New Delhi: While hearing the stray dogs matter, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court last week came down heavily on the municipal corporations of Delhi NCR. “What is your stand? This is happening because of the inaction of the municipal corporation. The government does nothing. The local authorities do nothing,” Justice Vikram Nath, one of the judges on the bench, said during the hearing.

The Supreme Court later that day reserved its verdict on petitions challenging its 11 August directive that all stray dogs in Delhi NCR be rounded up within eight weeks and moved to shelters, never to be released back into public spaces.

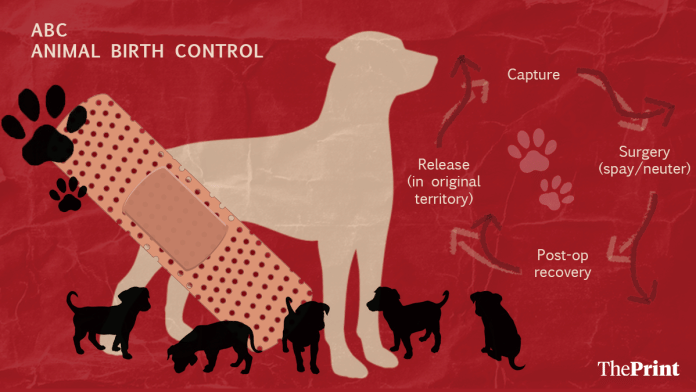

At the centre of the debate on stray dog management is the Animal Birth Control (ABC) or sterilisation programme. It is shaped by the Animal Birth Control Rules, established under The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960. The ABC Rules were first introduced in 2001 and updated in 2023.

The rules provide the legal framework for managing stray dog populations through sterilisation and vaccination against various diseases including rabies, and are internationally considered as the humane and scientific approach to controlling rabies and dog bites.

Animal welfare groups and veterinary experts the ThePrint spoke to said the ABC programme, if implemented properly, is the only sustainable approach to managing the stray dog population. The World Health Organization (WHO) too has consistently endorsed sterilisation and vaccination as a most cost-effective strategy.

Meet Ashar, lawyer and director of cruelty response at PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) India, described the Supreme Court’s directive as a “knee-jerk reaction”. He said it seemed as though the authorities were hoping for a magic wand that would simply make all of Delhi’s estimated 10 lakh stray dogs disappear—something, he stressed, “is not going to happen in the next 10 years either”.

Ashar warned that if the SC order was implemented, the focus of authorities would shift away from sterilisation under the ABC programme to merely catching and confining dogs. This, he argued, would worsen the problem rather than solve it.

“Even if you pick up 5,000 dogs, you are still leaving lakhs of other dogs on the streets to breed,” he told ThePrint, adding that prioritising confinement over sterilisation would only give the stray population more time to multiply.

Geeta Seshamani, co-founder of non-profit Wildlife SOS and vice-president of Friendicoes SECA, which rehomes rescued and abandoned pets, agreed with Ashar.

She stressed that the ABC Rules already provided scientific and humane solutions to deal with the issue, but the problem lies in poor enforcement. “The rules are more than adequate, but they have never been implemented strictly by the authorities,” she said.

Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) Deputy Director (Veterinary Services) S.K. Yadav acknowledged an ongoing funding issue, with payments to ABC centres pending for the past six months.

A senior official told ThePrint that the problem lies not only with the veterinary department, but with the entire MCD. Even employee salaries have been delayed, largely due to the previous government’s failure to release funds.

