Guwahati: A month after the final National Register of Citizens list has been published in Assam, the BJP’s demand that this be nixed and a fresh one be conducted seems to have found traction among Bengali Hindu women who find themselves excluded from the list.

A number of Bengali Hindus are among the over 19 lakh people not on the final NRC list that was released on 31 August. Those excluded are now awaiting their speaking order (that states the reason why they were excluded from the final NRC) and their rejection notice, following which they have 120 days to appeal their exclusion.

For the excluded Bengali Hindus, solace has come from the BJP’s stand that it won’t accept the NRC and that it will push through the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) in the winter session of Parliament. The CAB promises Indian citizenship to all religious minorities barring Muslims.

Also read: NRC must for national security, will be implemented in Bengal, says Amit Shah

Sarma’s statements bring relief

At Guwahati’s Lal Ganesh area, Bengali Hindus have found comfort in the statements of Assam Finance Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, who, on 23 September, made it clear that the BJP will reject the NRC and pass the CAB in Parliament.

“Under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Amit Shah there will be another NRC. Those laughing now will cry for sure,” he had said. “A law will also be passed to grant citizenship to those who came to India due to religious persecution.”

The statements found resonance with Pushpa Malik, who is the only person in her family to make it to the final NRC. Her two daughters and husband have been excluded.

Malik is now in favour of the introduction of CAB in Assam. “I want a new NRC, but I want CAB more. I don’t know the exact specifics of the Bill but I know that it is good for everyone and will help the people of Assam,” she told ThePrint. “Who knows what will come out of a new NRC?”

While many other women of Lal Ganesh’s Vivekananda Path want a new NRC, they also believe that the exercise is necessary for Assam.

“An NRC exercise is definitely required in Assam to ensure that no outsiders live in the state but with different procedures. Let us see the criteria and then we will decide,” said Alo Dhalli, who herself hasn’t made it to the list.

Dhalli submitted her father-in-law and mother-in-law’s passports along with her father’s migration certificate but did not not make the cut.

