The Chinese recently let it be known to the world that they are finally going to implement their plan—which some might call a fantasy, but the Chinese are known for such ambitious endeavors—of damming the Brahmaputra river on their side of the watershed in the Himalayas, where it is called the Yarlung Tsangpo. The Yarlung Tsangpo is a powerful river.

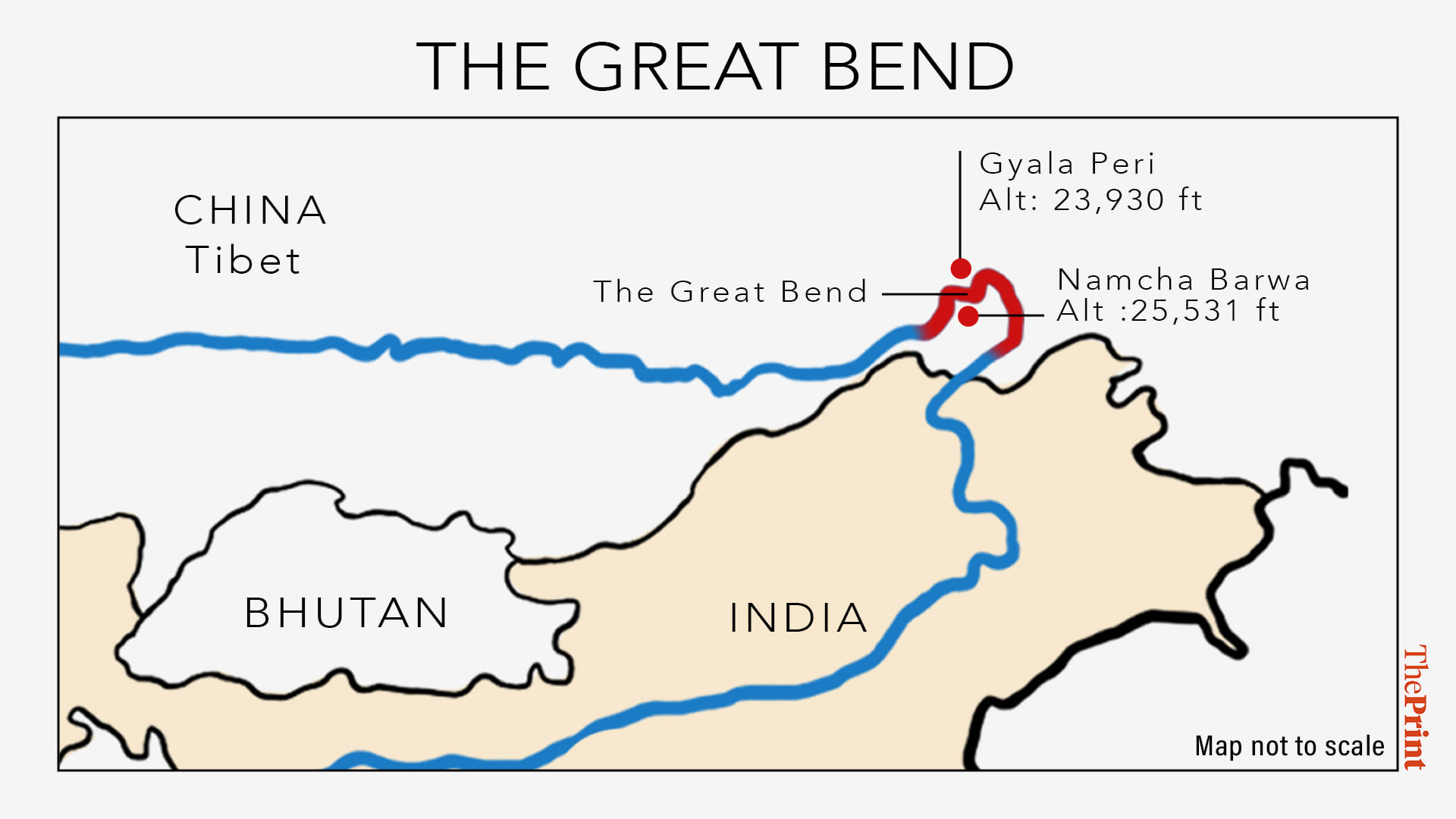

The important thing, it flows through what is known as the Great Bend, the Great U-turn, or the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend. The geography of this area is awe-inspiring.

The bend provides what may be the most perfect terrain and geographic conditions for building a power-generating dam. Hydroelectric power generation relies on water falling from a height. The steeper the gradient, the more power can be produced.

The Chinese now plan to dam the Brahmaputra at this bend. How much power do they aim to generate? Sixty gigawatts of power—60,000 megawatts. That is a massive amount of energy, and they argue it is crucial for meeting their net-zero targets by 2030.

