Shravasti/Bahraich/Balrampur: Danish Mansoori, 20, thinks he is one of the “lucky ones”. In 2020, he left his hometown Bhinga in Uttar Pradesh’s Shravasti district for a bachelor’s degree in ayurveda, medicine, and surgery (BAMS) from a paramedical college. However, his destination was not Mumbai, Delhi, or even Varanasi, but Bihar’s Siwan district, which is better known for lawlessness than higher education opportunities.

“My 12th class marks were not good,” he explains when asked why he picked Siwan, adding that anything seemed better than staying on in Shravasti. “There are just a handful of government and private colleges, where teaching is not good. Also, there are no jobs. After graduating, I would have remained unemployed.”

In the midst of Uttar Pradesh’s seven-phase election, which started on 10 February, promises and promotion fill the air. While the opposition parties speak of change, the incumbent BJP government helmed by Yogi Adityanath brandishes its achievements in development.

Yet, even the best publicity campaigns cannot mask the ground realities in some districts.

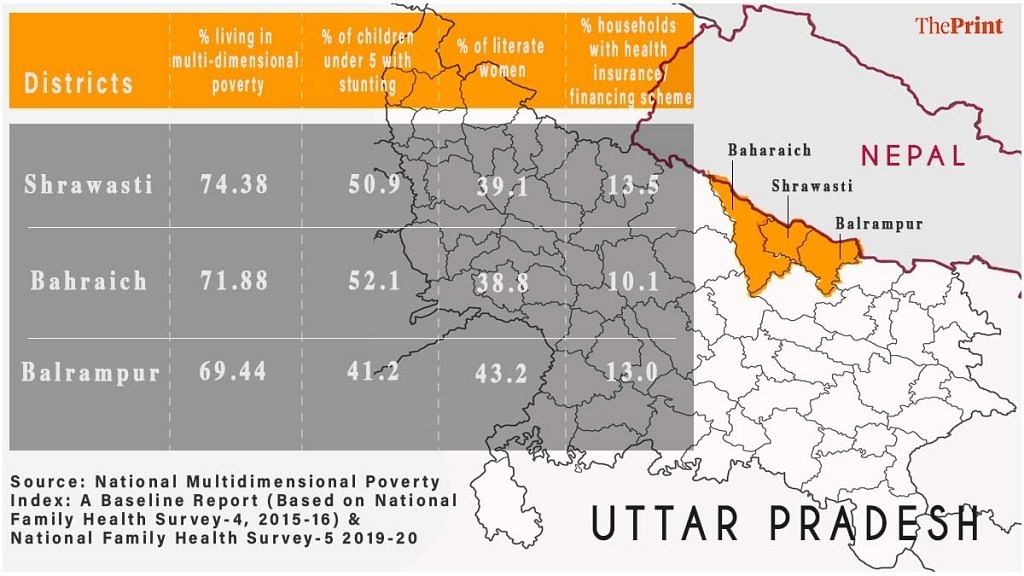

Last November, a few months before the poll dates were announced, the government of India think-tank NITI Aayog published a report on the national Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index (MDI). This report scored hundreds of districts across states on their MPI, which is a metric of “deprivations” faced by households across the dimensions of health, education, and living standards.

Out of the four worst performing districts across the country on these parameters, three are in Uttar Pradesh.

Shravasti ‘tops’ the list, with 74.38 per cent of the population deemed to be “multidimensionally poor”, followed by neighbouring Bahraich (71.88 per cent) in second position, and Balrampur (69.45 per cent) in fourth. The third and fifth positions go to Alirajpur (71.31 per cent) and Jhabua (68.86 per cent) districts in Madhya Pradesh respectively. Among the top 100 worst performers, UP districts occupy 15 positions in all, according to the NITI Aayog report.

It is worth noting, however, that the report is based on 2015-16 data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-4, and the districts have improved on certain parameters of maternal and child health, literacy, electricity coverage, and so on since then. Shravasti, Bahraich, and Balrampur are also part of the Centre’s Aspirational Districts Programme, which was launched in 2018 to effectively transform the 117 most under-developed districts across India.

However, improvements notwithstanding, these districts are still lagging behind on many fronts. There are high illiteracy rates, malnutrition among children, substandard education facilities, absence of decent employment opportunities, decrepit infrastructure, and poor sanitation.

