The future of work is changing quick. Our planet is in trouble. Education reforms are slow. Is autonomous learning in these wicked times a part of the solution? 21st-century researchers have understood that learning happens best when the learner is self-directed and connections are formed. Authentic learning, situated learning, informal learning, experiential learning, and collaborative inquiry are all examples of this approach in action.

Slowly but surely, there have mushroomed several learning environments in the world that support autonomous learning like the Sudbury Valley School in the United States, Swaraj University in India, or Agora School in the Netherlands, where students decide what to do with their time and learn based on needs rather than through classes or a standard curriculum. There are coaches, mentors, resources, and experiences made available to facilitate the breadth and depth of learning. The key difference is instead of the institution deciding ‘this is what you must learn’ and ‘this is how you must learn it’, the institution is partnering with learners and (g)local communities to meet individual and collective needs through robust and agile structures.

Don’t be afraid—knowledge is being shared, skills are being built, mastery is being achieved, learners are thriving in universities and at work, and learning is continuing beyond schooling and university age. A number of those who have had the freedom to listen to their inner voices and space to experiment and fail have gone on to do great work for a better world.

The future of learning is here. This is it.

Here are four questions or transformations I’ve been thinking about and believe that every student, teacher, educator, parent, administrator, and policy maker should ponder.

1. Why learn?

We all have different reasons to learn, and being human, we are always learning. It’s why machine learning is coupled with artificial intelligence. Among the top motivations to learn something are:

- Vocational / career relevance

- Gender, class, culture, race, family norms

- Natural desire to find meaning / self-fulfillment

- Personal relevance / Improve quality of life (e.g. health)

- Opportunity to increase capital (social, economic, cultural)

- Meeting shared goals

Whichever way you look at it, we learn to meet needs.

If you look into the roots of the word education you’ll find that the use of the word came about in 14th century France to mean ‘childrearing’ and ‘the training of animals’. Around 1610, it came to use in English to mean ‘systematic schooling and training for work’. This remains the active meaning of education today. We go from primary to secondary, then college, and some of us to university before entering the job market. At each stage of this process we are assessed and labelled as a success or failure. Post education, the ultimate benchmark for success and failure in society is usually profit or financial reward.

But the needs of the 21st-century human life are not only related to work and employment and profit making. They are much more nuanced and depend on individual, community, national, and international priorities. We live in an interdependent world after all. Why we must learn is about the same as asking what our current layers of needs are.

