Melghat (Maharashtra): In September this year, Anjali Kasdekar from Chikhaldara taluka’s Kulangana village lost one of her twins within 14 days of his birth. He was born underweight, just 1.4 kg.

In nearby Jamli Aar, Kiran Kasdekar lost her three-month-old daughter, Kaveri, in April this year due to sepsis with severe dehydration.

Deeper in the hills in Chikhaldara, in the Girguti village, Pramila Belsare’s four-year-old son, Aatish, died of abdominal distention (swelling or enlargement of the abdomen) due to severe malnourishment in June this year.

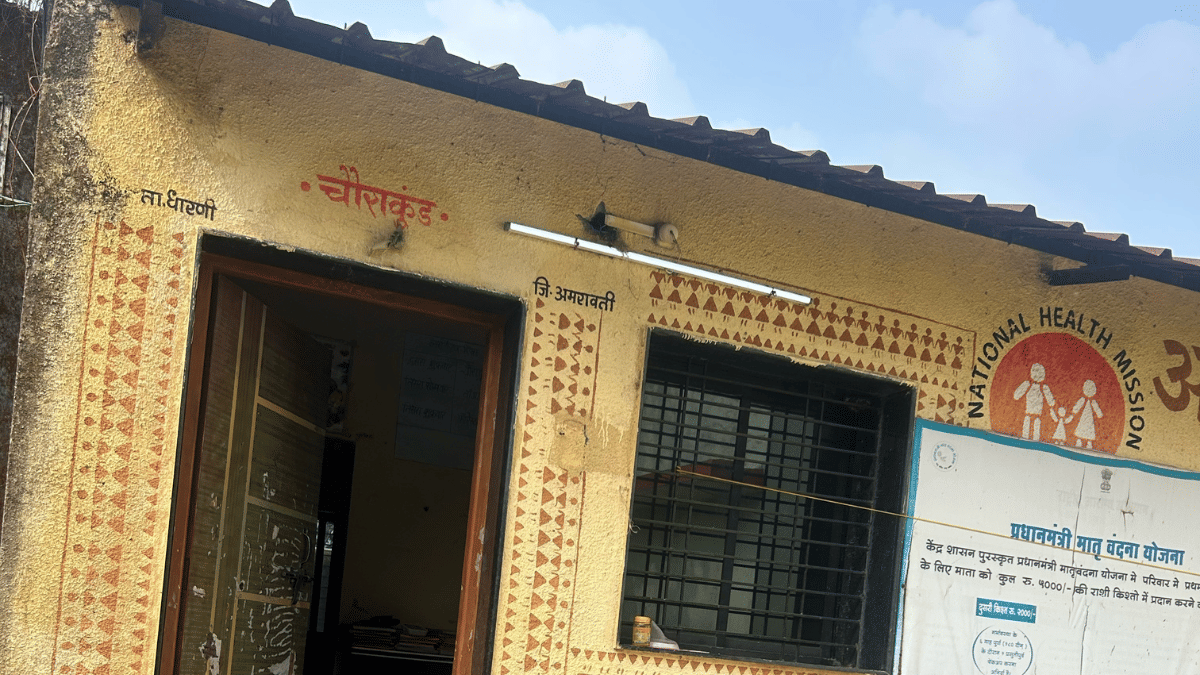

On the other side of the Satpura mountain ranges, Tara Sawarkar in Dharni taluka’s Chaurakund village lost her one-month-old in September due to pneumonia and hypoglycaemia.

This is the story of the mothers in Melghat, a region in Vidarbha’s Amravati district, located at the border with Madhya Pradesh and home to a 2,768-square kilometre protected tiger reserve.

