New Delhi: In 2016, when 41-year-old Divya Prakash Dubey wrote his novel Musafir Cafe, he had no idea that it would inspire a cafe revolution across the country. At least a dozen cafes opened with the same name. Eight years on, the popularity of Dubey’s book hasn’t waned, and he still receives daily messages from readers.

“I read your book Musafir Cafe; it was so amazing. I loved it. Thank you for writing it,” said one such message as Dubey scrolled through Instagram on a Tuesday afternoon.

Dubey enjoys star-like status among Hindi fiction readers. He is the Chetan Bhagat of the Hindi book world, and then some more. He is the toast of lit-fests where he often talks about how he chose engineering like every other Indian youth.

“Before becoming a writer, I did what everyone tries to do in our country—B.Tech,” he said at the popular Sahitya AajTak lit fest last November, drawing laughter from the audience.

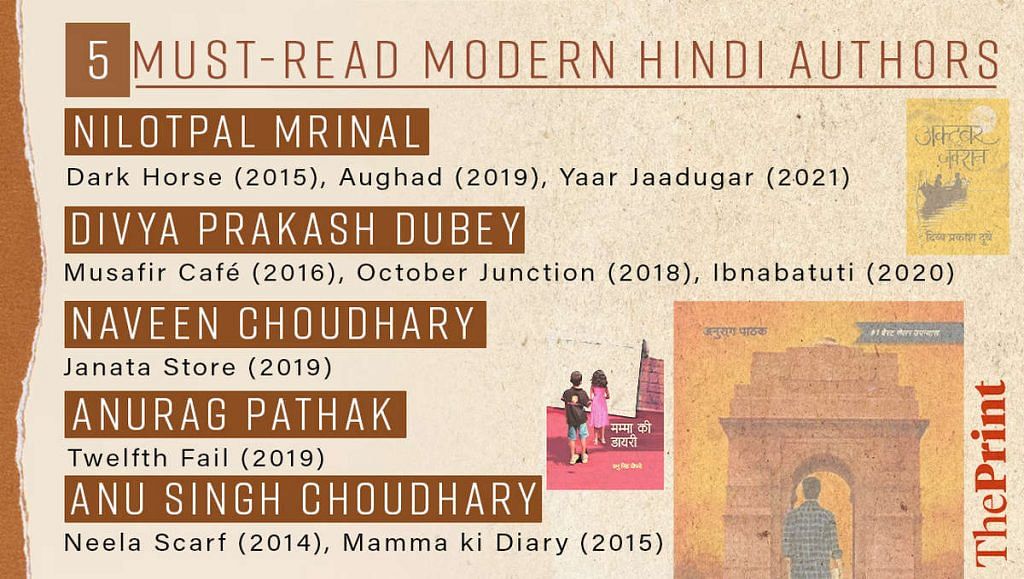

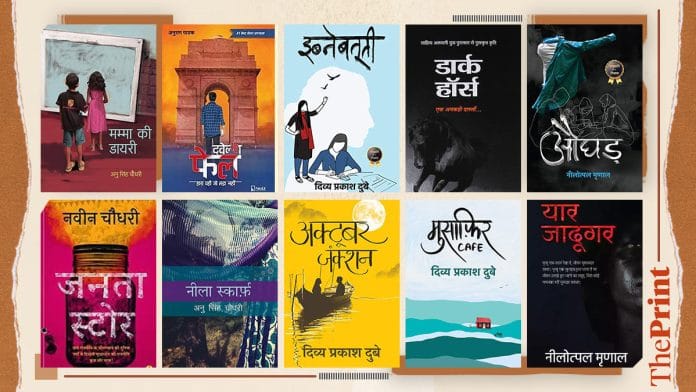

Dubey gets top-billing in the contemporary Hindi fiction landscape. But there are others as well. At a time when readers are declining and content is devoured online, writers like Nilotpal Mrinal, Anu Singh Choudhary, Satya Vyas, Naveen Chaudhary, and Vivek Kumar are fighting the odds successfully. Romance, mythology, science fiction, and inspiring stories about aspiration—these are the genres that sell.

On this front, Hindi fiction often mirrors the trends in English novels.

“Whatever is trending in English, the same is trending in Hindi. People are reading about dreams, travel, romance, and suspense. Detective fiction is not that popular these days,” said Shailesh Bharatwasi, director of Hind Yugm, a Hindi publishing house.