ThePrint travelled extensively across the three poorest districts in UP to observe what extreme “multi-dimensional poverty” looks like on the ground.

Also Read: Unemployment and unlimited data pack — UP’s youth are neither angry nor idle

Malls & showrooms, but few private schools or coaching centres

A smattering of monasteries, temples, and shiny hotels create an initial impression of prosperity as one drives along the national highway connecting Shravasti — an important stop on the Buddhist and Jain pilgrimage circuit — with Bahraich on one side and Balrampur on the other.

The main road leading to Bhinga, the district headquarters of Shravasti, also has all the trappings of an up and coming small town: Bike showrooms, mobile shops, a Reliance Trends mall, and an India Fashion Bazaar with posters announcing a 30 per cent discount on woollen wear. Slow down and go a little deeper, though, and the façade drops away.

It’s a sunny Sunday morning in February, and the aforementioned Danish Mansoori is relaxing with friends on a bench outside a hardware shop in the main market of Bhinga. Mansoori makes it clear he is only a temporary visitor and will return soon to Siwan, where he is a second-year student at the Mahatma Gandhi Paramedical College.

According to him, Bhinga is just a “kasba” (mofussil town) with nothing to offer. “There is hardly any development here, just see the condition of the roads,” he says. Indeed, many of the roads in and around Bhinga are not just potholed and half-filled with slush, but also lined with mounds of garbage.

Mansoor counts the blessings that have allowed him to pursue opportunities elsewhere while his friends still stagnate in Shravasti. “My father is a local contractor and I also have relatives in Patna. Most of my school friends are here [in Bhinga] only, some are studying in the degree college, many have taken up small work here and there to help their families,” he says.

Even small jobs are not easy to come by. There are no industries or factories in the district except for a handful of small sugar mills and brick kilns (the only large company in the region is the famous Balrampur Sugar Mills in Balrampur district). Government jobs are few and far between, and though there are a couple of Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), those who qualify usually need to migrate out to put their skills to use. In rural pockets, where agriculture is the mainstay, you can still find work in someone else’s field if you don’t have your own land to cultivate but these jobs pay a pittance.

Unlike many other small towns across India, Bhinga is quite bereft of the coaching centres and English-medium private schools with fancy names. The most impressive educational institution in the region, incidentally, is the swanky Maharaja Suhel Deo Autonomous State Medical College, which was set up in Bahraich in 2019, and is funded jointly by the Centre and state government.

“Markets (coaching centres, private schools) are not interested in coming here and setting up shop. People have poor purchasing power here, so markets have not responded,” Prashant Kumar Trivedi, a professor in the sociological studies department of Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow, says.

Urban pockets like Bhinga, though, are better off than the rural belt, which according to the 2011 Census, is where more than 95 per cent of Shravasti’s population of 11 lakh lives and, for the most part, farms for a living.

Hanging on by a makeshift wooden bridge

The Rapti River gurgles through Ikauna block, a little over 20 kilometres from Bhinga. It’s scenic enough if you are just passing by, but the river inundates fields and houses in low-lying areas for a good two or three months during the monsoons and cuts off connectivity.

In fact, villages like Rajgarh Gulahriya,Narayanjot, Mankoa Kondri, and Maulana Ghasiyari would have remained cut off from the nearest main market round the year had the villagers not pooled in their resources and built a temporary bridge at Kakra Ghat.

Getting to Kakra Ghat by road is painful too since halfway through the concrete gives way to a kutcha (mud) path riddled with slush-filled potholes. The bridge here, built with wood and thatched grass, is far from ideal. It is suitable only for pedestrians, cycles, and bikes, and is dismantled in the monsoon season so that the surging Rapti doesn’t wash it away. During the rains, villagers have to cross the river on ramshackle wooden boats, but nevertheless the bridge is still essential.

“It’s like our lifeline. Without the bridge, we have to take a long detour to reach the nearest market or hospital,” 27-year-old Narsingh Narayan Verma, a farmer from Rajgarh Gulariya, says. “The villagers have demanded a permanent bridge many times but there was no response,” he adds, before making his way across the bridge with his wife riding pillion.

Officials at the district magistrate’s office told ThePrint that a permanent bridge can’t be built at Kakra Ghat as the area is prone to floods and because the river changes its course often during the monsoons.

The lack of a bridge and proper road, however, is not the biggest problem here, according to Sunil Shukla, 40, who lives in Maulana Ghasiyari village.

