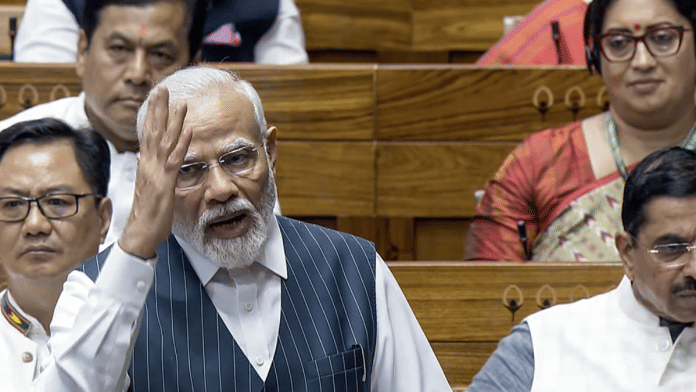

New Delhi: The Narendra Modi government introduced the women’s reservation bill — renamed ‘Nari Shakti Vandan’ — in the ongoing special session that met for the first time in the new Parliament Tuesday.

The Constitution (One Hundred and Twenty-Eighth Amendment) Bill, 2023, introduced in the Lok Sabha by Union law minister Arjun Ram Meghwal, proposes reserving one-third of the total number of seats for women in the Lok Sabha, state legislative assemblies and the legislative assembly of the National Capital Territory of Delhi.

Within the proposed 33 percent reservation, one-third of the seats will be reserved for women belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. However, there is no sub-quota for Other Backward Class (OBC) women — a demand of political parties such as the Samajwadi Party (SP) and Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD).

According to the bill, the reservation will be for a period of 15 years from the commencement of the act. The seats reserved for women will be rotated after each delimitation exercise. There will be no reservation in the Rajya Sabha or the state legislative councils.

There is little clarity as of now as to when the proposed law would come into force. Significantly, even if the bill is passed, it’s unlikely to be implemented before next year’s general election.

Currently, 14.36 percent of the total MPs in Lok Sabha are women while in legislative assemblies, it varies from state to state.

The bill inserts Article 334A, a new provision that says the reservation will come into effect only after a delimitation exercise is undertaken for this purpose, which in turn can take place only after the census.

This means that till the time the redrawing of constituencies happens, the new law won’t be implemented. And although the census was supposed to be conducted in 2021, it was put off because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s currently unclear when the census exercise will begin.

The women’s reservation bill has been one of the most contentious pieces of legislation because of significant differences of opinion among different political parties. It was first brought in the Lok Sabha by the H.D. Deve Gowda-led United Front government in 1996 but lapsed after the House was dissolved.

It was introduced again in 1998 and 1999 but stalled both times. In 2010, the then United Progressive Alliance government got the bill passed in the Rajya Sabha again amidst huge backlash from across the political spectrum, but it lapsed before being tabled in the Lok Sabha.

Also Read: ‘It will be short but of historic developments,’ says Modi about Parliament’s special session

What the bill says & how it’s different from the 2010 version

Section 334 A (1) of the Constitution (One Hundred and Twenty-Eighth Amendment) Bill, 2023, says that once it becomes law, it will cease to have effect after 15 years.

The bill also says that one-third of the seats will be reserved through rotation and it will come into force after each subsequent exercise of delimitation “as the Parliament may by law determine”.

However, the proposed law will not affect any representation in the Lok Sabha, the legislative assembly of states or the Legislative Assembly of the National Capital Territory of Delhi until their dissolution. This means that at the time of enactment of the new law, if a legislative assembly of the state is already in place, the law will come into force only after its term ends.

The provisions of both the UPA-era bill and this one are more or less the same. Both bills propose a quota within the quota for women belonging to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, but no sub-quotas for OBCs.

Significantly, the OBC sub-quota is one of the major reasons for the bill being stalled for so many years.

The only difference is that while the 2010 bill included reservation for the Anglo Indian community, the 2023 bill does not.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: ‘We are Vishwamitra, world’s friend & Global South voice,’ Modi in last speech in old Parliament