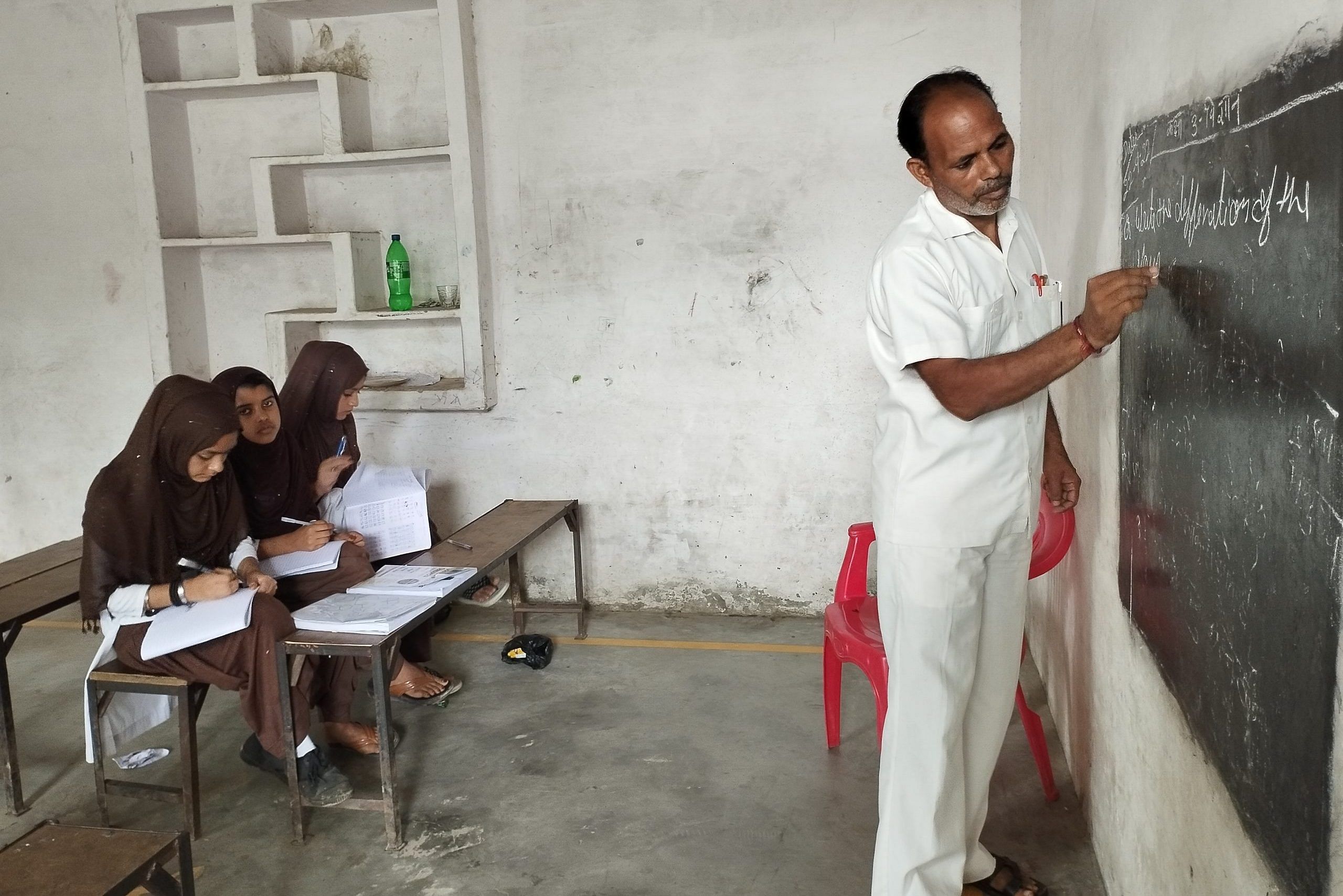

Lucknow: At the Madrasa Islamia School in Lucknow’s Chinhat, Uma Bano is a topper with a knack for science. The 12-year-old wants to become a doctor, but that dream is in danger of vanishing. Her science and math ‘modern’ teachers may not be back next year.

Money to fund her dream is fast running out. The madrasas in Uttar Pradesh are up for multiple overhauls.

Though her teachers were hired as part of the central government’s Scheme for Providing Quality Education in Madrasas (2009) in Uttar Pradesh, they allege that they haven’t been paid their monthly salary of Rs 15,000 since 2017. The state honorarium of Rs 3,000, on which they had been subsisting, was also withdrawn last year.

