Kashmir: Aged 55, Ali Mohammad appears weary doing contractual labour work close to his house in Astanmarg on the outskirts of Srinagar. Out of social stigma, he always wears a mask when outside—behind it is a face that has no resemblance to the one he lost around 37 years ago.

“I should have at least been given proper surgery to reconstruct my face,” says Ali. His niece, sitting by his side in the courtyard of his modest house, recounts the events of 37 years ago. “It was a normal day, and as he was ascending the very same slope that you came from, the bear just appeared out of nowhere and latched onto him.”

“His best efforts at fighting it off failed and it took multiple surgeries over six months for him to return home. His marriage was called off,” she adds.

A small straw inserted into the nose cavity is Ali’s breathing aid. He wheezes while he talks, and is only able to take small sips of tea with a spoon.

“Unfortunately, the government is such that they would rather let people die to save the bears,” he laments, weighing in on the lesser-known threat in Kashmir, of the Asiatic Black Bear, locally known as the reechh or more vernacularly, bhalu.

The human-bear conflict, a result of both climate change and human action, is proving to be as damaging as any other in the politically volatile Kashmir valley.

The Asiatic Black Bear is native to the cold temperate forests that dominate the Kashmir valley and its surrounding mountains. Its conflict with humans is also posing a significant challenge to its conservation, especially in Kashmir where human activities often overlap wildlife habitats, and the tussle is increasingly becoming visible.

“The conflict was always there. I think the reporting has increased because everyone today has a phone camera”, Bilal Bhat, senior assistant professor at the Department of Zoology, University of Kashmir, tells ThePrint over phone, acknowledging that the conflict was bound to occur more frequently as the boundary between humans and nature blurs.

The Jammu & Kashmir department of wildlife protection recorded 2,357 Asiatic Black Bear attacks on humans in the Kashmir Valley between 2000 and 2020, of which around 95 percent resulted in injury, including grievous ones as in Ali’s case; the rest were fatal.

“The bear attacks usually in self-defence, unlike attacks by a leopard that are mainly predatory in nature,” Mehreen Khaleel, who runs Wildlife Research and Conservation Foundation, an NGO in Srinagar that works on researching conflict and mitigation strategies across Kashmir, tells ThePrint. “Therefore, the bear, even after inflicting life-long deformities, is often forgiven. But leopards, which often lift children to consume them, are often pursued and killed by the locals.”

A study enlists the reasons for the human-bear conflict in Kashmir: large-scale conversion of natural habitat to orchards and agricultural fields, continued human encroachment into wild, and finally what is unique to the high-security region, military installations and international border-fencing that block wildlife movement, disturb or fragment habitat, and subsequently divert bears towards human habitations.

A deeper analysis in another study shows that land-use under agriculture experienced the steepest decline (−5 percent) from 1990 to 2017 whereas horticulture gained the most (+4.29 percent) in the period. Since fruits are highly sought-after by black bears, wildlife researchers have linked the change from agriculture to horticulture as the leading driver of increased and adverse human-bear interactions.

Residents and stakeholders in the Valley also allege lack of initiatives from the government and forest department to address the human-bear conflict and the absence of scientific research and studies to address the issue.

However, former Regional Wildlife Warden of Kashmir, Rashid Naqash (now at the office of the Chief Wildlife Warden), begged to differ, saying a lot of work was being done in this regard.

