Kannur-Muzaffarpur: The soldiers who crossed the border, the fighter pilot in his MiG-21, the paramilitary personnel killed in Pulwama or even the IPS officer gunned down by terrorists in the heart of Mumbai — all of them have become abiding themes of these bitterly-fought Lok Sabha elections.

National security is front and centre of the re-election campaign of the Narendra Modi government like it has never been in any election in the history of India.

At the heart of the narrative is the jawan, who is also tasked with ensuring that the world’s largest democratic exercise, spread over seven phases and 38 days, is free and fair.

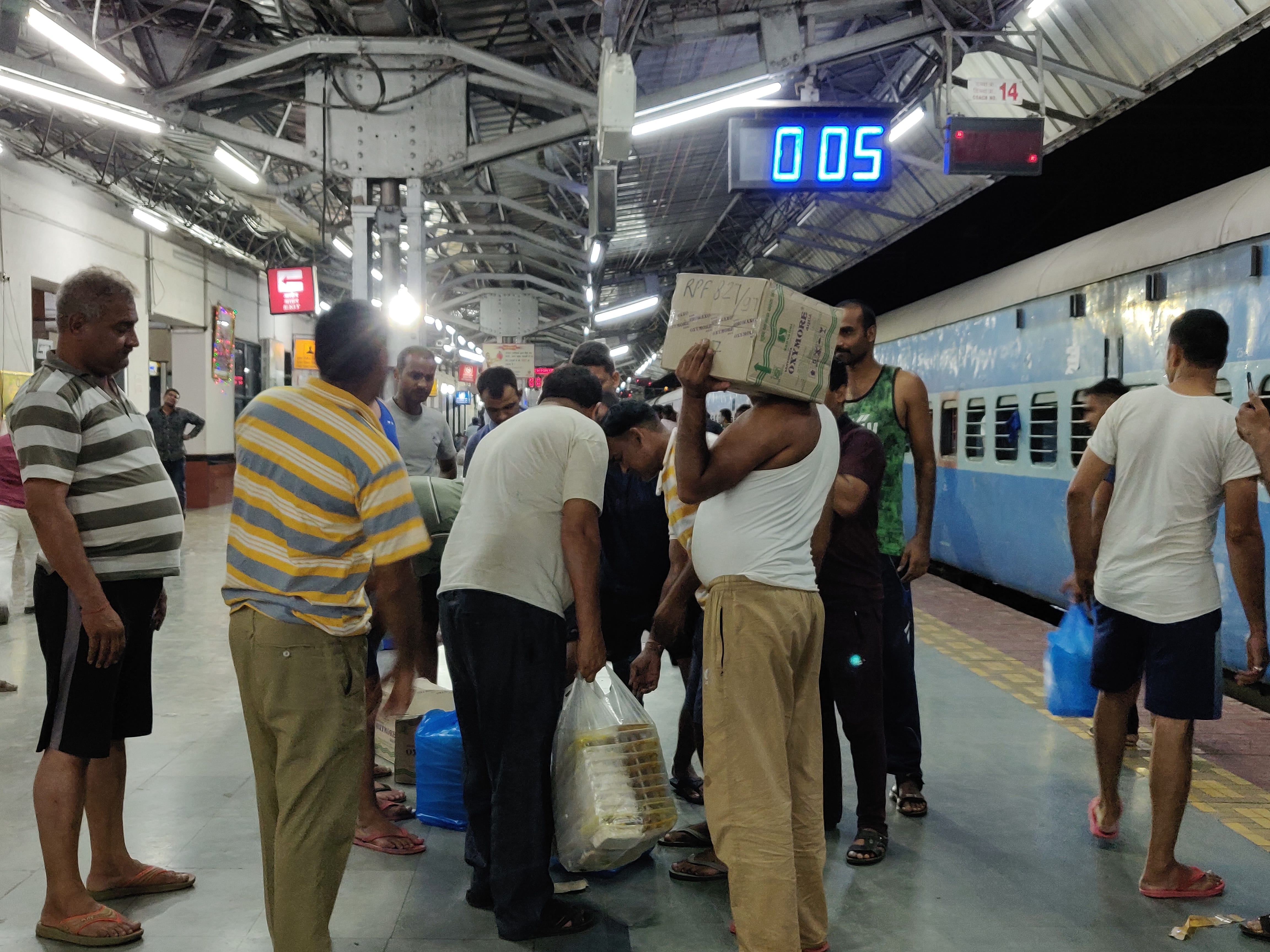

To achieve that, thousands of paramilitary personnel are moved across the country in each phase of the election — from Tamil Nadu to Gujarat, Karnataka to Uttar Pradesh and Kerala to Bihar, among others.

The harrowing experience of their journeys crisscrossing the country is a little-known and untold story of what an ordinary paramilitary soldier goes through to protect the Indian democratic process.

ThePrint accompanied one such contingent of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and Railway Protection Force (RPF) from Kannur in Kerala to Muzaffarpur in Bihar — a four-day journey by train over 2,500 km through six states — to record an effort no election campaign rhetoric can even imagine, let alone address.

Also read: Pulwama makes it to election speeches, but CRPF & its problems are left out

Trouble at the top

Sitting in his uniform, embellished with a series of medals, Rajesh Dogra, 46, deputy commandant, CRPF, juggles three phones and a dozen work-related papers.

On the one hand, he is taking calls and posting updates while on the other, he is restlessly scribbling logs in his file.

The CRPF deputy commandant is the officer in charge of Special Election Train 729, ferrying 977 CRPF and Railway Protection Force RPF personnel from Kannur in north Kerala to Bihar’s Muzaffarpur, a distance of nearly 2,500 km.

The men are on election duty and have to ensure security during the last three phases of the seven-phase Lok Sabha polls.

Dogra’s mind, however, is pre-occupied. And half an hour into the journey, it becomes clear why. He receives a video call on his smartphone — it is his 10-year-old daughter, lying on a hospital bed, her face covered with an oxygen mask.

