None of the laws enacted so far seems to have done its job as manual scavengers continue to die in pits and sewers.

New Delhi: Over the last 25 years, India has passed many laws to end the practice of manual scavenging.

And yet, people continue to die on the job — according to official data from the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis (NCSK), 123 manual scavengers have died on the job since 2017.

The latest incident was of Anil, a sewage worker from Dabri, Delhi, who died of asphyxiation on 17 September, while working in a 20-foot-deep sewer. Anil was privately hired by a local resident, who did not provide him with any protection gear.

ThePrint analyses the policies in place and how effective, or ineffective rather, they’ve really been.

Succession of policies

The first law against the age-old practice was the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993. It banned the employment of any person for manually carrying human excreta, as well as constructing or maintaining dry latrines.

Then, in 2007, the Self Employment Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers (SRMS) was introduced, which made this a national priority. But that didn’t solve the problem either.

These acts defined manual scavengers as those employed to physically clean dry latrines, not other unsanitary latrines, ditches and pits.

Then, on 6 December 2013, the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, also known as the MS Act, was passed.

This widened the definition of manual scavengers to include those employed to clean other unsanitary latrines as well. It banned the manual cleaning of sewers and septic tanks. It also asked all states to conduct a survey of manual scavengers and initiate the process of their rehabilitation.

Offences under this act are cognisable and non-bailable and attract stringent penalties.

Then, in 2014, the Supreme Court directed the states to conduct a survey of manual scavengers and initiate the process of their rehabilitation, and submit it to the NCSK, a statutory body set up by the government in 1994 under the ministry of social justice and empowerment.

However, there have been many hurdles in the implementation of these steps to abolish manual scavenging.

Also read: These technologies can end manual scavenging and save lives of sewage workers

