Ahmedabad: Gujarat has previously been lauded for its effective healthcare system, which has managed to fight serious disease outbreaks like swine flu, ebola and the Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. That’s why it has come as a shock that in the Covid-19 pandemic, the state has registered the highest mortality rate in India — 4.38 per cent — which is considerably higher than the national average of 2.49 per cent.

The total number of infections in the state now stands at 51,399, and on 20 July, it registered its highest single-day spike of 1,026 cases.

In the initial weeks of the outbreak, government hospitals in Gujarat, especially Ahmedabad Civil Hospital, had grabbed headlines for their high mortality rates. The Gujarat High Court had slammed the state government, saying the conditions at the Civil Hospital were “pathetic”, and that the hospital was “as good as a dungeon, may be even worse”.

In June, the state had a very high mortality rate of 6.2 per cent, which was of great concern as it was more than double the national average of 2.8 per cent. But it managed to reduce it down to 4.38 per cent, though still the highest in the country.

Then, on 21 July, the single-day number of deaths peaked again at 34, having not crossed 20 since 4 July.

So why is Gujarat is struggling with mortality in the face of the pandemic?

Also read: Ahmedabad Civil Hospital a ‘dungeon’, will speak to doctors directly: Gujarat HC

Late identification

Data from the health secretary’s office indicates that patients are seeking treatment in hospitals pretty late. The average span of hospitalisation among discharged patients in Gujarat is 11.03 days, while among the deceased, it’s 6.24 days.

Doctors say late identification is one of the prime reasons behind Gujarat’s high mortality rate. During the initial phase of the outbreak, the patients were admitted into hospitals for Covid-19 at a late stage, which made their symptoms more aggressive, leading to an increase in fatality rate.

Dr Chandresh Jardosh, president of the Indian Medical Association in Gujarat told ThePrint: “Patients are coming very late for treatment. We prescribe treatment to them and advise them to go get tested. But they self-medicate and end up coming here late, which increases the chances of fatality.”

Late identification also increases the viral load of the patient, making the case more fatal.

Doctors also said patients associated the hospitals with high mortality rates, and were not seeking treatment from them.

Dr Mona Desai, president, Ahmedabad Medical Association, said: “Awareness among people wasn’t a problem. Since the mortality rate in hospitals was high, patients were afraid to go to these hospitals.”

This counterintuitive approach resulted in increasing the mortality rate, she said.

Comorbidities

Over 83.2 per cent of deceased patients in Gujarat had comorbidities, well above the national average of 57 per cent (as on 2 July), according to a government analysis of deaths conducted by the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme under Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Dr M.M. Prabhakaran, officer on special duty at Ahmedabad Civil hospital, said: “Gujarat is rich in diseases like diabetes. It is the most common co-morbidity.”

In addition, more than half of the deceased Covid-19 patients (56.4 per cent) belonged to a high-risk age group of more than 60 years. This meant that over 40 per cent of patients who died were in the low-risk age group, unlike the rest of India.

According to the government analysis, the age-wise break up of deaths was 39.02 per cent in the 60-to-74 age group, and 12.88 per cent in patients above 75.

Also read: Make Covid treatment affordable or lose licence: Gujarat High Court warns hospitals

Congestion, panic and hiccups in guidelines

Dr Dileep Mavlankar, director, Indian Institute of Public Health, talked about how the initial congested hotspots in Ahmedabad contributed to the high mortality rate.

“The initial epidemic in Gujarat started in congested areas of central Ahmedabad like Jamalpur, Shahpur etc.,” he said. “The first few cases saw a very big viral load since these are congested areas; that’s why initial mortality was very high.”

Mavlankar said there was a lot of “panic” owing to the lockdown, and that people were scared of going to public hospitals.

Imran Khedawala, MLA from Jamalpur-Khadia in Ahmedabad, one the biggest hotspots in the city and someone who contracted the virus too, gave insight into the confusion and fear.

