended to books from/on the region is shocking but not surprising,” she says, adding that most of the works getting banned are non-fiction academic, historic, journalistic books on the political situation in Kashmir.

“When there is an erasure of such important documentation, it becomes even more imperative for more Kashmiris to tell their stories through various means of literature, media and other forms of storytelling—however small or big. This in itself becomes an exercise in not forgetting,” she says, adding that the decision has left her disheartened.

But at the same time, Jamal does not want to stop writing. “I wouldn’t shy away from writing another book when the time comes, or from telling our stories in any way I can. I will always want to speak truth to power.”

Kashmiri award-winning author Mirza Waheed says the authors on the list include some of the world’s finest historians and thinkers who have written on Kashmir. Bans on books are the worst kind of censorship as they “attack” knowledge and its transmission from one mind to another, he tells ThePrint.

“A political culture that permits such a thing cannot survive for long,” he says, “because books, thoughts and words are like spring water, they always find a way to flow on.”

This is an updated version of the report.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Restoring J&K’s statehood won’t be enough. Kashmiris need to be treated like other Indians

Zenaira Bakhsh please be assured that no matter how much you keep this fight continuing, we too are ready to not lose Kashmir at any damn cost and after the genocide of Kashmiri Pandits our motivations are on the up to never lose Kashmir from India. Banning or not banning the books will continue. Parties at the center like BJP or Congress will keep coming and going but one thing will forever be constant and that is Kashmir will remain in India and every Kashmiri will remain an Indian forever. If you want to live peacefully you are welcome but any attempt for secession will be met duly. That’s our commitment from the rest of India. We also never forget as Indians how many sacrifices we have made for Kashmir. Just remember this!

To say nothing of the hefty sums from anti-Bharat forces that these authors and the rest of their ilk will continue to write for, and hide behind the moral superiority of “writing for generation with no access to truth.”

No wonder Ms. Bakhsh feels so strongly about the ban on books. But one can safely bet that she did not feel just as strongly about Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses ban. Or even care about Rushdie getting stabbed, and almost dying, because of the fatwah on his book and him.

Ms. Zenaira Bakhsh has always championed the cause of the terrorists and Kashmiri secessionists. Her articles for The Print are watered down for quite obvious reasons. But even a cursory glance at her articles on other platforms (e.g. Coda, etc.) clearly shows where her loyalty lies. Add to it, her absolute disgust and contempt for Modi and BJP.