Sonipat: Areena wakes up before dawn, the first in the family to rise. She leaves the two-room house to visit the temple and feed her cow, before returning to prepare meals for their family of five. Her husband Balraj works at his juice shop supplied by the carrots, sugarcane, bananas, and beetroots grown in small quantities on their small 6 bigha farm.

As one enters their home, framed photographs adorn the exposed brick walls of their living room, depicting three generations. At one corner of the living room sits an old TV set Areena received as a wedding present 24 years ago. An object of envy then, it is now outdated. A fridge procured from savings is placed next to the mandir.

When guests visit, their son Rohit steps onto a rickety wooden stool to carefully insert a light bulb into the fixture to illuminate the room, reverently removing it later.

Rising costs, delayed compensation, and poor crop prices have forced most small and marginalised farmers like them to seek secondary incomes.

Farming, which once brought fulfilment, has become a profoundly discouraging vocation. “It’s just losses over losses,” Areena sighs.

Their story is also that of millions of marginalised Indian farmers caught in the quicksand of eroding agricultural viability.

This cautionary tale of agrarian distress is now firmly in the political spotlight. After securing a third term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first official act was to release the 17th instalment of the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme. Following delays in the release of the 16th and 17th instalments, by a month and three months respectively, Modi released the 17th instalment amounting to Rs 20,000 crore in Varanasi on 18 June.

This was estimated to aid as many as 9.2 crore farmers.

Under the scheme, launched in 2018, eligible families receive Rs 6,000 per annum in three instalments of Rs 2,000 each through Direct Benefit Transfer every four months. Its aim was to help small and marginalised farmers “ensure proper crop health and appropriate yields, commensurate with the anticipated farm income at the end of each crop cycle”.

In Haryana, the 17th instalment meant disbursement of a total amount of Rs 335 crore to 15,59,807 farmers in the state. A total of Rs 5,693.59 crore has been distributed in Haryana under the scheme to date, it is learnt.

According to the data published on pmkisan.gov.in, Haryana has as many as 19,88,431 verified beneficiaries. Of these, as many as 80,230 are in Sonipat alone.

The consistent increase in the number of beneficiaries in the state since 2019 was followed by a sudden decline in 2023. One reason for this decline, Wazir Singh, deputy director (Agriculture & Farmers Welfare Department), Karnal, told ThePrint, was that “under the e-KYC, Aadhaar card was made mandatory to avail funds from the scheme”.

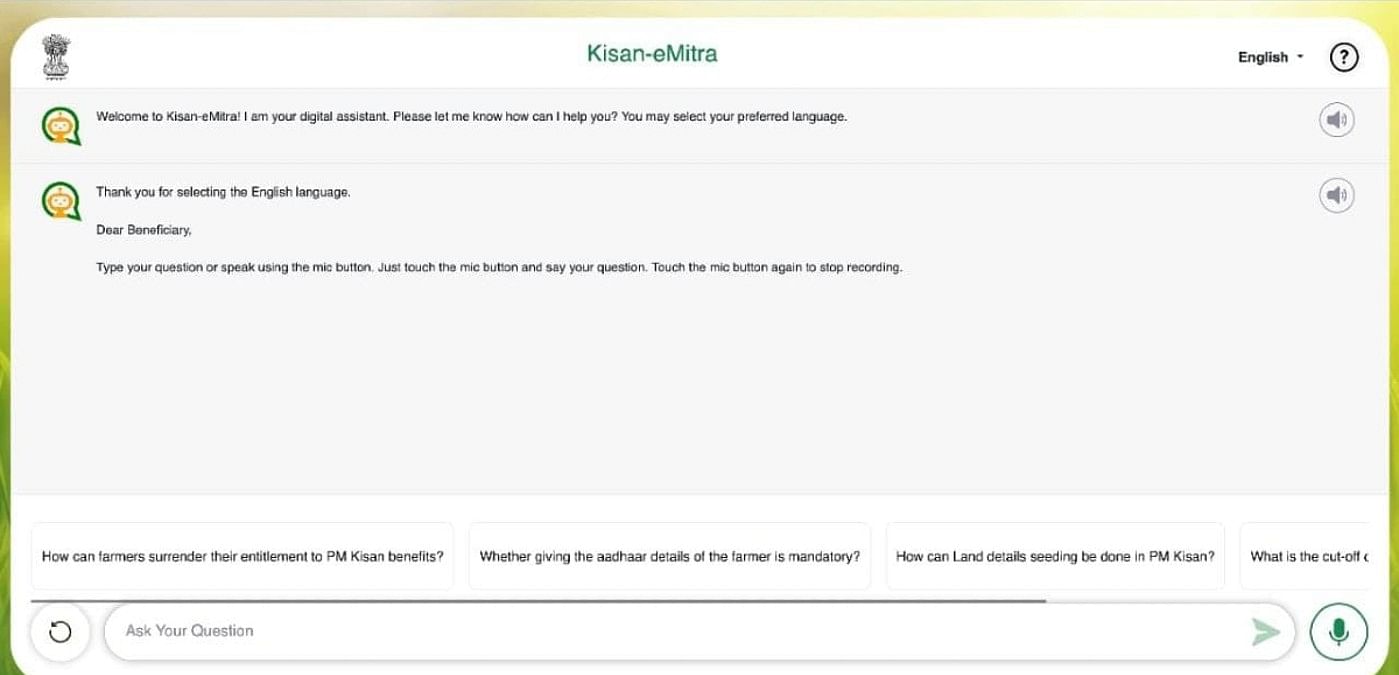

But that is not the only issue beneficiaries face. They want the government to increase the assistance given to them under the scheme and ensure timely disbursements. Another issue is the exclusionary nature of the Kisan-Mitra Chatbot launched on 22 September last year.