Now, the fact is that the Chinese already have too many big dams. The Chinese at this point have more than 87,000 dams of some considerable size across their country. China’s rivers are the most dammed in the world. So, nobody is quite convinced that the Chinese need this power. They think they can dam anything, link any river, and construct anything.Everything has to be the biggest, the largest, the deepest, the widest and the fastest, most important. Look at their trains right now. So, the Chinese have great faith in their engineering and they think they can do it.

Now, that has immediately caused concern in India for multiple reasons. One, what does it do to our water security because China is the upper riparian? Upper riparian is the country that is first to receive the water of a river or, or which is ahead of others who might receive that water next to it. So, India is a lower riparian to China in this case. Similarly Bangladesh is an even lower riparian to India.

And that is something that we see coming up all the time with the Nile river. This is always an issue with multinational rivers. So, Nile river, funnily or ironically, Egypt—the country at the end of the river—exploited the waters most of all. And Egypt had the privilege of doing it in comfort because the poorer and the more backward African countries from where the river actually emerges, including Sudan, for example, they didn’t quite have the wherewithal to make use of the water that was flowing out of there.

India faces similar issues with Pakistan over Himalayan rivers, regulated by the Indus Waters Treaty. The treaty grants Pakistan full rights over the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers, while India retains control over the Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.

We can use all of that water. We are the upper riparian to Pakistan, and it’s up to us how much water we want to let go into Pakistan. There is no obligation. However, remember that for some of those, the upper riparian, or if I may say the uppermost riparian, is still China because Satluj and Indus come from Tibet.

Also Read: India protests China’s 2 counties in Aksai Chin, expresses concern about proposed dam on Brahmaputra

Tibetan plateau & Brahmaputra

Tibet is the greatest source of river water in the entire world. Some of the biggest rivers emerge from the Tibetan plateau. I will list these for you. These rivers are all multinational rivers. These rivers include the Brahmaputra (China, India, Bangladesh), Indus (China, India, Pakistan), Sutlej (China, India, Pakistan), Karnali (China, Nepal, India), Nu (China, Myanmar, Thailand), and Mekong (China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam). Only the Yangtze River, which also originates in Tibet, is entirely within China.