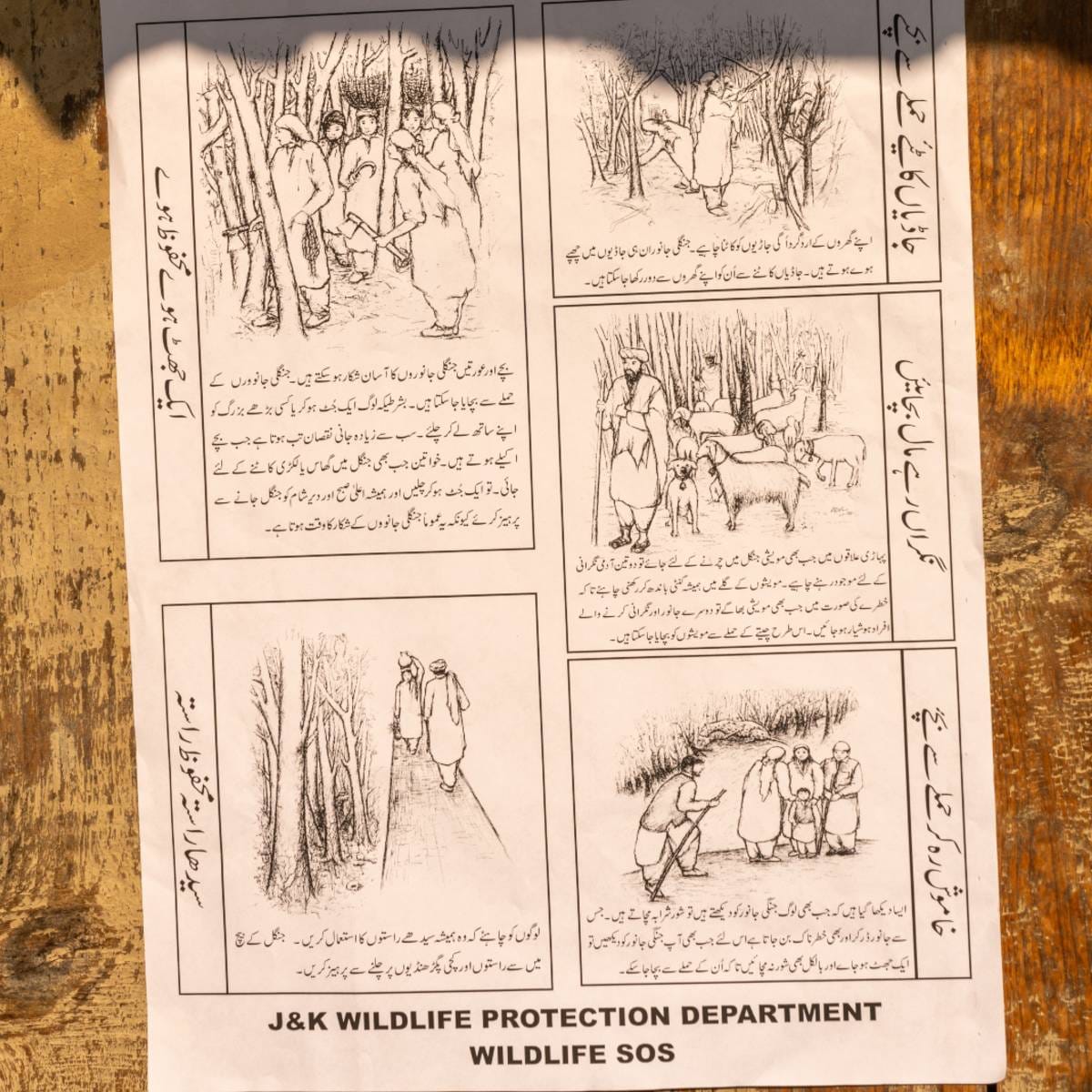

He believes the solution to the problem doesn’t lie in installing cages or relocating the bears, but in creating awareness among those who live in close proximity to forests and are vulnerable to the animals. “The forest department is doing a lot of work in this regard. We have made videos, and we conduct regular school programmes,” he tells ThePrint.

Also Read: Who has the right to be ‘angry’ in Kashmir? Certainly not its power elite

Apples, maize & bear raids

The reechh or bhalu has a particular fondness for apples, a fruit being cultivated in large numbers in Kashmir.

“Moving to apples is a natural choice for farmers in Kashmir since fruits usually fetch more income,” says Shakeel Shah, who owns apple orchards across 1.2 acres in Gotli Bagh (Ganderbal), 30 km north of Srinagar. “But it comes with a cost: a lot of upkeep and maintenance. And of course, there are the bears who come during this time (end of August) when the apples haven’t ripened and the trees are laden with fruit.”

Shakeel, however, points out that even though fruit orchards have proliferated across the valley, fruit is the bear’s secondary choice. “Given a choice between maize and fruit, the bear will always go for the maize,” he tells ThePrint.

