Bijapur: Mukesh Chandrakar had a dream: to have his own house.

The 34-year-old journalist from Bijapur in Chhattisgarh had even bought a plot of land from his YouTube earnings and was hoping to begin building his dream house soon.

“He had Rs 3 lakh saved in his bank account, untouched, to start building a house of his own, because he never had one,” Ranjan Das, a fellow journalist who knew Mukesh well, told ThePrint.

The plot now stands empty, marked by erect iron pillars, one of which bears a packet containing Mukesh’s ashes, tied there by his family.

Last week, the police found Mukesh’s body in a septic tank in Bijapur.

Police said the young journalist from Chhattisgarh was allegedly beaten to death by a contractor, Suresh Chandrakar, his brothers and an aide on 1 January. Mukesh’s body was recovered two days later on 3 January from the septic tank at one of Suresh’s properties.

Mukesh had recently exposed alleged corruption in a Rs 120-crore road construction project. The original tender for the project was Rs 50 crore, but the cost had escalated to Rs 120 crore without any changes to the scope of work. His investigation led the state government to initiate an inquiry into the matter.

Police have arrested Suresh along with his brothers, Ritesh and Dinesh, and his supervisor, Mahendra Ramteke, for allegedly killing Mukesh. They suspect Mukesh was killed for the story he did for NDTV’s Raipur bureau exposing the shoddy quality of roads built by Suresh’s company.

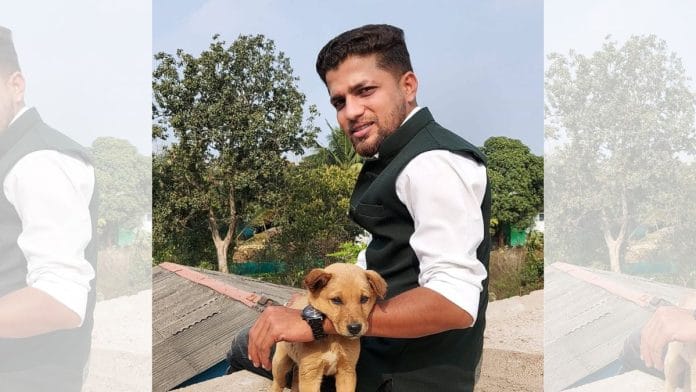

Mukesh Chandrakar was a household name in Bijapur, known for his fearless reporting on his YouTube channel, Bastar Junction.

Locals relied on him for coverage of major events, from operations against Maoists in nearby forests to everyday civic issues. Mukesh was known for his hard-hitting stories, which highlighted the struggles of people in Bastar’s remote villages, the plight of villagers caught in the crossfire between Maoist rebels and security forces, and the poor quality of infrastructure, including roads, in the region.

Sushma Haldar, a 26-year-old resident of Bijapur, remembered Mukesh for his YouTube reports, particularly his in-depth coverage of the Naxal issue from deep within the forests.

“I remember his face having watched his videos on YouTube. He was the most famous reporter who reported on all issues of Bijapur,” she said to ThePrint.

Also read: 8 DRG jawans, driver killed in Bastar as Maoists detonate 25 kg IED hidden beneath road

Passionate journalist with a big heart

Mukesh had a short but extraordinary journalistic journey.

Born in Basaguda, some 50 km from the Bijapur district headquarters, he was sent to a boarding school in neighbouring Dantewada. Mukesh and his older brother, Yukesh, were raised by their mother, an Anganwadi worker with a meagre salary.

His journalist friends recall he used to survive on corn and flour in his childhood.

Mukesh was inspired to enter journalism by his brother Yukesh, who had joined the media while Mukesh was completing his graduation.

Local colleagues remember Mukesh as a passionate journalist who never let anything get in the way of chasing a story.

They also remember him for his generosity and willingness to go out of his way to help people.

Ranjan Das had been closely acquainted with Mukesh since 2016 when he moved to Bijapur from neighbouring Dantewada to work as a correspondent for a local newspaper.

“I had got a decent job opportunity but had no accommodation or means to arrange for it and hence was unsure of coming here to Bijapur. However, when I approached Mukesh, he asked me to come and he will arrange,” Ranjan Das told ThePrint.

“I had nothing with me. Just Rs 4,000-5,000 in my pocket and I came on a bike to Bijapur. Mukesh offered me shared accommodation in the same hut he was staying in. I could not even pay rent for the first three months but Mukesh never complained,” he added.

A correspondent with a Raipur-based national daily said Mukesh was the go-to man for everything in Bijapur at any time.

“He was always ready to help people who knew him and never ran out of ideas to support others. His murder will have a chilling impact on other journalists in Bijapur and across the Bastar region, as it will be a constant reminder of the direct repercussions of their work,” the correspondent said.

The first story and rise to fame

Mukesh was part of a tightly-knit team of journalists who worked together closely in Bijapur because of the hostility they faced both from the administration and the Maoists. The team included Ganesh Mishra, Ranjan Das and Chetan.

Mukesh’s journalism began with the once-popular Sahara Samay channel in 2010, reporting from remote parts of Bastar rarely seen or explored by people outside of the region.

In his pursuit of what his journalist friends say he described as the “hidden” Bastar, Mukesh once stumbled upon a waterfall deep inside his home district of Bijapur. He reported on the waterfall and compared it with several other famous waterfalls popular with tourists.

“His reporting on the waterfall brought the Nambi waterfall on the tourism map of Chhattisgarh,” said his journalist friend Ganesh Mishra.

After Sahara Samay, Mukesh joined the ETV network later acquired by Network 18.