“My dreams will shatter,” says Bano as she overhears the adults talk about their predicament. It’s all they talk about these days. And not just in madrasas. Teachers have been taking to the streets of Lucknow since December, saying that they are forced to take up menial jobs or gig work to make ends meet. The protest is snowballing into a hot-button issue with Samajwadi Party leaders questioning the Narendra Modi government’s ‘ek haath mein Quran aur ek haath mein computer‘ promise, and the BJP accusing its opponents of playing vote-bank politics.

Where will the thousands of teachers and students go? Has the government given any thought to it?—Dr Iftikhar Javed Ahmed, chairman, UP Board of Madarsa Education

The proceedings at legislative council were mainly focused on the madrasa debate on 8 February, brought forth by Samajwadi Party leaders. The debate has evolved from ‘NRC-like’ investigations to illegal funding to harassment of teachers. Accusations of religious discrimination were hurled at the Yogi Adityanath government by Swami Prasad Maurya and others. “Will investigations run 24x7x365? I have never seen a year-long investigation… you want to stop teacher’s salaries on the basis of allegations, you want to stop the education of children from minorities, teachers are being harassed!”

The 2009 scheme (SPQEM) allows registered madrasas to hire three ‘modern education teachers’ to teach science, math, and Hindi, but it wasn’t renewed by the Ministry of Minority Affairs this year. Primary school modern educators were paid Rs 15,000 a month by the Centre and the state in a 60:40 ratio. Over and above this sum, the Uttar Pradesh government paid them an additional Rs 3,000 a month. Both have been stopped.

Smriti Irani, the minority affairs minister, said in the Rajya Sabha last year that SPQEM was a ‘demand-driven scheme’, which had been implemented until 3 March 2022. And on 8 January 2024, the UP state minority affairs director, C Indumathy, wrote to various stakeholders, including district magistrates, that the UP government is stopping the honorarium because it was a supplementary scheme attached to the SPQEM. This has left the future of at least 21,000 ‘modern’ madrasa teachers in the lurch.

On 29 January, hundreds of teachers from 7,400 registered madrasas in Uttar Pradesh gathered in Lucknow and marched on streets, demanding remuneration for the last six years and the restoration of the scheme

Teachers, who have been staging sit-ins and marches since 18 December, have intensified their demands. On 29 January, hundreds of teachers from 7,400 registered madrasas in Uttar Pradesh gathered in Lucknow and marched on streets, demanding remuneration for the last six years and the restoration of the scheme.

The chairman of Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education, Dr Iftikhar Javed Ahmed said the government hasn’t given a second thought to the situation that teachers and students find themselves in. “The SPQEM embodies the PM slogan of ‘one hand on the Quran and the other on computer’ sentiment. Through it, thousands of madrasa students have been connected with mainstream education. The policy also embodies the PM mantra of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwaas. It must not be stopped,” he said.

The last six years have pushed many Madrasa teachers to do menial jobs to make ends meet. They’re working in puncture shops, carpenter shops, or as delivery executives for food delivery companies like Swiggy and Zomato—Dr Iftikhar Javed Ahmed.

Girls will be affected

At the Madrasa Islamia School in Chinhat, none of the three modern educators—women in their 40s who teach English, Hindi, Mathematics, Social Science, Science—have received their salaries since 2017.

However, even without a salary, the three teachers continued to work at the madrasa. They did so partly in hopes of receiving money from the government and partly for the Rs 3,000 honorarium, which they stopped receiving in June 2023.

“I made do by taking tuitions in the evening, and have been teaching for the Rs 3,000 that the state government had been providing us. I thought since it is government money, it will come to my account. If not today, then tomorrow,” said a Hindi teacher at the madrasa in Chinhat.

I have come to respect doctors since corona. That’s why I want to be one

—12-year-old Uma Bano

Uma Bano’s science teacher has already warned her parents that unless the situation changes, she and the other ‘modern’ teachers are unlikely to continue teaching at the madrasa. This could well mean the end of Bano’s dreams of becoming a doctor and breaking the cycle of poverty while working for the benefit of the community.

“I have come to respect doctors since corona. That’s why I want to be one,” says Bano, who lives in a tiny room in a cramped Muslim-dominated neighbourhood.

Established in 1932, the madrasa needs more than a lick of paint to rescue it from its dilapidated condition. Some classes are held in unfinished skeletons of rooms. There was never enough money to build walls or roofs, says the principal Lal Mohd. The ‘computer lab’ has one desktop installed with Windows XP. The school runs on donations from community members in the neighbourhood and doesn’t charge its students any fee.

