Chennai: A vast metal canopy rises over the Sivagalai archaeological site in Tamil Nadu’s Thoothukudi district, shielding a grid of trenches that cut deep into the past. Excavations that started five years ago have uncovered the remnants of a civilisation that existed around 3,200 years ago, challenging the idea that India’s civilisational story started in the north.

Here lies Tamil pride and a renewed push to prove the early origins of Tamil history. A few weeks ago, Chief Minister MK Stalin released a report with a startling revelation: Tamil Nadu had entered the Iron Age while North India was still in the Copper Era. The findings suggest that iron was in use as early as 5,300 years ago—even older than the civilisation confirmed at Sivagalai.

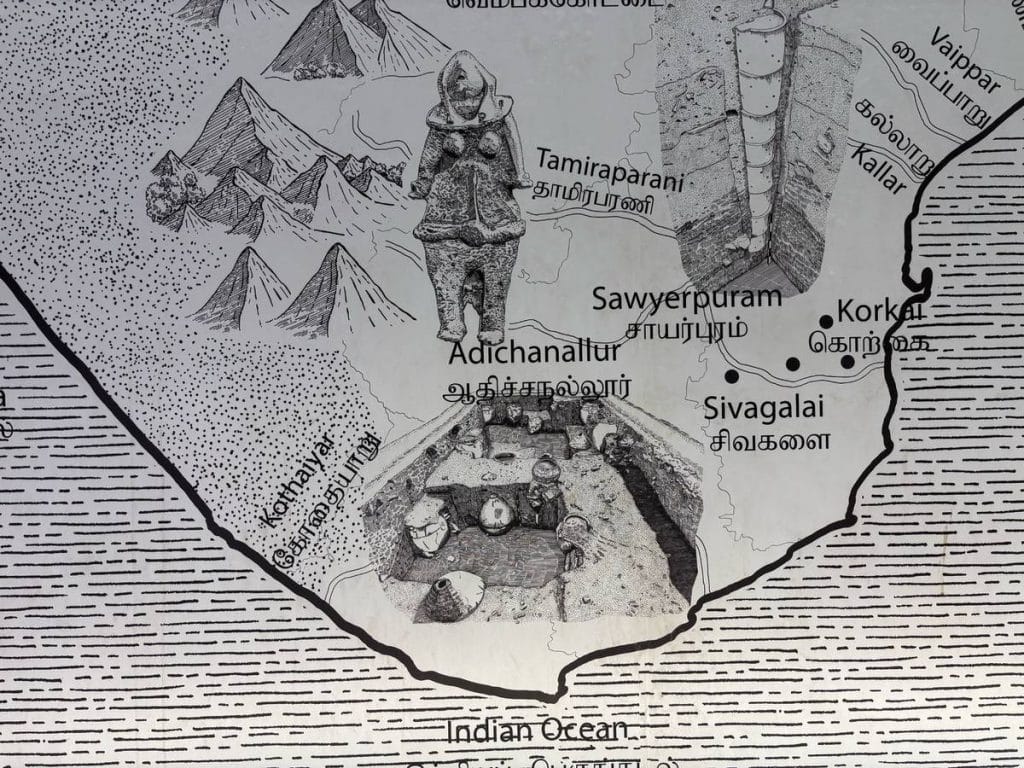

The discovery of iron tools and rice grains from burial urns at Sivagalai has pushed back the Iron Age timeline by millennia and revealed that people were farming in Tamil soil as early as 1155 BCE. This is where the Thamirabarani River once flowed. Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions on excavated potsherds have also shifted the Tamili script’s known history, dating it to 685 BCE, or 2,700 years ago—100 years earlier than the Keezhadi site, where Tamil-Brahmi was previously dated to 580 BCE.

“Not many knew that we were standing on a treasure trove when we began the excavations in 2019,” recalled Prabhakaran, archaeology officer and Sivagalai site director from 2019 to 2022.

If the dazzling archaeological findings withstand a robust peer review process, the centre of gravity of ancient India is likely to shift away from the Harappa-obsessed north and northwest to the south. The buzz that the Sivagalai dig has generated since is unprecedented. History has now captured the Tamil zeitgeist.

As of 29 January, there have been 200 visitors since the start of this year to witness the place of ancient Tamil habitation.

The site watchman, Nataraj, claims it isn’t just local residents—people from across the country have been turning up.

