Jodhpur/Ajmer/Jaipur: For Sania, Mansi, Monika, and Bushra, all first-generation learners, the school has been their gateway to a brighter future, which now has come under a dark cloud.

With three orders in January, the Bhajan Lal Sharma-led BJP government in Rajasthan set into motion the merger of 449 schools with larger, better-performing schools in their vicinity. The government cited low enrolment (fewer than 15 students under the Rajasthan government policy), separate schools on the same campus and schools close to each other among the reasons behind the move.

The move has sparked protests across the state, with strong opposition from parents, because it threatens to force children, mostly girls and those from underprivileged backgrounds to drop out.

A key point of contention—highlighted in the major protests in Jodhpur and Bikaner last week—is the merging of all-girls schools into co-ed institutes. Many parents fear this change could compromise their daughters’ safety and educational environment.

Other concerns include the increase in home-to-school distance for many students and changes in the medium of schools and cultural environment.

Not only the parents, former CM Ashok Gehlot has also condemned the move. BJP MLA Jethanand Vyas from Bikaner West has written to Education Minister Madan Dilawar, requesting an exemption for the girls’ school in his constituency.

The girls fear their parents will prevent them from continuing their education if the merger goes through, derailing their dreams.

“I’m more scared for my two younger sisters, who also study here,” Mansi (16) told ThePrint. “My parents allowed us to attend school because it was an all-girls institute close to home. They will never let us study with boys because of societal norms. There is no other all-girls government school around. I do not know if I will be able to finish my education. All I want is to study and, one day, go to college.”

The situation in Ajmer is quite different. In Anderkot, which has a significant population of Muslims, 12-year-old Neha is filled with anxiety as her 83-year-old Urdu-medium school is set to merge with a Hindi-medium school on the same campus.

“We have been studying in Urdu since first grade. Even my parents went to this school—they don’t know any other medium. They want us to continue in Urdu only. How will we cope with a sudden change? I do not know if I can continue my education,” she said to ThePrint.

Officials in the district education departments are aware of the concerns but assured that “no schools are being shut, they are simply being merged with better-performing schools”.

A senior official from Jaipur’s school education department, speaking on condition of anonymity, told ThePrint, “We have forwarded all complaints to our headquarters in Bikaner for review. We are hopeful for a positive outcome for our students.”

IAS Ashish Modi, the director of secondary education in Rajasthan, said the mergers will be implemented starting from the next academic session in July 2025.

“Out of the 260 upper primary and secondary schools, 200 had zero enrolment. The mergers are in line with RTE norms, and the senior secondary schools being merged share the same campus,” he told ThePrint.

“This move is aimed at expanding educational options for both boys and girls, allowing for a broader range of streams. We will ensure that girls do not drop out of school. Instructions have already been issued to schools to ensure the same,” Modi said.

Why schools are being merged

The school rationalisation project began in Rajasthan in 2014 under former CM Vasundhara Raje. By 2018, over 20,000 schools, including elementary and secondary schools, had been merged.

However, the approach shifted when the Congress government, led by Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot, took power in December 2018. According to official data, 606 elementary and 796 secondary schools, previously merged, were de-merged to improve student and teacher engagement.

Presently, Rajasthan has 70,233 government schools. Of them, 32,598 are primary schools.

School rationalisation is not limited to Rajasthan. It is happening in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Odisha, where smaller, low-enrolment schools are being merged with larger ones nearby. Resistance has emerged in several areas, including Himachal Pradesh’s Spiti, where parents protested last year after a local school was merged with one far away, citing difficult geography and harsh weather conditions, which made travel challenging for young students.

In 2017, the Ministry of Education issued guidelines for rationalising schools based on NITI Aayog’s feedback. While endorsing mergers, the guidelines stressed a need for flexibility, warning against a “one-size-fits-all” approach. They emphasised considering factors such as language, culture, and community consent and warned that merging boys’ and girls’ schools should only happen with community approval.

However, the recent merger orders by the Rajasthan government appear to violate these very recommendations.

Also Read: In rural India, 82.2% teens aged 14-16 know how to use smartphone but only 57% use it for studies

‘What’s our mistake?’