Dogra pushes aside all his papers to speak to her. She has suffered a lung infection and has been admitted to a hospital in Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, where Dogra has been posted for the past two years.

As he speaks to his daughter, his other phone constantly rings. The CRPF headquarters in Delhi, where a control room has been set up to monitor the movement of these special trains, needs a detailed update on Train 729.

Dogra tries to ignore that call but he soon gives in. With a heavy sigh, he immediately hangs up on his daughter promising to call her back and picks up the other phone.

“All the jawans have boarded. The baggage and weapons were loaded on time. The next stop is dinner at Mangalore Junction. Everything in control,” he updates the control room.

Just metres away in the next bogie, the jawans have settled down. They have eased out of their uniform and boots and have started singing their favourite song — Musafir hun yaaron, na ghar hai na thikana, humein chalte jana hai from the movie Parichay.

It’s a song that lifts their spirits, every now and then, over the next three nights.

Seat number 73 vs a sleeper coach

Constable Nagendrappa of the 105 RAF battalion is elated. In his 23 years of service, the constable says he has never travelled in a sleeper class bogie before.

The central forces are allotted special trains during an election period but for the most part, the trains usually have only general compartments, leaving the soldiers to spend much of their journeys, which usually last three to four days, sitting or standing.

Special Election Train 729, however, consists of only sleeper coaches — providing much-needed respite for the men who have just completed election duty in Kerala.

For Nagendrappa, “this is luxury”.

“There is never enough space or, in fact, any leg room. We are over 92 people travelling in a bogie that can accommodate only 72. And then we have a lot of baggage,” he says. “Where is the space to lie down? There is no space to even sit.”

Nagendrappa belongs to Karnataka. He began his election duty at Ahmedabad in Gujarat before he made his way down to Kerala. That 1,550-km journey, he says, was in a general compartment along with 92 other personnel and 4,000 kg of baggage, which includes luggage, weapons, ration, cooking equipment and bedding.