“Yahan koi saadhan nahin hai (There are no amenities here). There are hardly any opportunities. It’s always been like this,” Shukla says.

Over the years, many small and marginal farmers have migrated to cities for better prospects, while those who’ve stayed want the next generation to leave.

“People like me who cannot leave because of family responsibilities live here, but I will send my children away once they complete their schooling,” Shukla says.

Shravasti lags behind on almost all social and development indicators, although there have been some improvements between the NFHS-4 and NFHS-5.

The average literacy rate in the district is 46.74 per cent, and according to the 2019-21 National Family Health Survey (NFHS), about 52 per cent women in the 20-24 age bracket got married before the age of 18.

Lack of awareness about contraception, especially among women, has also led to large families on average. The total fertility rate (TFR) has improved since the 2011 Census when it was 5.5, but at 4.2 according to NFHS-4 data, it is still much above UP’s 2.7 and among the highest in the country.

The combination of low incomes and large families has also contributed to the pervasive problem of malnutrition among children. About 51 per cent of children under the age of five suffer from stunting and more than 40 per cent are underweight; over 20 per cent qualify as “wasted” in terms of weight according to the NFHS-5.

However, according to anganwadi (rural childcare centre) workers who are tasked with spreading awareness about family planning, most people see children not as extra mouths to feed but as potential working hands.

Rimpi Rani, an anganwadi worker at Shravasti’s Sirsiya block, where the Tharu tribe lives, believes things are changing, but very slowly.

“We can only tell them, but what do we do if they do not listen? Here, they think that more children will only help add to the family income,” she says.

Ishan Pratap Singh, chief development officer of Shravasti, says the backwardness of this district is, to an extent, historical. According to him, even during colonial rule, Shravasti comprised a few scattered hamlets that were not well connected to the rest of the country.

“That led to a historical baggage on the district, where it wasn’t able to develop properly. After 1998, when it became a separate district, the problem of connectivity and transport persisted. That is one of the reasons why occupation has not diversified and a lot of people continue to depend on agriculture,” Singh, a 2017 batch IAS officer, says.

According to him, there have been improvements on indicators like health and education ever since the district came under the Aspirational District Programme.

“In terms of health, we have done a lot better, especially in terms of maternal care and reproductive health. The latest NFHS survey shows that Shravasti has more than 80 per cent institutional deliveries, the majority of which occurred in government facilities. Another area where we have improved is in terms of family planning and reducing the TFR,” Singh says.

Low literacy rate, little income, free rations

The literacy rates in Shravasti as well as adjoining Bahraich and Balrampur have always been well below the national average, and many children quit their schooling young. What is even more startling is how much this has been normalised. ThePrint encountered several youth between the ages of 18 and 24 who said they dropped out of school, but did not feel they missed out on much.

A standard line, with variations is: “I know how to write my name, I know how to do a bit of math. Kaam chal jaata hai (That’s enough to get by).”

Because of poverty and the fact that there are no opportunities locally, many families feel sending their children to school is a waste of time.

Haseemum Jahan, 40, a resident of Dularpur village in Bahraich’s Chittaura block, lives with her family of five in a one-room semi-pucca house. She says both her elder sons, 25-year-old Anees Ahmed and 22-year-old Tufail — dropped out after class five because she could not afford to send them to school. Her youngest, 16-year-old Riyaz, discontinued his studies too for some years, but is now studying in class five. The chances that he will finish school, though, look slim.

“There are no jobs here. My son will eventually migrate to a big city to earn his living and support the family like others his age. He will not get any job here even if he finishes school. Why should I then insist that he should complete his studies?” Jahan asks.

However, the family’s elder sons are currently not contributing much to the household income either. Anees went to Mumbai to look for work but returned home after the 2020 lockdown, and now does daily wage jobs that do not fetch more than Rs 300 a day. Tufail is learning to become a car mechanic but is not earning yet.

According to Anees, both brothers had tried to get work under MGNREGA, but were turned away by the village pradhan (headman) who said nothing was available.

Between Covid and lack of opportunities, the family tries to make do with free rations obtained under the Public Distribution System (PDS).

“My husband does not work because of ill-health. I am a daily wager and earn anything between Rs 200-250 a day, depending on the work I get. How do I feed a family of five?” Jahan says. As for her modest dreams, they are indefinitely on hold.

