New Delhi: Onions are onions, right? Wrong. India is in the middle of an onion crisis with retail prices soaring above Rs 100 per kg in some parts of the country, and stocks are being imported from Egypt and Turkey to tide over the crisis and keep citizens happy.

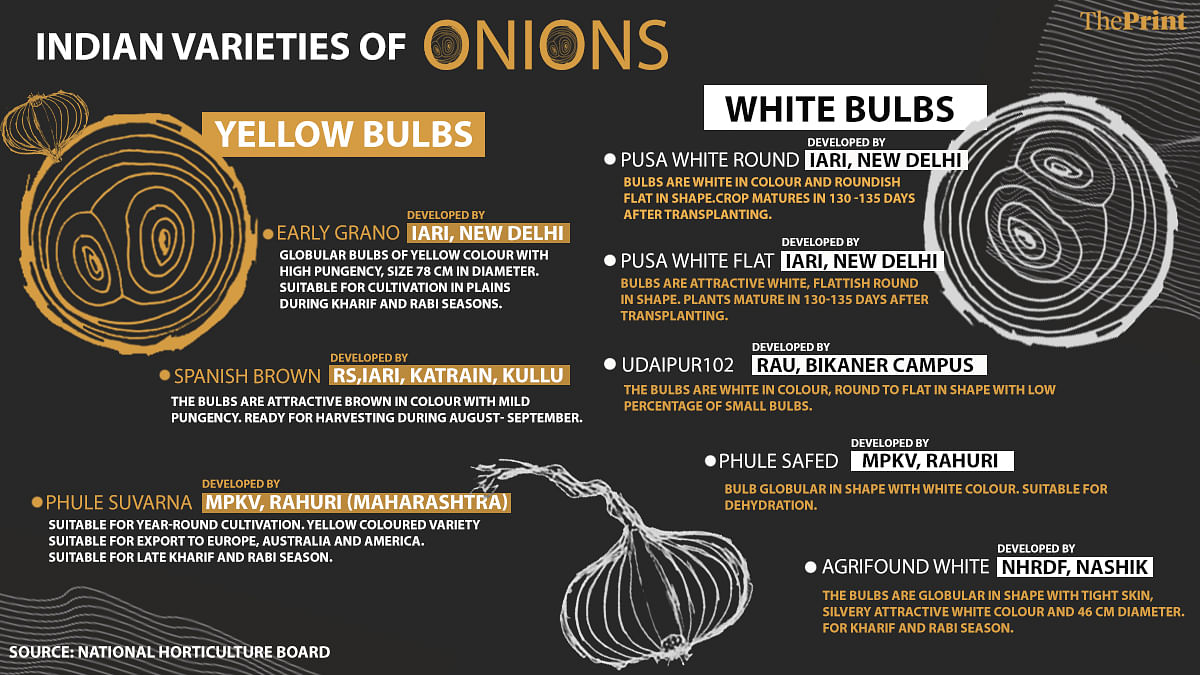

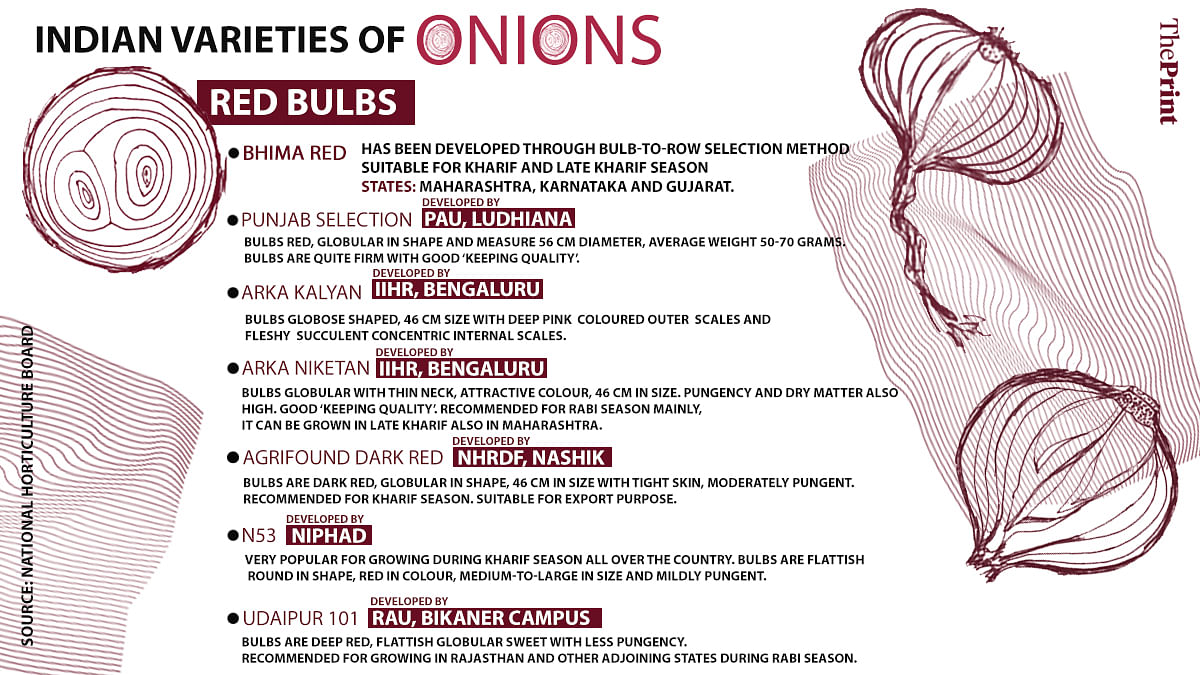

Surely, all the onions can’t taste the same, look the same or add the same pungent touch to your korma, sambhar, or even chowmein. And they don’t — India itself produces at least 30 types of onions, ranging from shades of deep purple to yellow-white, each with its own distinct flavour.

Food historian Pritha Sen points out that “knowing one’s onions” means to be properly informed about something. ThePrint tries to help.

A brief history

Over centuries, the onion has risen to become the bedrock and backbone of Indian food, forcing government after government to take sharp measures like banning its export and increasing imports to keep its supply in abundance and its price low.

In truth, however, the onion didn’t always hold this hallowed position in Indian society. Thousands of years ago, no one was bothered about the supply of onions, because there was no simply demand for them.

The onion, in fact, was looked upon with some disdain for a very long time.

“Before the Mughals arrived, India relied on a more ginger-based diet. Onions and garlic were virtually unused,” food historian Sen told ThePrint.

Over 2,000 years ago, the father of Ayurveda, Charaka, in his treatise Charaka Samhita, glorified the onion as a vegetable capable of healing joints and aiding digestion.

However, four centuries later, other Ayurvedic texts banished onions, terming them ‘tamasic’ food that inspired lethargy and lust.

The Chinese traveller Xuanzang (also spelt as Hiuen Tsang or Hsuan Tsang), who came to India in the seventh century AD, observed that few people ate onions, and those who were found out were “expelled beyond the walls of the town”.

It was only after the Mughals arrived, between 1526 and 1556, that onions won over the mainstream. Certain sects still avoid garlic and onions — religious Brahmins and Jains, for example, but even then there are exceptions.

“I have a Tamil Brahmin friend who doesn’t touch red onions because they’re considered tamasic. But, on occasion, she will use small white onions, available in Madras stores, which aren’t as pungent and aren’t considered to be as tamasic,” said Marryam Reshii, food critic and writer.

Also read: If 10 years from now you see 30 types of onions in Indian markets, this is how it happened

Season, size and pungency

The taste of an onion depends on some overlapping factors: The type (red or white), the season it is sown in, what point it is collected at, and the climatic conditions in which it is grown.

