Orchha, Chhattisgarh: It’s Sunday. The noon sun is shining down as the sounds of children playing football trickle into a portacabin classroom made of bamboo.

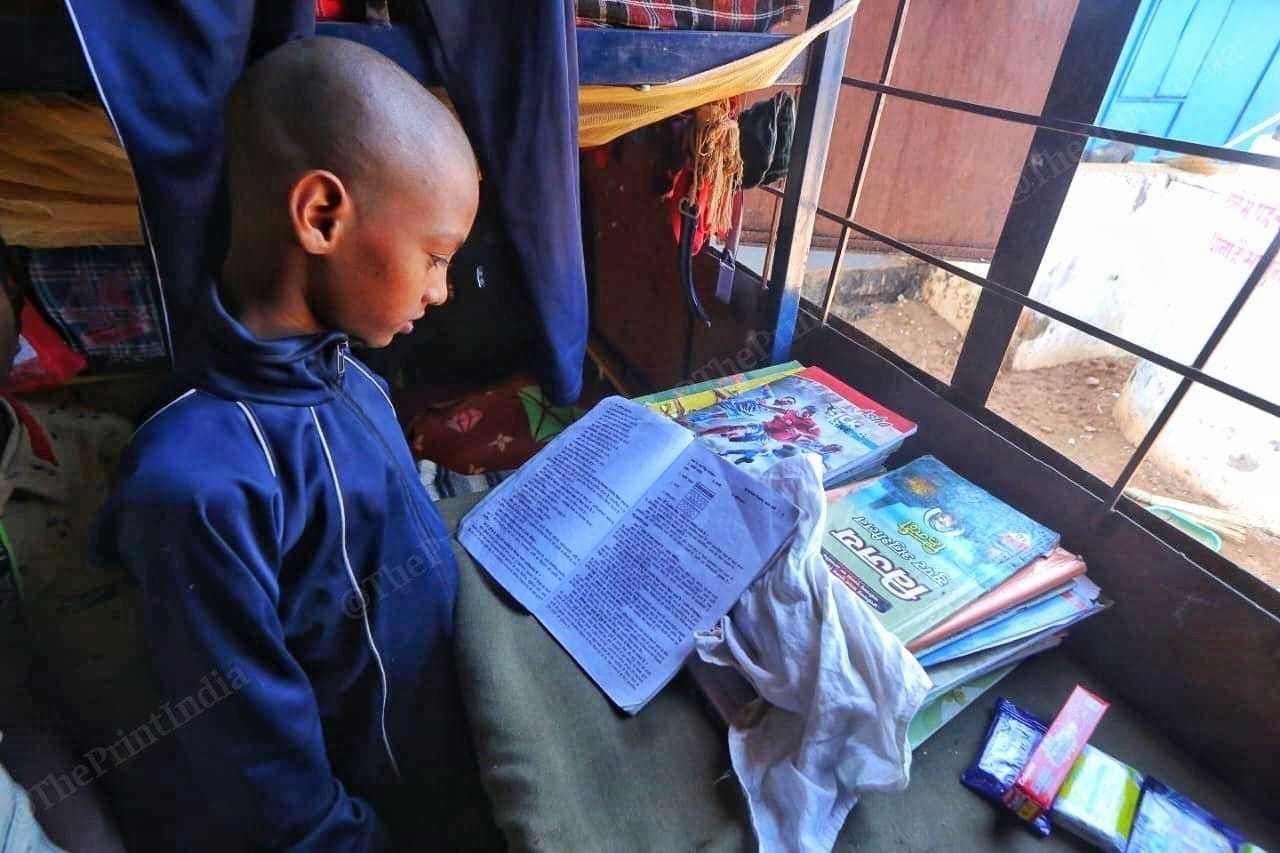

Fourteen-year-old Rinku Kumar sits poring over his biology textbook, oblivious to the squeals and laughter outside. On the page open in front of him, is a diagram of a human heart.

Rinku lives in Kongera village in Chhattisgarh’s Bastar — a place where healthcare is non-existent. He says he wants to become an “all-round doctor, who is accessible, knows the human body well, and can cure anyone”.

The idea struck him at age 7, when he saw his older brother and some friends die of an illness that went undiagnosed due to poor access to healthcare. Other villagers pinned the deaths on a “curse” and moved on. But Rinku couldn’t.

Today, he is one of 570 boys studying in a portacabin school (there are other such schools for girls too) at Orchha, a village in Narayanpur district. Run by the Bhupesh Baghel-led state government, the ‘Orchha Porta Cabin Awasiya Vidyalaya’ — a series of portacabin structures grouped together — caters to children from the remote villages around Abujmarh, a densely forested Naxal area with little to no connectivity.