A toilet that the family started to build has been left unfinished and her plans to get her elder sons married is postponed because there is no space to house a bride.

Stories like Jahan’s are not uncommon. They abound in villages across the three districts.

“It’s a vicious cycle,” says Prof. Bibhuti Malik, dean of the social science department at Lucknow’s Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University.

“PDS is one of the few poverty alleviation programmes that has been very successful but it is not enough. It has helped in preventing hunger but development has to be understood in a broader perspective, encompassing other social indicators, be it health, education or infrastructure.”

Malik says the districts have tribal pockets and are in the Terai border area. “Demographically, they are at a disadvantageous position to start with. What has further compounded the problem is that the government’s efforts in developing these areas have lagged behind for a long time.”

Another reason for these districts remaining backward for so long, Malik says, is because there is no demand for public accountability for poor delivery of services. “Nobody protests or demands services that are not there, there is no mass movement against poor development. People have got used to the system and take it as their fate. They are not able to see how they can come out of it.”

The three districts are like ‘D-class towns’

Low literacy means that many youth are relegated to living on poorly paid menial jobs if they stay on in their villages. When combined with large families, daily wages of Rs 200-250 don’t go very far.

People have low purchasing power in these districts, says Subhash Singh, the sole distributor of Amul and Dabur in Bahraich. “We treat Bahraich and adjoining districts as D-class towns. Because people’s spending power is less, we bring only low-priced FMCG items here. For instance, if a Rs 100 ice cream will be stocked by a distributor in Lucknow, here we will mostly stock ice cream priced between Rs 10 to Rs 20,” he says.

The low spending power is also reflected in the car loans given by banks. The average ticket size of car loan disbursed by State Bank of India’s main branch at Bahraich’s Padma Market in the current fiscal was just Rs 5 lakh. “Small size cars sell the most here,” says Mohammad Huzaifa, deputy manager at the branch.

Dr Prashant Kumar Trivedi, associate professor of sociological studies, Giri Institute of Development Studies, Lucknow, says that because of poor purchasing power, the private sector has avoided investing in these regions.

“The political class did not allow the region to develop either from the side of the state or the market. The spread of education is very limited. There is stark inequality, which has been widened because of the faulty policies of the government,” he says.

All three districts rely on agriculture, but since the poor have very small land holdings, they cannot sustain themselves. As a result, many families are forced to migrate out to get jobs.

According to Trivedi, Shravasti, Bahraich and Balrampur have been “dominated by landlords” for a long time.

“Land reforms were never implemented in these places. The political economy is dominated by the upper caste Brahmins and Thakurs, who have the social capital. Land inequality is very huge. Compared to the rest of the state, the upper castes have very large land holdings and many of the poor are landless,” he says.

Toilets to store wood, gas cylinders empty

In a scenario where new enterprises rarely develop, locals of the three districts vest most of their hopes on government schemes.While many people are beneficiaries of one or the other scheme— from MGNREGA to Swachh Bharat to Ujjwala — the overall implementation of these programmes varies across districts.

In many villages, toilets built under Swachh Bharat are now being used to store wood or food for livestock. In some places, community toilets have remained locked for a year, and where they are open, nobody goes because there is no water connection.

This is why many villagers like Rupa Devi of Paharpur village in Balrampur’s Gaisari block still defecate in the open.

She says the system is rife with corruption at the pradhan-level and caste and community affiliations often come into play while giving jobs under MGNREGA or expediting work under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, a housing scheme for the poor.

“Commission system chalta hain yahan (bribes work here). I paid Rs 5,000 to the pradhan to get my application for PM-Awas processed,” says Hazoora Begum, who got a house (without a toilet) a few months back in Bahraich’s Dularpur village.

Most villagers have got gas cylinders under the Ujjwala scheme but many have reverted to burning wood for cooking because it’s cheaper. Filling an empty cylinder costs around Rs 900.

Dr N.R. Bhanumurthy, vice chancellor, Dr BR Ambedkar School of Economics University, says schemes are incomplete without long-term behavioural change to “ensure that the money that has gone to an account is being used for the intended purpose”.

He believes that instead of making people dependent on freebies, the government should create opportunities that encourage self-reliance and also strengthen human development indicators like health and education. “There has to be a holistic approach,” he says.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Who will this village in UP vote for in 2022 election? The one Duijji Amma picks