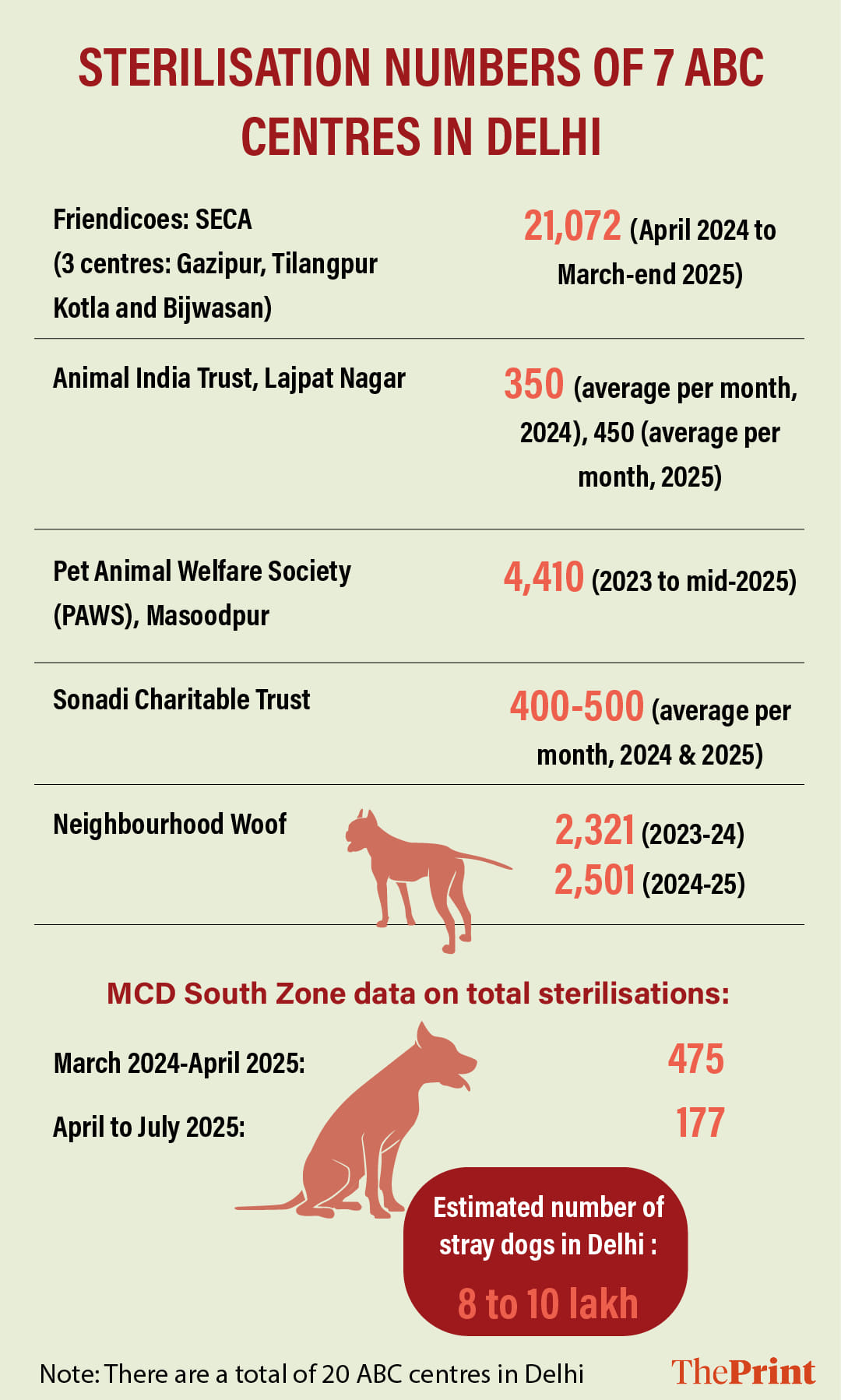

The estimated population of stray dogs in the capital is 8 to 10 lakh.

ThePrint reached several ABC centres for data on the number of sterilisations they had individually conducted.

Also Read: How Delhi is mobilising to save its street dogs — shelters, safe houses, and watch patrols

What ABC Rules say

To operate a sterilisation centre in India, one must follow a clear, legally mandated process laid out under the Animal Birth Control (ABC) Rules, 2023. These rules govern how the stray dog population is to be managed through vaccination and sterilisation.

The first step is obtaining recognition for the centre from the Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI). This is compulsory under Rule 5: no municipal body or registered animal welfare organisation can undertake sterilisation or vaccination of stray dogs without this approval.

Applications for the same are reviewed by a dedicated project recognition committee within the board.

After approval, the organisation is required to set up adequate infrastructure for the ABC centre. This includes operation theatres, post-operative recovery spaces, kennels for dogs before and after surgery, and a quarantine area for sick or aggressive animals.

Equally important is staffing the centre with qualified veterinarians, para-veterinary staff, dog catchers, and support workers. All personnel involved in the sterilisation and care process must undergo AWBI-approved training to ensure humane handling and medical competence, the ABC Rules state.