Several schools being merged are all-girls institutes, primarily serving marginalised communities and minority groups. None are low-enrolment or zero-enrolment schools but run on the same premises where co-ed schools run in another shift.

Jodhpur’s Government Girls Senior Secondary School in Siwanchi Gate and Pratap Nagar Girls’ Senior Secondary School are two such examples. Students and parents from these schools held protests from 22-25 January, demanding the decision be reversed. Videos of girls sitting atop a police vehicle in protest made the rounds on social media.

Similar mergers of all-girls schools are planned in Bikaner, Jhunjhunu, and Sawai Madhopur, among others.

Monika Kumari (13), enrolled in Jodhpur’s Siwanchi Gate School, hopes to be the first girl in her family to complete her education and become a teacher. The merger of her school threatens to shatter her dreams.

“My parents have always made it clear they will not let us continue our education if the school becomes co-ed. No one asked us, or our parents, before making this decision. Why can not this school continue as it has for the last 40 years? On the one hand, the government promotes ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’. On the other hand, it is making such abrupt decisions, which could destroy our futures. What is our mistake?” she asked.

“I have never studied in a co-ed school before, and I do not feel confident about studying with boys. I do not understand why they are putting us through so much stress,” said Benazir (12), who studies in Class 6 of the government girls’ senior secondary school in Jodhpur’s Pratap Nagar.

Around 5.30 pm last Monday, parents gathered outside the school to ensure their daughters’ school would not merge immediately.

“My two daughters are in Class 9 here. After Class 8, it took a lot of effort and fights with my husband and in-laws, who are opposed to sending girls to school after a certain age, to enrol them. I pick and drop them daily to ensure their safety. After the merger, they would not let them stay in school for a single day,” Babita, a parent, told ThePrint.

Officials at these schools have been taken aback, too. A senior official from Siwanchi Gate School told ThePrint that most girls in the school come from marginalised backgrounds, with their mothers working as domestic helpers and fathers doing low-wage jobs.

“Changing the mindset of parents overnight is not realistic. I believe co-ed education can benefit girls, helping them prepare to face the world. However, such a change should be only after broader consultation with the community,” the official said, requesting anonymity.

Siwanchi Gate School, with its 450 girls, will merge with another school with 1,000 students. “There are only 20 functional classrooms. How will 1,450 students fit in this space? If the merger happens, we will still run it in two shifts. What is the point?” the official questioned.

Pratap Nagar Girls’ School, with over 400 students, most from the cobbler community, faces similar issues. “After the merger announcement, several parents asked for transfer certificates. The nearest all-girls school is over five kilometres away. Most can not send their daughters there. Moreover, with 1,000 students, we have very few classrooms,” a teacher told ThePrint, requesting anonymity.

Change in medium of instruction

With their 200 and 75 students, two Urdu-medium schools in Ajmer’s Anderkot are to merge with a Hindi-medium school running from the same premises but in a different shift.

Sania, a Class 7 student from one of these schools, said, “If we wanted to study in Hindi medium, we would have chosen that from the start. Now, after studying in an Urdu-medium school from Class 1-7, how am I supposed to switch mediums suddenly? No one in my family can help with my studies,” she told ThePrint.

Speaking about her plans, she said, “Bahut kuch karna hai, madam. Mujhe Urdu ki teacher banna hai (I want to do a lot, madam. I want to become an Urdu teacher).”

Echoing her concerns, Bushra, a Class 8 student, said, “Urdu is not just the language of one community; it’s one of the constitutional languages. So why is our school being merged?”

Bushra’s and Sania’s school has been running since 1941, said a senior teacher at the school. “Rajasthan has very few Urdu-medium schools, and now, if these are merged, where will the Urdu teachers go? How will our students cope with this change? This decision is surprising, especially since the government is encouraging education in native languages,” the teacher told ThePrint.

The issue has also taken a political turn, with S.M. Akbar, a member of the minorities wing of the state Congress committee taking the matter up with the CM’s office. “This is a minority-dominated area, and many generations of families have studied in these schools. The abrupt decision to merge them has upset parents, who are concerned about their children’s medium of instruction being changed, and the prospect of sending their daughters to co-ed schools. We urge the government to reverse this decision promptly,” he told ThePrint.