“We never knew the importance of the site until people started visiting it,” he said.

The new Iron Age findings have opened a can of worms as they predate the traditionally accepted timeline of the Iron Age in India— until now, the earliest iron use was thought to be 1800 BCE, based on findings from Malhar in Uttar Pradesh’s Sant Kabir district and elsewhere.

Professor of Archaeology at Karnatak University, Ravi Korisettar, told ThePrint that the dates could be even earlier what is known today.

“Whatever they have found is the age of the materials, but we don’t know when they were introduced and when they began to make iron objects. So, it may be much earlier than the known dates,” he said.

Stalin has never let go of any opportunity to assert the Dravidian identity—or to frame history almost as a rivalry of civilisations.

Also Read: Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age report is a turning point in Indian archaeology. It needs more research

Excavations as a battleground

As with everything in India, archaeology comes with politics.

The archaeological community is excited about the new findings, but also wary of how they are being politicised. Every announcement has come straight from DMK president and Tamil Nadu CM MK Stalin.

Releasing the report on 23 January, Stalin framed the carbon dating evidence not just as a discovery but a matter of regional identity.

“Not just in India, I declare to the world that iron began on Tamil soil. Iron ore technology was introduced in the Tamil soil 5,300 years ago,” he declared. “Those who mocked us that literature can never become history have now stumbled with the way we have been proving our history scientifically.”

This is not the first time that Stalin has asserted Tamil Nadu’s primacy in India’s past. Since taking office in 2021, he has repeatedly said that the history of the Indian subcontinent will be rewritten from Tamil soil, with scientific proof gathered by his government.

His recent $1 million reward for deciphering the enigmatic Harappan script is part of the same ongoing political project of Tamil cultural pride. Although this template of Dravidian pride politics is several decades old, it has got fresh impetus as the DMK takes on the BJP’s brand of north-centric cultural politics more and more.

We understand that the north has always seen or treated the south with a step-brotherly attitude. But that does not mean you should also reciprocate it in the same way. That was the major cause of worry about the recent findings

-Kurush F Dalal, archaeologist

No BJP leader that ThePrint spoke to in Tamil Nadu would comment on record about the findings, but they all accused the DMK of trying to create a North-South divide.

“Although we cannot solve present problems by revealing the ancientness of the past, it would be beneficial in understanding the political complexities of the present,” said political commentator A Perumal Mani.

He argued that beyond politics, the ongoing research had national and global importance.

“This is a finding from the country, showing the world that a habitation existed here and that iron existed in the southern part of India around 5,300 years ago. This would not help any party politically, but advancing scientific research in archaeology is important for any government,” Mani added.

North-South digs

Stalin’s quest is not sitting well with some archaeologists outside southern India.

While acknowledging that the report on Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age is backed by solid evidence from multiple laboratories, archaeologist and museum consultant Kurush F Dalal voiced concerns over science being used as a political tool.

“We understand that the north has always seen or treated the south with a step-brotherly attitude. But that does not mean you should also reciprocate it in the same way. That was the major cause of worry about the recent findings,” he said. Many archaeologists worry that their work could get locked in a north-south battle over history.

Dalal stressed that more evidence of Iron Age sites was needed to establish a continuous record of habitation and definitively prove that iron was prevalent in South India.

The authors of the Iron Age report, R Sivananthan and Professor K Rajan, had also noted in their study that future excavations would strengthen their existing findings.

“The metallurgical analysis of iron objects from the excavated sites and future excavations in iron ore-bearing zones may further consolidate or strengthen these findings. Let us hope and wait for future evidence,” the authors said in their report.

There’s no doubt Keezhadi is a significant find, showing a well-established civilisation from the 6th century BCE, with artifacts proving that the Tamil Brahmi script preceded Ashoka’s Brahmi. But similar discoveries in Porunthal in 2011 went unnoticed without political interest

-Senior archaeologist R Jagadeesan

The state’s archaeology department is already moving forward on this front.

“Whatever we have done so far is scientific, and now we’ve received suggestions to subject the iron objects to metallurgical analysis as it was done in Telangana. We are going to do that as well,” said IAS officer and state archaeology commissioner T Udhayachandran.

A senior minister in the state cabinet dismissed accusations of politicisation, insisting that the government had a duty to inform taxpayers about its work.