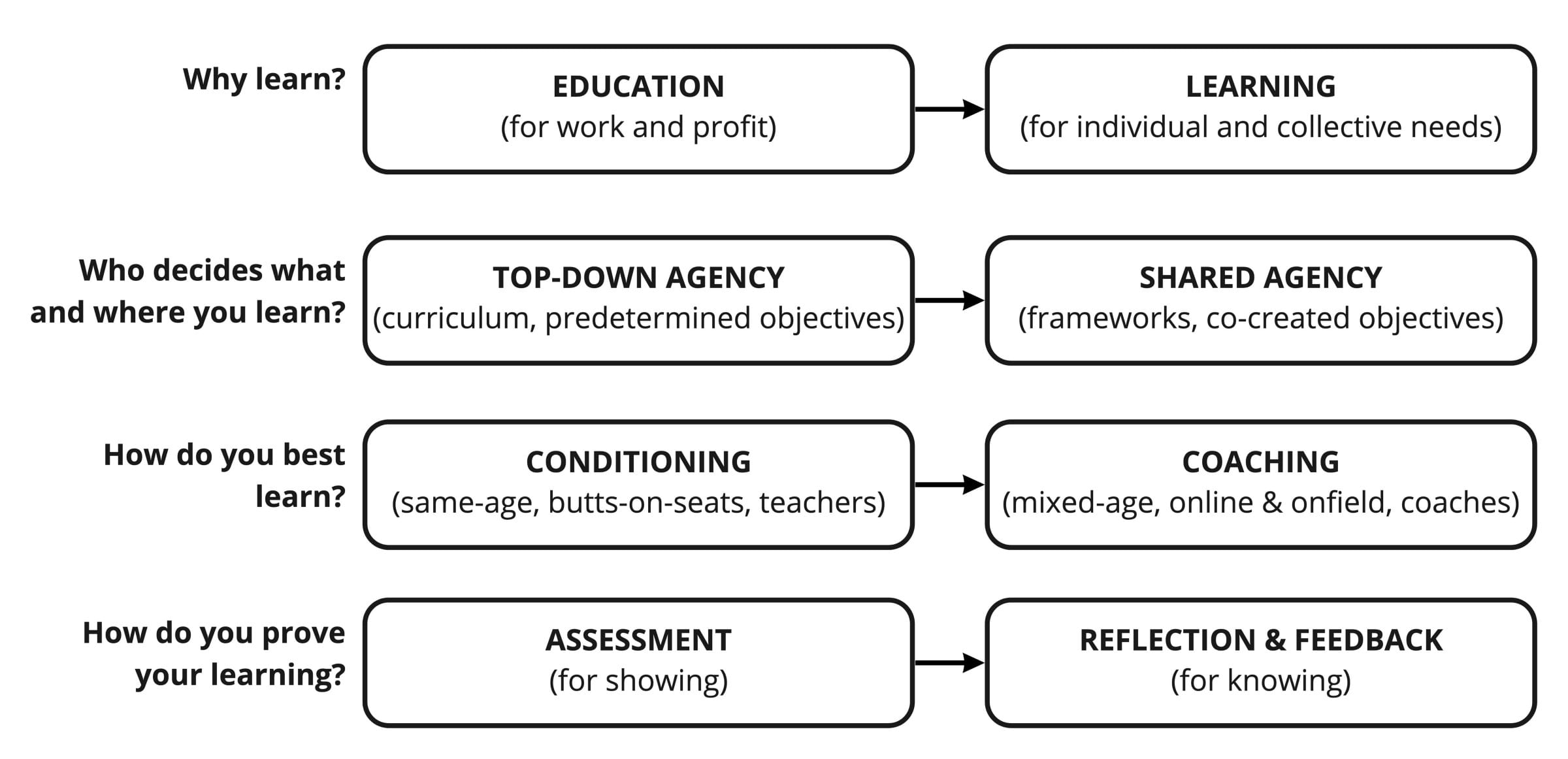

The first transformation is questioning why we learn — do we want to go beyond work and profit? Should we be humanists?

Also read: HRD works on big-ticket higher-education reforms to keep them ready for new govt

2. Who decides what and where you learn?

This question cannot be disconnected from ‘why learn’ as it depends on the needs and motivations to learn. Every individual and society has different needs, but curriculum seems to be decided at a national level. What’s worse, if you are from a colonized land, it’s not even your peoples who have decided what you learn. Most probably, your curriculum comes from the Global North, and it hasn’t been changed much. (Note: The North South divide is broadly considered a socio-economic and political divide. All the G8 countries are from the Global North who also set the general development and economic agendas.)