According to a study specific to Kupwara in North Kashmir, local communities attributed 95 percent of crop losses to black bears even though other wildlife such as monkeys and porcupines also caused damage. Bhat, who co-authored the study, observes that since Kupwara is heavily forested, the local communities are more vulnerable.

“Incursions are much more common in areas that are close to forests, where it is easier for the bears to come down and raid the fields,” he says. “If you were to take Sopore’s example, which is also very famous for producing apples, you will not find so many black bear-related incidents, simply because the orchards are often surrounded by populated areas. So, proximity to the forests plays a big part as is the case with Kupwara.”

Speaking about food preference, he explained that besides being preferred by bears over all other food, maize is also grown in hilly areas that are close to, or adjoin forests, thus giving the bears easier access to the crop. In the study conducted at Kupwara, even though the average economic loss per farmer was estimated at around Rs 5,000 for maize and Rs 32,000 for apples, the quantity of maize lost to bears was far greater than of apples.

“By rural standards, these are huge losses,” says Bhat. Such is the case with Anderwan, a remote village with 100 percent agrarian economy. High up in the Kangan tehsil of Ganderbal district, it is the last village on that section of road. And as is the case with such villages, an Army camp lies in its way, where all outsiders are required to register their names and vehicle numbers.

Every year, for at least two months before maize is harvested in August-September, the villagers barely get any sleep at night.

“You have to see it to believe it! Sometimes a hundred bears come down from the jungle to raid the fields and all we can do is have the dogs chase them, light torches and beat the dhol (locally-made drums). We don’t have any firearms to protects ourselves against such attacks,” says Haji Barkat Ali, who is the sarpanch of Anderwan that is inhabited by the Gujjars, a largely pastoral community.

“They simply run from one field to the other. If we aren’t this vigilant, the bears will eat off our crop completely. As it is, because of them, we are left with only around 30 percent of our total yields.”

Haji Barkat Ali laments about lack of initiatives by the forest department whose officials, according to him, make false promises whenever they visit the village.

“No wiring is done around the fields on the lines of Nishat and Brein (both suburbs of Srinagar). Perhaps if they plant some edible trees for the bears on the forest fringes uphill, they will stay there and not come down at all,” he told ThePrint.

Science, or the lack of it

According to experts, the greatest challenge in mitigating the human-bear conflict in Kashmir is the lack of scientific research and studies to address the central and ancillary issues around it.

Official data from J&K department of wildlife protection from 2020 till 2023 shows that 1,862 bears were rescued or relocated from the valley, and around 539 cages were installed for capturing them. Both these figures were the highest among all other wild animals and far greater than for the other big predator, the leopard.

“The people simply want the animal relocated since there is a lot of anxiety around economic losses,” says Bhat. “And it isn’t just maize and apples, it is also livestock that comes under attack–sheep are particularly vulnerable since they have no natural instinct or defences.”

According to Aaliya Mir, who heads the NGO Wildlife SOS in Srinagar, since locals are desperate to get rid of the bears, wildlife officials have to install cages and capture them in order to pacify the people. But she questions the effectiveness of such measures.

“You see we haven’t had any sustained, long-term studies on black bear behaviour and its use of the landscape in the valley, like we did for the brown bear in Sonmarg region,” she tells ThePrint. “We haven’t even conducted a census in recent years. The last time we radio-collared black bears in Kashmir was 2006-07, but since then, there have been drastic changes to the landscape.”

“I had suggested that we insert a microchip, the size of a rice grain, subcutaneously in the bear’s body. This way, the next time we trap it, we’ll know all details of its morphology and its capture date through the unique number. Most importantly, it will tell us whether we are capturing the same bear again and again, since even after translocation, bears have a strong homing tendency and tend to return to the areas they have been captured from.”

“Only when we know the number of bears and their range, can we devise mitigation strategies,” she says, elaborating on the need for science in dealing with the human-wildlife conflict.

Asked about whether there is a proposal for getting a headcount on bears, Bhat says the best researchers and scientists can do is to mention it in recommendations at the end of their research papers.

