On the journey, ThePrint meets an expat nurse-turned-relief worker, NDRF personnel, as well as some who have lost everything but want to get on with life.

Ernakulam: Usually, the busy rail route between Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram and Ernakulam offers spectacular views of mother nature. With the lush greenery of coconut trees and paddy fields and the wind blowing from the Arabian Sea in the west, it is a traveller’s paradise.

But there’s nothing ‘usually’ about August 2018.

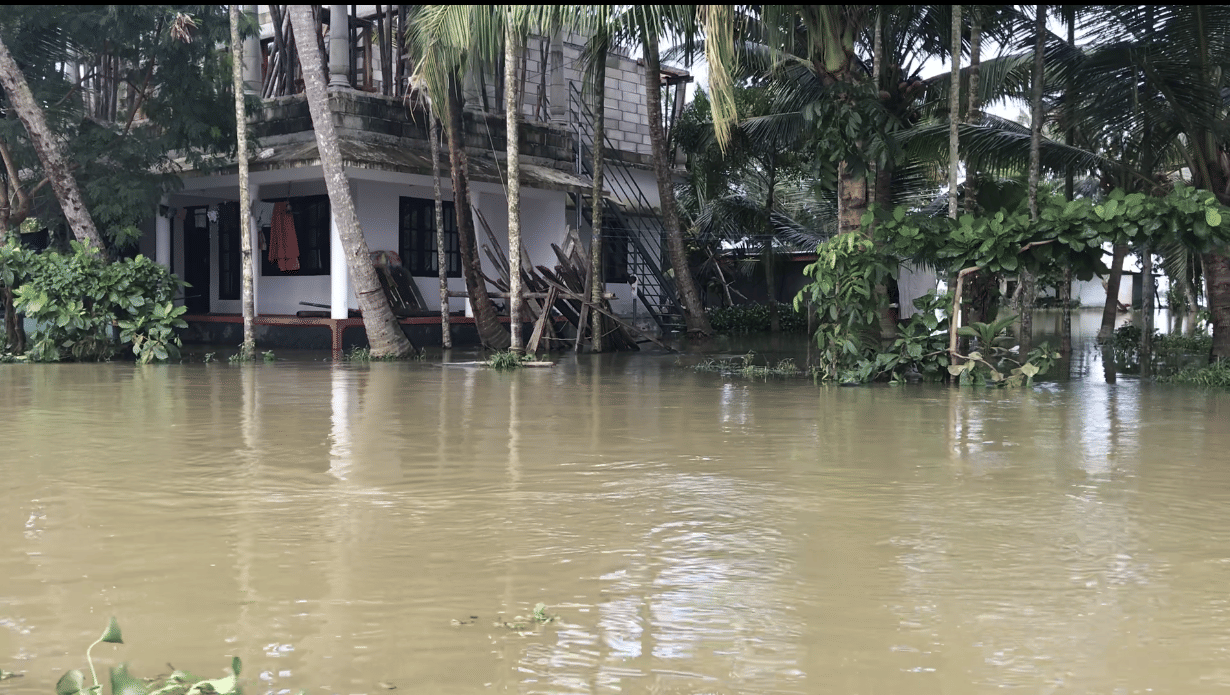

There are no more paddy fields with quaint little houses dotting the landscape. There’s just water, water everywhere, and the odd derelict house whose roof has either blown off or collapsed. Where the water has mercifully receded, there are people moving out vessels, chairs, clothes filled with slush and dirt, trying to dry out whatever is left of their material possessions.

Between 15 and 17 August, almost all trains stood cancelled, except those that were stranded in the middle of the floodwaters between Kozhikode and Ernakulam. Only now has some semblance of normalcy returned to this lifeline of the people, who are travelling back to their homes in the hope there is a home left to return to; a home that won’t collapse on them due to foundations weakened by the once-in-94-years floods.

Also read: Kerala’s Kainakary village, from a postcard of beauty to seven feet under

Tales of despair

Sarojiniamma is travelling with her 12-year-old granddaughter Devi. The old woman’s house in Pathanamthitta was severely damaged and water had risen to about waist-level before they were rescued and sent to a relief camp.

“After spending 10 days in the camp, I am now going to Kochi to meet my elder son; then we’ll go back home. But starting our lives all over again fills me with fear — there is absolutely nothing left,” she tells ThePrint.

“We are agriculturists; we have sent our son to college in Kochi. Now how will we pay his fees?”

Devi looks on shyly; she lives with her parents in a different home, but she shares her grandmother’s pain. “My books and clothes, everything is wet. I will have to go back and dry them,” is all she can say.

Shyamala is travelling with her extended family. A trained nurse, she had come down from UAE, where she works, to celebrate Onam with her loved ones. But then, calamity struck, and she has been helping out at a relief camp near Aluva. Even on the train ride, she is carrying a box full of emergency medication.

“What people need now are medicines to curb fever, cold and skin diseases. I have also asked my friends to come with mosquito repellents. I don’t think I can go back to my job soon, but this is also service, isn’t it?” she says.

Passing through the town of Thiruvalla in Pathanamthitta district, where the rains abated a couple of days ago, it is clear that the water level is still around two feet above the ground. It will still take some time to drain into the sea — and that’s even before diseases kick in, and long before people can get on with anything resembling ‘normal’ life.

There is also self-doubt, especially for someone like S. Unnikrishnan, a musician. Onam is that time of the year where he earns a few extra rupees, which help him out over the rest of the year. This time, though, every programme stands cancelled.

“How are we to survive? My wife asked me today, ‘couldn’t you have learnt any other skill?’ What am I to do?” he wondered.

Also read: Kerala’s snake-boat rowers were set for IPL-style race. Now, they don’t know what to do

Rescue personnel also have stories to tell

Every train zig-zagging through the state has large contingents of the National Disaster Response Force on board. Kerala has seen the deployment of the biggest contingent ever for rescue operations in the country, say officials. But they too have had their share of problems.

Several personnel have not slept for days. One would expect the country’s premier rescue force to hit the ground running once it arrives in a state, but they’ve faced issues too — primarily due to the language barrier, since Kerala does not have its own NDRF battalion.

“We don’t know the place and the local language. But on the ground, especially in remote areas, if we had to act immediately, we had to convince people that relief camps have been set up, and they needed to come with us. But we had to struggle. There are a few NDRF personnel from Kerala, but they can’t be everywhere,” said inspector Sachin Nalawade of the NDRF, Pune, on board the train.

For Nalawade and his team, who worked in the worst-hit regions of Pathanamthitta, Chengannur and Kottayam, another huge problem was the refusal of some people to leave their homes.

“In Champakulam, it took us close to two hours to convince them to leave their homes and move to a safer location. We had a diabetic patient, a lady who was paralysed, several elderly men and women, and infants. Handling all of them and moving them to safer zones, especially when the water levels were so high, was very challenging,” he said.

A new hope

As the train nears Ernakulam, the sun shines bright in the sky. The passengers around this reporter, despite the doom and gloom of the last few weeks, agree that it’s an apt metaphor.

They’ve faced the worst floods to hit their home state since 1924. But there’s still hope.