Similarly, another school, Sindhi Delhi Gate School, is supposed to merge with a Hindi-medium school despite getting a brand-new building in the Kotra neighbourhood of Ajmer. The school has 275 students.

When ThePrint visited the school Wednesday, a senior teacher said that Sindhi was not used as a medium of instruction but remained a mandatory subject for classes 11 and 12. The idea was to preserve the language, the teacher said.

“If we merge with any school that doesn’t offer Sindhi, we can not make it mandatory. Sindhi is already an endangered language, and this merger could push it further towards extinction,” the teacher said, requesting anonymity.

The school has also informed the education department officials about the issue. “We are yet to hear back from them,” the teacher added.

Also Read: Budget boost for 5 youngest IITs with 6,500 additional seats, more infra; fellowships for all IITs

A long walk to school for young kids

In Jaipur’s New Sanjay Nagar, residents were taken aback by the recent merger order for a primary school serving students up to Class 5. Locals said the school’s original building was damaged by heavy rainfall before COVID-19 in 2019, forcing children to temporarily shift to another school—a kilometre away. The building was recently reconstructed after a lot of intervention and protests by locals. However, it is now locked and inaccessible to students.

The school has been merged with the senior secondary school in Rajeev Nagar where it was temporarily relocated, with the order saying that the two schools run on the same campus. For young children, the long walk to the school with heavy bags has become a struggle.

Iqra, after the original school building became dysfunctional, moved to a nearby school in Shastri Nagar. Since then, Iqra has been eagerly awaiting the day her school would open again.

“We used to visit the construction site every day last year, hoping to start classes in the new building. But now, they are saying we will be moved to Rajeev Nagar. I get so tired walking to school,” she said.

On Friday afternoon, Mamoona Begum, a resident, attempted to disperse a group of young children playing near a pile of garbage in Sanjay Nagar.

Speaking to ThePrint, she said many young kids in her locality no longer go to school. “Those enrolled in this school still attend classes, but 100-120 children, now three to four years of age, do not go. Their parents go to work and have no time to pick up and drop them from the other school, which is more than a kilometre away. They were hoping they would enrol once this building reopens,” she said.

Vipin Kumar, the state president of Rajasthan Prathamik and Madhyamik Teachers’ Association, raised concerns over the violation of the Right to Education (RTE) Act of 2009, mandating that a primary school be within one kilometre of every child.

He questioned, “When a new building is up, why is the government merging the school? It is a clear violation of students’ right to education. How will young children travel to a distant school?”

Kumar pointed out that when the government under Vasundhara Raje merged schools, it led to a significant increase in student dropouts. “The same will happen again. Students will refuse to attend due to the distance, and parents will eventually become weary. How can teachers then ensure students’ regular attendance?” he asked.

The state government’s order to merge Deen Dyal Upadhayay Government Senior Secondary School, which currently has 280 enrolled students, with another school operating on the same premises in Jaipur’s Rath Khana area has sparked strong reactions from school officials.

A senior teacher at the school told ThePrint that the institution, established in 1949, would lose its identity if merged with another school. “This is the only school in all of Jaipur named after Pandit ji (Deen Dyal Upadhayay). Pandit ji was one of the founders of Jana Sangh. How can the BJP government, which claims his legacy, merge this school? The opposite should have happened,” the teacher said, requesting anonymity.

Story of zero- or low-enrolment schools

According to government officials, a large number of schools that have been merged had zero or low enrolment. To understand the reason behind the same, ThePrint visited some of these schools and found out that the locals stopped sending their children there due to dilapidated infrastructure.