Problem of identification

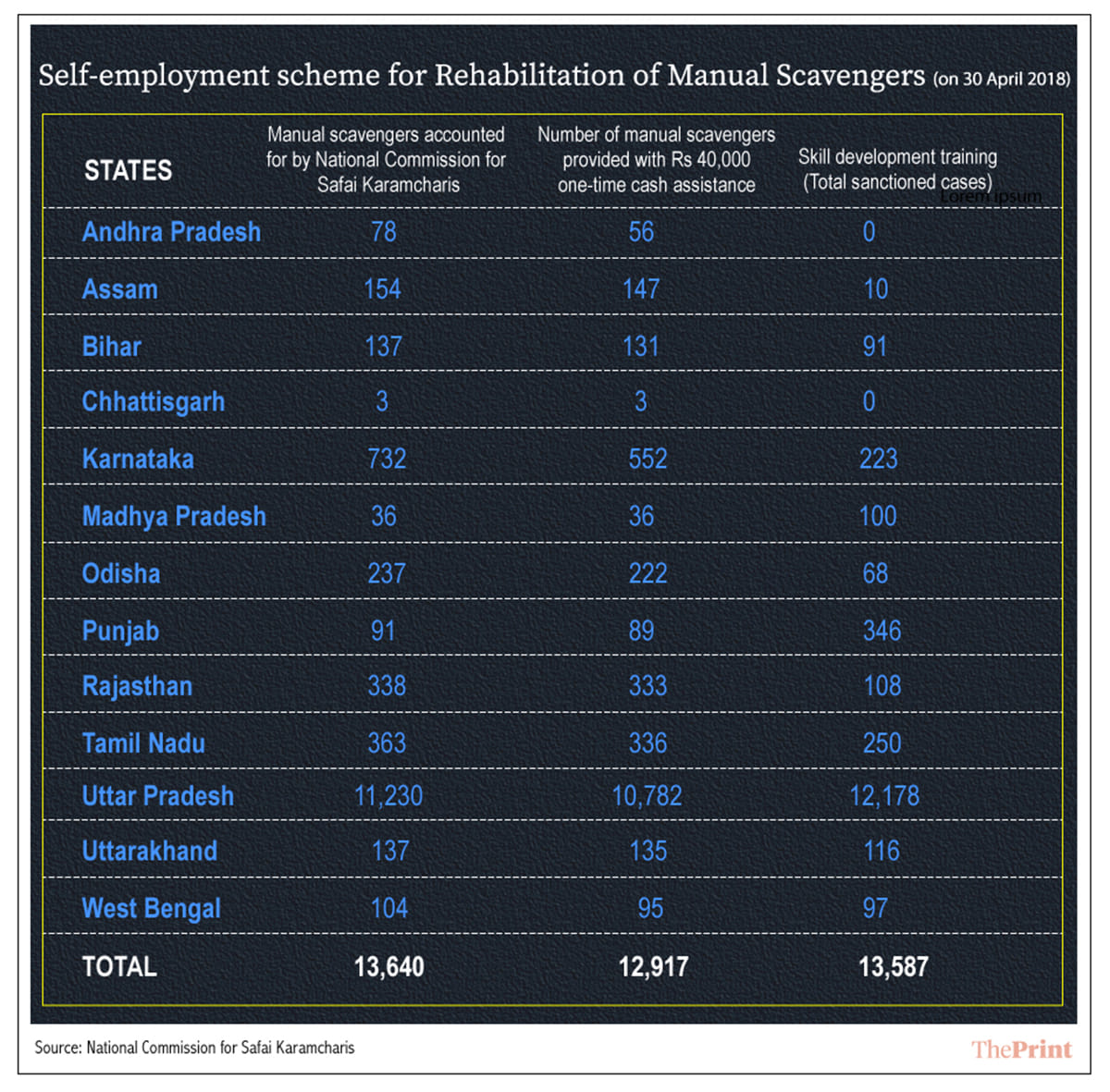

As of 30 April, 2018, only 13 states have identified the number of manual scavengers who live and work within their jurisdiction — 13,640.

“From 2013, when this act was brought into implementation, the identification by states was only 13,600 because the state governments were afraid that the moment they say that there are manual scavengers, they will have to admit that manual scavenging was happening,” said Narain Dass, secretary of the NCSK.

Now, the NCSK is conducting a new survey in 18 states — 16 that had not reported at all and two of the original 13 whose data was found to be inaccurate.

The NCSK has set up camps within states for the identification of manual scavengers, and is being assisted by other organisations such as the government’s think tank NITI Aayog, and NGOs such as the Safai Karmachari Andolan and Rashtriya Garima Abhiyan.

“We are helping the government in collecting the data. We help them identify places where manual scavenging is happening,” said Bezwada Wilson, founder of the Safai Karmachari Andolan.

What happens after identification

Of the original list of 13,640 manual scavengers, 12,917 have been given Rs 40,000 each as one-time cash assistance by the National Safai Karamcharis Finance and Development Corporation (NSKFDC), under the SRMS.

A total of 13,587 manual scavengers have been given skill development training, so that they can be rehabilitated. This training is given in fields such as driving e-rickshaws, opening kiraana shops and working as beauticians.

