New Delhi: Dressed in a shiny red hoodie with flip-flops to match, the 20-something man emerges from a decaying brick hut. He primps his straightened hair, a small act of vanity, before covering his face with a gamchha (cotton scarf). He can’t risk being recognised by his “enemies”.

The man, Mohit (name changed), has been “lying low” for the last couple of years, he says. There are gunfights to be dodged and the special cell of the Delhi Police has been watching him like a hawk.

The former state-level wrestler-turned-outlaw is meeting ThePrint near Bakhtawarpur village in outer Delhi, but it looks like the middle of nowhere, with fields of barley and mustard as far as the eye can see.

He’s picked the spot because it’s seen as a relatively “safe zone” between the villages of Alipur and Tajpur, which over the last decade have become hotbeds for Delhi’s gang wars.

A few metres from the meeting spot is an earthen wrestling ring that has stood testimony to friendships that have turned bitter and bloody. Many of the boys who’d come here to wrestle eventually drifted into thuggery, which isn’t an unheard of phenomenon in village akhadas.

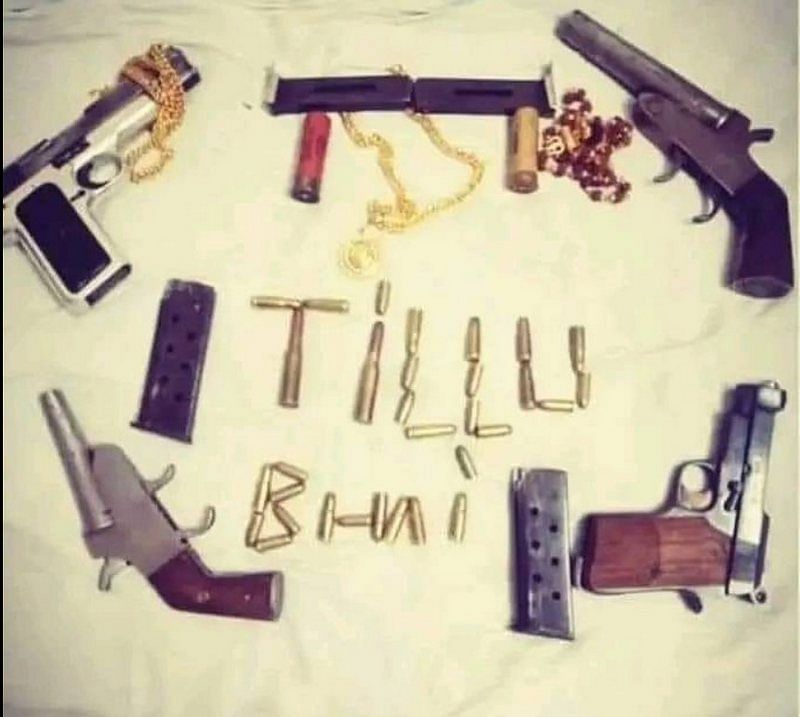

The blood feud between the rival gangs of Alipur and Tajpur even spilled over into Delhi’s Rohini court in September 2021. That Friday afternoon, two men dressed like lawyers opened fatal fire at ‘most-wanted’ gangster Jitender Maan alias Gogi. Another notorious criminal, Sunil Tajpuria aka Tillu, was arrested for allegedly masterminding the attack.

Gogi was from Alipur and Tillu is from Tajpur. The two were friends until they weren’t. For Tajpur’s Mohit, the hero of this story is Tillu — who he describes as “god-like” and a dispenser of justice — and the villain is the late Gogi, “the devil himself”.

The Gogi and Tillu gangs are just two among several organised crime groups in Delhi.

According to police sources, the city’s underworld is part of a larger network of criminal enterprises that operate across northern India. Many forge alliances and partnerships with each other, but also foment vicious rivalries and deadly grudges.

Yet, to many young men and boys, these gangs represent glamour, a chance to make quick money, and even get social media creds. Reels featuring flash cars, big guns, and occasionally death threats have their own kind of currency.

The problem is that getting into the ‘club’ is easy enough, but making a clean exit is harder.

As Zahid (name changed), a semi-retired member of the Hashim Baba gang put it: “Once you enter the underworld, there is no way out.”

Also read: ‘Pro-Khalistan terrorist’, India’s most wanted gangster: Who was Rinda?

‘You can never leave’

Mohit wears his paranoia on his sleeve, but Zahid, who is in his 40s, seems more confident, at least at first.

He welcomes ThePrint to his large well-decorated home, but once inside, the bravado slips a little. Perched on his draped sofa, he monitors all the entrances to his house through eight CCTV feeds.

He says he was serving a stint in Tihar Jail when he came in contact with gangster Hashim Baba, known for his penchant for murder, extortion, and gold chains. He says he’s been trying to leave, but it’s not easy.

