New Delhi: Chef Manu Chandra changed Bengaluru’s dining scene with Monkey Bar, Olive, and Fatty Bao. Now, he’s changing what it means to be a chef. One moment, he’s coaching young chefs on a flawless hollandaise, the next, he’s consulting on menus or catering high-profile events. He’s not just running a kitchen, he’s a multi-speciality brand.

Chandra is part of a growing wave of chefs who’ve outgrown the traditional restaurant model. They’re moving beyond the ‘celebrity chef’ tag to become chef-entrepreneurs. They are launching not just restaurants but cloud kitchens, catering businesses, and culinary schools.

“A sense of ownership is ingrained deep in everyone in some form of the other, from a cleaner to someone who is working in corporate. Chefs have now tapped into this sentiment,” said 43-year-old Chandra, who has been described as being to Bengaluru’s food scene what Massimo Bottura is to Modena.

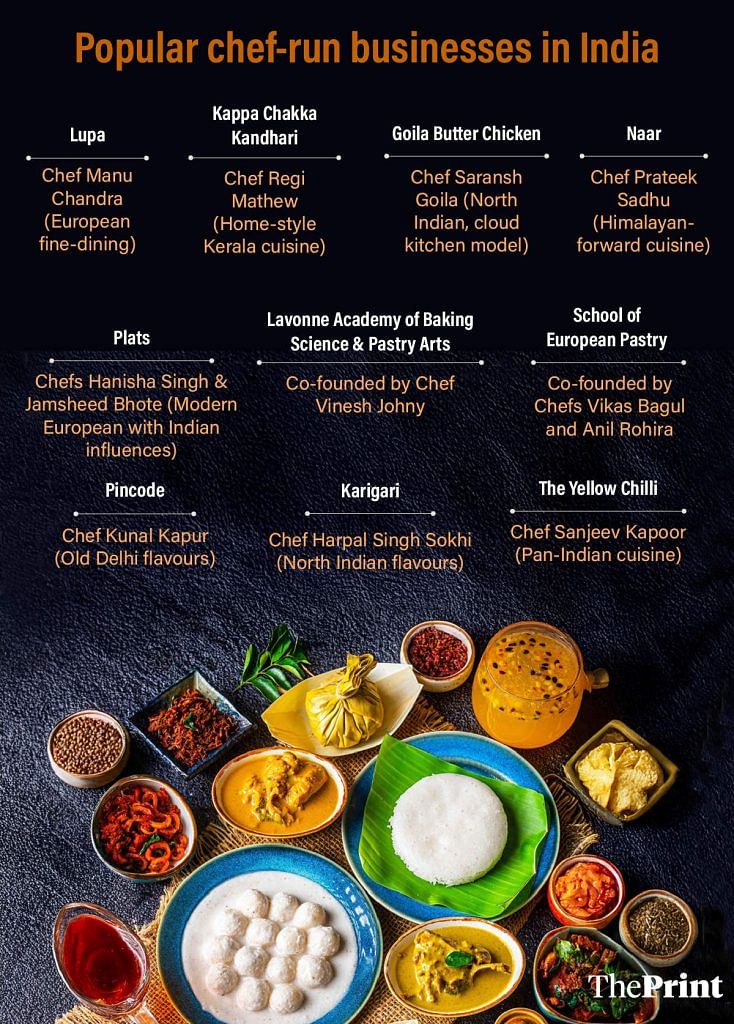

His budding empire, Manu Chandra Enterprises, is a multi-course feast. Launched three years ago, the bootstrapped venture includes Baagh, a craft gin brand; an artisanal cheese line called Begum Victoria; a catering and consulting service Single Thread; and a restaurant arm, Savaa Ser, under which he runs Lupa, his Italian fine-dining space.

His workday is a shuffle between three locations, all in Bengaluru’s CBD—his office on Residency Road, LUPA on MG Road, and the Single Thread Kitchen on Castle Street. Where he’s based depends on the day’s demands.

Decades ago, pioneers like Jiggs Kalra and Sanjeev Kapoor lit the torch, showing how TV and entrepreneurship could turn chefs into stars. But for years, the chef-entrepreneur scene in India felt like a simmer left unattended. Now, a new generation is turning up the heat.

The rules have changed. Cloud kitchens offer agility, social media drives visibility, and investors are eager to pour money into culinary startups.