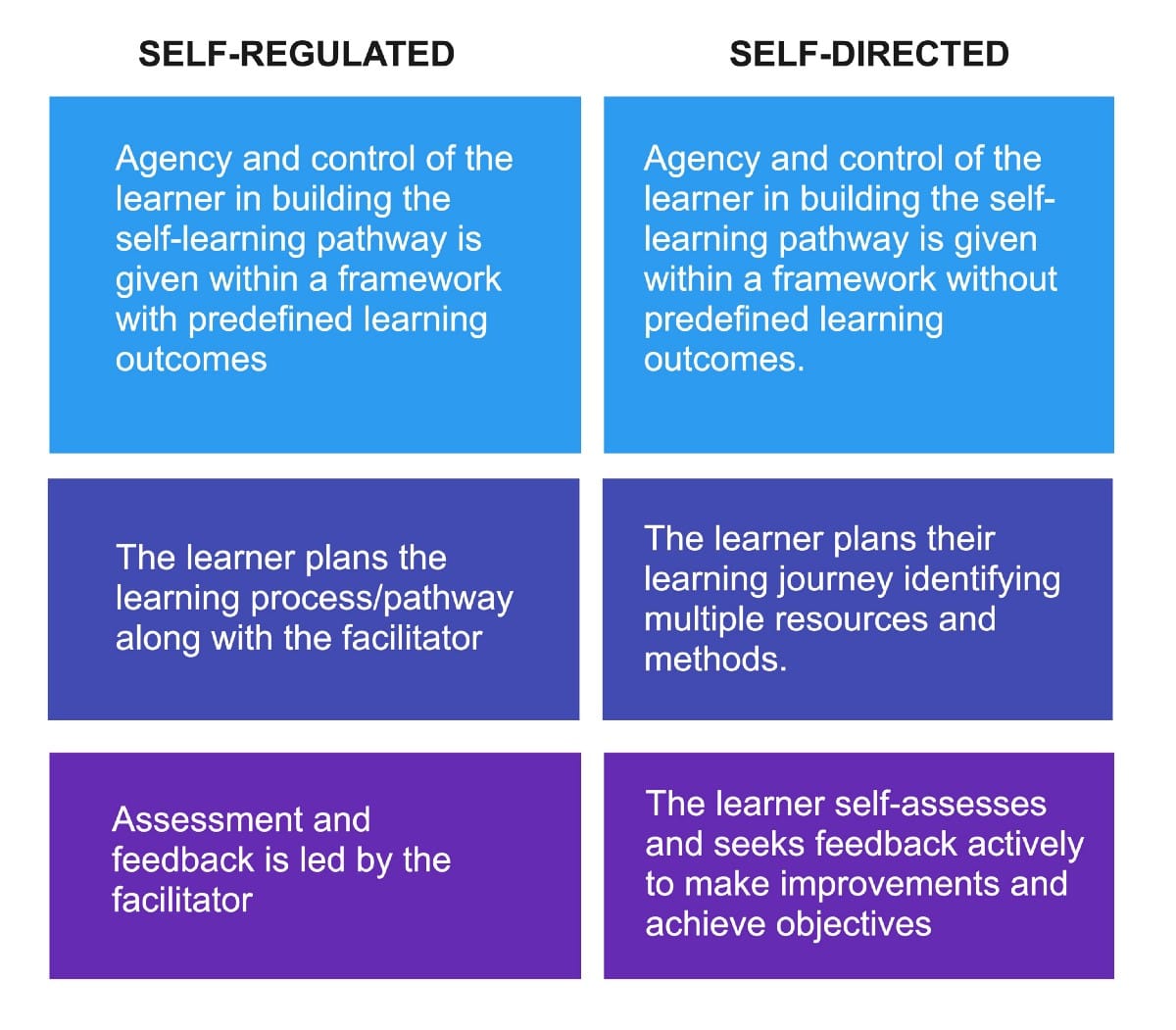

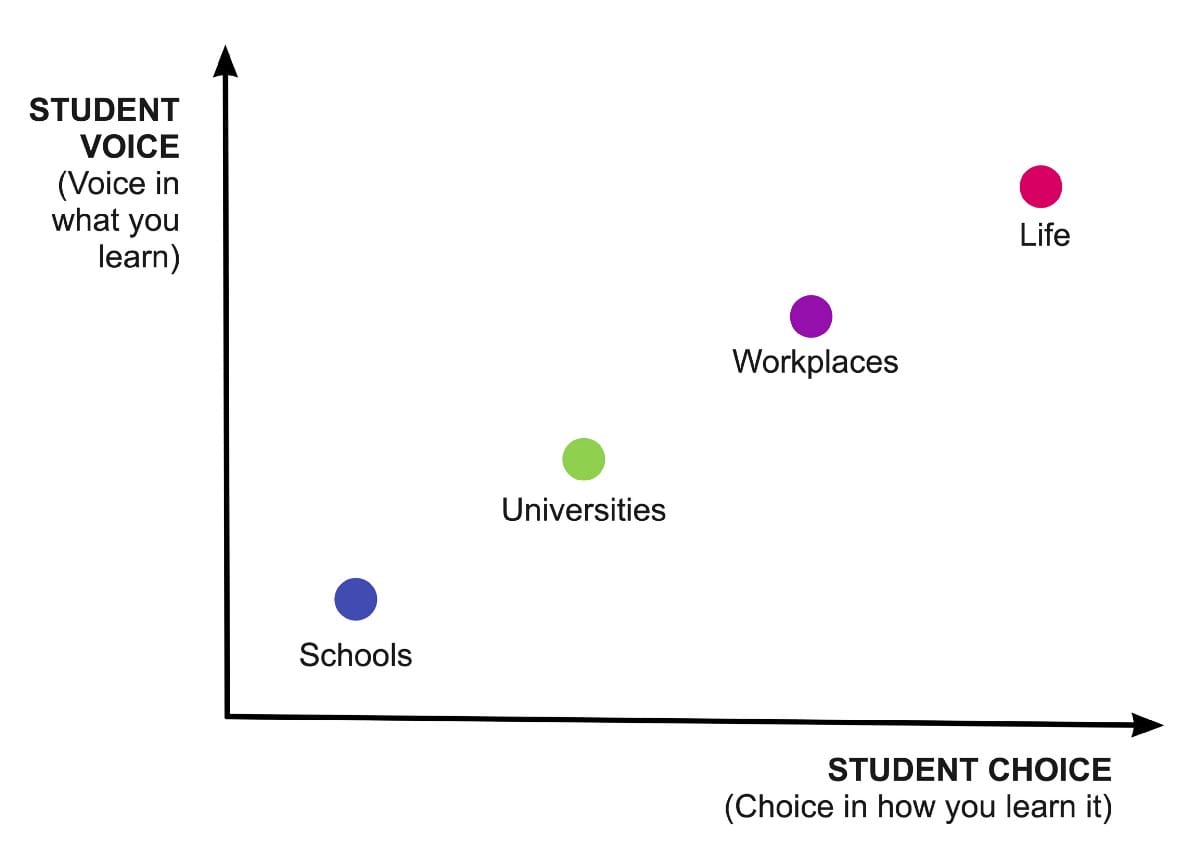

I teach at a United World College — a network of 17 schools around the world educating for peace and a sustainable future. The high school I teach at, UWC ISAK Japan, follows the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program (IBDP). The IBDP program supports constructivist pedagogy — student-centered and self-regulated learning. This gives more freedom in how you learn. But what you learn is still controlled by curricula decided by people at least four degrees away, or dead. Given its mission, learning here is more than just IBDP, and through programs such as transformational leadership, clubs and activities, outdoor education, residential life, and short courses, students get many more opportunities to exercise their choice, but exercising their voice still needs some work (self-directed learning). (Note: ‘Student voice’ refers to students being able to influence what they learn through policies, programs, contexts and principles).