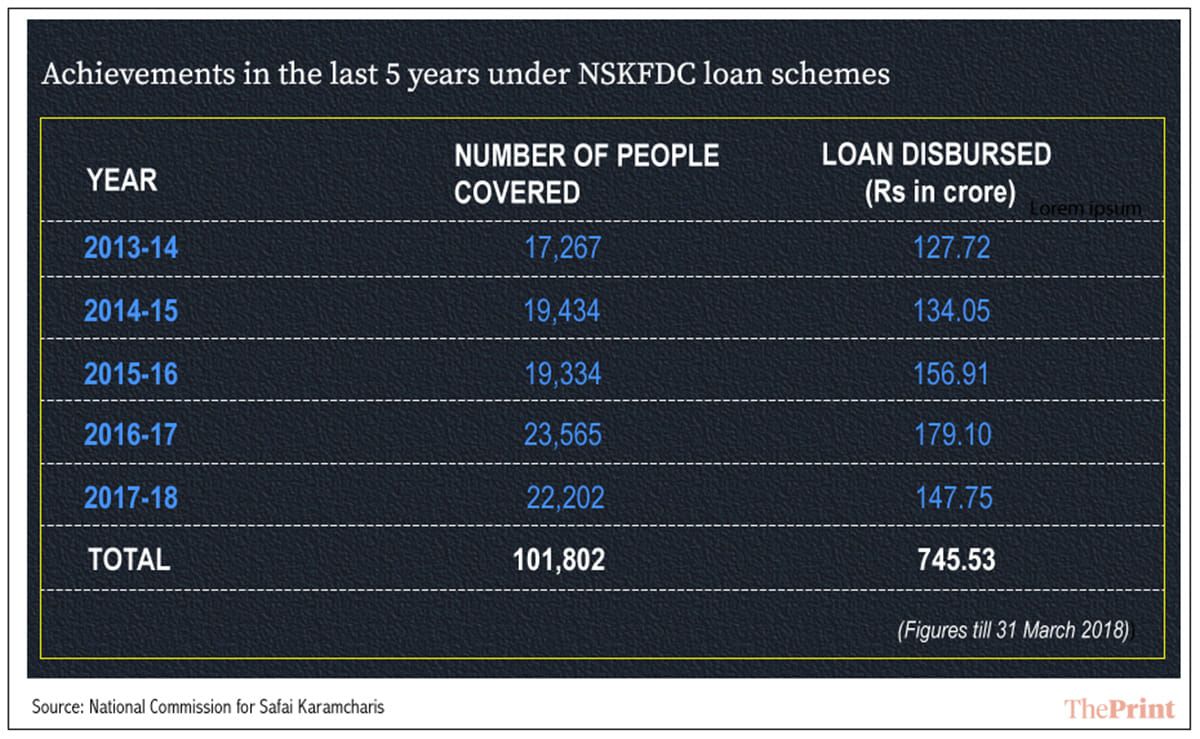

According to NSKFDC data, it has spent a total of Rs 745.53 crore in providing loans to these people over the last five years.

However, NCSK’s Dass admitted there had been problems in transferring compensation to workers, because their bank account details were erroneously recorded and the states had to be approached again for the data.

Dass said around 20,000 more manual scavengers had been identified under the new survey, and 7,000 of them had already been provided the one-time cash assistance.

“With the new national survey, we have made sure that the bank account details are recorded meticulously and are digitised,” he said.

The Central government had earlier released Rs 80 crore for compensating the original list of manual scavengers from 13 states, it has “now given us Rs 20 crores, which were are in the process of transferring to the new workers identified”, said Dass.

The money is transferred directly from the government to the NCSK, which is then distributed as direct benefit transfers to the notified manual scavengers.

“Everyone thinks this is an overnight process, but it’s not. There are complexities involved in the process,” said Dass.

Also read: Sewage worker deaths wouldn’t happen if India worked as hard on it as it did for polio

‘Failure’ of urban affairs ministry

Soon after the Narendra Modi-led BJP came to power, it launched the Swachh Bharat Mission, which is basically split into different schemes for rural and urban areas. The rural or gramin scheme falls under the ministry of drinking water and sanitation, while the urban scheme is handled by the ministry of housing and urban affairs.

In addition, the urban affairs ministry also runs the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation & Urban Transformation (AMRUT), under which the elimination of open defecation and scientific disposal has been made a priority. The main components of AMRUT, which was launched in 2014, included mechanisation of septage and rehabilitation of old sewerage systems.

Answering a question about sewage worker deaths, housing and urban affairs minister Hardeep Singh Puri told Parliament in February that “such cases are immediately taken up with the concerned state government to ensure payment of compensation”.

He also said the ministry has approved “836 projects with an estimated cost of Rs 32,456 crore in sewerage and septage management, as proposed by states/Union Territories in the entire country”.

However, the ministry has not done its job in terms of mechanisation or rehabilitation, said experts.

“The service providers in the sanitation sector are completely ignored by the state, which is resulting in this kind of distress,” Wilson told ThePrint.

“The government has to understand the communities involved, and understand the mechanisms required for the karmacharis to come out of this system. The government has become completely numb to safai karamcharis. The prime minister and the chief minister (of Delhi) are the ones solely responsible for this mess. It is a matter of lives, not just sanitation.”

NCSK’s Dass also put the onus on the ministry.

“The mechanisation of cleaning is to ensure that there is no hazardous cleaning. The precautions for the same are to be taken. This is something that the ministry of housing affairs has to handle,” he said.

“We have come up with a workshop module of two hours for the top management of municipalities, as well as for the ground-level stakeholders like sanitary inspectors, supervisors, contractors, etc,” said Dass. “We hope to sensitise them about the conditions of the act, so that modern methods can be adopted and sewage deaths can be avoided.”

According to Dass, the workshop will start this month, with support from municipalities and training partners from other organisations.

ThePrint reached the ministry of housing and urban affairs for comment but there was no response until the time of publishing this report.