A huge chunk of people are dining out, exploring new cuisines, and seeking fresh experiences. As long as that appetite grows, so will opportunities for chefs to shine

-Chef Manu Chandra, owner of Manu Chandra Enterprises

Chef-run businesses are now flourishing in every culinary niche. Saransh Goila’s Goila Butter Chicken has built a cult following. Regi Mathew’s Kappa Chakka Kandhari serves home-style Kerala cuisine in Chennai and Bengaluru. And Vinesh Johny’s Lavonne Academy is training the next generation of pastry chefs.

“It’s like the power is finally coming back in the hands where it always belonged — the chefs,” said Chandra.

Valued at Rs 5.69 lakh crore in FY24, the food services sector is expected to reach Rs 7.76 lakh crore by FY28, growing at 8.1% annually. The organised segment, led by quick-service and casual dining restaurants, is expanding even faster at 13.2% annually.

Also Read: Gurugram gets School of European Pastry. Rs 1 crore oven, luxe ingredients, top chefs

When chefs become boss

In 1936, Mumbai’s Cafe Mysore started as a humble street cart in Matunga East. Today, it’s a a beloved hotspot for South Indian food, a favourite of the Ambanis, and even ranked among Conde Nast Traveller’s top 150 restaurants in the world in 2022.

For its third-generation owner Naresh Nayak, legacy brands like Café Mysore, Bengaluru’s MTR, and Delhi’s Kwality have one thing in common: “They didn’t hand over the reins to investors or businessmen. The chefs were always in charge.”

Nayak’s grandfather never partnered with investors; he ran both the kitchen and the business himself.

“He was the OG ‘chef entrepreneur,’” Nayak said with pride.

Cafe Mysore’s story isn’t unique. Generational eateries have always been led by those stirring the pots. This hands-on approach ensured authenticity and control remained intact. Naresh himself claims to have turned down countless expansion offers.

“Can a London tailor replicate their craft in India? Then how can you take Mumbai’s flavours to another city?” he asked. “Businessmen work on Excel sheets, but you can’t run restaurants with it.”

But as money started flowing into the industry, restaurants shifted from craftsmanship to corporate business models. Entrepreneurs hired chefs as employees, stripping them of ownership.

“As chefs, we were always taught to work hard, not smart. But the game has changed. With the global exposure digital media brings, chefs are getting smarter. You can now see how chefs worldwide are thriving—making money, enjoying decent lifestyles, and, most importantly, living life beyond the four walls of a kitchen.”

-Saransh Goila, owner of Goila Butter Chicken

“There was no skin in the game for these chefs,” said Chandra. “They preferred a steady paycheck over diving into the messy—and often brutal—business side of restaurants.”

Behind the scenes, the restaurant world, especially in India, is far from glamorous.

“Paperwork. Bureaucracy. Cops. Staff headaches. It’s not fun,” Chandra pointed out.

For years, restaurateurs focused solely on profitability, leaving chefs with no real stakes in the businesses they ran. But now, that’s changing. More chefs are taking charge of their own futures, and restaurant owners are realising that offering incentives is key to retaining top talent, according to Chandra. But for many chefs, the lure of running their own show is too strong to resist, despite the risks.

And there’s never been a better time to take the leap.

Today, the industry is bursting with opportunities. Valued at Rs 5.69 lakh crore in FY24, the food services sector is expected to reach Rs 7.76 lakh crore by FY28, growing at 8.1 per cent annually, according to the National Restaurant Association of India’s Food Services Report 2024. The organised segment, led by quick-service and casual dining restaurants, is expanding even faster at 13.2 per cent annually.

In the last four to five years, investment has poured in—from jewellers and real estate tycoons to celebrities and billionaires. India is young and hungry.

“A huge chunk of people are dining out, exploring new cuisines, and seeking fresh experiences,” Chandra said. “As long as that appetite grows, so will opportunities for chefs to shine.”

Profitable, chef-owned restaurants are still rare, and there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. Chefs like Manu Chandra, Regi Mathew, and Saransh Goila each have their own ideas on survival.

Passion first, profit later

Regi Mathew the entrepreneur has big expansion dreams. But Regi Mathew the chef isn’t rushing. The burly, mustachioed chef’s award-winning, home-style Kerala restaurant, Kappa Chakka Kandhari, started as a passion project. And he’s just as determined to preserve its “soul” as he is to protect the bottom line.