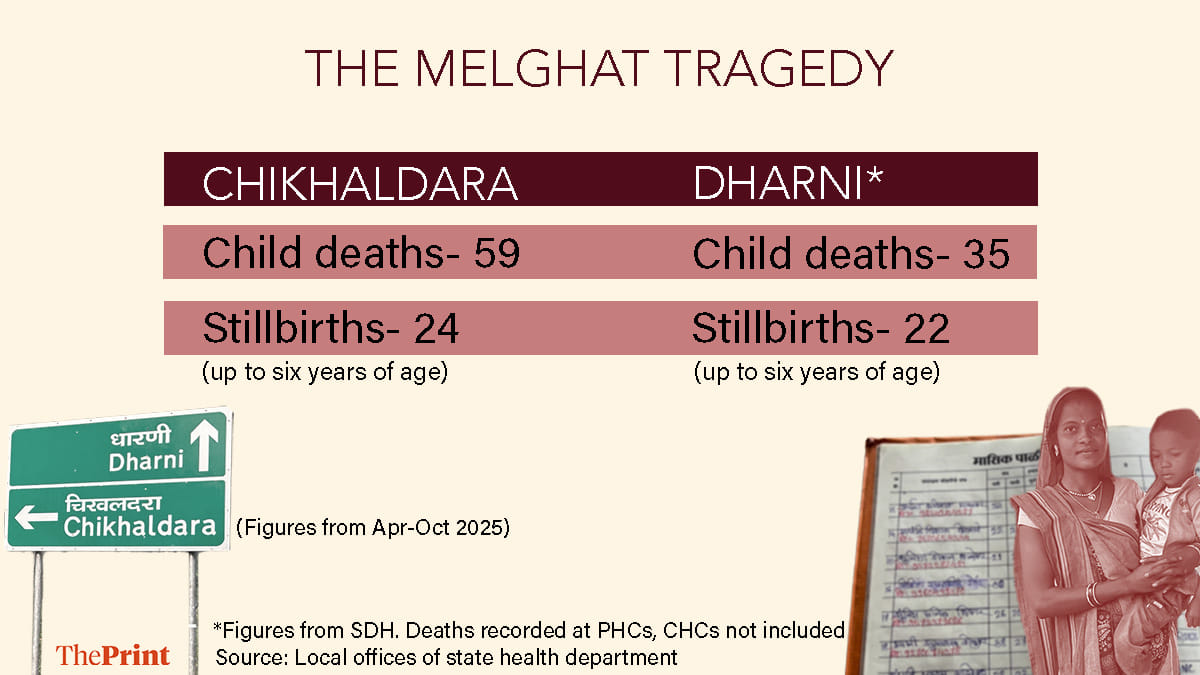

In this region comprising the Chikhaldara and Dharni talukas with unending tracts of hills, winding potholed roads, deep ravines, erratic electric supply and negligible cellular connectivity, at least 94 children (up to the age of six) died and 46 were stillborn since April.

Figures for Chikhaldara are from the office of the taluka health officer and include all child deaths registered within in the taluka. For Dharni, the figures are from its sub-district hospital, and do not include deaths recorded at PHCs and sub-centres therein.

Doctors practising in the area said the number of deaths is stark despite institutional deliveries having significantly increased over the years.

“The problem is, how can you draw water if the well itself is empty? The mothers themselves are in poor health, and as a result, so are their children,” said Dr. Chandan Pimparkar, the taluka health officer for Chikhaldara, who has been practising in the hills of Melghat for eight years.

These mothers are mainly from the Korku tribe, accounting for 80 percent of Melghat’s population, and most are severely anaemic. Doctors say, the average haemoglobin levels of women in Melghat hovers around 7-8 grams/dl as against the 12-15 grams/dl considered normal for adult women. In case of pregnant mothers, the levels are even lower at 5-6 grams/dl.

With child marriage rampant, many young mothers become pregnant far too frequently, often with only a few months between pregnancies. Whether pregnant or nursing, these mothers follow their families with their little children in tow to distant towns across Maharashtra and toil away in brick kilns more than half the year, taking a huge toll on their nutrition.

“A lot of times, pregnancies are reported late because of this annual migration,” said Avita Belsare, who has been working as an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) in the Kulangana village since 2018. “Sonographies are delayed and women do not get the necessary rest or nutrition because of the migration pattern.”

What makes matters worse is the woefully inadequate medical infrastructure, the many vacant posts with doctors often considering Melghat a ‘punishment posting’, and the wide chasm—language, culture, choices—between the tribal population and the public health officials serving in the area.

Over the past decades, multiple public interest litigations have been filed in the Bombay High Court over the high number of child deaths in Melghat, and the matter has been heard by different benches. Litigators accept that the absolute number of child deaths in Melghat has come down, but the frequency is still alarming.

This month, a bench of justices Revati Mohite Dere and Sandesh Patil pulled up the state government, calling its approach “extremely casual”, and terming the deaths “horrific”.

It has now directed a delegation of senior government officials, including public health secretary Nipun Vinayak, tribal development secretary Vijay Waghmare, and women and child development secretary Anup Kumar Yadav, to visit the Melghat region on 5 December and submit a report by 18 December.

“Problem is, how can you draw water if well itself is empty? Mothers themselves are in poor health, and as a result, so are their children,” Dr. Chandan Pimparkar, taluka health officer for Chikhaldara.

“The matter first went to court in 1993 (when a PIL was filed) and there was an order passed on the PIL in 1997, giving some specific directions on what can be done to stop children from dying in Melghat,” said B.S, one of the petitioners in the case who runs Khoj, a non-government organisation headquartered just outside of Melghat

“Since then, there have been many such visits of officials and politicians. CMs have come, governors have come. There are 13-15 research reports compiled on the problems with recommendations. But, somehow, we have not been able to stop child deaths,” he added.