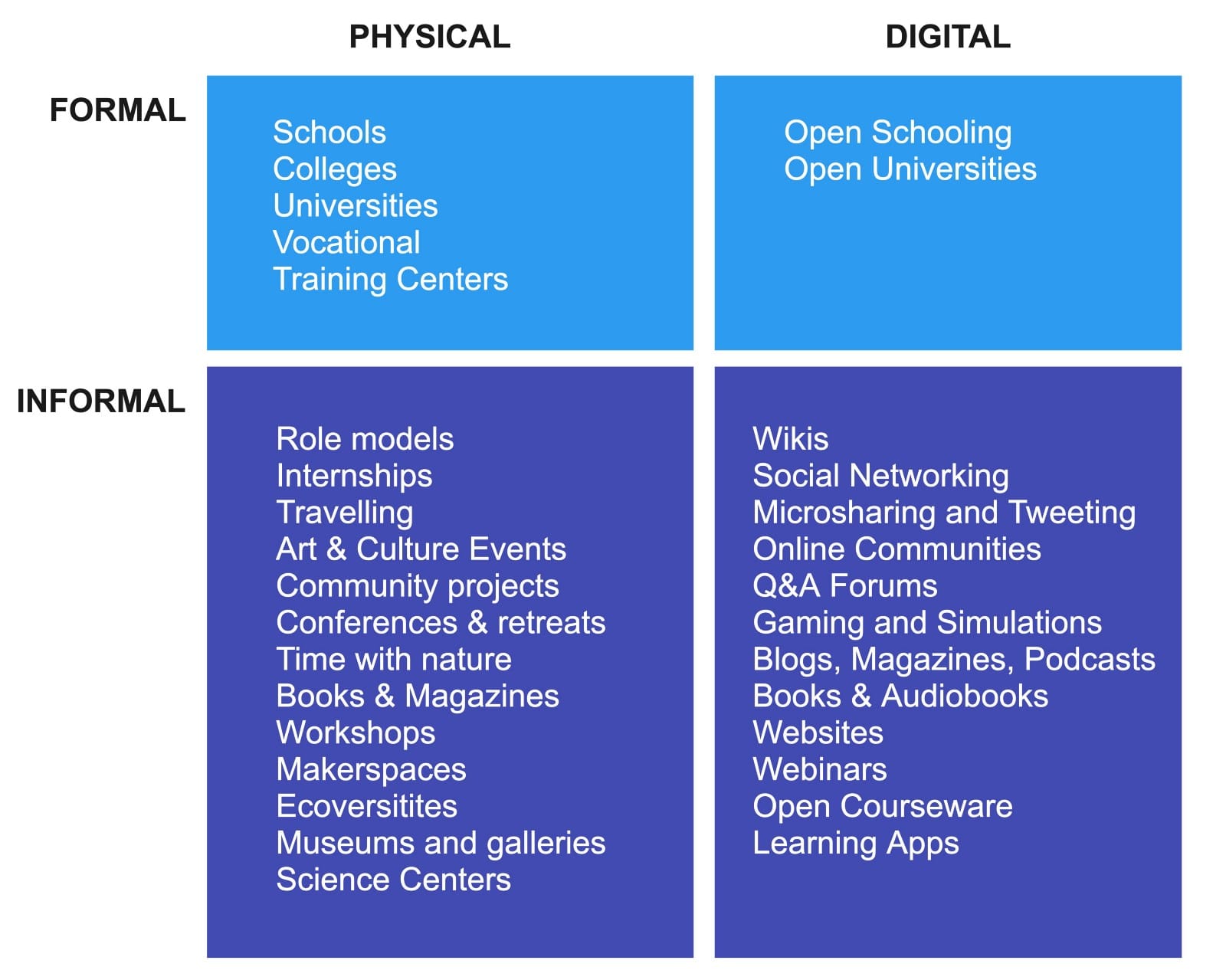

I also run a series of interdisciplinary, informal learning festivals with a collective called The Story Of in India. We take broad themes like Light, Space, and Mind, and invite artists, scientists, philosophers, educators, and cultural practitioners to interpret them from multiple perspectives into stories that burst out into learning opportunities for a city wide audience. Through generative processes we hone in on what we want to learn and how we want to learn it. It’s a wild ride(take a look). The reason I am so attracted to informal learning is the freedom to determine the learning goal (what am I learning) and play with the where.

Learning was never meant to be restricted to schools, colleges, and universities as the custodians. It just became that way — the same way that temples and churches and mosques became the custodians of our spiritual life — and the same way businesses became the custodians of our economic life. Learning happens everywhere and the world of informal learning is only growing in these technological times.