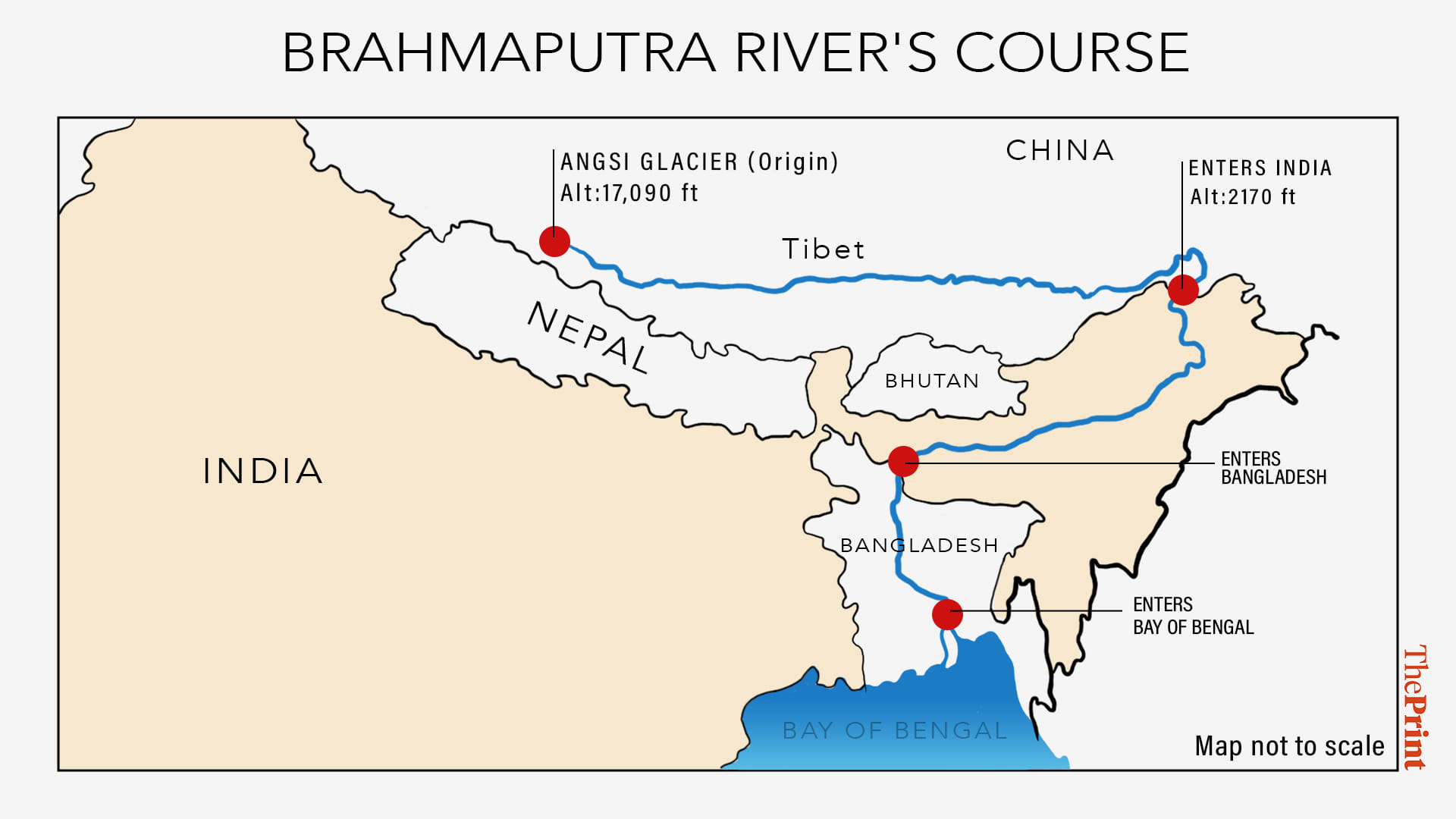

The Brahmaputra is called Yarlung Tsangpo in China. It does not turn a short length in China and see how it runs. It’s not running north to south. It’s actually running west to east. It emerges at the foot of Mansarovar at an altitude of 17,400 feet, making it one of the highest rivers in the world. In places, it’s also the deepest. It creates some of the deepest or longest canyons in the world, which is where the bone of contention lies.

But I will come to that as we journey along this long route.

The river flows approximately 1,700 km through the Tibetan region of China, about half of India’s total border with China, before entering India. That is the other side of the Himalayas or if you might say, or the other side of the watershed this river runs. The important thing is, this river has a very steep gradient. And then it comes into India.

If you go to Dhubri [in Assam] and see how it enters Bangladesh, you can see its shape, size changes all the time. It is a nightmare for anybody to figure out where the border is because this is also a braided river. Braided rivers have multiple channels that shift seasonally, creating islands from silt deposits. So, Bramaputra is a braided river and that is why sometimes it becomes difficult, particularly in the plains to figure out its width and its length in terms of where it is ending. That said, about 1,700 km in China, about 1,000 km in India and about 300 km in Bangladesh.