The matter needs a holistic approach, with all departments working together on the ground to improve physical, social and medical infrastructure, Sane further said.

“With most deaths being from the Korku tribe, a targeted plan keeping in mind the Korku community, its language, culture, education and social status will go a long way in addressing the problem,” he said.

Also Read: More ally vs ally drama ahead of local polls: All Sena ministers except Shinde skip cabinet meet

The cost of migration

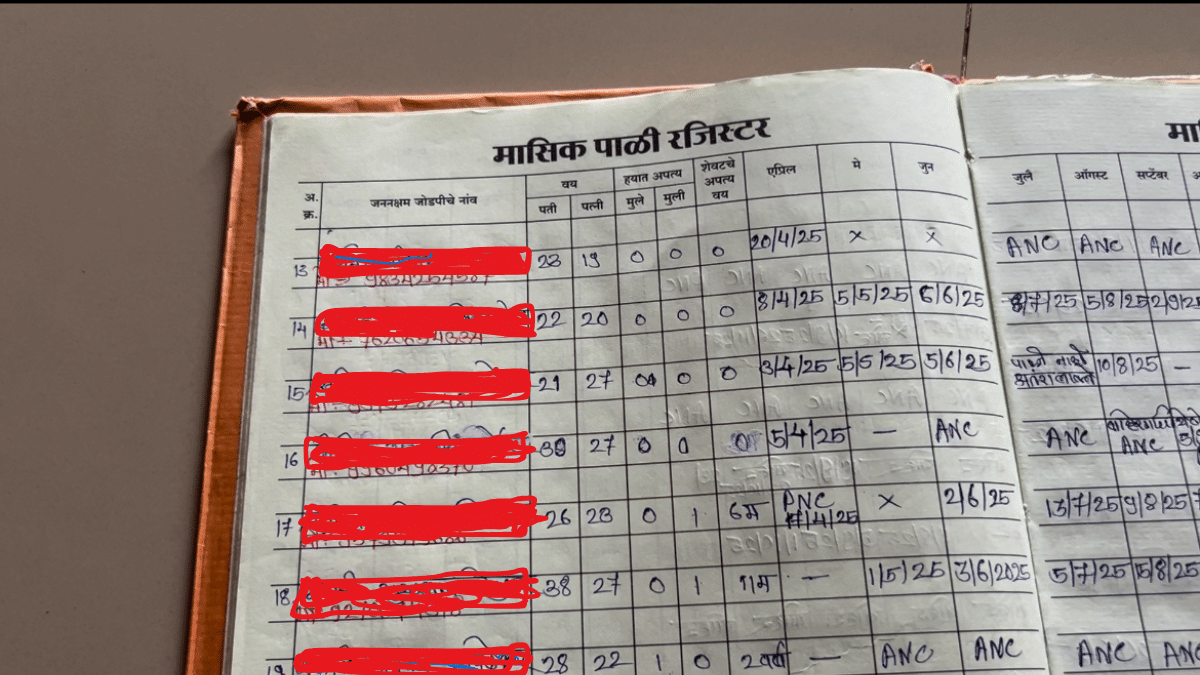

Avita Belsare, like many “Asha tais (elder sisters)” in the area, maintains a register of the menstrual cycle of every woman in the village. She painstakingly calls every woman around the date of her expected period to know if it has started. If it has, she notes down the start date in her register, setting a reminder to call her again on that date next month. If it hasn’t, she advises her to visit the health centre and take a test. She persistently keeps calling and counselling till the woman obliges.

This is how Belsare found out that 22-year-old Anjali Kasdekar was pregnant with her second child when her first one was just 19 months old.

“She had taken her son with her to a brick kiln to work. I called her and asked, “baai tumko pali aai kya?’ (Has your period started?) She said ‘no’. It had been 1.5 months since her last period,” Belsare said.

She kept on calling Anjali for the next 15 days, urging her to come home, visit the hospital, and if she can’t, then at least take a urine pregnancy test.

“She stretched this for two months. She didn’t visit any doctor there. She just took a urine pregnancy test, which was positive. She eventually listened to me and came back to Kulangana to register her pregnancy with the local Primary Health Centre (PHC), and did the initial tests. She was carrying twins,” Belsare said.

The very next day, Anjali went back to the brick kiln and returned well after her fourth month. Close to her seventh month of pregnancy, Anjali fell sick with a disturbing cough and cold and delivered her twins prematurely at the local sub centre.