Nilotpal Mrinal’s Dark Horse and Anurag Pathak’s Twelfth Fail, for instance, delve into the world of IAS dreams and aspirations. Then there is Dubey’s Musafir Cafe, which explores modern love through the story of two career-oriented people who meet at their parents’ behest. In this novel, Sudha, a jaded divorce lawyer, and Chander, a software engineer, bond over their scepticism about marriage, eventually living together and falling in love—until things fall apart.

I used to tell my stories to my office colleagues like Satyanarayan ki Katha. I used to write on weekends, and Monday used to be the day when everyone listened to my stories

-Divya Prakash Dubey, author

Musafir Cafe has garnered a cult following among Hindi readers. People frequently quote from it in conversation and share excerpts in their WhatsApp statuses and Instagram stories.

Dubey recalled a waiter approaching him while he was having lunch at the cafe in Mumbai’s Prithvi Theatre, claiming to know a writer with the same name.

“The waiter said that he has never seen the writer, but his name is the same as mine,” said Dubey, smiling ear to ear. “At that moment, I realised that my writing has done its job.”

Also Read: Harry Potter sealed the defeat of Hindi books for children. But a new ‘pitara’ looks promising

Hindi storytelling 2.0

With visual media and browsing culture taking over consumption habits, new writers are writing for a new generation. They’re accessible on social media, interacting with their readers constantly and not locked away in ivory towers. They are now part of the hustle culture of self-promotion.

But this shift may come at a price—a possible decline in the depth and impact of stories. Rama Shankar Kushwaha, an associate professor of Hindi at Dyal Singh College in Delhi University recalls a time when Hindi fiction “comfortably” tackled rural issues, corruption, and other serious topics.

“Be it Shrilal Shukla’s Raag Darbari or Maila Aanchal by Phanishwar Nath Renu–we used to see themes like corruption in novels. But that is missing now,” he said.

Published in 1968, Raag Darbari is a sharp satire set in a post-independent rural India. It depicts how politics becomes a stepping stone to power, involving everyone from farmers to college students.

“Since Raag Darbari, no novel has created such a stir,” declared Kushwaha.

But the India of Raag Darbari no longer exists. Today, it’s about aspirations, start-ups, Instagram reels, and influencers. And writers are catering to this consumer base. They have fan bases on social media, get invited to prestigious lit-fests like the Jaipur Literature Festival, Sahitya AajTak, and Rekhta. Now, they are writing for Bollywood, OTT platforms, and even organising storytelling shows. And against all odds, they’ve succeeded.

Many well-known writers started out in other professions. Writing was a passion that kept them up at night. Divya Prakash Dubey, for example, studied engineering and earned an MBA before working with a private company.

“I used to tell my stories to my office colleagues like Satyanarayan ki Katha. I used to write on weekends, and Monday used to be the day when everyone listened to my stories,” said Dubey.

Today, Dubey’s books are available not just in India but in public libraries in the United States. As his fame spread, he even received marriage proposals.

“One time I received an appreciation letter from America. The person talked about my book but later asked about my gotra. He was Brahmin and wanted me to get married to his daughter,” said Dubey.

And then the time came when Dubey realised that he could sustain himself by writing. He left his ‘regular’ job in 2020.

“I got so much work that I was not able to manage it. There were audiobook series, cinema work. Now, another market has opened up—people are paying to attend standup comedy and storytelling shows,” said Dubey.

Writers turned social media users into readers. One user comes to read one writer, but ends up exploring the work of a second one, and then a third one.

-Anu Singh Choudhary, novelist & screenwriter

Similarly, actor Manav Kaul, who has written about 10 Hindi novels, sees himself as a writer more than a performer.

“I am 98 percent a writer and 2 percent anything else,” said Kaul in an interview. Whenever he engages with his fans, he encourages them to write.

“I was in Lucknow, attending a session by Manav Kaul. He told us to read a lot and start writing whatever you think and feel,” said Manoj Singh, a Delhi University student, who lives in Uttar Pradesh.

But writing doesn’t just mean novels. Established Hindi fiction writers have branched out to writing scripts, screenplays, and dialogues.

Anurag Pathak contributed to the screenplay for the film adaptation of his novel, Twelfth Fail. Dubey wrote the Hindi dialogues for the popular Tamil movie franchise, Ponniyin Selvan. Anu Singh Choudhary, known for her novels Mamma Ki Diary and Neela Scarf, has established herself as a screenwriter as well, having written three seasons of crime thriller series Aarya.