It all began in 2015 when Mathew swapped stories with friends about their childhood meals in Kerala. As they chatted, they realised how diverse their culinary memories were. It was a lightbulb moment for Mathew about the untapped potential of Kerala’s cuisine.

At the time, he was the chief operating officer and corporate chef for a leading Chennai-based F&B company, but the pull of his roots was too strong to ignore. He quit his corporate role and spent three years travelling across Kerala, visiting nearly 300 homes and 100 toddy shops to soak in the state’s food culture.

In 2018, armed with these insights, he opened Kappa Chakka Kandhari in Chennai, named after three key ingredients of a Kerala kitchen—tapioca, jackfruit, and bird’s eye chillies.

“Kappa Chakka Kandhari pays tribute to the home-cooking of Kerala. The food that is cooked by the mothers, grandmothers and wives,” said Mathew.

Styled like a lively toddy shop, the restaurant elevates local dishes like fish with tapioca, North Malabar-style mussels, avoli nellika masala (white pomfret cooked in a tangy Indian gooseberry masala), and ‘cloud pudding,’ a coconut-based dessert.

Though Mathew collected 800 recipes during his travels, he insists his 100-dish menu is entirely his own—authentic flavours but with a contemporary twist.

“I haven’t copied a single dish,” he said.

A chemistry graduate turned hospitality professional, Mathew started as a trainee at Taj West End in Bengaluru in 1993, mastering Thai cuisine before shifting his focus homeward.

“It was time to do justice to my regional cuisine. To give Kerala cuisine the love and recognition it deserved,” Mathew said. “It is incredibly diverse. The food in the backwaters is entirely different from what you’d find in the plains.”

You cannot sow and immediately get the yield. Let the business grow into a sapling and then into a tree

-Chef Regi Mathew, owner of Kappa Chakka Kandhari

After opening Kappa Chakka Kandhari in Chennai, he launched a second outpost in Bengaluru. Then, he hit the brakes. His experience as COO made the business side manageable, but expansion meant less hands-on involvement, and he wasn’t ready to step back.

“For a new branch to truly replicate the essence of the OG restaurants, hands-on guidance is non-negotiable,” he said.

Mathew lives in Chennai but frequently travels between both restaurants. He’s still an active chef—developing menus, creating new dishes, and conceptualising food festivals. His business partner, Augustine Kurien, also travels between the two cities, while a strong kitchen and front-of-house team handle day-to-day operations.

Other than running his restaurants, Mathew hosts Chef’s Table events, bringing top chefs together to cook traditional dishes. He also leads the Centre of Excellence at Orkla India—the parent company of MTR Foods and Eastern Condiments—where the team researches regional Indian food.

“I am spending more time on understanding and exploring regional Indian food. That’s the goal of my life as a chef-entrepreneur,” he said.

Beyond the kitchen

Some chefs spend decades honing their craft before opening a restaurant. Others don’t wait that long. And some take a route where there’s barely any cooking involved.

For Vinesh Johny, the path was education. In 2011-12, fresh out of Christ College’s hotel management programme, he specialised in pastry but quickly realised his skills weren’t enough. At the time, the only way to get top-tier pastry training was to go to France, Australia, or the US. But the cost was prohibitive.

And so, he decided to help fill India’s pastry training himself.

In 2012, at just 24, he co-founded Lavonne Academy in Bengaluru with his college professor Avin Thaliath and colleague Lijo Chandy. They bootstrapped it with savings and parental loans, starting with just three students.

Now, Lavonne trains 1,660 students annually, including 160 in its flagship six-month bakery and pastry programme.

“We were among the first pastry schools so we didn’t struggle much, as people were looking for it. Our popularity grew via word of mouth,” he said. Between the school’s and founders’ Instagram pages, Lavonne has over 5 lakh followers.

Lavonne opened a second school in Delhi last year and has also expanded into cafés, with four outlets in Bengaluru and one in Delhi.

Though Jonny doesn’t have a business background, he says his mission plan saw him through.

“Honestly, I never thought much about the business side of things. My only goal was to bring a world-class pastry school to India,” he said. “As for the rest, I think I just made the right calls when the time came.”

Another young chef who took an unconventional track to culinary stardom was 37-year-old Saransh Goila.

After dabbling in hotel management, his first venture, a catering company, didn’t generate the returns he hoped for.