He also attributes climate change in addition to easy access to human-generated food for the changes in black bear behaviour. “Earlier, when I went to Dachigam (National Park near Srinagar) between 2005-06, between November and March, I never saw bears as they were all in hibernation. But now my students are seeing them in February as well, during the peak of winter,” he says.

“Since we have some observation of active black bears in the winter, the rising temperatures have possibly led to shorter hibernation/denning periods. Due to the scarcity of natural food in winter, the black bear is likely to come out of its natural habitat, facing more encounters with humans,” he explains.

Also Read: Read the Kashmir verdict. It’s time to stop treating it like a national security crisis

An indigenous technique

Back in Gotli Bagh village in Ganderbal, Mehreen and her co-researcher Tahir examine an assortment of nylon ropes that are suspended from tree to tree, and eventually connect to a machan (a wooden tower) around 15 feet above the ground.

“The technique is fairly simple,” explains Mehreen, demonstrating its use.

At the slightest hint of disturbance to the apple orchards by a wandering bear, a person who spends the night in the machan, pulls at the nylon rope that is connected to an empty tin can with a bell-like suspension in the middle.

“When tugged on with force, it creates a considerable amount of noise which will alarm the bear and set it off,” she says.

“It is an effective technique, since we trick the bear into thinking there are lots of people around,” adds Shakeel Shah whose very orchard Mehreen is working in.

“But it also means that we need to have one person stay up all night and keep vigil. And the bears return after a few days. Also, the slightest carelessness on our part would mean a huge loss of apples,” he rues.

Security tussles & conservation

With forest cover among the highest in India and huge biodiversity, Kashmir is also unique with regards to unprecedented military mobilisations and substantial security presence owing to a particularly hostile international border.

“We (Kashmiris) deal with the constant anxiety of sudden lockdowns and embargos on our life,” remarks Mehreen. “It is therefore difficult to convince people here to care about wildlife.”

When asked whether there was any scientific proof to show the impact of military conflict on wildlife, Aaliya Mir referred to her ongoing study on brown bears in Sonmarg and what happened during this year’s conflict at the border between India and Pakistan.

“We noticed that some brown bears we had collared were in the same range where the conflict was unfolding, and the upper ranges are all connected. I can’t give all details since the paper we will be publishing these details in is currently under review. But on the 9th of May, using radio telemetry, we observed such rapidity in the movement of bears that we had never seen before. This was indicative that they were running in distress due to the shelling and firing ongoing in the region,” she tells ThePrint.

Yet, researchers’ encounters with the security personnel are not always adverse, as Bhat points out. “During our study of Markhor and Goral (both goat species native to the Himalayas) in Kazinag (National Park) between 2019 and 2022, they (military personnel) used to call over phone and, in fact, send one person to accompany us during our research trips,” he says. “The problem is when the situation is tense, then priorities shift rapidly.”

The way forward

The Kupwara study co-authored by Bhat found that the combined losses due to bear raids for farmers cultivating both maize and apples was 26 percent of annual earnings, which was unsustainable for subsistence-based economies.

In terms of mitigation, the study’s results revealed that while traditional deterrents such as shouting, drum-beating and night-guarding remained the main defence strategies in the face of bear raids, the animals were also prone to habituation–a phenomenon wherein animals learn to ignore non-lethal deterrents.

Then there is the very real risk that these methods pose to the participants, since they exposed them to direct confrontation with the bears. This is compounded by the fact that in Kashmir, compensation is offered only for human injuries and fatalities resulting from wildlife attacks. There are few provisions for livestock losses and none for crop damage caused by wildlife.

“Conservation of wildlife should also include people,” says Bhat, while commenting on designing area-specific strategies to deal with human-wildlife conflict. “Experiences with crop damage and livestock depredations make people’s attitudes towards conservation very negative.”

According to him, “if we think of landscape level approaches, to connect sections of forest, then conflicts will surely lessen. But they won’t completely stop”. Others believe that locals and black bears in Kashmir are currently in an evolutionary phase. “The bears and humans will both coevolve and eventually learn to live with one another,” says Mehreen.

Shaz Syed is a TPSJ alum currently interning with ThePrint

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Medieval Kashmir was confidently multicultural. And dazzled the world with art and ideas