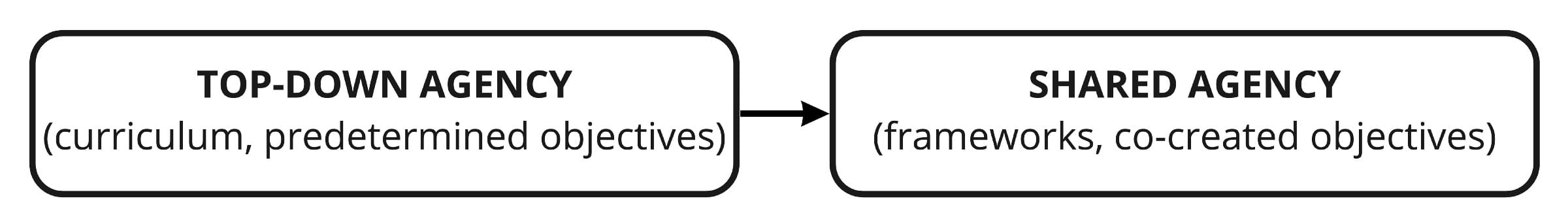

The second transformation is to question who decides what you learn? Who is the director of your learning goals and outcomes? Should it be the nation, institution, community, self, or co-created. I advocate for shared agency, with each learning institution building generative processes for what their learning framework should look like, rather than adopting a top-down curriculum that has little connection to on-ground needs.

Also read: Govt plans higher education revamp — study at one university, get your degree from another

3. How do you learn best?

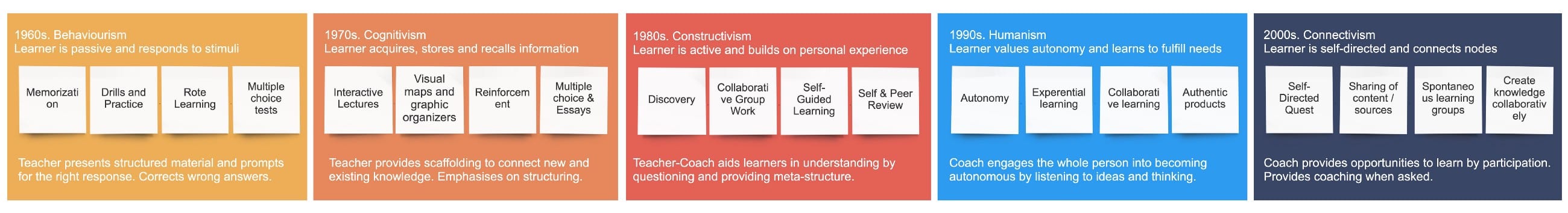

At the beginning of the 21st century, researchers understood that learning happens best when the learner is self-directed and connections are formed. While the theories have evolved, the practice has not.

In India our education systems are still 30–40 years behind. Some schools, colleges, and universities are still very into rote learning, drills, and reward and punishment, while more progressive ones are implementing constructivist learning theories. Informal learning environments are considered to be the most in line with the latest theories of humanism and connectivism, where the learner is self-directed, driven by personal needs, interests, and motivations, and finds the way. A study on workplaces indicated only 10% of learning happens through formal training and 90% happens through informal methods.

The third transformation is to question the tactics of learning, once we have the vision (why learn) and strategies (who decides) in place. Research points to the following eight conditions under which we learn best.

- Self-directed motivation / Meeting needs

- Freedom within a framework / Play / Experimental practice

- Safe spaces / Empathetic listening / Coaching for support

- Mentorship for depth

- Opportunity for connections

- Reflection points and places (e.g., through coaching and facilitation, Informal conversations)

- Mixed-age learning

- Shared motivation in collective of learners

How can educators and learners make more opportunities for these conditions to arise?