Another constable, who has been in the force for the past 37 years and belongs to Rajasthan, says, “Fauji ke liye 73 number seat reserved hoti hai (Seat number 73 is always reserved for a soldier). That is an internal joke.”

Seat number 73 is a misnomer, it does not exist; the general compartment of a train bogie consists of only 72 seats.

For the soldiers, however, seat number 73 refers to the space outside the toilets.

The jawan from Rajasthan explains. “When we go back home, we are usually granted leave just days before we have to leave. This way, our reservations are never confirmed,” he says. “We end up travelling on the space outside the toilet. That is seat number 73.”

The constable refuses to divulge his name fearing that he would meet the fate of Tej Bahadur, the BSF constable who was dismissed from the force after posting a video complaining about the quality of food. Tej Bahadur was backed by the SP-BSP alliance after he filed his nomination against Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the Varanasi Lok Sabha constituency but his election papers have since been rejected.

The Rajasthan constable says that even in normal deployment, the soldiers are allotted a general compartment, in which 92 to 100 of them are expected to travel.

“We lay our baggage on the passage and sit on them as there are not enough seats. Even then, 20-25 people have to be on door duty as there is no space left to even stand between seats,” he says. “This is how we have been travelling for so many years.”

Also read: No takers for women’s quota in CRPF, CISF or BSF as forces strive to fulfil Modi govt plan

Food, or the lack of it

It is 8 am on day two and Dogra is infuriated. Only 500 breakfast packets were delivered at Madgaon in Goa at around 3 am; one-half of the soldiers will now have to go hungry.

As he picks up his phone and gives the caterer an earful, there is no end to his troubles —the call is interrupted by a soldier with an even more grim update. “Sir, there is no water in the train and the food in the lunch packets is spoilt,” the soldier says.

Vexed, Dogra immediately hangs up on the food deliverer, picks up his other phone and starts making calls, this time to his senior officers.

The train is to cover the distance of 2,500 km in four days and three nights but on its second day of the journey it has run out of water.

With the temperature hovering over 42°C, the toilets lying filthy and the lunch packets emitting a fetid smell, there is a putrid air in the compartments.

“Throw them (breakfast food packets) away,” says deputy commandant (operations) Nitish Rampal. “See if someone has some fruits.”

The food is delivered by the Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation (IRCTC). The CRPF, the nodal agency for coordinating the movement of all Central Armed Police Forces, has tied up with the IRCTC to ensure that the jawans on board the special trains get their meals on time.

Each special train has designated stops to pick up breakfast, lunch and dinner packets and for watering and cleaning of the train.

But much like this one, most of them usually run late, leading to a logistical nightmare down the chain. For instance, when the trains run late, the food ends up not getting collected on time, leading to it being spoilt and the jawans going hungry.

The timing of the collection is also at odd hours.

Sample this: On day one of the journey, breakfast was collected at 3:20 am at Madgaon in Goa, lunch at 10 am in Maharashtra’s Ratnagiri.

By the time the soldiers were ready to eat their breakfast at around 8 am, it was spoilt, so they then waited and ended up having their lunch packets that arrived at 10 am.

For dinner, the train was to reach Nashik Road station at 9.40 pm but it only reached the station at 12 am, over 2 hours late.

By the time it was distributed, it was way past midnight — leaving the soldiers without food for nearly 12 hours.

“It is still a great initiative by the government and solves a lot of our problems,” says train commander Dogra says. “This collaboration with IRCTC was done so that the jawans do not have to cook their meals while on the way for duties.”

Constable Panduranga agrees. “Earlier, the train used to stop at a deserted station and everyone got down to set up a mess on the platform. We would place bricks and wood to make a fire and cook our own food, mostly khichdi,” says Panduranga, also from Karnataka. “Once the companies were fed, we would wrap up our vessels to get inside the train again. This used to repeat at least twice a day.”