“At the time, all the chemist shops and local clinics were also forced shut. So, people couldn’t receive treatment for diseases other than Covid-19. This, too, contributed to the death toll,” Khedawala said.

“People didn’t trust government facilities and hospitals. They were so scared that when doctors approached them in their homes, people shut the doors on them,” he explained.

Khedawala said the situation in his constituency is more or less contained now. Jamalpur is now registering about 20 times less cases than it was at the peak of the infection in June.

Some doctors at government hospitals also said there was confusion about the guidelines given by the government on how Covid patients must be admitted. Dr Rakesh Joshi, additional medical superintendent at Ahmedabad Civil Hospital told ThePrint: “First, there were guidelines on how anyone with symptoms must be admitted into the hospital, which overburdened our facilities. Then, the guidelines told us that only patients who test positive must be hospitalised.

“Now, the final recommendation is that only those patients who test positive and have severe symptoms must be hospitalised. This has taken some load off the Covid facilities.”

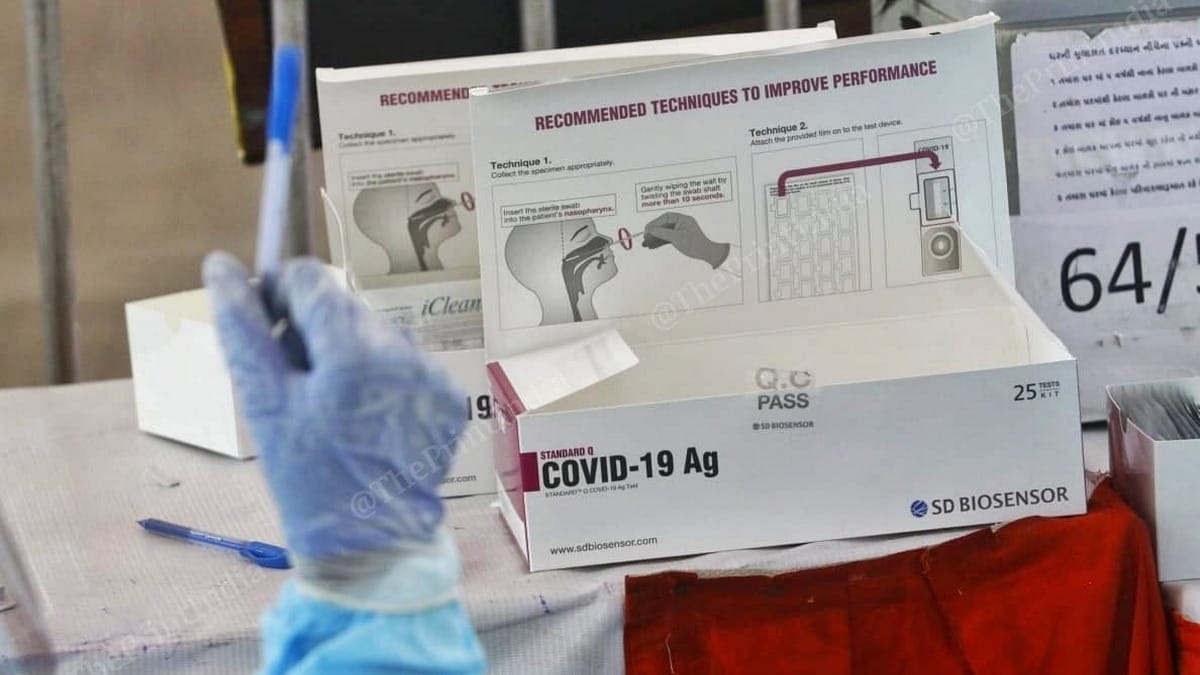

Not enough testing

Dr Jardosh, who spoke about the late identification of cases, also attributed the trend to low-testing, while Dr Desai’s Ahmedabad Medical Association filed a plea in the Gujarat High Court that the tests be made proportionate to the population.