Started in 2012, the portacabin schools initiative is aimed at providing education to the state’s tribal communities, mostly Gonds and Halbis. No fee is charged by these schools.

In a state grappling with left-wing extremism, poor road connectivity, and inadequate education facilities, these residential schools, which have classes from grades 1 to 10, come as a relief.

The idea behind the initiative is to make education accessible, not only in areas where schools were once destroyed in Naxal violence but also to tribal children living in remote areas of the state, Narayanpur collector Ajeet Vasant tells ThePrint.

There are two such schools are in the district. The one at Orchha opened in 2013.

“Earlier, schools were located in remote places where there was no electricity, few teachers, and where students had to walk for miles for education. Here we bring them all together so that they don’t have to care about anything, including food and clothes, and can just focus on their studies,” Vasant says.

The schools follow the State Council of Educational Research and Training (SCERT) curriculum and all of the school staff — from teachers and hostel wardens to cooks and sanitation workers — are recruited by the state education department.

The schools have both permanent staff and ad-hoc appointees, and for students like Rinku, they provide an opportunity for a better life.

“Our people live in villages where there are no doctors. So many people fall sick but no one knows what has happened to them,” he says. “They are just put in sheds and then they die. I want to be a doctor so I can help my people live more. That is why biology is my favourite subject.”

Also Read: Adivasi identity, ST status, politics — what’s fuelling anti-Christian attacks in Chhattisgarh

Treacherous paths

It’s a challenging task to get students to school. For this, teachers and local volunteers walk treacherous paths that involve hiking and crossing rivers. Their journey from village to remote village could take days.

And then there is the task of convincing parents, most of whom are farmers.

“These are volunteers who know Gondi and Halbi. We visit the villages and educate the parents about the merits of the portacabin schools for their children,” says Ram Kishore Kurram, warden at the Orchha school, while speaking to ThePrint.

He adds: “We’re also in regular touch with various anganwadi workers who tell us about villages that have kids of school-going age. So we chart out a plan to visit those villages. We also tell parents who come to drop off their children to spread the word.”

Although the medium of instruction is Hindi, lessons are also conducted in Muria — the language of the local tribes — for classes 1 through 3.

“Most children have no knowledge of Hindi, so from class 1 to 3 we take classes in both Hindi and Muria, till they are comfortable with Hindi. But they pick up Hindi very quickly since they stay with children who know the language. By the time they reach Class 3, they know it well,” Tamesh Vike, a teacher at the Orchha school, tells ThePrint.

The schools help students prepare not just for higher education, but also for various competitive examinations.

“From Class 5 onwards, we train the children so that they can go to Eklavya, Navodaya Vidyalalayas, Ramakrishna Mission schools, or any other higher educational institutes. Our aim is to strengthen their basic foundation, inculcate interest in studies, and then they do the rest,” Pankaj Verma, who teaches science to middle school students, told ThePrint.

While Eklavya schools were started in 1997-98 to provide quality education to tribals in remote parts of the country, Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas are residential schools that cater predominantly to children of rural backgrounds.

The students come from underprivileged backgrounds and have a hunger for education and to make something of their lives, says Verma.

Like Rinku, many students want to be doctors and science remains a favourite subject. Therefore, the school is working on arranging for a science laboratory along with a television equipped with video conferencing and other communication features.

Participation in sports too is encouraged. “Many of our children have also been selected for state-level tournaments in kho-kho, kabaddi, volleyball, and cricket,” says Orchha school warden Kurram.

Giving back

Children take some time to get into the rhythm of school life but once they do, they settle in well, Kurram adds.

The day begins at 4 am when the children wake up for “study time”. After this, they assemble in the common hall — a tin shed right in the middle of the school — for prayers at 5 am.

Classes start at 9.45 am and go on till 3 pm.

“Then, after lunch and an hour’s rest, we get to play. There are several activities in the school and we all sleep by 10 pm because we have to have an early start to the day,” says Sohan Mandawi, a Class 10 student.

Saibo, another Class 10 student, is busy writing on the blackboard. A resident of Bhatbeda village, who’s been at the school since Class 3, he studies after class for exams in February so he can remain “at the top of his class”.

His village doesn’t have a school, roads, or electricity, but he’s determined to return there as a teacher.

“I’m lucky to be here and hence I want to take this opportunity to study and become a teacher so I can return to my village and teach the children there,” he says shyly. “Not everyone can come to these schools, but after I become a teacher, I can go from village to village to hold classes. That’s my dream.”

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Adivasis are not Hindus. Lazy colonial census gave them the label