“The archaeological excavations are done by the state government by sanctioning government funds, which is people’s money. So, we are liable to tell the people about the outcome of such excavations,” he told ThePrint.

Before 2017, Tamil Nadu capped excavation budgets at Rs 3–5 lakh per site. This rose to Rs 31 lakh in 2019. After the DMK took power in 2021, it allocated Rs 35 crore to archaeology, with Rs 5 crore annually for eight sites.

A gamble on the past

In 2019, when archaeologist Prabhakaran laid out his plan to excavate Sivagalai, the first reaction was scepticism.

“Can you really do this, or are you deceiving me?” archaeology commissioner T Udhayachandran—now also the finance secretary—asked him.

Udhayachandran’s doubts weren’t about the site’s potential but about execution. Tamil Nadu had only recently started increasing excavation budgets, and this was one of the first big projects under the state’s expanded archaeology push.

Prabhakaran reassured Udhayachandran that he was prepared for the task ahead, but soon, doubts crept in.

“We found nothing for days at the first site, and I was concerned I might have picked the wrong spot,” Prabhakaran recalled.

Then, after a tense wait, they unearthed their first urn at what they named Site A1.

“The villagers were thrilled, and rumours were spreading that we had discovered a treasure of gold and other valuables,” Prabhakaran said.

But excitement soon turned to concern. He and his team received a call warning them about suspicious people around the site.

“We had put so much effort into finding that first urn, we couldn’t let it go. So, I and the local history teacher, Manickam, went to guard the site overnight without sleeping,” he said. Manickam was as invested as Prabhakara—he had helped identify the site years ago.

The Keezhadi excavation changed Tamil Nadu’s historical landscape. ASI began excavations there but halted them citing a “lack of significant findings”. Amid a political backlash, Tamil Nadu’s archaeology department took over. By 2019, Keezhadi had become a political symbol of Tamil history’s ancient roots.

Bigger budget & Keezhadi factor

The Tamil Nadu government only began digging at Sivagalai in 2019, but history teacher A Manickam had been talking about historical remains there for over a decade.

“I have been picking up pottery, iron tools, and other items during my morning walks since the early 2000s. But I couldn’t get through to any officials. I only managed to send letters to the archaeology department,” Manickam told ThePrint.

That changed in 2018 when Manickam joined the district-level textbook correction committee and finally got an audience with IAS officer Udhayachandran, then school education secretary.

“I kept telling him about my findings from my walks and pushed for an archaeological study,” Manickam said.

His persistence paid off, though not immediately.

This is a finding from the country, showing the world that a habitation existed here and that iron existed in the southern part of India around 5,300 years ago. This would not help any party politically, but advancing scientific research in archaeology is important for any government

A Perumal Mani, political commentator

That same year, Udhayachandran was moved to the archaeology department. When the government sought new excavation sites, he suggested Sivagalai, given its proximity to Adichanallur, another major archaeological zone. Prabhakaran was chosen to lead the dig, and funding was sanctioned in 2019—an unprecedented Rs 31 lakh.

At the time, the AIADMK government had already begun prioritising archaeology, with Keezhadi (or Keeladi) in Sivaganga at the centre of this shift.

A Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology (TNSDA) official recalled how a casual conversation between Udhayachandran and an ASI official at Keezhadi in 2017 reinforced the need for bigger budgets.

Udhayachandran had asked: “You have dug in many places at one site, whereas our officers only dug in two places in Alangulam, Ramanathapuram district. Is ASI’s research different from the state department’s?”

The ASI official replied sarcastically: “With the budget you provide, that’s all they can do. Digging in two places is a lot with the money you give.”

This, the TNSDA official said, made Udhayachandran acutely aware of how little Tamil Nadu was investing in archaeology and to push for more funds, starting with Keezhadi in Sivaganga district.

The site had already changed Tamil Nadu’s historical landscape. ASI began excavations there in 2014, but abruptly halted them in 2017, citing a “lack of significant findings”. Amid a political backlash, Tamil Nadu’s archaeology department took over in 2018 and uncovered more evidence of an urban, literate civilisation dating back to the Sangam era (6th–3rd century BCE). By 2019, Keezhadi had become a political symbol of Tamil history’s ancient roots.

In the wake of Keezhadi, the DMK government opened its purse strings for history like never before.