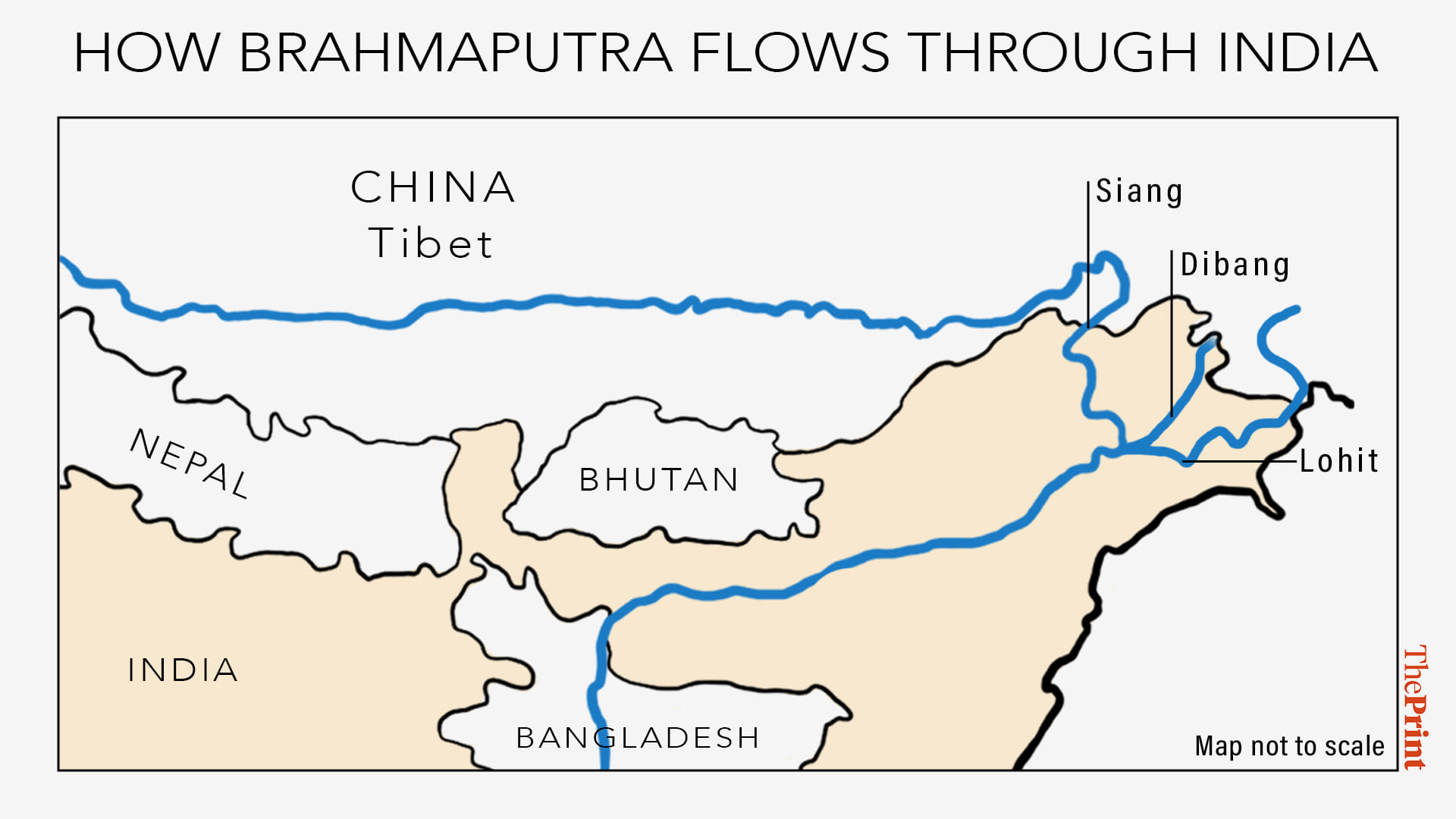

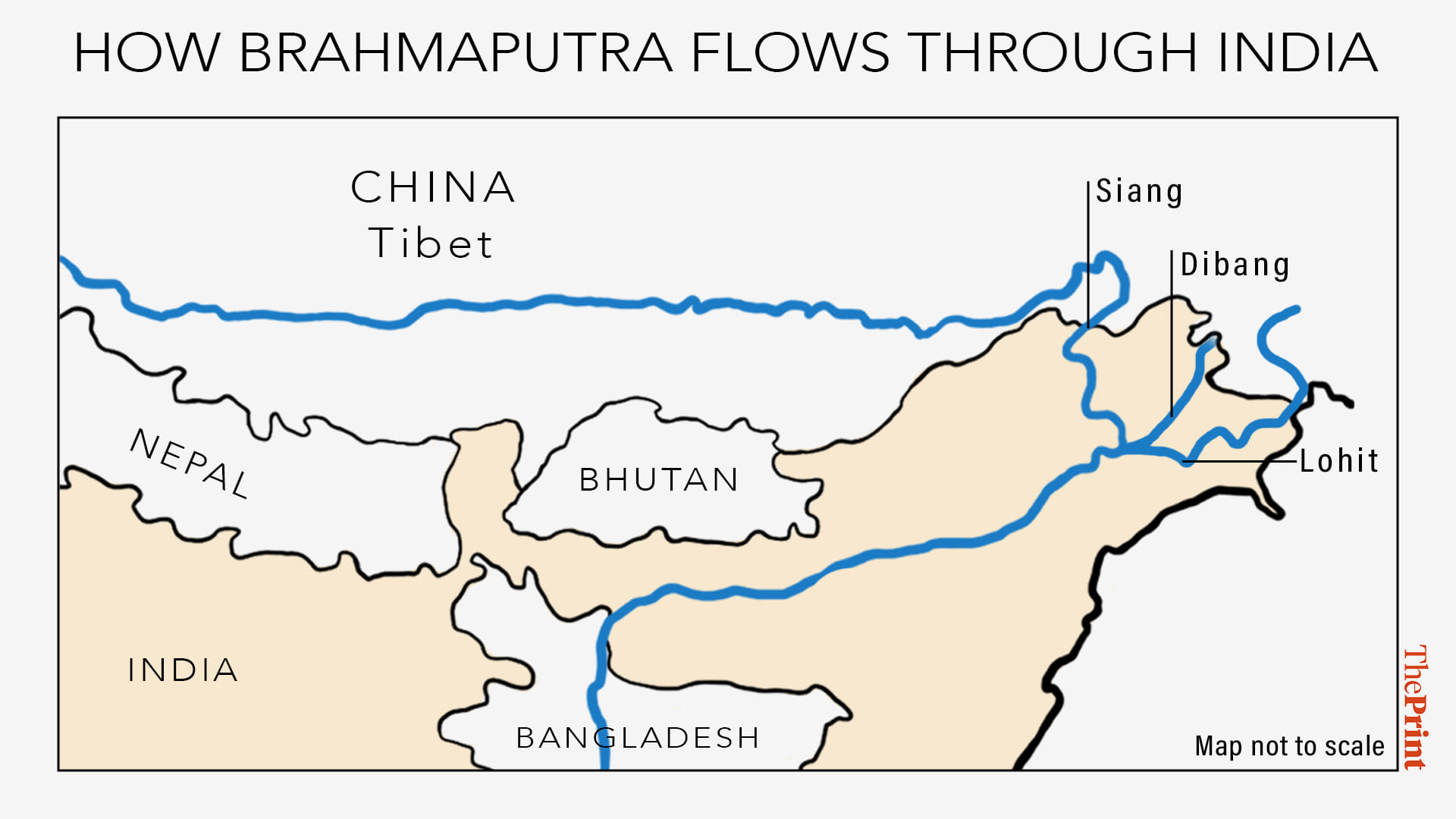

As it goes into Bangladesh, it changes its name. In China, it is called Yarlung Tsangpo. As the river enters India, it is known as the Siang or Dibang before becoming the Brahmaputra. So, Siang comes down, there is still some gradient available.

That is why the Government of India, in fact, right from the UPA era—it is an idea that precedes even the UPA era—but UPA first did the detailed project reports, allocated money and then as happened with many projects under the UPA, this got stopped also because of environmental concerns. This is when Jairam Ramesh went to the Northeast, held a town hall with activists and others. And after the town hall, wrote a letter to the Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh saying that these projects should not be rushed because if they are rushed, local people may get angry and they may also get more inclined towards China.

So, in any case, this project didn’t move. The Modi government now has been trying to move it. So, this project because some gradient is still available in Siang, this is called Upper Siang hydroelectric project. This also is supposed to produce 11,000 megawatts. But with the capacity of 9 billion cubic metres of storage, the estimated cost would be Rs 1.13 lakh crore.

Also Read: Pictures show it’s time to question China’s alibi on Brahmaputra pollution

Mega Chinese project on Brahmaputra

What the Chinese are planning is the world’s largest hydroelectric project by far. How large? It is three times the size of the next largest project also built by the Chinese. It would generate three times the power of the Three Gorges Dam, China’s current largest hydroelectric project, which produces 17 gigawatts. The Three Gorges Dam submerged cities, displaced 1.4 million people, and caused a significant environmental impact. In fact, it was going to sink two cities, 114 towns and 1,680 villages, which it did.