“If I turn my phone off, a person will just drop by telling me ‘Baba wants to talk’,” he says.

“The options of survival are — you do their chores, pay them protection money, and sit with multiple CCTV cameras.”

But while both Mohit and Zahid claim that they are no longer active in their gangs, both seem to idolise their respective kingpins and keep close track of the latest news in the circuit.

“Baba is a pious soul. I will show you his latest photo,” Zahid says. With pride he fishes out a photo of Hashim Baba drinking a Red Bull and looking quite dapper in an Armani T-shirt.

However, Zahid admits that the “pious” Hashim Baba and other gangsters have no compunctions about luring underage boys into criminal activities. And of late it’s become even easier with the outlaw lifestyle being glorified in songs, films, and social media.

Catching them young

For the police and the general public, gangsters are dangerous criminals. But for a section of youth, the local mafiosi are Robin Hood-like figures — romantic anti-heroes who are rebelling against an unjust system and uplifting the oppressed.

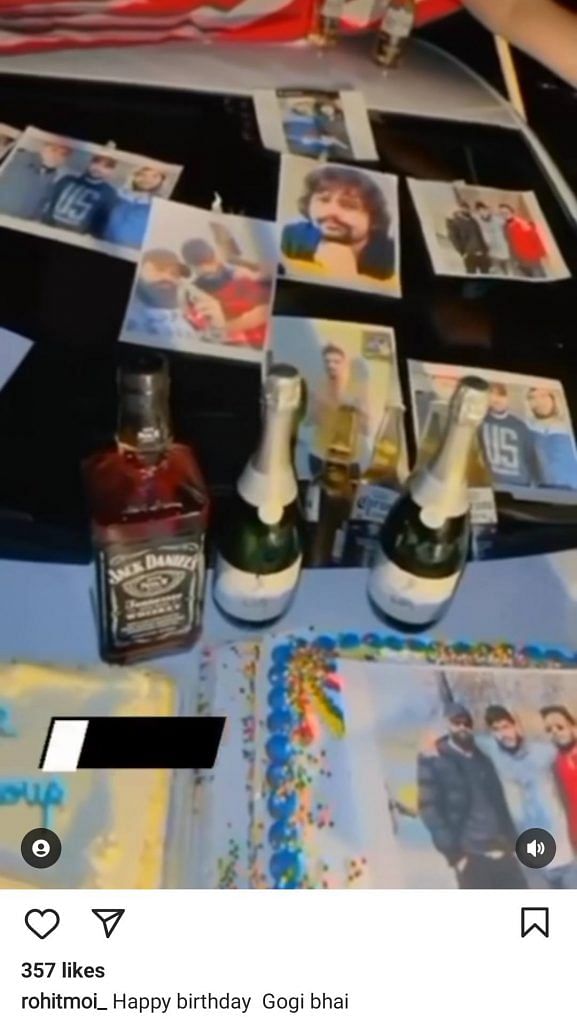

What helps this impression along is that many gangsters cultivate a larger-than-life image even as they live in the shadows. Some have a massive following on social media, and a celebrity-like status.

Trending hashtags of gangsters’ names, reels depicting their activities, and Facebook fan groups abound. When combined with catchy songs that blur the lines between violence, love, and money, this culture is irresistible to many.

When ThePrint scanned Facebook and Instagram, it found multiple videos and reels of boys trying to put on a macho show with such music playing in the background. Tracks by Punjabi singer Sidhu Moosewala, who was slain in gun violence last May, are popular but so are songs like ‘Gun Label’ and ‘Pistol’ by lesser-known artists.

Not only are the youth primed, gangs also actively try to recruit minors.

According to both the men, boys between the ages of 12 and 16 are seen as especially suitable for carrying out petty tasks. The main reason is to exploit the legal system: boys only get sent to juvenile homes for a few months (with rare exceptions), even for heinous crimes.

“It all starts with gang members giving the children a bit of money, taking a selfie with them, and, sometimes, driving them around in their cars,” Zahid says.

Once drawn in, the kids are then used to transport, sell, and store drugs, money, and even weapons. “In return, they will be given Rs 5,000 to 10,000 depending on the task. The boys are also happy to be able to afford a set of flashy branded clothes,” Mohit says.

Some of these boys eventually make it to the big league.

“At first, they are asked to do menial tasks —like a drop-off here or a pickup there. Gradually, the scale and frequency of these tasks increase. Eventually, these boys start to control and operate small parts of the business. Basically, in a timeline of six months, they become essential parts of the operations,” Zahid says.

This could extend to working as contract killers, but ultimately these kids are just pawns in the gang wars. Over the last few years, there have been several cases of teenagers doing the dirty work for gangs.