Before 2017, Tamil Nadu capped excavation budgets at Rs 3–5 lakh per site. That gradually increased to Rs 31 lakh per site in 2019. However, after the DMK came to power in 2021, the government allocated Rs 35 crore to its archaeology department, with Rs 5 crore annually for excavations at eight different locations.

The Dravidian pride project

It all goes back to the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Stalin has never let go of any opportunity to assert the Dravidian identity—or to frame history almost as a rivalry of civilisations.

Last September, he paid homage to John Marshall, who first announced the Indus Valley Civilisation in 1925, and thanked him for linking its material culture to “Dravidian stock”

Months later—at a 5 January conference commemorating the centenary year of Marshall’s announcement—he announced the $1 million prize for decoding the Indus script and declared that there was now a “new Iron Age”.

Even before this, in 2022, the DMK government announced that Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age dated back 4,200 years and was the oldest in India, based on artefacts from Mayiladumparai in Krishnagiri district.

Unlike the previous AIADMK government, where archaeology remained in the background, Stalin has made it clear that all major carbon-dating discoveries will be unveiled by him personally.

This politics of pride goes back a long way in Tamil Nadu. And DMK has been at the heart of it.

While social reformist Periyar asserted the identity through rationalist ideas, former Chief Minister CN Annadurai and M Karunanidhi or ‘Kalaignar’ championed it through Tamil literature. And now Stalin is advancing it through archaeology and scientific proof—the next step in something his father Karundanidhi started.

“Kalaignar was instrumental in the excavation of Kaveripoompattinam that went under the sea about 50 years ago,” said writer TS Subramanian, who has authored books on archaeology. He added that it was under Karunanidhi’s tenure the grand Valluvar Kottam monument in Chennai and the 133-foot-tall Thiruvalluvar Statue in Kanyakumari were built.

“When the world classical Tamil conference was held in 2010 in Coimbatore, archaeological findings were also displayed,” he said.

A former civil servant who worked closely with Stalin between 2006 and 2011 also recalled how Karunanidhi asserted Tamil identity by celebrating history with lavish state-backed events.

“It was because of Kalaignar that there was a grand exhibition on the Cholas during the 1000th anniversary celebrations of the Thanjavur temple (in 2012), built by Raja Raja Chola,” he said.

During the DMK’s first government in 1968, then Chief Minister CN Annadurai organised the Second World Tamil Conference in Chennai. As part of the event, 10 statues of Tamil literary greats were erected on Marina Beach.

A senior IAS officer in the Union government noted that Tamil Nadu was the first state in India to establish its own archaeology department.

“In 1961, under the Congress regime, Tamil Nadu got its own archaeology department. Until then, the ASI had been taking up all the archaeological research work across the country,” he said.

And then came Keezhadi. It was AIADMK that shaped and shepherded the dig’s contribution at first.

AIADMK spokesperson RM Babu Murugavel told ThePrint that his party ensured the excavations were restarted after being stalled by the Union government in 2017.

“Had the AIADMK government not initiated the Keezhadi excavations, we wouldn’t have known that Tamil is 2,600 years old,” he said. “Similarly, the Sivagalai excavations also began under AIADMK. If you look at the lab reports regarding the Iron Age announcement, some results were out in March 2021, but the researchers revealed them only now.”

A ‘turning point’

The Keezhadi excavation has had its share of stops and starts. ASI officers publicly bickered and disagreed over its importance. And each time they did, the Tamil identity project got more political, cultural, and academic fuel.

“There was no connection between Keezhadi and the Indus Valley Civilisation. The site cannot prove that traders lived there. It’s too early to draw any conclusions,” PS Sriraman, superintendent at ASI, told the media on 30 September 2017, announcing the end of excavations.

But this contradicted his predecessor. Amarnath Ramakrishna, the ASI superintendent before his transfer in March 2017, had argued that Keezhadi’s burnt brick structures suggested an urban civilisation had existed there.

“We have found continuous constructed walls of 10 to 15 metres in length. We haven’t found such lengthy walls in any other site in Tamil Nadu. We have also found structures of open and closed drainage networks, which are clear indications of the prevalence of an urban civilisation,” Ramakrishna told the media.

He also revealed that the Union government had not granted permission to carbon-date Keezhadi’s excavated samples. What’s more, the decision to halt excavations came just months after Tamil Nadu’s January 2017 protests against the Union government’s ban on Jallikattu, a traditional bullfighting sport.

