New Delhi: A high-paying data entry job in Thailand, with a salary in US dollars, and visa processed within three days of the offer. For an Indian aspiring to build a life abroad, it seemed like the perfect opportunity.

Lugging suitcases filled with dreams of working in an IT park overlooking Bangkok’s shimmering skyline, they eagerly boarded their flights. But the landing didn’t stick.

Immediately after their arrival in the Thai capital, they found themselves on an eight-hour journey, escorted by “armed men in military uniforms”. Shuttled between three vehicles before finally crossing a river on boat, they arrived at their new workplace—a ‘scam farm’ with towers named from K1 to K10, at Myawaddy, on the Myanmar side of the Thailand-Myanmar border.

ThePrint tracked down two men from Haryana who were lured to Thailand in the name of a data entry job at a company called ‘Taiwan 7 Star’ at different times in 2024.

Straight from the horse’s mouth, these accounts offer an in-depth understanding of how ‘scam farms’ operate, the cyber scams they pull off, and how they swindle targets out of millions of dollars by impersonating women and using the ‘dropshipping model’ as bait.

At the ‘scam farm’ in Myawaddy, for instance, which the two men described as a “massive call centre,” there were endless rows of computer terminals. Each was equipped with hundreds of SIM cards and multiple devices—a mix of iPhone and Android—besides an introduction to the ‘type of fraud’ to be perpetrated and a detailed script.

Some got the “US and Germany project,” but most Indians were assigned to the “India project”. The names indicate the country of the targets.

There was no time to waste. As soon as they completed their “induction and training sessions,” recruits were thrust into grueling 16-hour shifts to achieve what they described as “strict” deliverables.

“There was no way out. Deliver or get punished,” said the 25-year-old from Sirsa who worked at a ‘scam farm’ called KK Farms. On his first day, he saw people from Myanmar, the Philippines, Indonesia, Nepal, Cambodia and Pakistan—all typing away on their keyboards. “They were being overseen by people who were also translators. Higher-ups were mostly Chinese so translators helped us understand their commands.”

He also recalled seeing female models (Thai, Indian and Pakistani) on video calls against different backdrops.

More than 500 like him, employed at ‘scam farms’ in Southeast Asia, were repatriated to India on 10 and 11 March via an aircraft arranged by the Indian Air Force. This was one of the largest such operations to date. ThePrint reported earlier in a two-part series (read Part 1 and Part 2) that this multi-billion dollar cyber scam industry landed on the radar of Indian investigative agencies after the sudden boom in ‘digital arrest’ scams.

But the subsequent crackdown has little to show since the entire operation is based in a foreign country and arrests of a few agents, mule account holders or session initiation protocol (SIP) providers would hardly dent the fortunes of these hundreds of ‘scam farms’ operating on an industrial scale across Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia.

‘Developers, receptionists & killers’

For the 25-year-old graduate from Sirsa quoted earlier, the job was anything but routine data entry. He was asked to make a profile in the name of a woman and, for the next few days, that would be his identity. His task? To establish a rapport virtually with a man from a list of dating and matrimonial platforms handed out to him. These included Shaadi.com, Jeevansathi.com, Tinder, Boo, Tantan, and Truly Madly, among others.

He then had to cultivate the relationship to the extent that the target became comfortable enough to fall headlong into a trap.

“I took two identities, Ankita Mishra and Anika Mishra, and spoke to several people online. For a display photo, we used pictures of three models working with us. One was from Pakistan, one from Delhi and one from Thailand. If it was Shaadi.com, we used pictures of models from Delhi and Pakistan and for Tantan, the Thailand model,” he said.

The operation, he explained, was structured into three tiers.

The first tier comprised “developers” tasked with making contact with potential targets online, gathering basic information including name, age, occupation, and an indication of the target’s financial status.

Once these details were collected, they were passed on to the second tier, the “receptionists”. They engaged with targets, initiating conversations and gradually building a relationship over several days with the aim to con.

The third and final tier was the “killers”. They swiftly dispersed stolen funds across multiple accounts spanning different locations before converting them into cryptocurrency. This tier consisted of the most experienced lot, among them engineers and financial experts who laundered the proceeds of crime using mule accounts and other tricks of the trade.

Having worked as a ‘developer’ as well as a ‘receptionist’, the man from Sirsa recalled, “Sometimes, we found it hilarious, sometimes we actually felt very bad.”

His admission of empathy betrayed by a smirk, he added, “Even after being duped, the men would beg us to keep talking to them, convinced we were actually women, even after they had lost their money. They seemed too desperate for love”.

How exactly did they convince targets to part with their money? Read on to find out.

Love, and finally, a proposal

The second man, from Faridabad and in his 20s, and who worked at KK Farms for six months, told ThePrint male targets would usually respond after seeing the model’s photo as the display picture. “Some were interested in marriage, some wanted a date, some only needed a woman to talk to.”

Armed with information on the target gathered by ‘developers’, the ‘receptionists’ would strike a conversation about “love, life in general and how lonely it is to not have anyone faithful in life”.

The next step was exchanging contact numbers. “It surprised us as well to see how people believed everything we said and willingly shared personal details over chat, all in a virtual setting,” said the man in his 20s.

Once the target was hooked, the scammer would act as if they shared the same interests as the target. Then came the video call. This is where the female models would play a more direct role. They would appear on the video call, and pretend to be in love with the target.

This virtual fling would continue for a few weeks during which the scammer would tell the target that, for them to get married to each other, the woman’s family would expect the target to be financially stable, even wealthy. Posing as the woman, the scammer would tell the target that she earns Rs 5-6 lakh each month in commissions. This would pique the interest of the target and, according to the man from Faridabad, “that used to be our cue.”