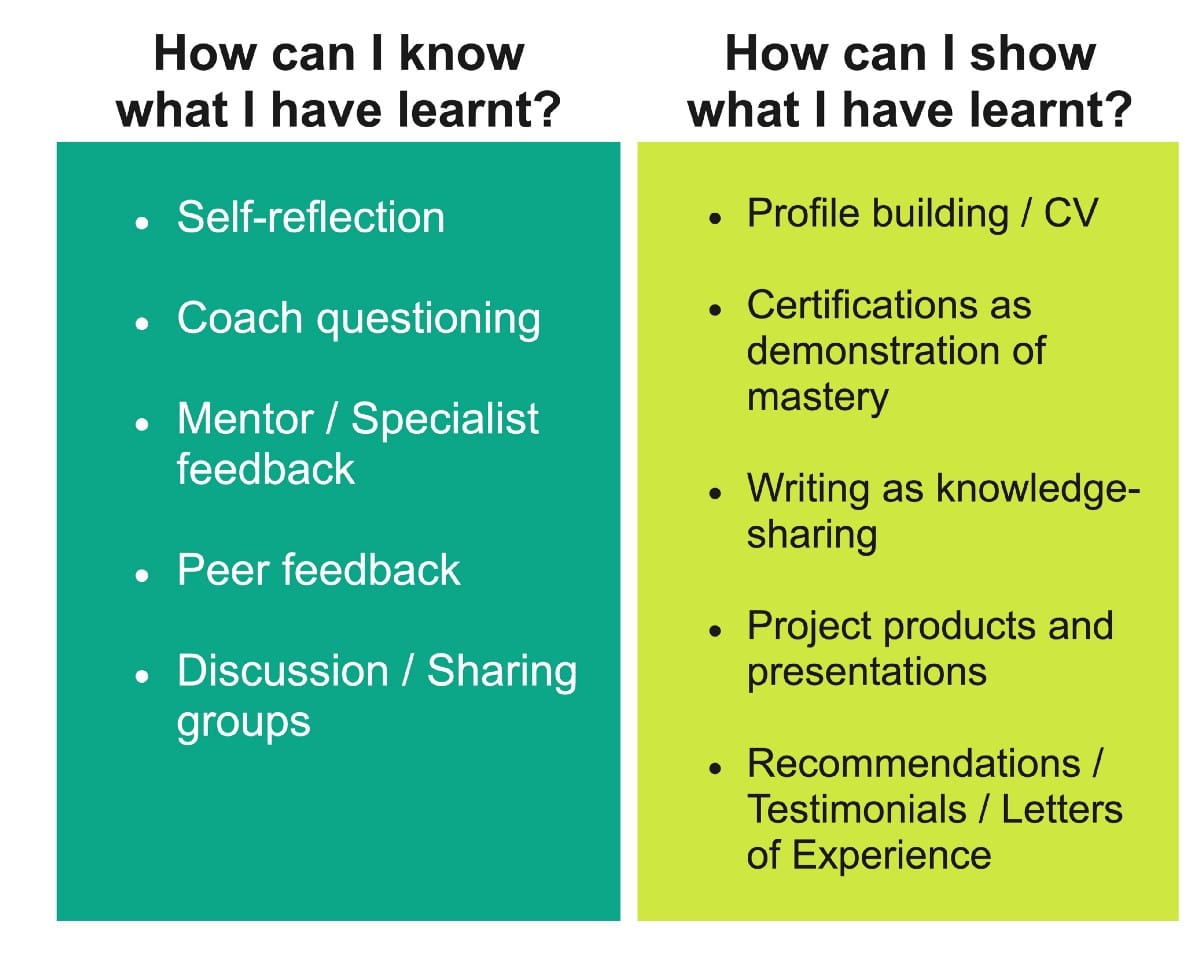

4. How do you prove what you have learnt?

The first question is who do you need to prove it to: yourself or others? Assessment can broadly be divided into how do I know I have learnt and to what level and how can someone else know I have learnt and to what level? The reasons for the former are obvious. It is important to know what you know so as to have better self-awareness of where you are at to determine where you should go, and how you should communicate your learnings based on the next stage.

The reasons to show you have learnt really depends on your need to learn. If you have learnt something for vocational or career relevance, job markets are competitive and there needs to be a way to distinguish you from another human (norm-referenced assessment). If you have learnt something for a natural desire to find meaning, then the assessment is confirmation of finding meaning or coming closer to it (confirmative assessment)? If you want to enrol into a university to increase your capital, to play on a level playing ground, you need to be referenced to certain criteria for entrance (criterion-referenced assessment).