ABC centres are designed to work in partnership with local authorities such as municipal corporations or gram panchayats. These bodies identify areas with high stray dog populations, assist with dog capture, and monitor the birth control programme’s impact on the ground. For sterilisation, dogs are captured humanely, transported safely to the centre, examined for fitness, sterilised under sterile conditions, and vaccinated, particularly against rabies.

Post-surgery, dogs receive food, antibiotics, and rest until they are certified fit by veterinarians. Once fully recovered, each dog must be released back to the exact location it was picked up from, since displacing them can lead to territorial disputes and increase the risk of human-animal conflict.

The responsibility of the centre continues beyond sterilisation and release.

Detailed records of the animals must be maintained, covering identification, medical history, surgery details, release information, and even the count of reproductive organs removed daily. These reports are to be submitted regularly to both the AWBI and local authorities. Alongside this, the centres are expected to build community awareness about the ABC process and its role in managing the stray dog population.

Also Read: Mass culling to dog tax & abandonment fine, how various countries manage stray dog population

Challenges faced by ABC centres

While ABC centres have their own shortcomings in terms of working standards as ThePrint reported earlier, they are also grappling with challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and a lack of funding—resources that were meant to be provided by the MCD, according to the Rules.

Delhi currently has 20 ABC centres, which the MCD has relied on to house stray dogs picked up ahead of Independence Day, days after the SC directive.

“There are two very dangerous aspects of this order,” said Ayesha Christina Benn, who runs Neighbourhood Woof, an ABC centre in Delhi that is currently undergoing construction to create more space to hold dogs.

“The 20 sterilisation centres where the dogs are being rounded up have a capacity of barely 1,000—we know this from the round-ups ahead of the G20 (2023 summit in Delhi). If the dogs are not released, these centres will fill up quickly. Then where will the post-op dogs go? And with the mating season underway, the puppies that will soon be born won’t be sterilised either.”

Ayesha said she had been asking the Delhi government for improvements in infrastructure for the past seven years and even had the same on record. “I’ve been begging for it,” she told ThePrint, pointing out that all the ongoing construction at her centre was being carried out with public funding.

“Can you imagine the scale? Is it really the job of a small NGO to fix government infrastructure?” she asked in disbelief. She explained that they had been left with no choice—either they didn’t comply with the ABC rules or did such a poor job that the authorities would shut them down, or took it upon themselves to get the work done.

Her centre, she said, currently holds more than 70 stray dogs that were rounded up following the SC order and ahead of Independence Day celebrations.

Ayesha told ThePrint that over the past four years, a larger number of stray dogs have been brought in by animal lovers and caregivers to Neighbourhood Woof, compared to the MCD.

In 2020, she received 593 dogs from the MCD and 2,415 from caregivers. In 2021, the numbers were 897 from the MCD and 2,123 from caregivers. In 2022, 632 dogs came from the MCD while 2,271 were brought in by caregivers. In 2023, the figures stood at 600 from the MCD and 1,721 from caregivers. Most recently, in 2024, she received 433 dogs from the MCD and 2,068 from caregivers.

Five other ABC centres ThePrint contacted confirmed that they had been instructed not to release any dogs, pushing their facilities to full capacity and hampering ongoing sterilisation efforts.

Dr Vijay Kumar, who runs Sonadi Charitable Trust in Najafgarh—the largest ABC facility in Delhi—said the first and biggest hurdle is catching the dogs.

“Until you can catch a dog, how can you sterilise it?” he asked, stressing that in the past 20 years, there has been little effort by the government to train dog catchers or provide trained workers at ABC centres. Instead, he said, municipal workers continue to rely on outdated methods for the same with no formal training provided by the MCD.

The other major challenge, according to him, is funds. Currently, NGOs are paid Rs 1,000 per dog for sterilisation, but Kumar said the figure does not even begin to cover the actual costs. “From medicines to doctors’ fees, everything has gone up. At least Rs 1,500 per dog should be paid if we are expected to maintain proper standards,” he said, adding that payments to his centre from the MCD have been pending for six months.

He also highlighted that centres like his often house injured or abandoned dogs for free, with no compensation from the authorities, even though this requires food, medical care, and disposal costs in the case of rabid animals.