This new dam, planned on the Great Bend of the Brahmaputra, would far exceed that scale. The river drops dramatically in altitude within China, descending from 17,400 feet at its source to 2,900 metres (9,500 feet) and eventually to 660 metres (2,170 feet) before entering India. The potential for energy generation is unparalleled, but so are the risks and geopolitical implications. So, this is truly a mega project.

As it emerges from behind the Mansarovar massif, it begins at an altitude of nearly 17,400 feet. Then, as it travels down through Tibetan territory, still under Chinese control, it descends to 2,900 metres or 9,500 feet. Further downstream, it reaches 660 metres or 2,170 feet. By how much altitude has this water fallen over this distance of nearly 1,700 km? I referred to a document on the Assam government’s website. This document notes that in Chinese territory, the Brahmaputra, the Yarlung Tsangpo, has an average gradient of 2.82 metres per km. That’s a significant gradient for a river.

However, the Chinese haven’t constructed anything there yet. This is because, while the gradient exists, it still doesn’t provide as much leverage as the river might offer later, particularly with advanced engineering.

In fact, once the river reaches the plains, it enters India in the Siang region. At that point, the river is at 2,170 feet or 660 meters. From there, it descends into the plains of Assam, where it becomes almost flat. Until it reaches the Bay of Bengal, its gradient is only 0.1 meters per kilometer. So, generating power is not very feasible there. That is why India is also planning its projects upstream in the Siang region, where a gradient is available.

Now, what happens to the river as it comes into India? As the Brahmaputra enters India, it is joined by two large tributaries. See this map.

These two large tributaries are Dibang and Lohit. Both come from the east, with the Lohit being slightly more to the south. These sizable rivers join the Siang river. The Yarlung Tsangpo, as it enters India, is called the Siang.

