WhatsApp groups, Insta Stories, Twitter trends — when India wants to raise its voice in protest or amplify the voices of those who need help, social media is their best friend. And this is also why governments resort to internet restrictions. But India has a long history of protests, long before the age of retweets and shares, before cheap data plans and influencers.

ThePrint speaks to freedom fighters and Emergency-era activists to find out how.

From horses to bathroom stickers

Dr. G.G. Parikh, a 96-year-old freedom fighter from Mumbai, tells ThePrint that he had heard many stories of how activists mounted horses, going door to door to spread awareness of the revolution and try to get young men and women to join in the revolt of 1857. “There was absolutely no other way of spreading information but verbally, yet Indians came out in huge numbers, all across the country to join the first struggle for independence,” he says.

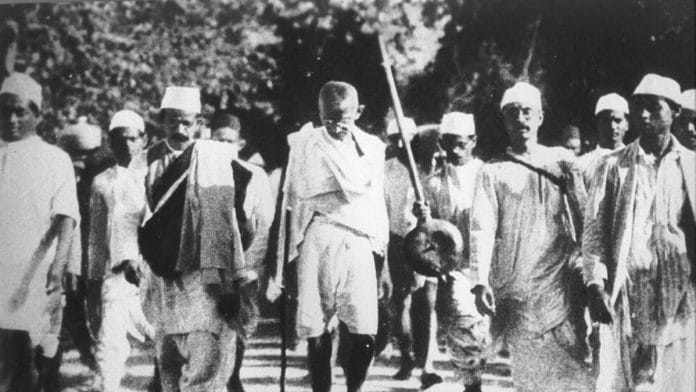

When Parikh participated in the freedom struggle, he recalls, it was the charisma of the leaders that drew crowds to different agitations. “Everyone just wanted to hear Gandhi and others speak.”

Abhay Mokashi, a professor at Mumbai’s Xavier Institute of Communications, was an active underground worker during the Emergency in 1975. He recalls, “Communication channels were shut, yet within a day, gossip of Sanjay Gandhi slapping Indira Gandhi spread throughout the country, in every house.” Mokashi calls it “the whisper campaign that effectively took down Mrs. Gandhi’s government”. Those who were at the top of this chain of information knew just how to use the power of words to spread information, and spread it like wildfire, the former journalist further notes.

But it wasn’t just about getting word out, but also how to do it within a budget. Today, cheap data plans mean that anyone can amplify anything from the comfort of their bed, be it which artistes are performing at Shaheen Bagh or the need for lawyers to help detained protesters.

Before all of this, people had to rely on their own creativity. One popular method of creating awareness was through litho-printed posters.

Mokashi would frequent Mumbai’s Nagpada neighbourhood, which was known for litho printing. “We’d just take a sheet of paper and put some pressure on a litho (stone) and the negative would get printed on paper; that was the cheapest way of printing posters. It was just like creating a rubber stamp,” he says.

To not reveal the posters that he was printing, former SFI member Prasad Manjrekar would write backwards on a paper with a stencil. “It was tough work, but my handwriting was good so I was always roped in for this work,” he chuckles. “I had to write so many leaflets for protests that cadres would actually stand guard while I wrote, fearing that I’d run away!”

Mokashi eschewed a stencil for a cyclostyle. The machine had a thin sheet of paper that would perforate its contents onto a thicker sheet to make a stencil, to be further put into an inked roller, used for photocopying. “We’d take that thin sheet of paper and put it in the typewriter, making transparent impressions on it.”

They would later just trace the impressions with a pen onto a thicker sheet with the help of a carbon paper — a cleaner and cheaper way of printing posters.

Also read: How kind strangers helped me file story after CAA protests led UP to shut internet down

Putting hand-drawn stickers in public bathrooms was another much-used method, Mokashi recalls. “One had no choice but to read while they were doing their business,” he adds.

To avoid raising suspicion, protesters would print posters separately. “Printing 400 posters together would have ensured our arrest, so 10-12 of us would print 10-20 posters in different batches from different stationery shops, so nobody would find out what we were up to.”

During the many agitations in Assam, an English lecturer recalls how an organisation called Assam Gana-Sangram Parishad provided a common platform for different social unions to guide the movement and to disseminate information. Public meetings and newspaper ads were used to inform people about next steps, says the lecturer not wishing to be named.

“We’d distribute pamphlets and hold community gatherings in college canteens to convince kids to join the cause,” notes Manjrekar, recounting how SFI members would approach colleges all over Mumbai.

Surendra Manan, a filmmaker from Delhi who organised and participated in worker unions, reiterates that mobilisation for a specific protest comes second, first is educating people about the issue, which is what worker unions did during company lunch breaks in canteens.

“We would go out in groups in the dead of the night to put up posters near the company, to tell the employees what we were planning, and the bosses would never find out what we were up to until the day of the protest,” he says. “One person would paste gum on the wall, another would come and quickly stick the paper.”

“Once at night, a cop caught us, but before doing anything he looked at the poster, read it intently for a while, turned around and asked us to leave,” says Manan. The cop actually joined the protest.

Facing police violence and detentions

Today, if a protest is thwarted by the police, if Section 144 is imposed or metro stations are shut down, people find out within minutes and shift their agitation elsewhere, as was seen in Delhi on 19 December. And if a protester is detained or injured by the authorities, mobilising efforts to reach them is a lot easier than it was back in the day, without internet or even telephones. Often, one’s family didn’t even know if they were dead or alive.

The English lecturer from Assam was part of the 1979 protests demanding the detention of illegal immigrants in the state that ended with the signing of Assam Accord in 1985. He recalls there was police firing in a godown that killed two or three protesters, causing utter panic. Several protesters from his village went underground, and their families had no idea of their whereabouts or condition.

The lecturer and some of his friends headed for the suburbs nearby after dark. “We went to the houses of the missing people’s relatives to see if they had taken refuge at some aunt or uncle’s house. Once we located a few, they’d give us information about the others and their location. We went to house after house like this the entire night and then returned to inform the parents about their kids,” he tells ThePrint.

Also read: Modi said CAA protests anti-national, just like Indira Gandhi did before declaring Emergency