For instance, in May 2018, a 17-year-old boy shot murder-accused undertrial Dinesh Karalia at Delhi’s Tis Hazari court. The boy was a member of the Tillu gang and Karalia is a known associate of the rival Gogi gang.

In Sidhu Moosewala’s killing, 19-year-old Ankit Sersa was one of the alleged shooters. Sersa was a daily wage worker before he fell in with Punjab’s Lawrence Bishnoi-Goldy Brar gang. He was caught by the special cell of the Delhi Police in July 2022 and is currently in jail.

Sources in the police say that social media has greatly enhanced the appeal of crime for young boys. Rampant joblessness doesn’t help either.

“This tendency of using juveniles is a relatively new phenomenon. We can say that it has been on the rise over the last 10 years,” a police source says. He also corroborates what Mohit and Zahid say: gangs turn to juveniles because of the low conviction rates and leniency in court sentences.

Also read:‘Radicalised in Tihar’ — story of murder convict Naushad, accused in Delhi beheading

The politics of the underworld

Gogi and Tillu’s story, like those of many other gangsters, goes back to their younger days, when they started off as friends in wrestling, says Mohit, a former wrestling champion himself.

However, Gogi and Tillu’s friendship curdled into deep animosity in the early 2010s, and their rivalry was sealed when they aligned with opposing camps during a students’ union election at a Delhi University college.

Both men also harboured aspirations of being Delhi’s biggest don and to fill the power vacuum that was created following gangster Neetu Dabodia’s killing in 2013 and the arrest of another prolific criminal, Neeraj Bawana, in 2015.

Mohit recalls how the two would face-off in testosterone-fuelled displays.

“Once, when Gogi had come out of jail, he and Tillu parked their cars facing each other in the middle of the market. This went on for hours. Both were unrelenting,” he says. I don’t remember who won in the end.”

On the night that Gogi was killed by the Tillu gang’s men, both Alipur and Tajpur turned into a fortress with heavy police deployment to maintain law and order.

Just like politics, the northern underworld— spread across Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab — also operates through interconnected networks. Some are friendships that started during sports training and student politics, and others are alliances formed in jail and to survive conflicts with common enemies.

For instance, Lawrence Bishnoi, the alleged mastermind of Moosewala’s murder, met his close associates Sampat Nehra and Kala Rana during sports training at Panjab University grounds. Later, in prison, Bishnoi forged an alliance with the Kala Jathedi gang.

The nexus now has over 700 members and associates like Kapil Sangwan alias Nandu (who is absconding) and handlers such as Goldy Brar (currently suspected to be in the US). Gogi was also in alliance with this nexus, and criminal Rohit Moi is emerging as its new leader, police sources say.

The other major rival syndicate is the Lucky Patial-Bambiha-Kaushal alliance, which includes the Tillu and the Neeraj Bawana gangs. Patial is suspected to be in Armenia while Punjab-based Devender Bambiha was shot dead by police in 2016. After Moosewala’s murder, both these gangs reportedly made social media threats to one another.

Financing the gang life

A central theme of the gang economy is what they call “finance” – a euphemism for extortion, property arbitrage, and harassing businesses to give protection money.

“Finance keeps the ship afloat. Without it, the ship sinks,” says Zahid.

Pressed further, he reveals the contours of “finance”. For most gangs, this involves settling property disputes in their area of influence. This could relate to land for commercial, agricultural, or residential use.

“Say there are two parties involved and they both claim a piece of land. The dispute has been running for many years. We get involved, get the matter resolved, and then take a cut from the parties for it,” he explains.

Hafta or protection money is another revenue stream, Mohit adds. If there is a business house operating in the area, say a manufacturing unit, the gangs take a certain fixed amount at the end or beginning of every month.

Apart from “finance”, the gangs also are heavily involved with gambling—both during sporting events, and via a book system. The book system is essentially like a lottery, which involves multiple criminals placing bets on numbers, across a vast network of operators. The final winner and outcome is picked by one party, they explain.

“During any big sporting events such as cricket matches, gangs also place odds-based bets through bookies,” says Zahid.

For all gangs and syndicates, money is the only ideology. It is all that matters, a police source tells ThePrint.

“In most cases, victims out of fear don’t even complain against these gangs harassing them for money,” another police source says.

Peering from his balcony, Zahid points out locations where drugs are peddled, occasionally glancing at his phone to monitor his CCTV feeds.

Keen to progress with his evening, he answers a phone call and abruptly moves towards the main gate. In parting, he says: “Let me know, I can get you to meet any gangster.”

(Edited by Smriti Sinha)

Also read: Networks made in jail to legal hurdles — 5 reasons Punjab gangsters are a step ahead of police