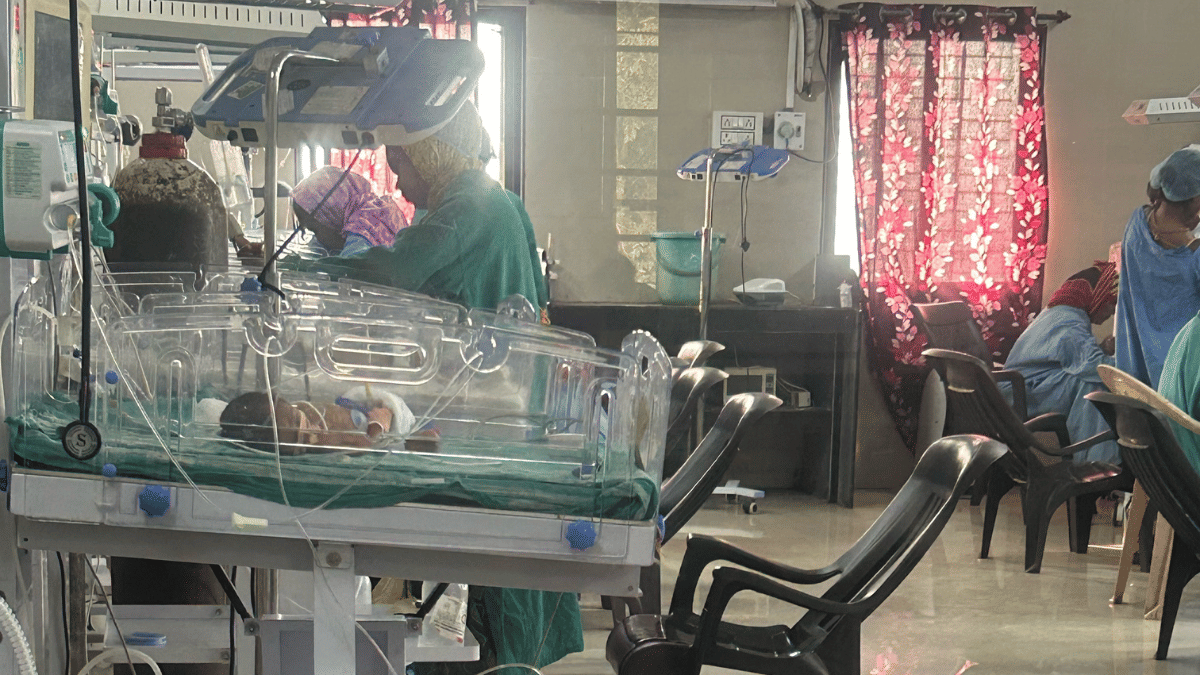

The premature babies with a low-birth weight had to be shifted to a neonatal care facility in Achalpur in the Amravati district, but one of them, who Anjali would lovingly call ‘Balya’, did not survive.

In less than three months since the tragedy, Anjali is now back at the brick kiln with her husband, as well as her 2.5-month-old prematurely born baby.

As such, agriculture is the main economic activity in Melghat. The region, with 324 villages and a population of 3.24 lakh, as per a zone survey conducted by the Amravati district authorities in 2011, gets good rainfall during monsoon.

Farmers with tiny landholdings sow just one crop a year—sometimes soybean, sometimes maize—during the rains. The income it generates is meagre and insufficient to last them the whole year. So at the end of the monsoons, families migrate in search of work.

“When our people migrate for work at the brick kilns, it is a very tough life. They put in long hours to maximise their wages. Food, nutrition, health, shelter become inconsequential topics there. And in any case, it is arduous work for a woman to be doing during her pregnancy and postpartum,” said Usha Belsare, a Melghat native who belongs to the Korku tribe, and is now a social worker with Khoj.

In 2021, the Bombay High Court appointed Dr. Chhering Dorjee, who was then posted as special inspector general of police in Nagpur, to visit the interior tribal villages of Melghat and submit a detailed report on child deaths. Dorjee camped in Melghat for seven days and submitted a comprehensive 36-page report, highlighting migration as one among the major reasons.

His list of suggestions included putting in place a mechanism ensuring that pregnant women migrating for work are able to continue taking nutritional benefits from any a nearby anganwadi centre.

Under the ‘Amrut Ahaar’ programme of the Integrated Child Development Scheme, the state government sets aside Rs 45 for every eligible pregnant and breastfeeding mother to get a full meal from anganwadi centres. The meal comprises three chapatis or two bhakris, rice, a peanut laddoo, one egg or two bananas, a green leafy vegetable, five spoons of edible oil, salt and masalas.