Another popular writer, Satya Vyas, is on his way to becoming a fixture in the OTT world. His novel Chaurasi, set in the backdrop of the anti-Sikh riots, was turned into a web series. Adaptations for the small screen are also underway for three of his other books— Dilli Darbaar, Banaras Talkies, and Baaghi Ballia.

“The positive thing is that there has been innovation in the subjects being written about. This is a time of transition,” said Vijendra Chauhan, associate professor of Hindi literature, Delhi University.

Engineers, bankers, marketers, filmmakers, and corporate managers are making their mark on the writing scene, breaking down traditional barriers of language, subject matter, and self-conscious intellectualism.

More visibility for women

It’s not only male writers who are making inroads into the Hindi fiction universe; women are also experimenting with fresh themes and formats. Bilingual Hindi-English author Anu Singh Choudhary is one such example.

One of her more popular novels, Mamma ki Diary, is an honest and intimate account of being a mother of twins who is trying to make sense of institutions like marriage, the changing nature of relationships, the ebb and flow of ambition and desire, and gender rights. Her first book, Neela Scarf, was a collection of short stories. Her protagonists include a retired Air Force officer, a Dalit woman serving the wealthy, and a homemaker struggling with a lack of purpose.

The traction her work got led to her branching out as a screenwriter. Besides Aarya, she’s written for OTT shows like Scoop and Grahan as well.

“In the 70s-80s, writers like Rahi Masoom Raza and Kamleshwar used to write screenplays. But after that, there was a pause in this. But now writers are exploring and doing good in new mediums,” said Choudhary.

Also Read: Male gaze has met its match. Women writers are rewriting Bollywood, Aarya to Rocky Aur Rani

Aspiration sells

The new tribe of Hindi fiction writers are breaking the stereotype of the reclusive, reticent author. Nilotpal Mrinal, 39, author of Dark Horse, Aughad, and Yaar Jadugar, likes spending time with readers. Small-town aspirations, rural life, and death are the broad themes for all his novels.

He was a UPSC aspirant back in 2014, and a leader in the protests against the revised examination format that year. He’s not forgotten his roots.

“Whenever I come to Delhi, I visit Mukherjee Nagar and meet the aspirants,” Mrinal said.

His most popular book is Dark Horse, which he claims has sold more than one million copies. It vividly portrays the trials and tribulations of UPSC Hindi-medium UPSC aspirants from rural and small-town India as they navigate life in the big city while preparing for the country’s most competitive exam. This novel received the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar in 2015, conferred to young writers for outstanding works in Indian languages.

“I decided to write Dark Horse when I was protesting. The story was relevant to many,” said Mrinal. “I did the marketing. I reached out to people. I told them to post pictures with my book—a bookselfie (selfie with a book).”

When Mrinal is not writing, he sings and uploads his music videos on his YouTube channel, which has 133K subscribers. His songs touch upon themes like student migration from the Hindi heartland states, the disconnect between villages and cities, and the struggles of UPSC aspirants.

Current Hindi writers are writing about love and contemporary experiences. They are unable to find new topics. Classics are missing from new Hindi writing.

-Jaiprakash Pandey, book reviewer

Aspiration is the current buzzword, evident in the success of books like Twelfth Fail (and its Bollywood adaptation) and web series such as Aspirants and its spinoff Sandeep Bhaiya.

“People are living with many broken dreams. Most jobs come with immense pressure. In this struggle, they find pleasure in stories that provide satisfaction,” said Dubey. “With such stories, people fulfil their dreams vicariously.”

Unlike the older generation of Hindi writers like Premchand, Yashpal, and Nirala, today’s authors have to vie with social media and smartphones for attention spans.

Old vs new

In the past, the world of Hindi literature was primarily populated by writers from academia, activism, journalism, or gatekept literary circles. But today, a diverse range of professionals—engineers, bankers, marketers, filmmakers, and corporate managers—are making their mark on the writing scene. These new voices are breaking down traditional barriers of language, subject matter, and self-conscious intellectualism.

Literature changes with the times, and contemporary Hindi novels reflect or react to new realities.