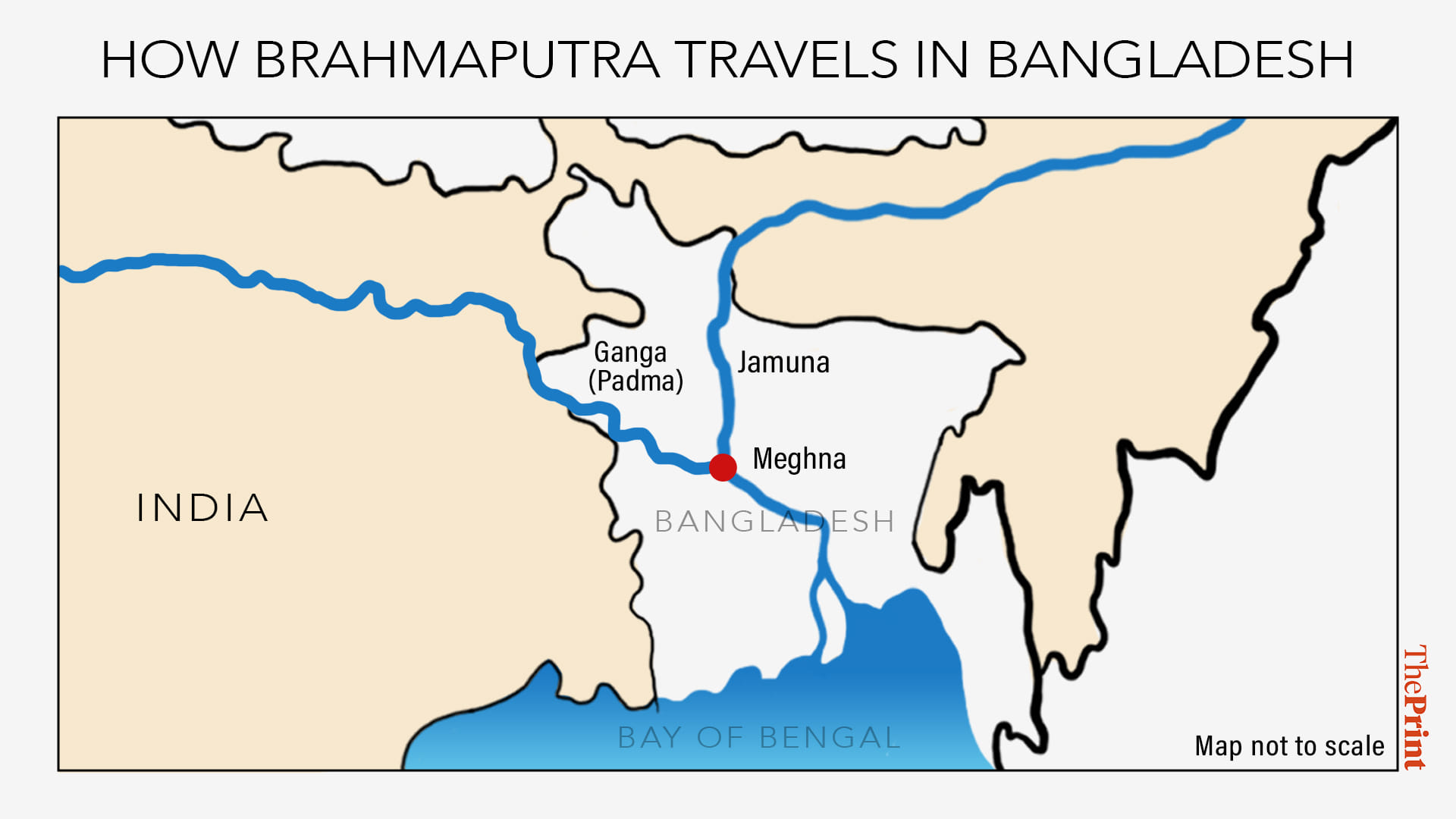

Then, these two tributaries join, and the river is called the Brahmaputra, which flows through India for nearly a thousand km before entering Bangladesh, where it is called the Jamuna. This Jamuna ultimately joins the Ganga, which is called the Padma in Bangladesh.

Once these two rivers meet, they become the Meghna.

Not many tributaries join it in Bangladesh, but there is one significant tributary worth mentioning: the Teesta river. The Teesta river has been the subject of an old disagreement between India and Bangladesh. In fact, the Bangladeshi government has often stated, as recently as in a speech by their army chief, that India should share more of the river waters, specifically the Teesta. This entire river system is part of the Brahmaputra basin.

Now, the Chinese claim that nobody will be affected by their project. They assert it is only a run-of-the-river project. A run-of-the-river project means they divert the river, drop the water from the gradient, use it to produce power, and then let the water return to its natural flow. They will maintain a reservoir of some size to ensure a consistent flow for their turbines. This reservoir would act as a backup in case the river dries up, a drought occurs, or snowmelt slows—because on the Chinese side, the river is mostly snow-fed. However, the water cannot be diverted elsewhere. It will ultimately flow back into the river system.

When you examine the river’s course, you will notice something remarkable. As the river flows eastward, it appears to go straight. Then it suddenly takes a sharp turn northward, then eastward, and then bends southward. This is the Great Bend.

The Great Bend lies between Namcha Barwa, a very high peak at 25,531 feet (7,782 meters), and Gyala Peri, which is 23,930 feet (7,294 meters). This canyon is formed between these two towering peaks. Now, consider what a humongous gorge this is. At 500 km-long, it is slightly longer than the Grand Canyon in the US. It is also much deeper—in some places, it has mountain walls 16,000 feet high on either side.