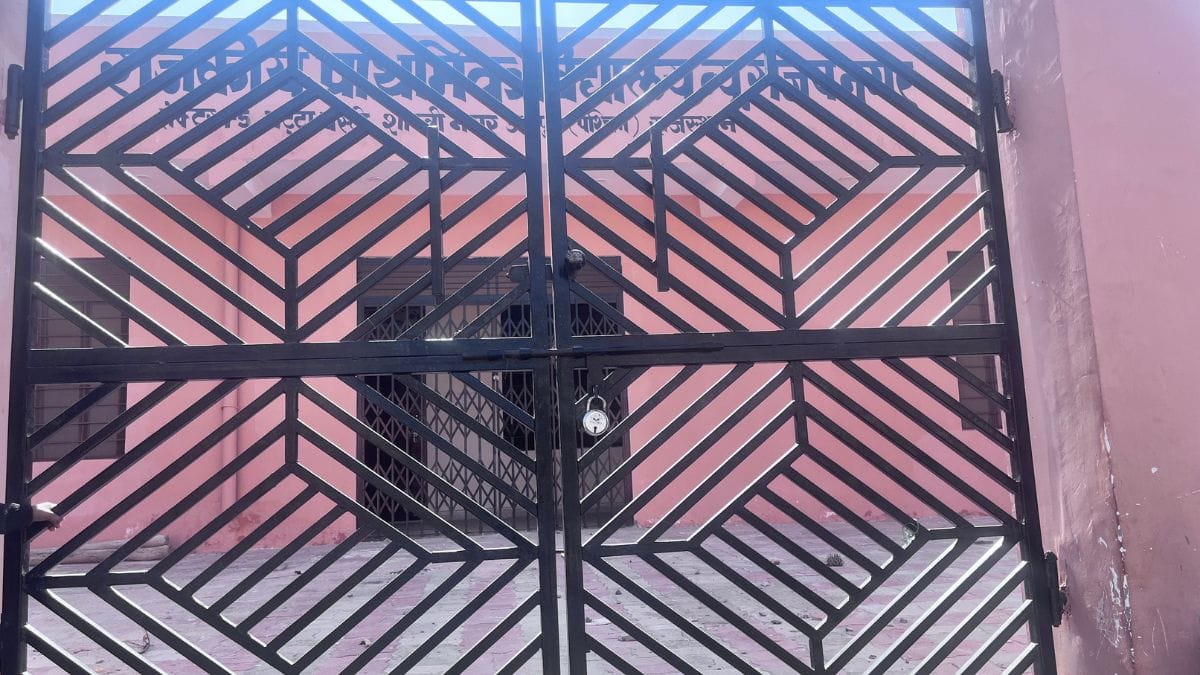

For instance, the government upper primary school in Narsingh Colony—situated on the outskirts of Jodhpur—was merged with a senior secondary school in Mandore due to a total lack of enrolment. The school’s dilapidated building is now locked and abandoned.

Locals told ThePrint that the school had more than 50 students until roughly two years ago. “During the monsoon of 2023, the building started leaking, and a section of the roof collapsed. Despite this, there were no repairs. As a result, parents began pulling their children out. There was no other primary school nearby, so parents were forced to send their kids to a small private school in the area. By last year, only four to five students remained. The school had to operate from a nearby house for a few months,” said Pokar Ram, a resident, to ThePrint.

Another government primary school in the Kadam Kandi area, which is 15km away from Jodhpur city, has been merged with a senior school in Chokha village. However, when ThePrint visited the school, the locals said it was operating from the premises of an ashram and only two to three students were enrolled.

“Parents were already sending their kids to Chokkha village because the Kadam Kandi school had no proper infrastructure. It is almost 3km away from here,” said Bablu, a resident.

Similarly, another school 40km from Jodhpur in Bodvi Kalan Baori has been merged with a senior school in the nearby Bodvi Khurd village.

According to the school principal, Govind Singh, the school had just one student since August last year. “There were two staff members, including me, and we had just one student. We tried to bring more enrolments, but it did not work out,” he told ThePrint.

Kumar, the teachers’ association president, pointed out that many schools saw no new admissions in Class 1 last year due to changes in the age criteria. Under the National Education Policy 2020, the entry age for Class 6 has now been raised to six years. “Many young children still attend anganwadis and were expected to transition into schools this year. How will they manage when the government has shut down their schools?” he asked.

He expressed concerns about the future of teaching positions. “The government claims it is not shutting down schools, just merging them. But when one school merges with another, its teachers will also be merged. No new teaching positions will be created. Where will all the B.Ed graduates go?” he questioned.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Govt announces centre for excellence in AI for education; 5 national centres for skilling