If there wasn’t sufficient time, says constable D. Dilip, personnel would fan out every time a train stopped to search for food.

“We used to form two search parties and ask them to hunt for food within a one-kilometre radius in all directions and fetch whatever they could lay their hands on,” says Dilip from Andhra Pradesh. “That might include biscuits, namkeen and sometimes even poultry. This way, we would stock up for our travel.

“After this exercise, the train commandant would blow a bugle and ask everyone to assemble. We would then get inside the train,” he says. “Sometimes, we would wrap up even before the khichdi is properly cooked; so, we used to keep it in the compartment and put our luggage on top of the vessels so that they get enough steam to cook and the food is at least edible.”

Election day and training

It’s day three of the journey and with the taps having run dry, the jawans are waiting for the next “proper railway station” so that they get at least sufficient water to wash their faces.

They are at least a day from their destination and the men say that the journey doesn’t really compare to the election task ahead.

“For us this travel, no matter how hectic, is rest time,” says CRPF inspector Veomesh Shanshul. “Our real work starts after this.”

Once the jawans reach their designated election deployment locations, they are on continuous duty, which includes overnight guarding of the Electronic Voting Machines (EVM), area domination, patrolling and poll booth guarding.

“We walk for 25 km a day, work for over 36 hours continuously,” says Shanshul, who is from Uttarakhand. “What gives us a boost is our uniform. Once we wear that and go to the ground, people are assured that nothing will go wrong. This faith in us is what keeps us going. We then forget about these minor inconveniences.”

Most on board the train are veterans of the election process and for some, this is the last.

A Sikh constable is set to retire next year. He is the chief raconteur here, sharing experiences and stories with those just starting out. According to him, West Bengal, Bihar and MP are the toughest states when it comes to securing elections.

“There have been episodes of attempted booth capturing in Bihar,” he says. “There are people from specific parties who sit outside the booths and try to influence voters. They also create a ruckus when they feel their voters are not coming.

“In states such as Bihar and UP, these trouble-makers station themselves 100m from the booth and threaten voters on their way to vote,” he tells some of those listening to him. “We should make sure that we patrol this area so that it does not happen.”

The central forces undergo two weeks of training before they head out for election duty and are given specific instructions for specific states.

The deployment strength is dependent on the sensitivity of the booth.

The central forces reach a state at least three to four days before it goes to the polls and begin area domination exercises that include frequent patrolling.

“Once we are deployed, we entertain no one from the state authorities. We do not talk to anyone or give out a signal that we can be talked into anything,” Nitish says. “We do not take even a single drop of water from the state police there. Our task is to get elections done and that is what we concentrate on.”

A day before polling, the EVMs are placed inside the booths and the soldiers take their positions.

On the poll eve, the EVMs are guarded by a minimum of four personnel and are headed by either a head constable or an assistant commander. All the jawans get are two hours to rest that night before they are back at poll duty at 6 am the next morning.

On polling day, two soldiers guard the main gate and two are responsible for maintaining the queue and making sure that only one person goes inside a polling booth at a time. The personnel also keep a watch on what is happening inside the polling room though they never step inside unless required.

A strike reserve unit that has at least 10 personnel is always mobile, taking rounds of all polling booths in the districts to ensure that law and order is maintained. It is headed by a company commander who is either an assistant commandant or a deputy commandant-level officer.

Once the polling process is over, one unit heads to the EVM strongroom in the region while rest are back on the road, or in this case the rails.

Also read: Jobs & milk to helping the stranded — how a CRPF helpline became a lifeline for Kashmiris

The last leg

It’s 5 am on day four and the train has stopped at the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya railway station in Uttar Pradesh for watering.

The stop is for an hour to fill the train with water but before that happens, the pipes at the station have been expropriated by the jawans.