“I was too young to be an entrepreneur and be a captain of my own ship,” Goila said.

Despite his lack of experience, he then tried to build a career as a celebrity chef. Acting classes helped him sharpen his skills, and soon, he was chosen for Food Food Maha Challenge, hosted by chef Sanjeev Kapoor. After winning the show in 2011, he landed a food road trip show, Roti Rasta Aur India, and began participating in food pop-ups across the country. But what really got him noticed, ironically, was his food.

His butter chicken changed everything. When he started serving it at pop-ups, it quickly gained high-profile fans, including Priyanka Chopra, Uday Chopra, and Nargis Fakhri.

“I had no idea they’d tried it until my Twitter (now X) blew up one night,” Goila recalled.

That viral moment pushed him to start a cloud kitchen in 2016, with no real business plan—just demand.

“The name wasn’t planned either. Fans started using the hashtag #GoilaButterChicken, so I went with it,” he said.

Goila scaled fast, from a 200-sq-ft central kitchen in Mumbai to 107 locations nationwide now. Today, GBC serves more than 40 North Indian dishes, including tandoori chicken, keema pav, and paratha. But the butter chicken prevails. In 2018, George Calombaris of MasterChef Australia even called it the “best butter chicken in the world.”

Goila himself is less hands-on in the kitchens these days. He designed the menu and trained the staff, but now he only oversees operations. He’s busy with TV appearances, sharing recipes with his 1.5 million Instagram followers, and hosting pop-ups around the country.

“As chefs, we were always taught to work hard, not smart. But the game has changed,” Goila said. “With the global exposure digital media brings, chefs are getting smarter. You can now see how chefs worldwide are thriving—making money, enjoying decent lifestyles, and, most importantly, living life beyond the four walls of a kitchen.”

As far as he is concerned, sweating behind a stove is overrated.

“The romanticism of ‘a chef belongs only in the kitchen’ doesn’t resonate with me,” he said.

Also Read: Korean BBQ is an old fad. There’s a Turkish takeover in Delhi’s food scene

Many hats, many recipes

For every restaurant that opens, another shuts. Years of effort can fall apart with a single bad review. Profitable, chef-owned restaurants are still rare, and there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. Chefs like Manu Chandra, Regi Mathew, and Saransh Goila each have their own ideas on survival.

Chandra doesn’t sugarcoat the challenges, but to him everything boils down to priorities.

“I’m both a chef and a businessman. It’s my responsibility to keep my business running and ensure my employees can provide for their families,” he said. “If I let my ego run the show or waste time worrying about every so-called food critic with a blog or a YouTube channel, do you think I’d get anything done?”

He sticks to his vision, no matter what the latest fads are. But many chef-entrepreneurs, he says, fall for “idiotic market experts” who convince them to stray from what made them successful in the first place.

“They’ll tell you, ‘You’re the best thing to happen since sambhar.’ And somehow, they manage to convince you to change your cooking style—often in ways that don’t resonate with a broader audience,” he said. “Ego doesn’t feed people. Food does.”

Constructive criticism from customers, however, is something that chefs like Chandra and Mathew value—up to a point.

“As chefs, we must be receptive to feedback, especially from customers—they’re a reflection of our work. But in the end, it’s your conscience that should guide the final decision,” Mathew said.

For him, patience is key. Slow, steady growth beats gimmicks. Flashy presentations and dramatic table-side theatrics might grab attention and bring in customers in the age of social media, but that’s not enough to keep them coming back for more.

“You cannot sow and immediately get the yield,” said Mathew. “Let the business grow into a sapling and then into a tree.”

Goila, however, thrives on the spectacle.

“Chefs are entertainers,” he said, pointing out that he took lessons at Barry John’s Acting Studio after his first catering business folded in 2011.

“I knew I wanted to be a food content creator,” he says. “But I quickly realised that to truly succeed, I needed to be more than just a chef—I needed to think like an actor, director, and producer.”

This acting course became the ‘missing link’ in his culinary career.

“It taught me how to speak, act, shoot, and edit videos—skills I didn’t know I needed,” said Goila, whose TV appearances helped him build an audience and set up pop-ups before his butter chicken took off.

To succeed in business, he argues chefs need to reinvent themselves constantly.

“Learn accounting, management, people managing skills, finance,” he said. “Whatever it entails to be an entrepreneur, don’t be shy to learn it.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)