Children up to six years of age also get supplementary nutrition at anganwadis.

Dorjee’s report and recommendations were discussed in the chief secretary-led Mission Melghat committee, which was set up in 2019 as per the directions of the Bombay HC. However, very few of them have taken shape on the ground.

For instance, at a meeting in February 2022, the Mission Melghat committee decided to give every woman a migration card as a pilot project to track her movement and her health status.

“There is still no mechanism on the ground to ensure that a pregnant woman is getting the nutrition and vitamins needed when she migrates,” said a medical officer working in Melghat, who did not wish to be named.

“We have had the Union government’s ‘Poshan Tracker’ app, but it hasn’t taken off very effectively in Melghat, and is not integrated with the public health department for us to have the data of where a woman has migrated to, whether she has taken her children along, and whether they are being monitored by any anganwadi there,” said a medical officer working in Melghat, who did not wish to be named.

The Mission Melghat committee has had 16 meetings until now. There’s another ‘Gabha committee,’ also set up under the chief secretary in 2013, to look into child deaths in tribal belts across Maharashtra. The Gabha committee has had 31 meetings so far.

Lack of local employment opportunities

In March 2021, Pramila Belsare from the Girguti village in the Chikhaldara taluka gave birth to a healthy boy, weighing 2.8 kilograms, at the local Tembrusonda PHC. For the next four years, she migrated every year close to Amravati city with her husband and their son Aatish to work in a brick kiln.

Pramila and her son’s nutrition suffered and the healthy infant that Aatish was, grew into an impoverished toddler.

At four years and three months, his weight is a measly 9.7 kgs as against the average 16.7 kgs that boys his age weigh. In June this year, Aatish died with an abdominal distension. “We have no idea what she used to feed him, or what she herself ate,” Pramila’s brother-in-law Harichand Belsare said.

Families in Melghat take loans before the cropping season and need to repay them. The brick kilns yield decent money.

“On an average, those who migrate and work in the brick kilns come back with about Rs 40,000 to Rs 60,000 in the 6-7 months that they are there. Some families with more members working in the brick kilns also make up to Rs 1 lakh,” Harichand said.

In his 2021 report, Dorjee had highlighted the need to create employment opportunities within Melghat so that the local population doesn’t need to migrate for work.

“There are various government schemes in these areas, work related to gram panchayats, forest, agriculture, horticulture etc where people could be provided with enough work opportunities to earn his/her livelihood. The provision of employment to these vulnerable groups will not only ensure them monetary benefits but also proper antenatal healthcare services along with provision of free nutritional supplements at anganwadis,” the report, accessed by ThePrint, said.

Residents say, there is work available now under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and at Rs 312 per day, the wages are not bad either. But, most villagers don’t prefer to take up these works as payments are often delayed.

The state public health department also has a ‘Budit Mazoori Yojana,’ a scheme to compensate for the loss of work, for pregnant women from the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and those below poverty line.

Under the scheme, eligible women can get Rs 2,000 per month from the seventh month of their pregnancies. However, there is barely any awareness on the ground about the scheme, and it also doesn’t solve the problem of heavy manual labour and missed nutrition in the early months of pregnancy.

“Also, in many cases, working at the brick kilns has become a form of bonded labour. People borrow money at a low interest rate from the (brick kiln) owners, and have to return to the kiln to work and pay off the debts,” Sane from Khoj said.

He added, the development of tourism around the Melghat Tiger Reserve hasn’t massively helped the local population in terms of employment and other economic opportunities. “There are a few stray examples of home stays and tribal village experiences that have been developed, but that’s where it ends.”

In the poverty-stricken Melghat, nutrition is sub-par even among those pregnant women who do not migrate. Addiction to tobacco and local liquor is rampant, and supplementary nutrition at anganwadis is given as take-home ration, and often ends up being distributed among family members. The Dorjee report had also noted the two points and recommended action.

On Thursday last week, Dr. Pimparkar had just returned from a field visit to one of the villages under his jurisdiction. He met a pregnant woman working in the field and chewing tobacco.

“She told me she feels hungry all the time. The tobacco, she said, helps kill her hunger. When I asked her about her supplementary nutrition, she said ‘she shares it with her husband’. He eats before her, and then she takes what’s left,” Dr. Pimparkar said.

