Bhopal: Every weekday morning, 21-year-old Nirmala Uike waits for her father to leave for work, not because she wants him gone but because she needs his room to take classes for neighbourhood children, for free.

Uike lives in Bhopal’s Gautam Nagar area, where nearly a thousand people, mostly daily wage workers or nagar nigam (municipal corporation) employees, inhabit slum dwellings. When schools shut down due to the pandemic, many of the slum’s children were left wandering around aimlessly. Nirmala, a 12th-standard passout who is married and has a child of her own, decided to do something about it.

“Many families just gave in to fate and let their children go astray when schools shut down. For people here, food and shelter are most important, and education was never a priority. But, it was difficult to accept it and (taking classes at home) seemed to be the most logical way out,” Uike said.

She is not the only one who felt this way. Neighbourhood initiatives to improve the learning outcomes of underprivileged children have cropped up not just in Gautam Nagar but other pockets of Bhopal as well.

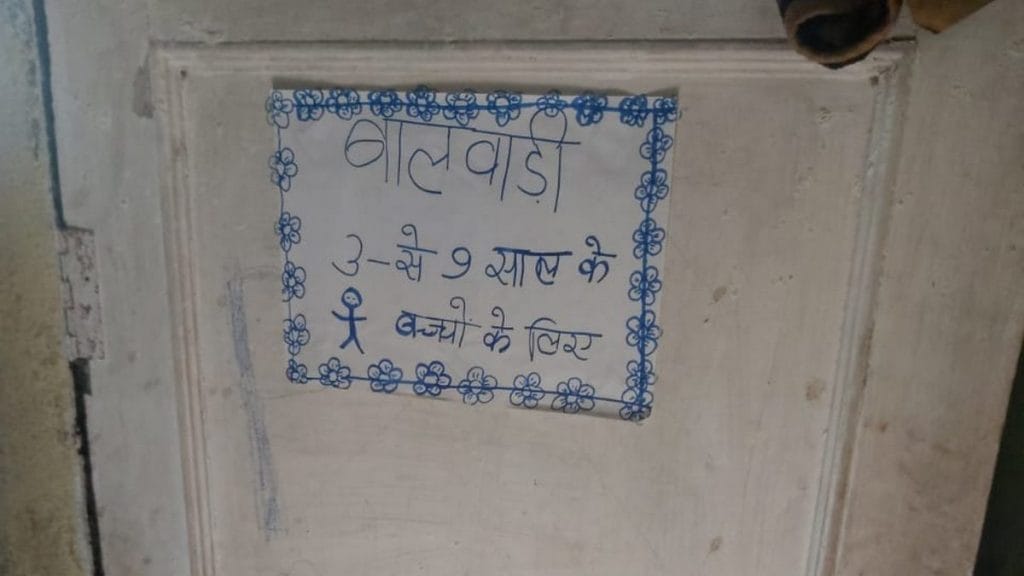

In Gautam Nagar alone, at least four women in the basti have taken it upon themselves to teach children aged between 3 and 14, without any type of payment. The women have been taking informal classes for about seven months, either from home or other makeshift spaces. Attendance is not mandatory and sometimes unwilling students have to be tempted into the “classrooms” with chocolates and biscuits, but the women do whatever is necessary to at least get the youngest children on board.

Sheetal Uike, 19, recently joined the initiative. She teaches children under a tree just outside a government building in the basti since there is no space in her house. “I have seen children who cannot recognise even simple shapes, sizes, numbers, and alphabets. Even though the education in government schools is not world-class, at least we could do this much at their age. We are trying to make up for the basic learning that small kids have missed out on,” she said.

The Economic Survey 2021-22 noted that it is difficult to entirely gauge the impact of repeated lockdowns on children’s education, but it pointed towards last year’s edition of the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) conducted by the NGO Pratham, which indicated that enrolment and learning have both suffered during the past two years.

The observations of women like Nirmala and Sheetal mirrored what the survey found: primary school-age children aged 6-14 years who are not enrolled in schools doubled from 2.5 per cent in 2018 to 4.6 per cent in 2021. The report also voiced concern about pre-primary and primary-age children’s learning outcomes since they “have already missed many months of engagement during the critical period of maximum brain development”.

The report further pointed out that without remedial measures, the “opportunity to help them build firm foundations during the vital early years will be lost”.