You might wonder, as I did, how such a massive canyon was formed in this area. The answer lies in the peculiar geology of the Brahmaputra. The Brahmaputra is what geologists call an antecedent river, meaning it existed before the Himalayas rose. This river flows through the tectonic boundary where the Indian and Eurasian plates meet.

As a result, mountains grew around the river, but the river itself predates them. This is also why this project carries particularly high seismic risks.

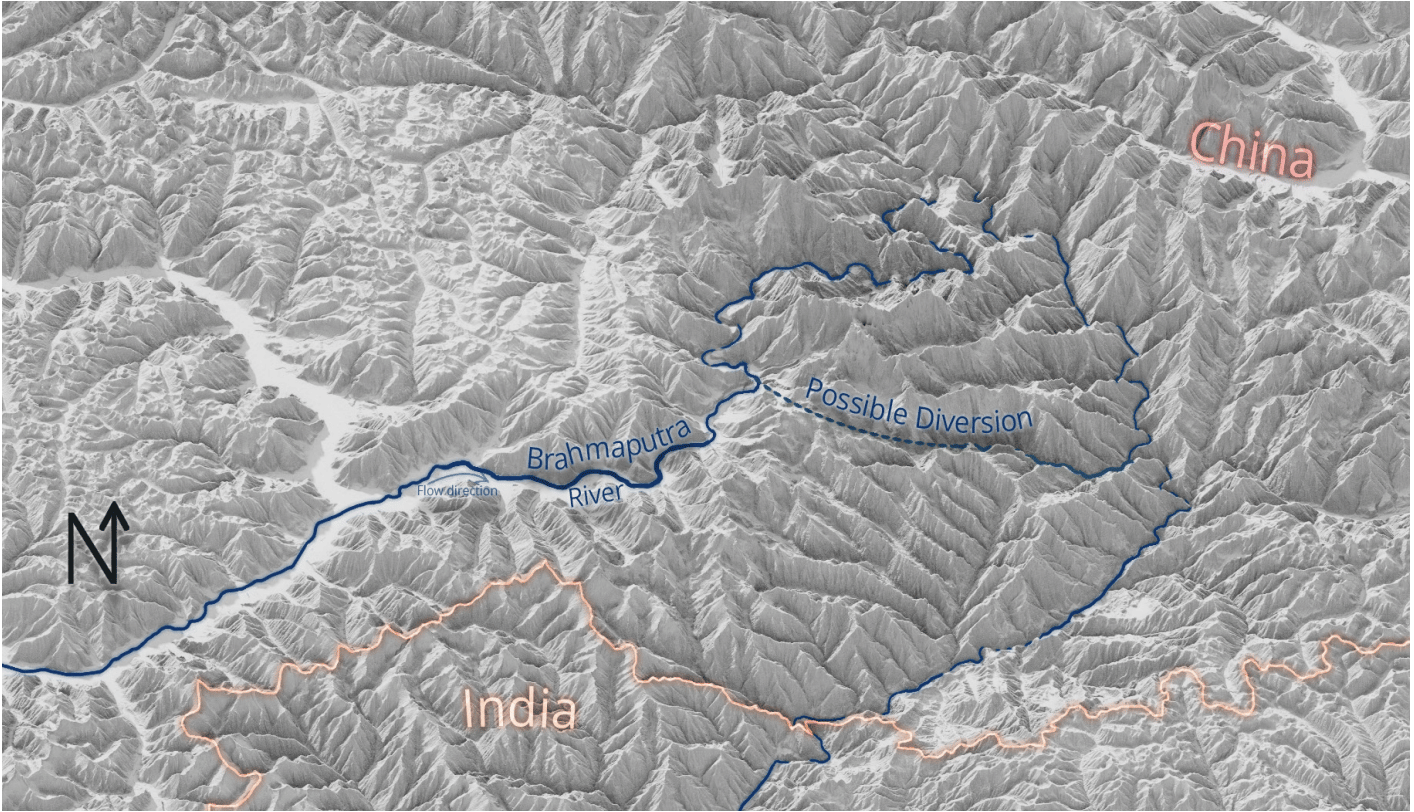

Returning to the gorge: as the water flows through the canyon, the gradient remains steep. How steep is it? If you see, this canyon is 504 km; 240 km is as it is going up to make the bend around Namcha Barwa; and the rest, about 265 km, is as it’s coming down. That gives it an average gradient of a little over 4 metres per km. It’s a lot. And yet, it’s not good enough to produce quality power, which will have a very high cost. So, what do the Chinese plan to do? This Nathan Ruser graphic we borrowed with gratitude from a Neely Haby paper. This graphic tells you a likely place where the Chinese may bore through the mountains.