Cultural chasm, mistrust, & avoidable deaths

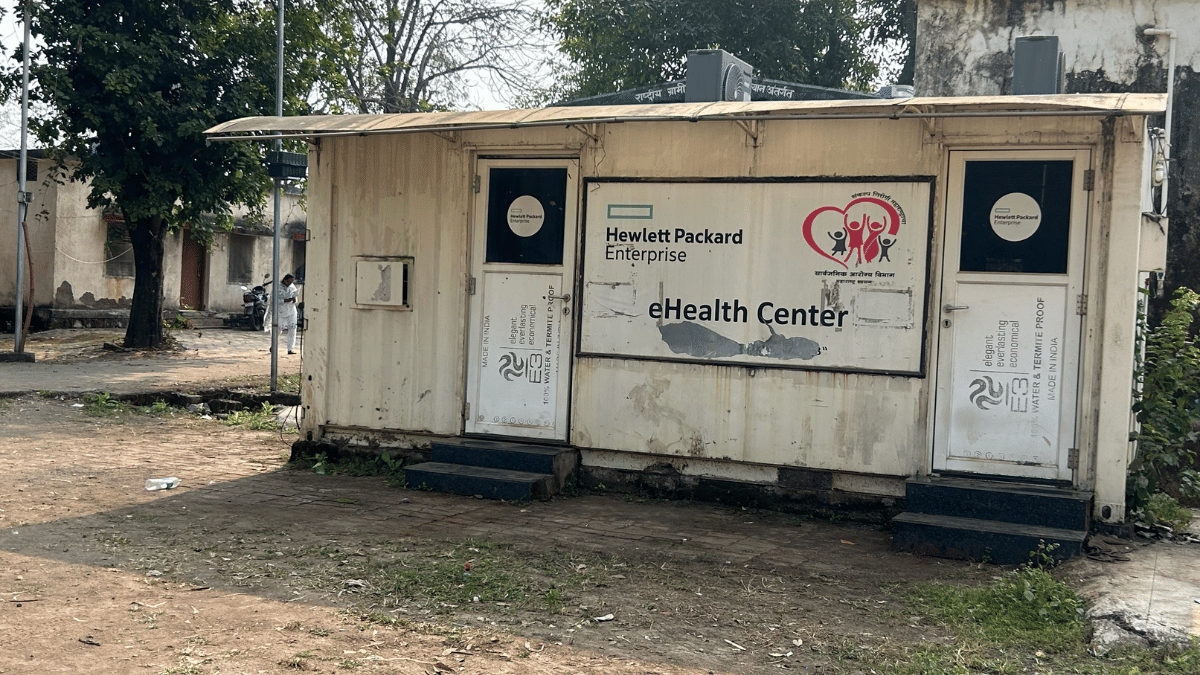

From April this year, the PHC at the Dharni district’s Harisal village—among India’s first digital villages where almost every digital intervention, including one telemedicine service installed by Hewlett Packard, has now broken down—has recorded eight deaths of children under the age of six.