Over 3.17 lakh students appeared for their examinations at the registered madrasas in 2016, but this figure dropped to a little over 1.22 lakh in 2021

Bano’s mother Razia cannot afford to send her daughter to a private school, which costs “at least Rs 2,000 a month”. The nearest government school is 5 km away, but the family is hesitant to cover even that distance every day when the madrasa is a stone’s throw from their house.

“My husband is a driver, we struggle to make ends meet. I won’t be able to send my child to any other school,” said Razia. According to Google Earth data, there are 3-4 private schools in the area—Rainbow Pre-school, GD Public Inter College, NWP Inter College, and Kasturba Ballika Vidyalaya.

Modern education is very important for impoverished Muslim communities, especially female students whose families might not send them to any other school. This is a safe environment for female students

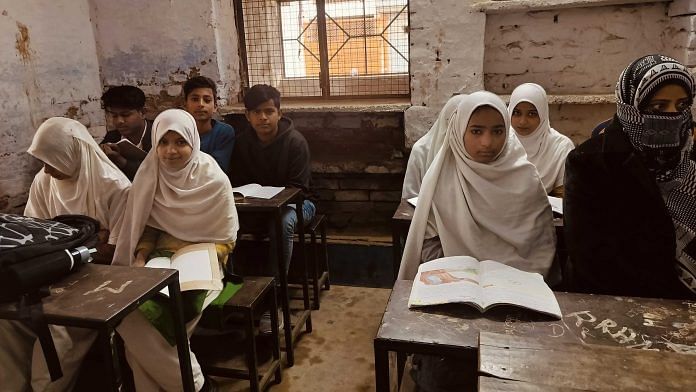

Families here categorically said that in the absence of the madrasa, they won’t send their girls to study “outside” their neighbourhood.

“My family wouldn’t have sent me to school if it wasn’t in our vicinity,” said 22-year-old Zareen Fatima, who studied at the madrasa. However, she hasn’t been able to continue her graduation course for various reasons, mainly because there’s no one to escort her to college. Similar fears were expressed in Karnataka when the state had decided to ban hijab in schools. However, students later appeared for exams without a hijab.

Madrassas are Islamic schools where Urdu, Arabic, and Persian languages are taught along with religious studies. In 2009, the Union government introduced the SPQEM to ensure that students received a well-rounded education. It’s a lifeline for the marginalised Pasmanda community members as well as girls whose parents won’t send them to regular schools.

“Most families here cannot afford to send their children to school, or simply won’t send their daughters to school. It is extremely important for the women of the community to come and study here,” said the English teacher at the madrasa.

There are 12,791 registered and 2,313 unregistered madrasas in Uttar Pradesh, according to the ministry of minority affairs. Of these, 7,400 madrasas have been imparting modern education, representatives of UP Madarsa Board told ThePrint.

Most families here cannot afford to send their children to school, or simply won’t send their daughters to school. It is extremely important for the women of the community to come and study here

But madrasas have been reporting massive dropout rates—61 per cent from 2016-2021, and there are fears the trend will only increase. Over 3.17 lakh students appeared for their examinations at the registered madrasas in 2016, but this figure dropped to a little over 1.22 lakh in 2021, according to the UP Madarsa Board.

“Modern education is very important for impoverished Muslim communities, especially female students whose families might not send them to any other school. This is a safe environment for female students,” said a teacher at Madrasa Islamia School in Chinhat, who did not want to be named. The ratio of girls to boys at the school is 60:40, said the principal. All government-appointed teachers are female.

Promising students here later transfer to a private school in the area in hope of getting a better education.

“My students don’t rush home the minute school is over. They leave for their jobs like working in a shop, or helping out their fathers. Their families cannot afford any other education. This is the only chance they have at building a promising future,” another teacher said on the condition of anonymity.

Also read: Massive dropout, no salaries, UP madrasas gripped in a climate of fear, bulldozer worries

Debates and policy

Islamic education took shape in India in the 10th century. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Fazlur Rahman led the Aligarh movement to introduce modern education in the madrasas. Resultantly, important historical figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Munshi Premchand, and Dr Rajendra Prasad are some exemplary alumni of modern madrasa education. In 1993, the government of PV Narasimha Rao recognised the need for providing modern education at madrasas, which led to the implementation of the 2009 SPQEM scheme.

The future of ‘modern education’ in madrasas has become one of the most hotly debated topics in the UP assembly as well. On 8 February, Samajwadi Party leaders, including Swami Prasad Maurya and Ashutosh Sinha moved a motion to stop regular assembly proceedings to discuss the suspension of the madrasa modernisation scheme, highlighting that affected teachers belong to both Hindu and Muslim communities.