Dr Sanjay, who runs an ABC centre in Usmanpur, said: “We are now taking in all the dogs through our app, but if microchipping is also made mandatory, the costs will go up. We’ll need more staff, and the process itself will require additional funds.” Microchipping involves implanting a small, electronic device under the skin of an animal.

Seshamani echoed similar frustrations. She said the authorities had failed to provide even basic infrastructure support, refusing to expand the number of centres despite Delhi’s growing dog population. “The rate we are paid doesn’t cover food, medicines, or staff costs. Yet, stellar performance is expected from us,” she said.

She argued that if the government has funds to maintain lakhs of dogs in shelters, it should instead invest that money in expanding and strengthening the ABC programme. “If you plough those funds into ABC units, increasing the rate for surgeries and medicines, I am confident we can achieve a fully vaccinated, sterilised population,” she told ThePrint.

Both Kumar and Seshamani further underlined gaps in implementation of the ABC Rules, particularly when it comes to managing aggressive dogs or those prone to biting.

“That part of the Rules is often glossed over,” Seshamani noted, adding that failure to address this issue only fuels public resentment against the ABC centres which includes the dog feeders as well.

Despite the challenges, all of them agreed that the ABC programme remains the only solution to managing Delhi’s stray dog population. “If we improve the infrastructure and implement the rules properly,” Seshamani said, “we can create the safest, healthiest street dog population in the world.”

ThePrint spoke to one more ABC centre which wished to remain anonymous but echoed similar concerns.