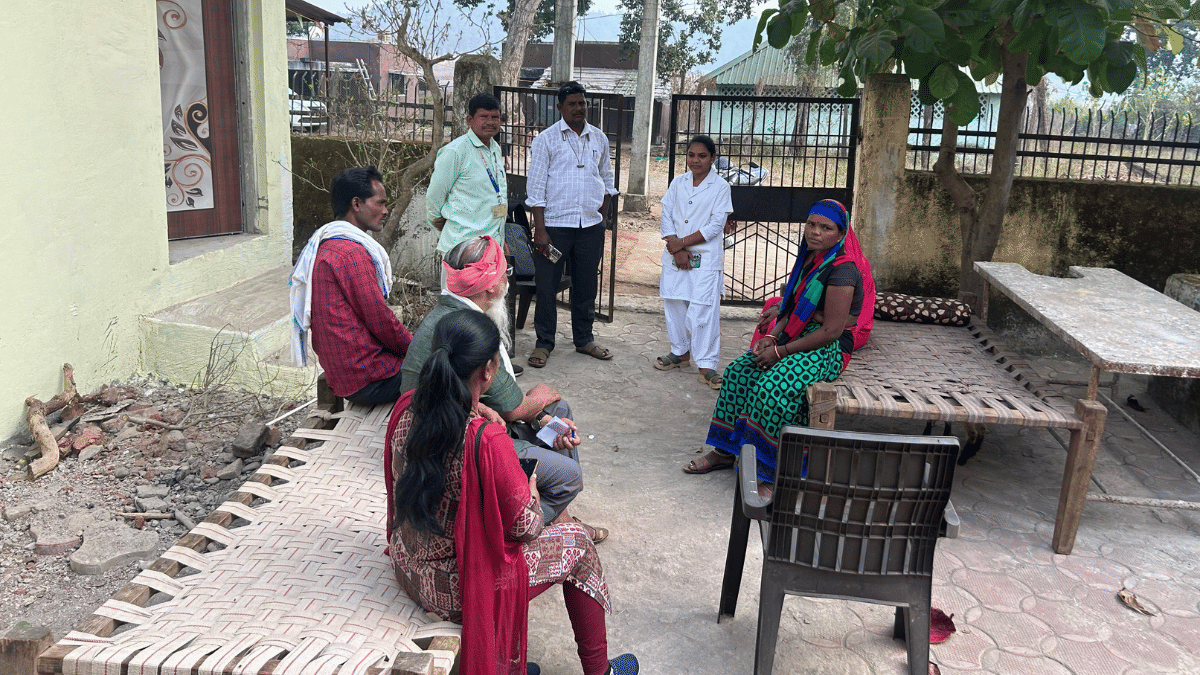

The taluka health officers of both Dharni and Chikhaldara hold reviews of the reasons behind child deaths in their jurisdiction and make remarks as a learning for the future.

According to the remarks on the Harisal deaths, accessed by ThePrint, three of the eight tragedies could have been avoided with “proper counselling.” In a fourth case, the parents had refused treatment. In other cases, the staff had identified the need for an anomaly scan and early referral as lacunae.

Culturally, and linguistically, there is a wide gap between the members of the Korku tribe and the public health staff, often deputed from outside Melghat. If a family loses one child during birth at a hospital, they are hesitant to go there for the next delivery.

For instance, in Anjali’s case from Kulangana village, her husband knocked at Avita Belsare’s house late at night the day one of their twins died.

“He shouted at me and solely blamed me for the death, saying his son would have still been alive if I had not taken Anjali to the main hospital at Achalpur,” Avita said.

The Korku community believes in ‘bhumkas,’ members of the tribe who identify themselves as healthcare practitioners, but believe in occult ways.

“If it is a minor cough, cold or fever, the villagers don’t mind approaching a local doctor. But if it is something even slightly more serious, like if the child is having coughing fits or convulsions, they think it is something else and turn to Bhumkas, who often give diagnoses such as the child is possessed by a spirit,” said Dr. Vaishnavi Harne, medical officer at the Harisal PHC.

The local public health machinery has travelled the distance from absolutely rejecting the Bhumkas to eventually understanding their importance in the Korku culture. While doctors, with the help of Asha workers, still try their best to convince patients not to approach Bhumkas, they have also started holding workshops for groups of Bhumkas to sensitise them on basic medical practices and the need for referrals to health centres or hospitals.

Doctors said such workshops are yet to show any tangible results, but it is a step to bridge some distance.

Some practitioners such as Dr. Pimparkar, who comes from nearby Buldhana district, have gone the extra mile and learnt the language of the tribe. But, a lot is still lost in translation, leading to distrust. Some straightforward cases often result in extremely unfortunate avoidable fatalities.

On Thursday last week, Tara Jawarkar from Dharni’s Chaurakund village, very hesitantly recalled the story of how she lost her daughter, born on 12 August this year at a healthy weight of 2.5 kgs, within 20 days.

On the advice of the village’s Asha tai and the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) at the local subcentre, Jawarkar ensured that she took her folic acid and calcium tablets throughout her pregnancy, completed her sonographies and had an institutional delivery at the sub-district hospital at Dharni. Then, she went to her mother’s village.

“Every time I tried to breastfeed, the baby would bite my nipple hard. The baby wouldn’t defecate for four or five days on end. I knew something was wrong,” Jawarkar said, adding she did consult a doctor about it. Then one day, while she was on the way to see a Bhumka, her daughter died.

Doctors noted pneumonia as the official reason, but Indu Bilawalkar, the ANM who has been recruited from the local Korku community, said doctors had mentioned the baby was hypoglycaemic (a condition where blood glucose levels are abnormally low), and wasn’t getting enough glucose as breastfeeding was difficult.

Jawarkar’s was one of the three cases where the Harisal PHC had marked the need for “proper counselling”.

For a couple of years now, doctors in Melghat have been following a ‘Mission 28’ plan, where the aim is to check on a pregnant woman every single day for 28 days before her delivery is due, and for 28 days after her delivery. It is mainly to avoid losses like the one Jawarkar had to suffer, and increase institutional deliveries.

Dr. Harne was confident that Jawarkar could have got the necessary help on time had she been in Chaurakund after her delivery. “She went to another village because of which our Asha workers weren’t able to reach her,” she said.

The ‘Mission 28’ plan, she said, has helped contain infant deaths due to another unfortunate cause—milk asphyxia.

“When I joined last year, I came across a case where a woman who had delivered a healthy baby a few days ago fed him and put him to sleep in a makeshift swing. She had no help and got busy with housework. The child choked on his mother’s milk and died. Since then, I made it my mission to tell all Asha tais to counsel every patient properly about the importance of holding a child upright and burping a baby after feeding,” Dr. Harne said, adding that so far this year, there hasn’t been a single death due to milk asphyxia under her jurisdiction.