“Trends keep changing. Now writers are writing about topics like depression,” said Bharatwasi from Hind Yugm. This was not the case even 20 years ago. “Acceptance of love has increased in society. Earlier, if a writer wrote about inter-caste marriage, it was supposed to be a big thing.”

Writers have also had to adjust the style of their writing. Unlike the older generation of Hindi writers like Premchand, Yashpal, and Nirala, they have to vie with social media and smartphones for attention spans. The books being written today are less dense, catering to an audience that’s grown accustomed to reels and shorts.

“People have different struggles now. With the internet, life has become hectic, and people don’t have enough time,” Bharatwasi added. “The language of social media has reached the world of fiction.”

However, some critics argue that, unlike their predecessors, contemporary writers are not able to create enduring classics.

“Many past writers have written works that are still relevant in present times, and books like Raag Darbari, Kamayani, and Gaban are still being read,” said Jaiprakash Pandey, who reviews books for AajTak Live. “Current Hindi writers are writing about love and contemporary experiences. They are unable to find new topics. Classics are missing from new Hindi writing.”

The hunger for easy-to-digest yet compelling stories has fuelled a rise in short fiction. Platforms like Pratilipi—an online self-publishing portal—provide a space for new writers and attract many readers.

There is also an audience for oral fiction, with author Neelesh Misra’s storytelling radio show Yaadon ka Idiot Box running for nearly a decade from 2011. The raconteur’s stories even spawned a book series.

Previously, writers used to seek validation from literary magazines such as Hans, Saraswati, and Indu. But with social media and self-publishing opportunities, writers look to their fans for validation.

However, critics and publishers like Shailesh Bharatwasi and Jaiprakash Pandey express worry about the diminishing sense of community among authors.

“Earlier, when magazines used to be there, writers had this feeling of community. But we don’t see it anymore. In novelist Nirmal Verma’s time (from the late 1950s through 80s), writers used to encourage and promote each other, but now that feeling is not there anymore,” said Pandey.

Nirmal Verma, who passed away in 2005, was one of the pioneers of Nai Kahani (New Short Story) movement in Hindi literature.

However, vibrant writer communities do exist on social media, where authors promote each other’s work.

Also Read: Hindi writers showdown at Delhi event. Readers take a backseat as egos clash

Turning scrollers into readers

The new wave of Hindi fiction writers are savvy marketers—they are open to interviews, interact with fans at festivals, and often command headlines in local news.

“Nilotpal Mrinal and Divya Prakash Dubey had a blast at the Hind Yug stall, selfies went on throughout the day,” read one headline of a Hindi news channel. “Uncovering the secrets of good storytelling, with Hindi author Divya Prakash Dubey,” read another.

Dubey has almost 150k followers on Facebook and 80k followers on Instagram. He sets Facebook on fire with his posts, especially his one-liners.

“Gale lagane se dukh kam nahi hota, pighalane lagta hai (Hugging doesn’t reduce pain, it melts it away)” reads one photo post on Dubey’s Facebook wall. The accompanying caption invites readers to engage: “Which book is the line from?”

Nilotpal Mrinal enjoys similar social media popularity, with over 161k followers on Instagram and 150k on Facebook.

Fans eagerly await Mrinal’s song releases with the same excitement as his book publications. When he shares his songs, reels, and posters of his events, like Kavi Sammelans, on social media, he always gets an enthusiastic response.

“One of the boys of our village is also part of this. Your presentation is amazing sir,” said a comment on one of Mrinal’s videos on competitive exam aspirants in Allahabad.

Mrinal also uses his social media handles to educate readers about piracy and how it harms authors.

“Writers turned social media users into readers,” said Anu Singh Choudhary. “One user comes to read one writer, but ends up exploring the work of a second one, and then a third one. That’s the power of social media.”

Monika Daksh, 26, said she never considered herself a reader until she stumbled upon a Facebook post about Divya Prakash Dubey’s Musafir Cafe during her second year of college.

“After seeing that post, I bought the book and started reading,” Daksh recalled. “I remember that I forgot to get down at my metro station. I did not know that I could develop a habit of reading this fast.”

After she finished the book, she was hooked. Now, she reads classic writers such as Premchand.

“I’ve read books by Satya Vyas and Manav Kaul and have a huge collection now,” she said. “But if it was not for that one Facebook post, I would not be reading Premchand now.”

Good to see the rise of new talent and the surge in popularity of Hindi literature.

Satya Vyas and Banaras Talkies would’ve completed this list.