Had necessary documents but did not make it to the final NRC

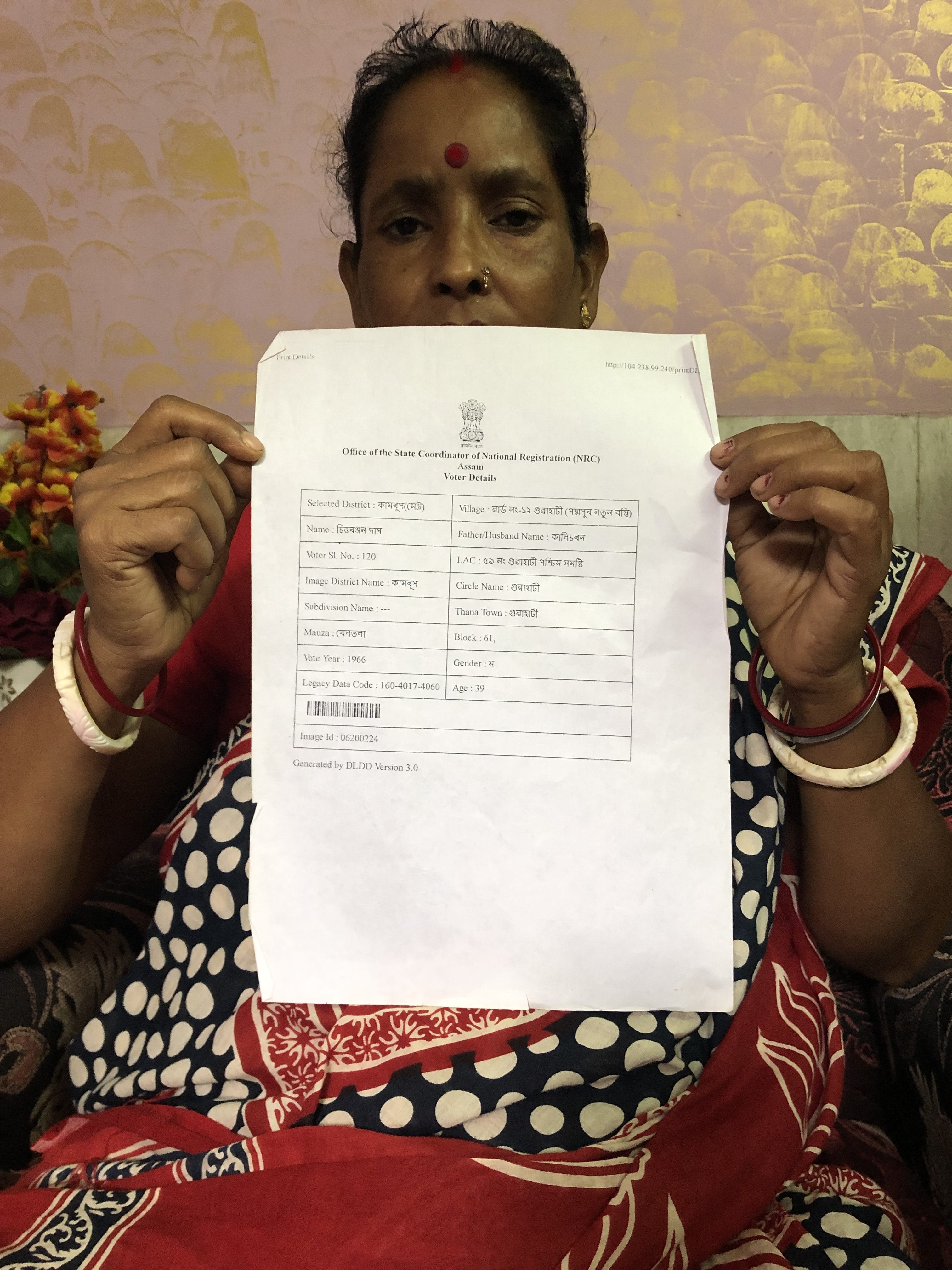

A number of the Bengali Hindus in Lal Ganesh not on the final list said they had submitted the necessary documents but were still excluded.

Sameli Das, 44, has lived in Lal Ganesh for the past 27 years. She is the only member of her family who has been excluded from the final NRC; her husband and all three of her children are on the final list.

Das said she submitted her grandfather’s refugee registration certificate (he came from Bangladesh in 1960) along with her voter ID and PAN card. Her grandfather was a freedom fighter, she said, adding that her grandmother who lives in Shillong still receives his freedom fighter’s pension. Das has no other documents to challenge her exclusion but she is not worried.

“I have nothing to be scared about,” she said. “I have all the required documents and I am a citizen of India.”

Her grouse is the financial and emotional toll it is taking on her family. Das said she paid Rs 10,000 to get all her documents in order and now pays her lawyer Rs 1,000 for each visit to the foreigners’ tribunal.

She has already seen him twice and will now meet him next on 10 October. “The expenses are so much that this time I have bought no new clothes for either myself or my children for Pujo,” said Das. “All the money is going into this.”

Like Das, Parvati Pal, 28, is not on the final NRC list along with her mother-in-law. But unlike Das, Pal is anxious and has been constantly worried. Pal said she submitted her father’s migration certificate from 1964 along with land documents. Her brother, sister and mother who live in Sapatgram in Dhubri district, submitted the same documents but have been included in the final register. Pal said she has no other documents to show apart from the ones already submitted.

The exercise has taken a toll on her 62-year-old mother-in-law’s health. “My son holds her tight because he is scared that his grandmother will be taken away from him,” said Pal.

She, however, is among the few in the locality who believe that the NRC should go completely. “There is no need for any NRC, either this one or a new one,” she said. “It should go completely.”

Also read: 5 law schools come together to help those excluded file NRC appeals in Assam

No more documents left to show

Almost all the women in the Lal Ganesh neighbourhood not on the final list have no additional documents to show aside from the ones submitted such as migration certificates, legacy data and land records.

Malik, who is in favour of the CAB, submitted her father’s citizenship documents from 1951 and the legacy data. She is worried if her daughters will get a job after being excluded from the list.

“None of us made it to the first list, but after that I submitted the legacy data for my children as well and my husband submitted his father’s citizenship documents,” she said. “Now I am the only one who has made it to the list and I have no other documents to submit for my two daughters. I don’t know what to do or how to protect them.”

Mitu Rai’s troubles go deeper than the other women in her locality — no member in the 45-year-old’s family is on the final NRC list.

“The verification officer told me not to worry as all my documents are fine but now I am not on the final list and neither are my husband and children,” she said. “I have no other documentation to show. My brothers and sisters showed the same documents and are on the list, how is this possible?”

She also has no lawyer to appeal her exclusion.

“Obviously I feel scared but what can I do? I was born in Lal Ganesh and have lived here my entire life,” she said. “I want a new NRC with correct procedures so that people living here are not excluded and troubled.”

Molina Das, 48, is, however, an exception. Molina, who has been living here for the past 30 years, had submitted her father’s legacy data but is now relying on her school certificate to challenge her rejection. “This is my only other hope,” she said. “If this also does not work, I don’t know what I will do. I am the only person in my family who has not made it to the list. I cannot go to the detention centre.”

Also read: New book captures Assam’s struggles with immigrants since landmark 1985 accord