Onions are grown all year round in India, and collected at the end of three harvest seasons — kharif (between October and December), late kharif (January to March), and rabi (March to the end of May).

A senior official at the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) added: “Kharif onions have higher moisture content and are more perishable, while the ones sown in the rabi season have less moisture and can be stored for longer periods of time. The moisture content affects the pungency, but most people wouldn’t be able to tell.”

As onion prices soar and their sizes appear to get smaller and smaller, exporter Deepak Roy explains that all this has to do with the climate.

“These onions are dark and small because they’ve been picked up prematurely. The rains that ravaged Maharashtra, where a bulk of onions are grown, has forced farmers to collect the onions faster, before they are fully matured,” he said.

Onions with higher moisture content also tend to be lighter, ranging from pinkish to white, and are less “spicy”. Those with less moisture are darker, and more pungent and bitter.

“The thing about Indian onions is that they’re ideal for cooking sabzi, daal, and other staple foods in our diet. We’re importing Turkish onions for the first time, and we’re yet to see if they’re equally suited to our cuisine,” the NAFED official said.

According to the official, the Turkish onion is too high in moisture content, and not pungent enough, while the Egyptian onion is bitterer than what the Indian palate is used to. The most comparable onions come from Bangladesh and Pakistan, he added.

Reshii added that there are quick-fixes to help the onion suit the Indian palate.

“You can add it to water to remove its pungency, or add it to vinegar to enhance sourness. Onions have been the subject of controversy in the past, but they’re so commonplace now that we forget to examine them closely,” said Reshii.

Also read: NAFED wasted over 30,000 MT onions, more than half of its buffer stock, amid soaring prices

Different locations, different styles

Certain states use particular kinds of onions — in Tamil Nadu, the pinkish Bellary onion dominates, while in Karnataka, it’s the more spherical rose onion (which earned a GI tag in 2015).

“I’m particularly drawn to an onion found in the Northeast, which is tear-drop shaped and quite garlicky — except it isn’t garlic,” said Vanshika Bhatia, chef at Together at 12th in Gurugram.

With local produce comes local practice, too. “If you lay an onion on a flat surface and smash it with your fist, it isn’t pungent at all. Farmers in Maharashtra discovered this technique and eat it raw with their rotis,” Reshii said.

In West Bengal, ‘onion payesh’, a kind of kheer made from onion, is a popular dish, historian Sen recalled.

Also read: Modi govt ignores Turkey’s Kashmir criticism — because India needs its onions

Nonsense news