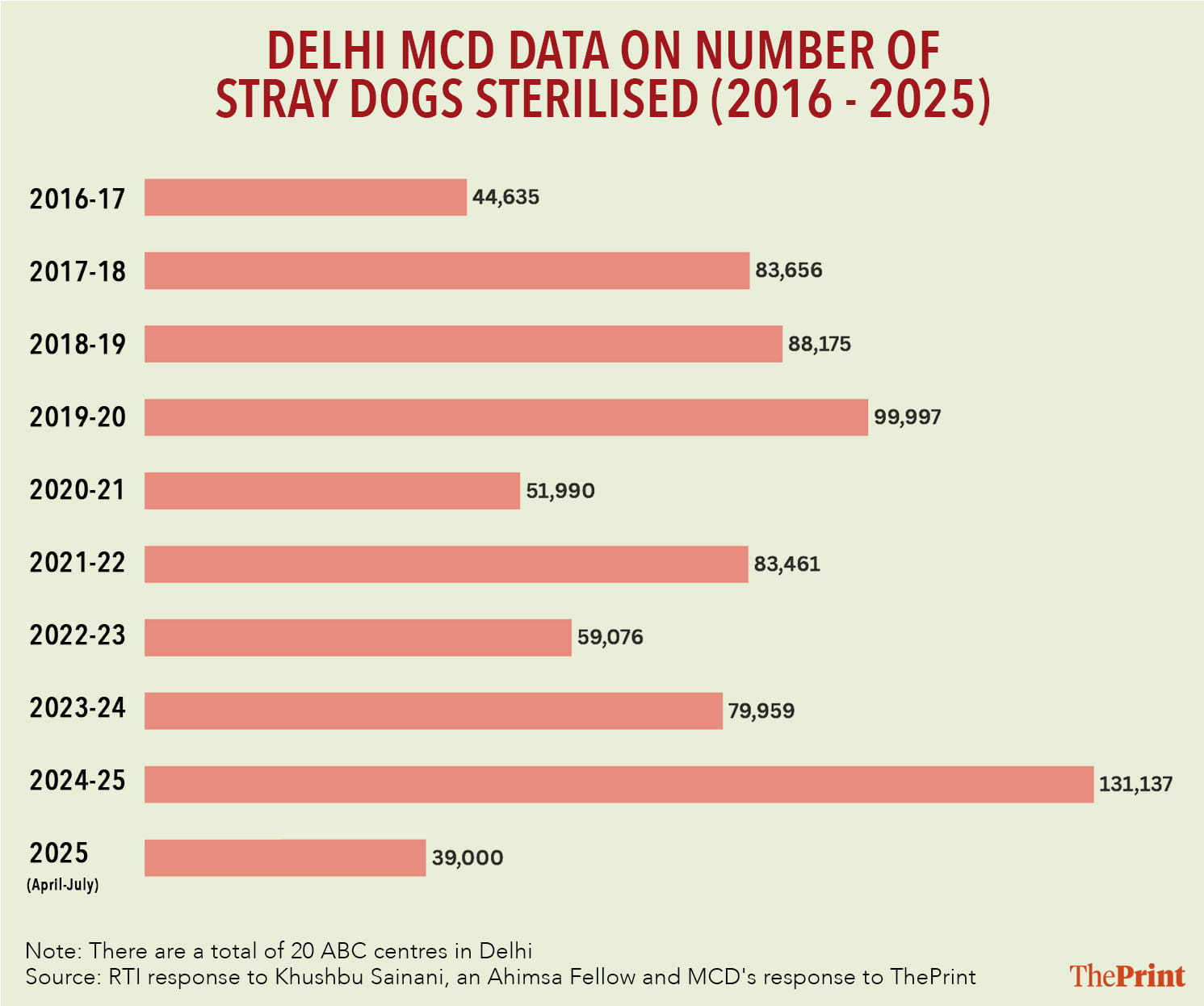

According to MCD estimates, more than 65,000 stray dogs were sterilised and vaccinated in Delhi between March and August this year.