They rush from the bogies one after another, armed with towels and soaps, jumping at the first opportunity they get to catch hold of the water pipe. Unperturbed by the onlookers at the station, some even taking their videos, the jawans disrobe, stand on the rail tracks and begin taking a bath.

By 7 am, the jawans, having had their breakfast, have clipped on their medals and secured their boots. The train is expected to reach their destination, Muzaffarpur, by 1 pm.

But much like the rest of the journey, it doesn’t go to plan.

At around 1 pm, the train stops in the middle of nowhere — almost 60 km from the nearest village of Sohanpur in Bihar’s Champaran district.

To make matters worse, there is no mobile network.

Train commander Dogra attempts to contact Northern Railways authorities but his efforts are hampered by the poor network. He assigns four constables, who together have 10 phones between them, to try on different SIM cards but none catch a network.

For the next three hours, Special Election Train 729 does not move an inch — left to bake in the searing heat.

The power supply has stopped and with it, the fans.

It’s all too much for one exasperated jawan, who loses his cool.

“This is inhuman. Is this a way to treat us soldiers?” he asks. “They have abandoned us in a train at a faraway location where there is no signal and we are sitting here without any water or food.”

“I understand if it is an emergency deployment, but for elections, they had five years to plan,” he says. “They definitely could have planned it better. Why put a train for such a long route?”

The last meal the soldiers had was at 7 am and it is now nearly 5 pm. There was no lunch arranged as the train was scheduled to reach Muzaffarpur at 1 pm.

In the sleeper class bogies, the jawans have begun to loosen their shoelaces.

Constable Jaiveer Singh is among those unperturbed. He uses the time to pen an ode to his wife. “Hai hai yeh majboori, yeh fauj ki naukri zaroori. Meri lakhon ki yeh naukri meri madam ko na bhaye (Sigh, the compulsion of this duty, this job that displeases my wife),” he sings to the tune of the famous song from the 1974 blockbuster Roti, Kapda Aur Makaan.

Constable Rajesh Kumar Dubey, a yoga expert, has got everyone taking deep breaths.

As he goes through his yoga asanas, the train begins to roll, sparking wild cheers across the bogies.

The happiness, however, lasts only for an hour. This time the train has halted at Turki, just 20 km from Muzaffarpur. Thankfully, there is a hand pump in the area.

Everyone gets down and rushes to the lone hand pump — they fill their water bottles, wash their faces.

“It is wastage of human resource, money and time. They can ferry us to our designated duties in half the price in a plane and for our equipment and baggage, they can use a BSF chopper,” a frustrated jawan says. “But no, they have thrown us in the train for four days. It is also not that we will get any rest after getting to our destination.”

His colleague calms him down, “Don’t forget it is our duty. This is for our nation. No point getting worked up. Go wash your face,” he tells him.

More join in at the hand pump, and the soldiers fall prey to a social media phenomenon — they take a group selfie.

‘Raat abhi baki hai‘

It is 8 pm and the train has finally reached Muzaffarpur. It is eight hours late but the journey is far from over.

The jawans have not had anything to eat since 7 am in the morning and it will take at least six hours before they settle down at their respective locations.

“We are now heading to Hajipur, which is two hours away from here,” says constable Somnath. “The civic authorities have arranged for some room in a school. After we reach there, we will clean the rooms and then set up a mess to cook food.”

“It will be 1 am by the time the food is cooked and we all eat. And tomorrow, the day starts at 6 am,” he says loading his luggage in the carrier. “Raat abhi baki hai (There is still the night to go),” he smiles.

Nice article madam seriously…hope the Central Govt. provides better facilities for our jawans atleast after reading this…

It’s really written from ground. I am also in same condition from last 2 and half month. Best part we seen south to north in this journey and few of us not availed our leave from last 6 to 7 months. But still we found many thing to enjoy our self.

We also faced same thing in 5 state elections in last last 2 months.

Outstanding coverage.