An AI-powered service available in 11 languages, the idea was to assist farmers. But despite its multilingual capabilities, the text-based nature of the service inadvertently excludes a substantial portion of its intended beneficiaries — illiterate and semi-literate farmers.

Also Read: Marginal farmers consistently lost over 50% crops in past 5 yrs due to extreme climate conditions

Unstable prices, wrath of nature & middlemen

For Areena and Balraj, their major crops are wheat and rice, sold at the mandi in Narela. Before they took on this farm on lease, their self-owned land was acquired by the state government for Rs 12 lakh in 2012 for construction of Rajiv Gandhi Education City.

The family on its small parcel of land grows 25 quintals each of rice and wheat every year. The Minimum Support Price (MSP) for wheat is Rs 2,275/quintal and for rice Rs 2,183/quintal.

But despite back-breaking work tending the fields each day, yields are barely enough to sustain them. “Ek tukda zameen se kya hoga?” asks Areena. (what will we get from this small piece of land?).

According to her, the price for yield fluctuates throughout the year dropping even to Rs 1,500/quintal if grains are not up to the mark. And even for grains that meet Fair Average Quality (FAQ) benchmarks, there is no guarantee they will be bought at the full MSP rate.

To add to that, unpredictable weather patterns damaged up to five rounds of cotton harvests, yet the family received no compensation or means to protect fields from pest attacks.

Paltry farm incomes meant the debt burden only swelled each season, with accumulated interest rates of at least 4-5 percent.

They also had to pay exorbitant prices for urea fertiliser and pesticides, which middlemen bundled forcefully with useless medicines to drive up profits.

A single seasonal purchase of such inputs, says Areena, could cost up to Rs 20,000.

With profitability a distant dream, the family hoped assistance would come from the government in the form of adequate crop prices that reflect their hard labour, subsidies for essentials, and their children’s education.

‘Ye doobte tinke ka sahara toh hai’

With an acre of land to his name, Kamal is another beneficiary of the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme. He also owns a tea/coffee and sandwich shop.

Sitting hunched over the counter, calculating monthly hisab, he explains using his handheld calculator how with a family of 12, a single instalment of Rs 2,000 comes down to Rs 66 per day and Rs 5 per person.

To avail of the scheme, his father goes to the nearest bank which is in Rai, Sonipat, where they have an account with Punjab National Bank.

Having sown jowar on his field on 7 June, he expresses disappointment with the fact that agriculture alone is not enough to sustain a family and hence the need for a ‘side business’.

Asked about the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme, he says: “Ye doobte tinke ka sahara toh hai.” (at least it’s as much help as a sinking straw)

Kamal and his father also praise the scheme for directly giving money by cutting out middlemen. In the past, they would have to go to the Sarpanch to avail of the benefit of any scheme.

Kamal went to the farmer’s protest both times but believes the 17th instalment by the Modi government ahead of the Haryana state elections is without any ulterior motives. “PM Modi achhe hai, bas unke aadmi neeche paise khaate hain toh humein nahin milta” (PM Modi is nice, it’s just that those under him are corrupt and that’s why we don’t get benefits)

Amar Sharma, 26, from Giwan Nagar is also a beneficiary of the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi scheme.

He complains of not receiving instalments for the last 6-8 months and the amount of the scheme being too low — “Rs 2,000 se ab ghar kaise chal sakta hai?”. (how can I run a home with Rs 2,000)

Amar, who frequents the weekly Sonipat Sabzi and Anaj Mandi to sell his produce, hasn’t heard of the Chatbot. Asked about it, he proclaims “Hum itne padhe-likhe nahin hain, ki usse baat kar sake”. (I am not educated enough to be able to talk to the chatbot)

‘Everyone eats from the same plate’

As the gentle breeze rustles through the wheat fields of Sonipat, the annadatta of Haryana holds the power to shape the region’s political landscape. MSP and agricultural reforms were pivotal issues ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha polls but the dire state of marginalised farmers remains unchanged.

Areena had participated enthusiastically in the previous farmers’ protests, even going to the Singhu border for 13 months on their tractor to deliver supplies. The peaceful demonstrations had raised hopes. But she felt disheartened now that three years on, the protests failed to spur substantive reforms, making her regret the time she invested in it. With pressing demands at home and farm, she was reluctant to participate again.

“The work used to suffer and yet nothing was achieved,” she laments.

Though the desire for change still stirred within her, the wider belief that all political parties were complicit in ignoring agrarian distress had also taken root. “Everyone eats from the same plate,” she remarks pithily.

If their farm incomes were to improve someday, Areena dreamed of renovating parts of their home. It was a simple desire — to live in dignified dwellings that reflected the hard work and essential societal role fulfilled by farming families like theirs over generations.

As dusk falls over the parched fields, Balraj and Areena retire to their modest home, exhausted from another day of toiling on their farm. Yet they find strength in each other to face another gruelling dawn.

Gauri Malhotra is an intern with ThePrint

Also Read: MSP, subsidies are at root of Punjab’s farm crises but its farmers are fighting to keep them