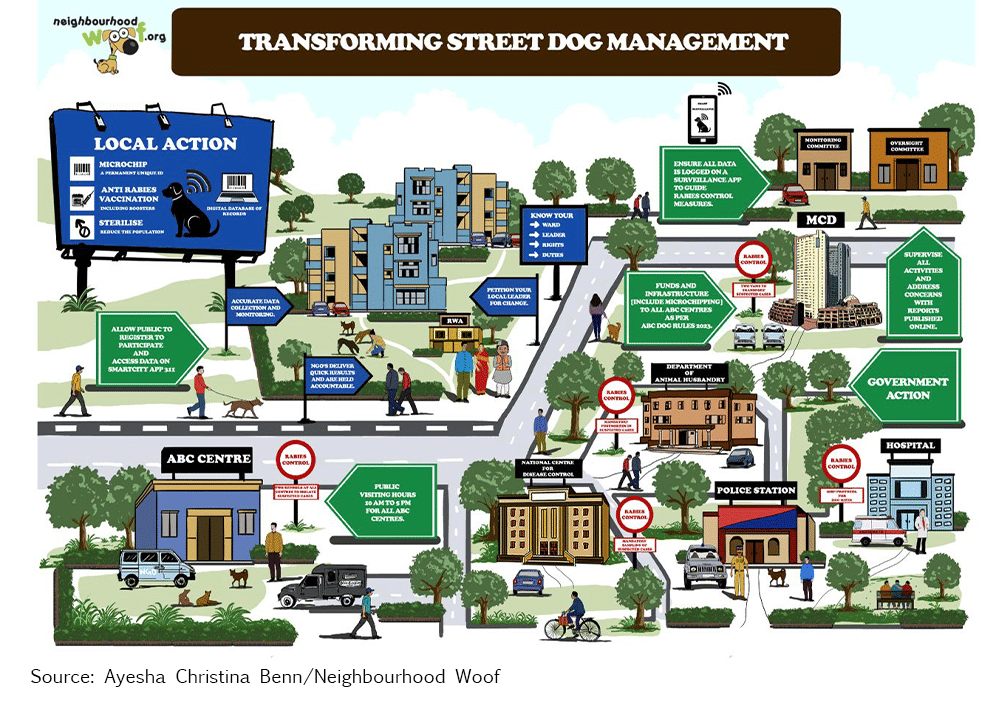

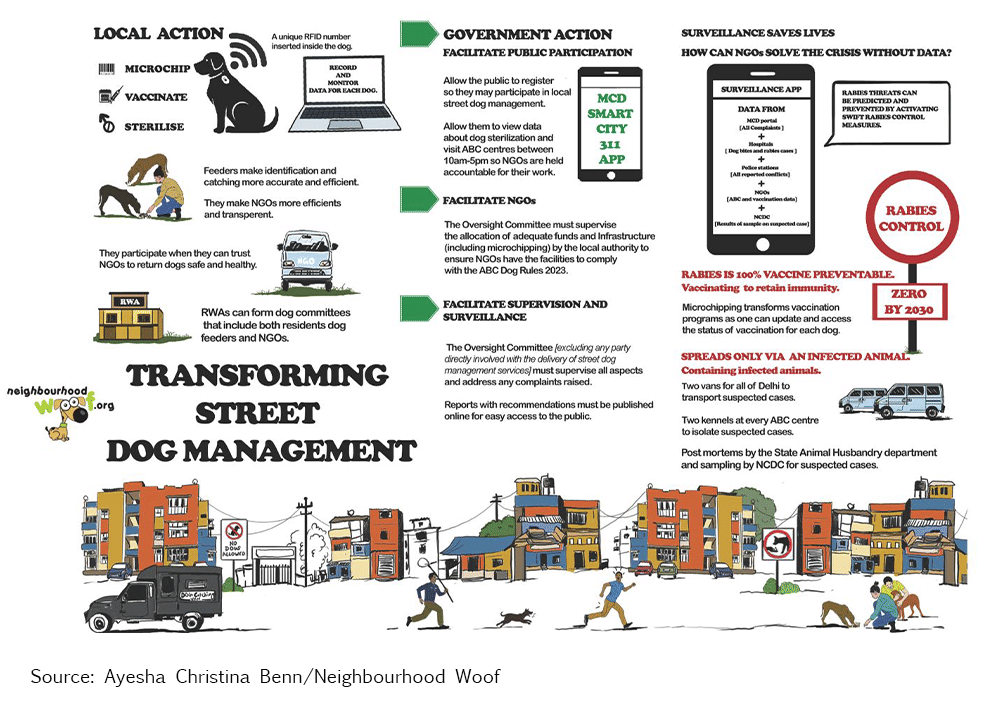

Proposed action plan

Neighbourhood Woof’s Ayesha has put forward a detailed action plan for effective implementation of the ABC programme and rabies control. She also presented the roadmap in a meeting with the MCD on 8 August, which was also attended by Delhi minister Kapil Mishra. “This is a grassroots-level roadmap to actually count, sterilise, vaccinate and microchip dogs. The idea is not just to look at one neighbourhood in isolation, but to expand the approach to adjoining localities as well, ensuring that no pockets of dogs are left behind,” she said.

She also emphasised the importance of coordination between caregivers across neighbourhoods and highlighted that NGOs must carefully map and plot data ward-wise.

Only then, she explained, can authorities identify areas that are often neglected—such as slums, parks, or marketplaces where dog populations exist but permanent residents do not.

The plan also outlines the role of government action. It calls for stronger surveillance, rabies control and mechanisms for transparency. Ayesha insisted that NGOs must be held accountable and that data uploaded by sterilisation centers to the Smartcity 311 civic app should be made publicly accessible.

“People should be able to see which dogs are picked up, sterilised, and dropped back each day. Citizens should also have the right to visit ABC centres,” she said.