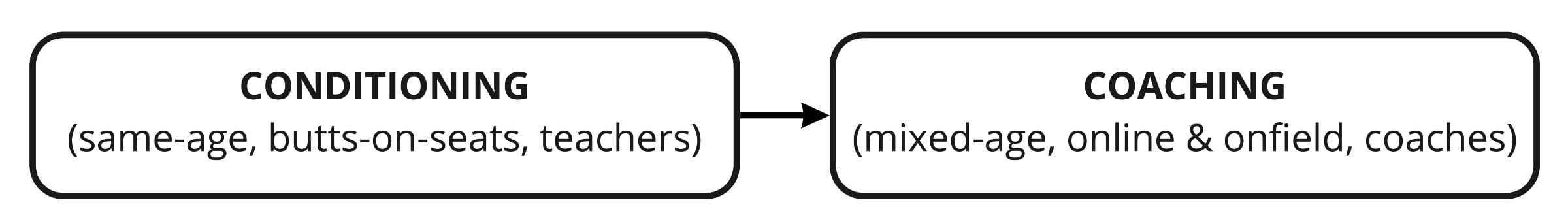

In high schools the world over, students are living with the paradox where research says that students need to develop 21st century skills like creativity, citizenship, entrepreneurship, collaboration, and compassion to thrive — skills that are difficult to count because there are no ‘right’ answers — but they are measured on right/wrong criteria through traditional exams stuck in counting methodologies. At UWC ISAK Japan, while the UWC curriculum (IBDP + Leadership + Residential + Clubs&Activities + Outdoor Ed) is holistic, it’s also overwhelming. At the end of the two year experience, students produce a portfolio and write exams — the latter looks the same kind of sad that it did for me exactly 20 years ago.

Exams, points, and grades remain important because they are the dominant criteria for students to secure entry into a university of choice — and the scholarship depends on the grade. But wait a minute, progressive universities are well aware that 21st century skills are difficult to count and have evolved their admission procedures to include portfolio assessments, interviews, and auditions, and mastery certifications. Khan Academy has a great article on how universities have evolved to accept the homeschooled (autonomous, self-directed learners).

The fourth transformation is to question the status quo of assessment and deprioritize assessment for showing because it is only applicable in one case: entrance to university. Workplaces don’t really look at grades and marks. They are more interested in a certification of completion, the reputation of the university, your CV (CV= curriculum vitae, a list of statements of what you have learnt through school and experience), and testimonials of skills and attitudes. And university admissions are changing. Assessment for knowing what you know and to what level remain valuable — but isn’t that just reflection and feedback?

What’s Next?

Acknowledgements to Michael Fitzgerald from Edith Cowan University and Cary Reid from UWC for their helpful coaching in reaching this somewhat lucid flow. The next challenging question is what is the most efficient path for top-down education to transform into autonomous, agile learning frameworks? This is going to be the main focus of a PhD proposal I am currently working on — yup, I am taking the leap! These four transformations shall serve as my guide and I hope it can serve as yours as well if you are thinking about how systems of education and learning should transform.

This article was originally published in Medium.com. Read the original piece here.

Also read: Rahul Gandhi’s interest-free education loan can’t help much if banks are student-unfriendly

This should be the most hot topic to discuss, there are lots of research , lots of problems in the education system and rule implications are already pointed out but what? Nothing changes.

Our citizens along with government should realise we have such huge human resource which are not used properly. Like advanced nations our education should be more work based, vocational training, internship based!! Youths here either loosening their prime (18 to 28 ) reading, or in dipression or playing pubg. Here, i would like to draw the education systems of Germany and Japan, i think today India need to give more emphasis on discipline learning and vocational education and use of the human resource properly.

Very well written. I feel children have evolved and schools and curriculum have not.

The government has to stop taking blanket decisions on education. In India, there is a wide gap in the levels based on economic background. The government has to acknowledge the difference and do the needful accordingly.

Bhai school kab khul raha hai