But, overall in Melghat, infants are still dying due to milk asphyxia.

In Chikhaldara taluka, five of the 59 child deaths up to six years since April were due to milk asphyxia. The corresponding figures for Dharni were not immediately available.

A loss-making ‘punishment posting’

It’s an open secret that doctors look at Melghat as a punishment posting, and the reasons for that go beyond the basic hardships they have to face in a tribal area with a thick forest. Snakes and scorpions are commonplace in houses and health centres, and negotiating the bumpy roads, poor power supply and cellular connectivity is tedious. But, going beyond all of that, the low budgets and delayed payments make it tough for doctors to function.

At about 9 am at the Seemadoh PHC in Chikhaldara last Thursday, a woman was stirring rice and dal together in a big pot to make khichadi. Just half an hour ago, she had finished making over 50 small cups of tea that were being passed around in tiny paper cups to patients and their family members. The PHC had a “family planning” camp where tribal women from nearby villages who had children were being encouraged to undergo sterilisation or tubal ligation.

“There is a per patient per day budget sanctioned by the government for food, but we haven’t received the funds. This tea and khichadi is because the staff here has pooled money,” said a helper at the PHC who did not wish to be named.

The staff has also shelled out money to arrange for mattresses and blankets for patients’ attendants.

The government commits Rs 200 per patient per day, which is too little to cover the costs for the patients’ and their relatives’ travel, food, and stay, a PHC staff member said.

“For the family planning camp, we had to call a surgeon from outside on three occasions. The government sanctions Rs 200-300 for the fuel expenses to get a surgeon here. This rate was fixed many years ago and has not changed though the price of fuel has gone up. The distances and bad roads in Melghat make ferrying of surgeons an expensive venture. We have spent Rs 1,600 per trip for the surgeon on three occasions. That’s Rs 4,800 straight out of our pockets,” the staffer said.

All of a sudden, the electricity conked off and the generator had to be switched on, the fuel for which, the staff said, was arranged by them. They cannot risk power going off in the operation theatre.

Dr. Mahendra Nade, the medical officer of the PHC who has been in Melghat for eight months, has already spent Rs 37,000 of his own money on such sundry expenses. “Some of it will be reimbursed when the government releases the budget, but all doctors who have served in Melghat have had to write off some money,” he said.

The harrowing working conditions mean no doctor wants to take up a job in Melghat, and while the workload is heavy, at any point of time there is a high number of vacancies.

For instance, the Seemadoh PHC is supposed to have seven subcenters under it, of which one is not functional. Every subcentre should be led by a community health officer, but the post is vacant in three of the six fucntional subcenters.

It’s the same story in the Harisal PHC. There are 10 subcenters, five of which do not have community health officers.

The 50-bed sub-district hospital at Dharni caters to about 150-200 patients at any point of time. Sometimes, the doctors there say, they have to discharge patients earlier than ideal simply because there is no place to accommodate new patients.

“A second 50-bed hospital was sanctioned on the adjacent plot in 2021-22. We have also been allotted the land on paper, but there is a veterinary hospital there that first needs to be shifted and the budget for that has not been sectioned yet,” said Dr. D.B. Jawarkar, the medical superintendent at the hospital.

In the first 15 days of November itself, the Dharni sub-district hospital recorded deaths of two newborns and one pregnant woman. There are medical reasons attributed to each incident on paper, but Dr. Jawarkar is struggling to make peace with these deaths.

“In medicine, there are times when there are regrettable, unexplained deaths. Such things happen sometimes, but they cannot happen all the time,” he said.

Meanwhile, in the hills of Melghat, the grief of mothers is so frequent and so commonplace, that it has numbed the sting.

In Jamli Aar village last Wednesday, Meena Patve, the local Asha tai, knocked on Kiran Kasdekar’s door. Patve wanted to record some details about her three-month-old baby, Kaveri’s death. “Tera hi baccha mara na? (It was your child that died?),” Patve asked, shouting from outside the door.

With a demure smile, Kiran walked out with her three-year old son and nodded.

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: After SC rap, Maharashtra brings compensatory afforestation policy—12-ft saplings, geo-tagging

Extremely important read. The sheer lack of funds and infrastructure at local PHCs and sub-centres is alarming, given so many State policies exist in place. This is the primary reason that evades trust within communities, making the job of ASHA workers tougher, and deters people from seeking treatment at local hospitals. The migration aspect has also highlighted aptly, for people need local jobs if the entire ecosystem is to function in tandem.