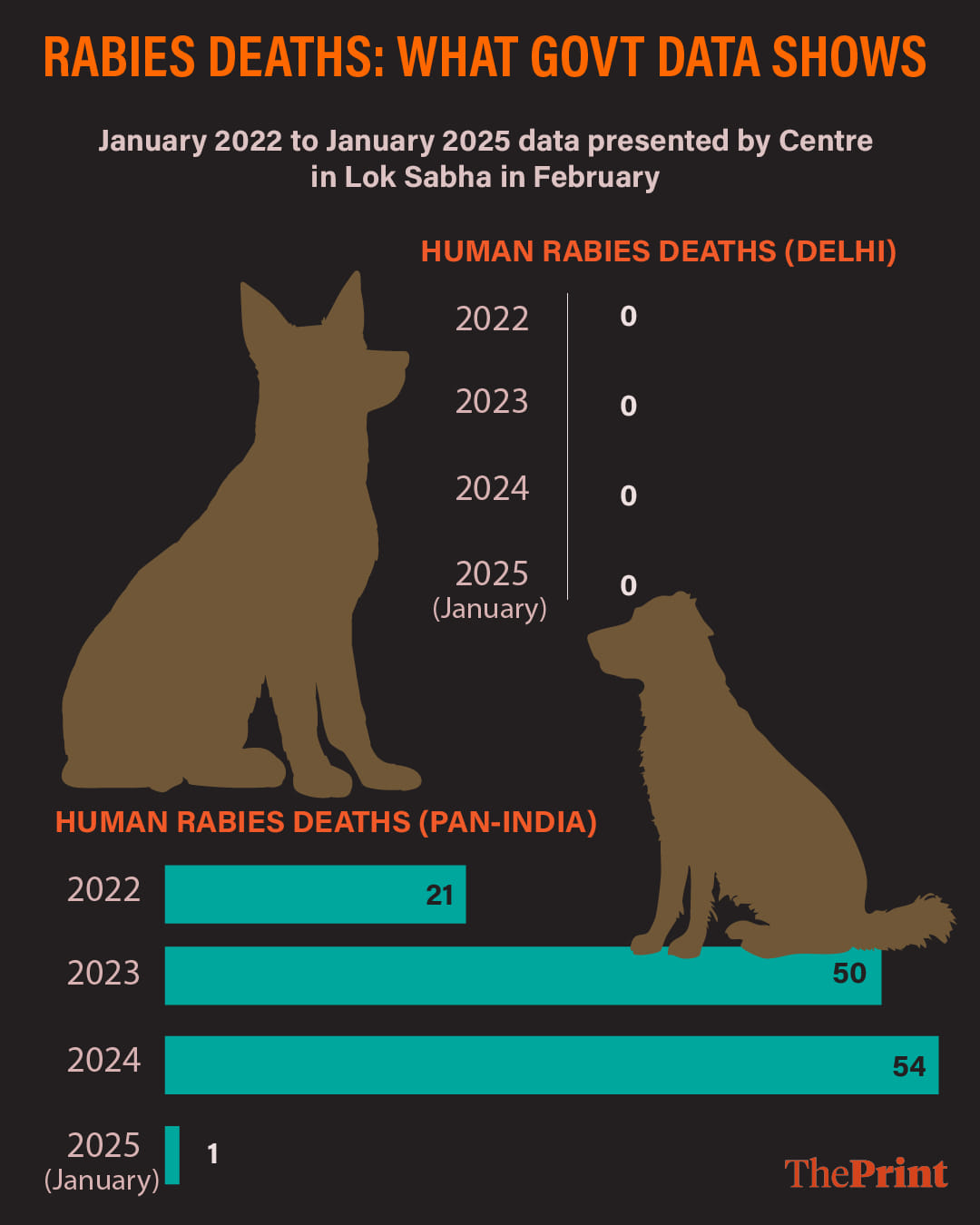

On rabies control, she pointed to data from the Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairy stating that there were zero human rabies deaths in Delhi from January 2022 to January 2025. “We are closer than ever to eliminating rabies from our dog population. Scientific methods exist, and we only need to activate them,” she said.

She simplified the isolation and containment protocol for rabid dogs into four actionable steps that already exist in policy and require minimal expenditure. She called for just two isolation vans for the entire city to pick up suspected rabid dogs within two to three hours, and two isolation kennels in shelters to house these dogs safely.

She stressed the need for rabies isolation wards in every ABC centre, which do not currently exist in most centres despite being mandated by protocol. She also emphasised that the animal husbandry department must undertake mandatory sampling of dogs suspected to have died of rabies, with samples sent to the National Centre for Disease Control for confirmation through the standard D-FAT post-mortem rabies test.

Alongside this, she recommended vaccination and containment drives in the affected areas, with all related data being shared with NGOs so that they can plan sterilisation and catching efforts accordingly. “It doesn’t take crores of rupees or huge infrastructure. Just two vans, two kennels, proper sampling, and transparency. With this, we can achieve a rabies-free status for our dogs—and ultimately, for Delhi,” she told ThePrint.

Ayesha has also challenged the 11 August order of the SC mandating removal of stray dogs from the streets to shelters.

This is an updated version of the report.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: As animal rescuers slam Delhi CM’s stray dog relocation directive, a look at issue from a legal lens

Dog lovers and dog feeders are absolute nuisances for human society. A well-knit community, their love for dogs, especially strays, far outweighs their love for fellow human beings. They can effortlessly feel the pain of a starving stray dog but are just unable to connect with the pain and fear of a young mother whose child was mauled to death by a pack of stray dogs. It is this lack of empathy and compassion for fellow human beings which makes this community an absolute nuisance.

It’s sad and disappointing that The Print has allowed it’s platform to be used and abused by these “activists” to champion the “cause” of stray dogs while deliberately and maliciously downplaying the human cost of this conflict. Quite conveniently, the blame was put on the government.

Nothing works in socialist India except corruption.