“The state stopped honorarium for teachers in June 2023. This has driven these teachers on the verge of starvation. This proves that the government’s slogan of ‘ek haath mein Quran aur ek haath mein computer; was false,” Member of Legislative Council Ashutosh Sinha thundered in the house. He went on to claim that the lack of remuneration has led to the deaths of four madrasa teachers so far.

According to Maurya, 60 per cent of the affected teachers are Hindus. “We’re not only snatching computers from the hands of young Muslim children, but also books. Why would teachers continue at madrasas without remuneration?” Maurya asked in the council.

As teachers protests intensified, state minister of minority affairs Dharampal Singh addressed the issue in the Legislative Council on 8 February and said the government will release funds under the state honorarium for the teachers. Chief Minister Adityanath’s office has also written a letter to the Centre, asking it to release the pending remuneration.

Singh accused Samajwadi Party leaders of only caring for the Muslim vote. “We want to bring Muslim children to the mainstream so they can become doctors, engineers, scientists. My office and the chief minister’s office have written letters to the central government regarding remuneration. The centre has now discontinued the scheme. We will pay the money due to the teachers so far,” the minister said while addressing the assembly.

Danish Azad, minister of state for minority affairs in the Uttar Pradesh government, too, gave ThePrint similar assurances.

“The Yogi Adityanath government will do everything in its capacity in the interest of our madrasa teachers,” he said. But he did not share any information or discuss if the Adityanath government is coming out with a new policy to fill the lacuna.

Neither the teachers nor the madrasa committees are reassured by these promises. For them, it’s a matter of survival, especially now as they are no longer getting the honorarium.

“Where will the thousands of teachers and students go? Has the government given any thought to it?” said Dr Javed, head of UP Madarsa Board.

Also read: Indian madrasas are thought-influencers. Their funding, modernisation should be priority

Government’s scrutiny

Madrasas have been a deeply political issue for the BJP—Hindu Right organisations have maligned these schools as‘terror factories’. Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has been among the most vocal critics of madrasas, and has closed hundreds of them in his state.

“If they [political leaders] are allergic to the word madrasa, they should remove the name but don’t shut down the scheme,” says Ashrad Ali ‘Sikandar’ Baba, the president of Association of Modern Educators in UP Madrasa. Ali hasbeen spearheading the protests at Lucknow’s Eco Park. “It will not be good for the education of the Muslim community if this scheme is shut down. We are a poor community. This scheme is very important to connect poor young Muslims to the mainstream.”

The trust deficit was further eroded after an alleged incident of sexual abuse came to light in one UP madrassa in June last year, following which the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights requested a survey be carried out across state madrasas. AIMIM president and Hyderabad MP Assaduddin Owaisi called it a ‘mini NRC’ exercise.

“The last six years have pushed many Madrasa teachers to do menial jobs to make ends meet. They’re working in puncture shops, carpenter shops, or as delivery executives for food delivery companies like Swiggy and Zomato,” said Dr Iftikhar Ahmed.

Mohammed Arif, who teaches Hindi at Madrasa Faizi Ali in Lucknow’s Kamal Nagar, works a 13-hour shift — as a teacher in a madarsa and then works as a bike taxi driver for Ola to make ends meet. Even then, the money he brings in is not enough to sustain his family.

His father has asked him to leave the job and refuses to support him, his wife, and their six-year-old daughter, who does not attend school.

“There’s no madrasa in our neighbourhood, and I can’t afford the fees of private schools. I teach so many children but I am unable to send my own child to school,” says Arif.

Dr Javed Ahmed also wrote a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chief Minister Adityanath on 10 January 2024, urging them to continue the scheme and also clear the dues of the teachers. “The government has not given any thought to where these lakhs of students are supposed to go in the absence of the scheme,” he says.

Bano shows off her meticulously made file for English homework, a rose twig cursively flowing on either side of the page. As she shows off her file, her teacher gloats: “Our kids are just as smart as any private school. I hope I can continue to reach them.”

(Edited by Prashant)

Why should the Indian tax payer pay for Islamic schools? If Muslim women want to study, they can be sent to regular schools. If they want to stay regressive in the name of religion, so be it. The common man should not be forced to dance to the whims and fancies of any religion for that matter. And lastly, why hasn’t the Muslim community stepped up to help their own institutions?

बहुत ही सराहनीय

Then WAQF board must help them. Why should Govt give taxpayers money. WAQF board must not hoard money and land.