Mukesh gained recognition alongside his friends for his pivotal role in the negotiations that secured the release of CRPF commando Rakeshwar Singh Manhas, who had been abducted by Maoists during an exchange of fire in April 2021.

Recalling the incident, Mishra said that he received a call from a senior Maoist commander about a CRPF commando being in their custody and asking for his help in mediating negotiations with the government.

Mishra said the Maoist commander asked him to assemble a group of trusted men to facilitate the talks and it was Mukesh who became the architect of the negotiations that led to Manhas’s release.

In the pinned tweet on his X timeline, Mukesh can be seen riding a bike with CRPF commando Rakesh Manhas sitting pillion along with three other bikes ridden by his journalist friends.

ले आये @crpfindia के वीर जवान को।@AmitShah @HMOIndia @ipskabra @ipsvijrk @IpsDangi @IPS_Association @bhupeshbaghel @tamradhwajsahu0 pic.twitter.com/sxIljeUnAd

— Mukesh Chandrakar (@MukeshChandrak9) April 8, 2021

However, as he gained prominence and TV channels in Bijapur flocked to him and his friends for interviews, he apparently got delayed sending the feed to his own employer.

This led to a tiff with his bosses in Raipur. A journalist working with a national daily, who had spoken to Mukesh months before his murder, said that was the day when he hung up a call with his employers and decided to work on his own.

A man of dreams

Nearly a month after the CRPF commando incident and his clash with his former boss, Mukesh entered the world of YouTube journalism.

He started his own channel named Bastar Junction in May 2021 where he produced ground reports from the deep interiors of Bijapur district.

Ranjan Das recalled that he was never known for mincing his words as a journalist and was outspoken about issues concerning marginalised people like tribals and the poor in the region.

“He never toed anyone’s line. He spoke against both the establishment and the Maoists in cases where he found anything wrong,” Ranjan Das recalled.

For his bold stance on issues related to tribal people and the lack of government initiative to improve their lives, Mukesh was nicknamed “JNU” by his journalist friends.

“He used to be very vocal about these issues and leaned towards the ideology of the left,” Ranjan said.

In one of the hundreds of video reports on the channel, Mukesh is seen covering the death of a 10-year-child who was killed by the impact of an improvised explosive device (IED) planted by the Maoists.

He also reports the death of a 6-month-old infant caught in an exchange of fire between Maoists and security forces in Gangaloor village of Bijapur.

In many of these videos, Mukesh can be seen reporting on the ground from Naxal strongholds, offering insights into Maoist operations and the parallel government they ran, complete with courts, in areas under their control.

“He was never afraid of even calling out Maoists. Once during his reporting, he questioned their arson of public property. He asked if Maoists really cared about the resources and why would they be burning them. After that, Maoists had indirectly sent him a message showing their displeasure too,” Das said.

Das also drew attention to the plight of journalists in Bastar, and Bijapur in particular, where they face threats from both powerful civilians and Maoists for speaking the truth.

Mukesh’s journalist friends also recalled how he passionately followed the coverage of conflict zones by international news channels and wanted to model his YouTube channel on them.

They said Mukesh dreamt of making Bastar Junction as big as some top news channels in Raipur and New Delhi with a big office and several reporters who would report from the hinterlands.

With an impressive 1,77,000 subscribers, Bastar Junction had started providing a stable income to Mukesh, his journalist friends recall.

“On average, YouTube earned him Rs 20,000-22,000 per month, which was a dream income for people who had risen from extreme poverty,” Mishra explained.

Apart from a big office, Mukesh also hoped to use his YouTube earnings to help build his dream home.

Pramod Chauhan, a 40-year-old businessman who would have been Mukesh’s neighbour, recalls how he refused to ask him for help even though he was in the construction business.

“He always valued personal relationships. He didn’t ask me for help with construction despite my being in this field because he didn’t want to hamper our personal relationship,” Chauhan told ThePrint.

“It’s a huge setback for his family and overall society here. He wanted to get construction started on this plot,” he added. “He also wanted to visit Switzerland for holidays but could not do it because he could never manage the money.”

The last story

Barely a week before he died, Mukesh produced two hard-hitting stories from Bijapur’s Naxal-affected areas at the end of 2024.

One was on the state of teachers in government-run schools and the other on roads constructed by Suresh Chandrakar in the former Naxal strongholds of Bijapur.

The two stories published on 24 December highlighted the challenges faced by local Shiksha Doots (education ambassadors), who teach tribal students deep inside forests in makeshift schools, and the poor condition of roads between Nelasnar and Gangaloor villages in Bijapur.

The story on Shiksha Doots who hadn’t been paid for three months, prompted the Chhattisgarh government to step in and announce that 332 Shiksha Doots would finally receive their wages.

The impact of the story underscored the transformative role of Mukesh’s journalism in amplifying the voices of the unheard and in holding institutions accountable.

Mukesh’s death, which sparked outrage among journalists, highlighted the risks faced by journalists reporting from troubled areas like Chhattisgarh.

Mukesh’s brother, Purushottam, said the Chhattisgarh government should implement laws to protect journalists so that no other journalist suffered the same fate as his brother merely for doing his job—to bring the truth to the people.

NDTV’s regional resident editor, Anurag Dwary, said Mukesh paid a price for exposing the truth.

“As a journalist, my colleague paid the ultimate price for exposing the truth. It’s a stark reminder of the risks journalists take daily in pursuit of accountability,” Dwary said in a statement to ThePrint.

“We stand in solidarity with his family, and we demand a swift and impartial investigation to bring those responsible to justice. His sacrifice will not be in vain, and we will continue his fight for transparency and justice.”

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also read: SIT to probe murder of Chhattisgarh-based freelance journalist Mukesh Chandrakar