This Monday, the Madhya Pradesh government announced the reopening of schools with 50 per cent capacity across the state and that online classes would also continue. However, it will likely be an uphill climb to bridge the learning gaps caused by school closures.

Also Read: 1 year of lost learning will take years to recoup, says India study urging reopening of schools

A small boost for homegrown teaching initiatives

In Shyamnagar, Bhopal, more than 1,500 people live in slums. Before the pandemic, most children here went to a two-room government school nearby. After school closures, many abandoned any type of education at all, either because they did not have resources for online learning or because they simply got no value from such classes.

Due to concerns about toddlers playing unsupervised in unsafe conditions, Mamta Yadav, who is in her 30s and lives close to the slum area, started an informal mini-school. “It was difficult to see toddlers roaming around men who drank in the locality during the day,” she said, adding that she too tried to bring in kids by offering them sweets.

“The kids needed some incentive to attend. We didn’t just hold classes but also played games so that they don’t freely roam and do nothing. We had to explain what Covid-19 was and how they should keep their masks on at all times. It was disheartening to see things happening the way they were, at least around me. I had to do this,” Yadav said.

Similarly, 19-year-old Kausar Ali, who is currently pursuing a paramedical course at the Rajiv Gandhi Medical College, started classes for toddlers in July last year in Rishinagar, a congested locality about 15 minutes from Shyamnagar.

“I taught my (4-year-old) niece during the lockdown. Her friends, who are around the same age, also got interested, so I started taking these classes on a bigger scale outside my room. I knew that they could understand nothing from online classes,” Ali said.

Fortunately, the work of women like Mamta Yadav, Nirmala Uike, and Kausar Ali is getting some recognition and support.

Shivraj Kushwaha from Sahara Saksharta, an NGO working on child rights in Bhopal, said his organisation is trying to assist these informal teachers, even if modestly, via the non-profit Child Rights and You (CRY).

“They could at least get Rs 1,000-5,000 if this is brought under CRY, and it would be more sustainable if we could introduce some structure,” Kushwaha said.

According to him, these women are providing a valuable service. “Teachers like Mamta have been trying to bridge this gap caused by lockdowns. I am not too optimistic about online classes for reasons known — the digital divide has pushed children from the government schools far behind,” he said, adding that the government should explore a more flexible syllabus and foundational learning courses once schools resume operations.

Addressing the digital divide

In Bhopal, children from poor economic backgrounds attending government schools are at the forefront of the offline-online debate.

Parents of older children have often made a valiant effort to facilitate online classes, but the costs have been heavy and the learning gains unclear.

Suganti Gond, a 38-year-old resident of Shyamnagar, has four children. She took out a loan to buy a smartphone so that her children could attend at least one hour of classes every day.

“There are WhatsApp groups created by teachers. They keep sending videos which explain concepts and there are worksheets distributed every two or three weeks. I did all I could for (my kids) to access these classes. I even mortgaged my jewellery,” Gond said.

However, even children who do have smartphone access frequently struggle with online learning, and many are compelled to take tuitions.

According to Mahendra Yadav, ASER’S Madhya Pradesh programme coordinator, the percentage of children taking tuition classes in the state has increased to nearly 28 per cent in 2021, from about 15 per cent in 2018.

He added that about 30 per cent of families in MP did not own smartphones, leading to even greater learning loss. “Although 90 per cent of families across the state received textbooks and school materials, the online education gap continued to widen during the pandemic,” Yadav said.

Like Shivraj Kushwaha, Yadav believes the government will have to adopt remedial measures when schools reopen. “We have given some suggestions to the state government — there should be foundational or bridge courses for all sections. We also mentioned in our document that even if schools reopen, the syllabus should be flexible since students will not be at the same level. Previous structures, unfortunately, won’t work,” Yadav said.

Speaking to the Print, A.K. Vijayvargiya, additional district programme coordinator of the District Education Office, said there are currently bridge classes for Class 9 onwards. “The current structure allows us to ensure that students who fell behind have support to pass in all subjects. This is happening at the district levels,” he said.

When asked about remedial and bridge courses for primary sections, Rakesh Dewan, academic programme coordinator of the Zilla Education Centre, said that currently there is a programme to identify students [who need additional academic assistance] in 8th grade. “Once we have a blueprint for primary sections, we will follow that and implement it,” he added.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: School lockdowns in India have robbed a generation of upward mobility