So, the Chinese idea is to cut through the tall mountains in Namcha Barwa, stop the water at the 9,500 feet-level. By this time, the water has already come down to 2,900 metres or 9,500 feet. Cut it there, and build 20 tunnels. From those tunnels, we will cut across the bend.

So, suddenly, from 9,500 feet, the water drops to about 1,500 metres or 4,900 feet. That is a very steep gradient. Once you have water going through these tunnels at that pace, with so much gravity and so much energy coming in, and your turbines are at the other end of it, you can produce humongous amounts of power. And that is what the Chinese think will make it work there, while in terms of expense and all the engineering risks and ecological risks, etc. However, nobody is convinced that it is only about energy because for downstream countries, for lower riparians like us [India], the Chinese can use their ability to stop this water or release this water, either to create floods or to deny water in times of drought.

There is always suspicion of Chinese dam-making activity because they have done this with the Mekong system. Because of all the rivers that come out of the Tibetan plateau, the Mekong is the other significant one, which India is not concerned with, but many other countries are: Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam. All of them have suffered because the Chinese have built about 11 dams on the Mekong system, and a lot of that has led to unseasonal floods and droughts in all the downstream countries.

Now, India is concerned that the Chinese could divert this water. It will be tough to do so because of the gradient. The water has already come so low by the time they are producing power. For it to reach any place where the Chinese have a population and this water may be required, it would be costly. Power can transmit easily on overhead grades, but for water, you have to deal with gravity. So, if they want to take this water back to a populated area, they might end up spending more power just to lift this water.

So, maybe it will not be so possible to take this water backwards into China, but it will definitely give them the power to regulate this water.

How dangerous is it going to be for India? First of all, it is a great irritant, also because India and China do not really have a water-sharing treaty. They have some basic agreements. One agreement was signed in 2002, last renewed in 2018. That was mostly about sharing data on water flow in Himalayan rivers coming in from the Tibetan side.

The initial MOU on supplies waters was signed in 2004 and revised in 2018, but after that, both sides have shown more urgency, and some cooperation took place until a few years ago, until these tensions arose. After the massive flooding because of the bursting of a glacial lake formed on the Chinese side, about which India did not know, tensions increased. However, since the trouble in Galwan in 2020, the Chinese have not been sharing this data very much. Although there was a meeting held, an expert-level mechanism meeting, via video conferencing in June 2023.

If you see the Chinese readout on the latest visit by our national security adviser to meet his Chinese counterpart, that’s an ongoing special representatives meeting process. In the Chinese readout, they mentioned that the two sides discussed the need to engage on water management of shared rivers. Once again, the trust level with the Chinese is still quite low.

Now, before I let you go, I just have to speak for a minute about the Brahmaputra system in India. Look at the Brahmaputra river as it flows through India. You see it coming from Siang, from Tibet. It comes in. It’s not such a big river. At that point, most of the water in the river is glacial.

So, that comes in, it comes in through the watershed, through the gorges, through the valley. Then these two big Indian tributaries join it, Lohit and Dibang. It becomes a much bigger river. This is where that first, the easternmost Brahmaputra bridge has been built. It’s not really on the Brahmaputra; it’s on the Lohit River. That is the Dhola–Sadiya bridge that’s named after Bhupen Hazarika. That goes over the Lohit River.

As the river enters the plains, you can see it expands. It doesn’t have that much depth to go, and it has a very slow flow because the gradient is so little. That’s the reason it spreads out, and becomes braided as it goes along.

However, India is not dependent mostly on water that comes from the Chinese side because very little water in the Brahmaputra system comes from over the watershed, from the Chinese side. The Siang does (that is, the Yarlung Tsangpo does), but most of the other tributaries, Brahmaputra has 33 tributaries in India—20 on the northern side, 13 on its southern side.

Most of those come out of the Patkai hills, and all of the ones on the northern side come from the Himalayas. They are mostly from the Himalayan snow melt, and also from monsoon water because this area, this part of India, gets very heavy monsoons, beginning, in fact, sometime towards the end of April.

So, these rivers are going to have a lot of water, generally speaking. So, there is no need for us to get paranoid and start losing sleep. However, what the Chinese are doing, one, is provocative. Second, because of the low level of trust that China enjoys among its neighbours, there is always concern about what the Chinese would do. And third, this is now going to give India a sense of urgency in doing something with the water that’s coming into its own territory, particularly, say, with the Siang river or the Brahmaputra, as it’s called as it enters India because that’s where the gradient is available.

There are similar projects planned on Dibang, on Kameng river. Kameng is one of the major tributaries, sort of more on the western side of Arunachal Pradesh, washing into the Brahmaputra. So, those projects, I suspect, will get a sense of urgency.

Also Read: Images show China may be using a secret tunnel to divert Brahmaputra water into desert