Desai told ThePrint: “In other states, over 25,000 to 30,000 tests are being conducted, even in Delhi, whose population is less than Gujarat’s. Similarly Tamil Nadu, which has almost the same population as Gujarat, is conducting 30,000 tests.”

But the figure for Gujarat on 20 and 21 July was 12,867 and 13,693 respectively.

Desai said the “biggest problem right now” was that the state was not allowing asymptomatic patients to be tested.

Asked whether Gujarat needed to ramp up testing, Jayanti Ravi, principal secretary, health, told ThePrint: “We have been progressively ramping up testing. We have a large number of labs right now. Further, if you look at tests per million, we are far more than the national average.”

However, the national average of tests per million is 10,486, while Gujarat has recorded 8,809 tests per million.

In a bid to ramp up testing, the Narendra Modi government had sent a letter to states and Union Territories on 1 July, advising them to do away with the mandatory requirement of a prescription from a government doctor. It had pulled up some states for not conducting contact-tracing properly. Gujarat’s “restrictive testing” was among the reasons behind the letter.

A senior Union health ministry official said: “The state made testing very restrictive at one point. They made it mandatory for a government doctor to sign. That is why a letter went out from the government of India asking states to remove such restrictions.”

Also read: Gujarat doubles daily Covid tests as alarm bells ring after central govt team visit

‘Different strain of virus’

Asked about claims that Gujarat’s viral load was high, principal secretary Ravi told ThePrint: “It is still a hypothesis but the strain of the virus in Gujarat was different from the one found in many other parts of the country. Internationally, there were two strains, one that came from Italy and another from Iran.

“This is yet to be established by studies, but there is an ‘L’ strain and an ‘S’ strain. The ‘S’ strain is less virulent and the ‘L’ strain is more difficult to recover from. Experts seemed to be of the opinion that the virus in Gujarat appeared to be from the ‘L’ strain.”

However, ICMR’s head of epidemiology and communicable diseases, Dr Raman R. Gangakhedkar, who has since retired had said: “It will take some time for us to know the predominant quasi-species of the novel coronavirus in the country. But mutations are not likely to make potential vaccines ineffective, as all sub-types of the virus have the same enzymes. Also, it has been in India for three months and it does not mutate very fast.”

How did mortality rate fall since June?

Experts believe that an “attenuation”, or weakening, of the virus might be at play.

Dr Mavlankar said: “The mortality rate has gone down, even though cases have increased. They are mild cases; they don’t have the same severity as April.

“Central Ahmedabad has developed some kind of immunity and infections have gone down. But now, the disease has spread to other parts of Ahmedabad.”

The infection is taking a “milder shape” in these areas, since they are not as congested as central Ahmedabad, and have “richer people who may have better immunity”, he said.

“The virus also mutates. There is some attenuation which means that the virus has become less virulent. This type of pandemic is a basket of fireworks; wherever the first match is struck it starts burning. Ahmedabad was the first to burn and the pandemic will end there. Soon, it will be in Surat and Vadodara — this is called flattening of the curve,” Mavlankar explained.

Jayanti Ravi, principal secretary, health, also cited “attenuation” to explain these milder cases.

“Some experts suggest attenuation. As the virus cycle affects people and goes through different cycles of human transmission, attenuation occurs and the virulence gets slowly reduced,” she said. “The patients that are coming now are not as critically ill as the ones before.”

Asked whether Gujarat was expecting a peak soon, she said: “It is not like the entire state has a single trajectory. In Ahmedabad, we are seeing that there is hopefully a reversal of the peak.

“We seem to be much clearer on how to deal with the virus now. If we continue to ruthlessly surveil, use ‘Dhanvantri Rath’ (a mobile van providing non-Covid essential healthcare services to people’s doorsteps), contain hotspots, ensure people get tested, we can contain the virus,” she said.

Also read: Indian news channels line up outside hospitals in opposition-ruled states, skip BJP’s Gujarat