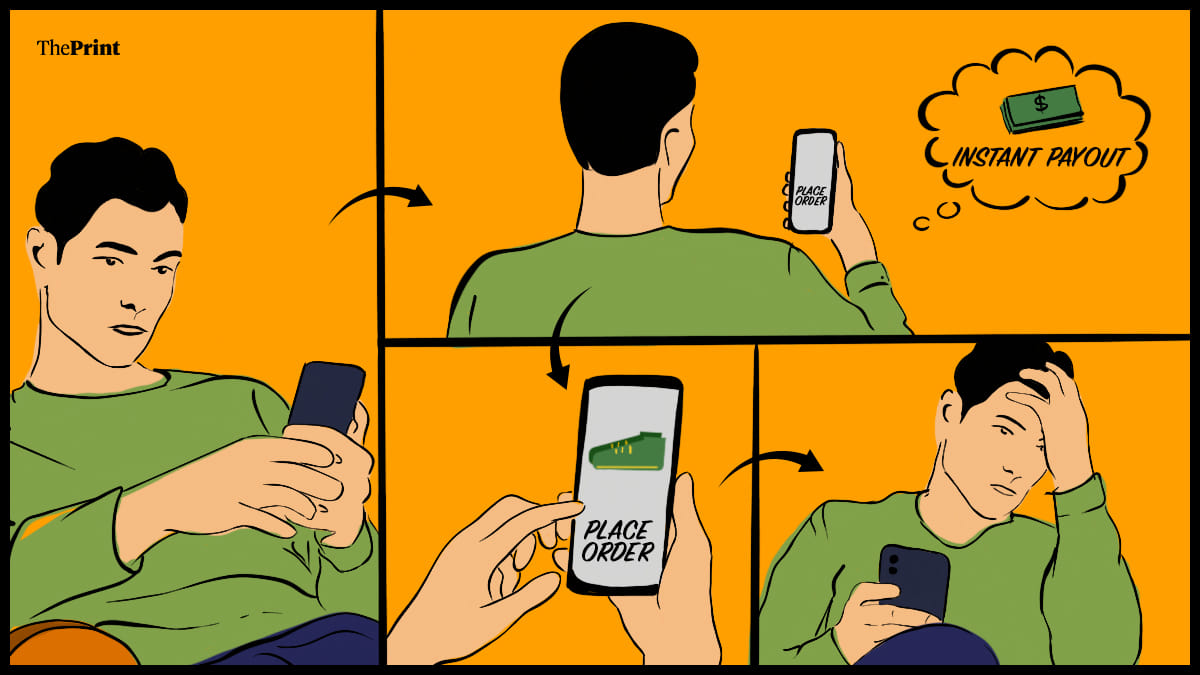

The script was simple: “We also told them, let’s tell our parents we work in dropshipping, as my parents would not approve of us meeting on a dating app. We suggested it would be better if we worked on the same project, so we could later say that we met at work.”

Dropshipping is a model where one promotes products and operates an online storefront, similar to Amazon.

“We told them after a customer places an order with a wholesale dealer for a certain amount, the order is forwarded to the dropshipper, and the customer is notified. On each order, we told them we earn a 10 percent commission plus the money they originally spent,” explained the man from Faridabad in his 20s.

Having convinced the target that commissions earned through dropshipping would pave the way for a happily married life, the scammer would then send a link asking the target to download an app. Acting on the scammer’s instructions, the target then placed an initial order of around 100 dollars, and the scammer would ensure the target received an instant payout of 100 dollars along with a 10-percent commission. This was done to gain trust.

By this point, the scammer already had the target’s bank account details.

“This would encourage them to invest more, and we would gradually push them to raise the stakes,” said the 25-year-old quoted earlier. “To maximise their earnings, many would increase their investments to 1,000 to 15,000 dollars in the second order itself, depending on their financial status.”

The scammer would then advise the target to place multiple orders of higher value, claiming payouts for larger transactions required 7-8 business days. The target would believe the scammer and continue investing. And then the ‘killers’ entered the picture.

Recalling one particularly distrurbing exchange with a target, the 25-year-old from Sirsa said, “There was a client from Mumbai who put Rs 2.5 crore in this after taking a personal loan and lost all this money.” The client, however, still wanted to continue talking to the woman (a Pakistani model) on chat and video calls.

“Sometimes It was unbelievable that even after losing so much money, they stuck to us, believing they would get the return and also get to marry or at least meet their love interest,” said the 25-year-old.

Adding, “Once a client realised he was being conned, he would stop putting in money and delete the app. And then we would move to the next target.”

He also revealed that each scammer was at any given time conning “more than five to six clients”.

No deliverables, ‘no food’

Asked if he was ever tortured for non-performance, the man from Faridabad in his 20s said, “Not me or friends I made there…But they were definitely strict about deliverables, else we were not given any money or food.”

The 25-year-old from Sirsa recounted an incident involving a couple from Rohtak. The wife was pregnant, and when her husband refused to work, he was subjected to electric shocks.

“That served as a warning for everyone…After that, no one dared to refuse work.”

Many from the ‘scam farm’ secretly wrote emails to the Indian embassy in Thailand asking for help, which ultimately led to the crackdown. Upon their return, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) recorded detailed statements of those repatriated.

A source in the security establishment said these individuals come from different states and had been working in Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia for a long time. “While many were deceived into going, others were fully aware of what they were getting into. Many even accepted the work after being deceived, since they were paid well and started sending remittances back home.”

The source added that all of them, upon their return, were questioned by police from different states and the CBI and then let off, but “this is just the tip of the iceberg”.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Make women pregnant, get rich—Bihar’s cyber scam goes to a whole new level