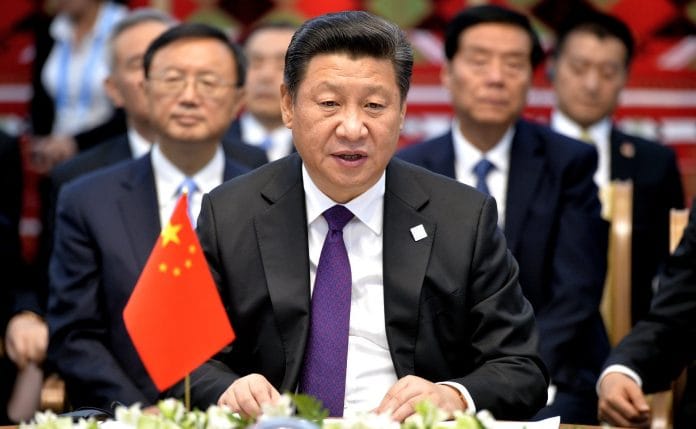

Insights of two professors at Harvard University offer a granular look at the recent rise of Xi and his methodical pursuit and consolidation of power.

Some essentials of the current Chinese strongman Xi Jinping’s leadership clearly reveal that his pursuit of power does not have any firm ideological moorings. Neither a classical Marxist/Leninist or Maoist; nor a reformist like Deng and Jiang Zemin; or a technocrat like his predecessor Hu Jintao, Xi has attempted to create his own brand of Chinese nationalism moored in both Maoist and classical Chinese thought.

Two professors at Harvard University have been spearheading the analysis of Chinese leadership from the days of Mao to Xi: Ezra Vogel, Professor Emeritus of Social Sciences and Roderick MacFarquhar, the Leroy B Williams Research Professor of History and Political Science.

Their insights offer a granular look at the recent rise of Xi and his methodical pursuit and consolidation of power.

Capitalising cleverly on a large segment of population that has very little connect with the trials and tribulations of modern China’s founding fathers, Xi has very deftly steered the political discourse towards a brand of aggressive Han nationalism that looks more at reclaiming China’s lost pride and strength and setting right the wrongs of colonial exploitation during what he often repeats as the ‘Century of Humiliation.’

Though not endowed with an intellect as sharp as Deng or Jiang Zemin, his protégé, Xi is said to keenly study the successes and failures of all great leaders of the 20th century and contextualise them in the contemporary Chinese milieu.

His aversion to any form of liberalism is heavily influenced by Mikhail Gorbachev’s spectacular failures and contribution to the break-up of the Soviet Union. This is reflected in his emphasis on strengthening state enterprises and reigning-in private enterprise, especially if he sees the threat of that enterprise emerging as alternative power centres like the Russian oligarchs who clamour for political power.

Consequently, Xi’s style can said to be completely autocratic wherein he demands complete written loyalty from his team, including the entire PLA leadership. Not since Mao has any Chinese leader assumed complete leadership of the PLA as Xi has as Chairman of the CMC and commander-in-chief. His appearance in military uniform at a recent military parade is testimony to his attempt to take complete control of the PLA and for good reason.

If Xi has an Achilles’ heel it is either the economy, or control over the PLA, which has been known to flex its muscles at times when some strongmen within its ranks have not got their due within the CPC or the CMC. One of the ways in which Xi has limited the power of the PLA is to reduce the number of military regions and ensuring that rival power centres are limited.

For decades, the PLA was the dominant force in the CMC leadership, but over the last decade, the induction of the other chiefs (PLAN, PLAAF and PLARF) has somewhat reigned in the PLA’s dominance. The appointment of another ex-PLAAF chief, Ma Quiliang as a vice-chairman of the CMC is one way in which Xi is distributing power. He will ensure that there will be no challenger to his power from within PLA ranks unlike in the past when strongmen like Lin Bao and Chu had the muscle to challenge Mao, albeit without success.

While Xi has been adept at consolidating power with speed, his tenure, so far, has been marked by tepid economic performance. China could face severe headwinds if it does not maintain the economic momentum of at least 7-8 per cent growth that is essential for adequate wealth creation and keeping a restive urban population politically dormant.

A look at the ‘big seven’ of the CCP-CC Politburo Standing Committee reveals that five of them are newly appointed and considered to be Xi’s men with the lone representative of the old guard being Prime Minister Li Keqiang, who is a considered a reformist and protégé of the former president, Hu Jintao. MacFarquhar calls the once vibrant economist ‘a sad figure in Chinese politics’ as he seems to have been completely marginalised by Xi Jinping. The task of China’s recovery has been assigned to the two ‘Shanghai’ strongmen in the politburo, Wang Huning and Han Sheng.

An excellent depiction of the complex web of the apex Chinese leadership has been put together by the Fairbank Center for Chinese studies at Harvard and a comparison of the composition before and after the 19th CPC Congress is available here.

Xi will complete his term second term as President, General Secretary of the CCP and Chairman CMC in 2022 and with no successor named as has been the trend earlier. There is speculation that the rules of the game may change to give Xi a ‘Mao-like tenure’ as China’s supreme leader in the 21st century and allow him to steer the ‘Chinese dream’ to its logical conclusion.