It is a results of total lack of logistic planning. Why couldn’t they plan shorter troop movements? If they had planned polling in southern stares on different dates instead of on a single date troops could have moved from Kerala to Karnataka or TN to Andhra/ Telangana. Similarly Rajasthan to Gujarat, MP to Maharashtra, Odisha to Bihar/ Jharkhand, Andhra to Chattisgarh etc. where travel is only to neighbouring state and journey is for not more than 8 hours.

Why should a contingent move from Kannur to Muzaffarnagar? That’s the most arduous and long journey that they could have to possibly endure. The EC has to make use of better planning and have a more humane approach to election duty staff and security agencies.

Very honestly covered and brought out all the issues being faced by unsung heroes of CAPF .This is only one example of the plight of CAPF jawans those are not recognised by the government , media and country men too. Thanks a lot for covering the whole movement and narrating well. Hope other reporters will also do their job . Thanks once again . Jai hind.

honestly a great story. i wish media would show things like this instead of focussing on our stupid politicians. is this the way to treat our brave jawans. good story

A well written piece. The reality stares from the ground. A pointer to the worst planning. Joining an elite space club is of no use if we cannot plan a train journey of four days and less than 1000 people.

Picture abhi bahut baki hai Maam…Abhi to bas ye shuruaat hai….pls write something about election day and after that…

Great Article. This clearly shows poor planning on part of higher officials who are certainly illiterate. Why not use IAF carrier for these jawans, certainly saves lots of time and energy. Politicians have so much wealth should also mobilise them for well being of our jawans !!!

This is great stuff. Well written. Such insights are very uncommon in main stream media. Kudos ThePrint team.

Now that this article has come describing vividly, the travail of the travel of the jawans, if Modi gets re-elected, it’ll be set right.

It’s eye opener,well written also.

Need better planning.

Salute to our military personnel.

Really heart-rending.. but what’s the connection with Modi? Mischievous title! It’s really sad that they go through so much discomfort. Even more painful that despite this, many don’t vote! God help our country

Well written article and the absolute truth. All who have performed election duty or being a train commander (like myself) can fully relate with this. And all this huge wastage because the so called leaders of police have messed up the State Police and made a mockery of them so much that they cannot be trusted. Yet such abject incompetence gets rewarded; whilst in comparison CAPF personnel get ‘rewarded’ in form of buggery for their competence.

This is very pathetic. The country which has fastest growing economy certainly can do better for these jawans. First of all whether it is really required to make such long distance arrangements. The security staff nearby centres can be deployed. If at all required, our country can definitely afford the cost of airlifting these soldiers. After all only because of such dedicated soldiers, we can proudly be a largest democracy in world.

a very well written article …an eye opener. Wish authorities read and make policies accordingly . Its easy to make plans sitting within comforts of ac offices and entirely a different perspective if you travel with the soldiers . Hats off to our officers and jawans who keep the wheels of the democracy rolling ….f nothing else at least their journey can be made a little easier.Even the railways can have some tatkal scheme for the jawans. Kudos to Ananya for taking up this journey to see the grit and determination of our soldiers from close quarters. Keep up the good work.

All the tall talk of fastest growing economy and such crap cannot hide the fact that we are a primitive country, almost always administered incompetently by pathetic morons.

The ‘headline’ is misleading, if not downright ‘mischievous’. Why drag “Modi” into this narrative of the tribulations and toils of the forces securing this election? It is such obsession ( a la Mamata, RG, Kejri et al ) with Modi that makes writers like this one ‘avoidable’ Why write when you turn off your readers with your ‘personal’ bias impinging on the content?

An exhaustive articles on the harrowing routine the CRPF jawans undergo during election duties. Our politicians need some insight into these problems and they should make better planning for the journey of soldiers. There should be a rule. All the politicians while filing their nomination should produce a certificate for having served in CRPF for at least one year. This certificate should be made compulsory for all those who stand for election. Then only our politicians will learn.