The Keezhadi controversy played into the perception that the Centre wasn’t cooperating with Tamil Nadu. And it sparked a renewed drive to assert Tamil identity

“That was the turning point where archaeology and state politics converged,” noted the Keezhadi archaeological site officer.

However, Tamil historians and archaeologists had been quietly making discoveries and connecting the dots for years. Not all of it was informed by politics. Many didn’t wait for political signalling, with civil servants and researchers continuing their work even when the state showed little enthusiasm.

Senior archaeologist R Jagadeesan, who retired about seven years ago, pointed out that politics brought Keezhadi into the public eye, while earlier discoveries were largely ignored.

“There’s no doubt Keezhadi is a significant find, showing a well-established civilisation from the 6th century BCE, with artifacts proving that the Tamil Brahmi script preceded Ashoka’s Brahmi. But similar discoveries in Porunthal in 2011 went unnoticed without political interest,” he said.

The Porunthal excavation, conducted in 2009 by Professor K Rajan with support from the Central Institute of Classical Tamil and the ASI, revealed rice paddy from 450 BCE, confirming a settled, agrarian presence in the region.

Still, an archaeology department official who worked at Keezhadi insisted that the excavation itself had not been politically motivated.

“The Keezhadi findings were made public during the AIADMK’s tenure, but without much promotion from the Chief Minister. It was handled by minister Ma Foi Pandiarajan,” the official said.

He also credited civil servants with keeping the project alive, regardless of political shifts.

“After ASI stopped, the state government initially showed little interest. It was the bureaucrats who reignited the excavations, sending samples abroad to confirm Keezhadi’s 2,600-year-old civilisation,” the official added.

Museum race

After the Keezhadi discoveries, the DMK government didn’t just publicise the findings—it built a Rs 18 crore museum to showcase them.

The exhibits include gold ornaments, ivory combs, coins, seals, and semi-precious stones, as well as interactive displays and selfie spots.

Inaugurating the museum on 5 March 2023, Stalin reiterated that South India was central to the subcontinent’s history.

Years earlier too, he had written to the central government advocating for the museum and arguing that the “history of India should be seen from the perspective of Tamils”. And once it was built, he urged the Tamil diaspora to visit this “symbol of our history.” In January 2025, Stalin laid the foundation for another open-air museum at Keezhadi to showcase brick structures and wells.

Now, there’s a Centre-state race to build museums, according to the senior TNSDA official.

“The Union Government’s ASI abandoned Keezhadi in 2017, but the state continued. Now, both are racing to build museums to display findings from Adichanallur, Sivakalai, and Korkai, part of the Porunai habitation,” the official told ThePrint.

In August 2023, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman inaugurated an on-site museum at Adichanallur in Thoothukudi, but reports claim it’s in a state of neglect. In May that year, MK Stalin also laid the foundation for a Rs 33.02-crore Porunai Museum project in Tirunelveli.

But for now, it’s Keezhadi that has captured public imagination. It pushed the known age of the Tamil script back to the 6th century BCE, a century earlier than previously thought.

“This proves a high level of literacy in Tamil Nadu by the 6th century BCE. Scholars believed the second urbanization didn’t occur here as in the Gangetic valley, but Keezhadi suggests otherwise,” states the excavation report.

Museum officials report that half of their visitors are from Tamil Nadu, 30 per cent from other states, and 20 per cent are international.

Tamil families from abroad are visiting it to get in touch with their heritage.

“It’s fascinating to learn about Tamil history, land, and culture,” said C Wanidah, a Tamil from Malaysia, who visited with her children. “Social media videos inspired our visit. Even though I grew up in Malaysia, I want my kids to know their Tamil roots.”

Even Tamil Nadu schoolchildren are convincing their parents to visit after studying Keezhadi in class. CP Bavisha, a class XI student from Chennai, persuaded her parents to go.

“We are proud that such a site exists in our Tamil Nadu. The Iron Age revelations have made us even more eager to explore how our ancestors lived,” said C Periyasamy, Bavisha’s father.

Also Read: Ratnagiri to Ramanathapuram—engineers, teachers, fishermen are ASI’s unsung warriors

Adichanallur—India’s ‘neglected’ dig

The Harappa-centric focus of Indian historiography continues to rile many. And this is not new.

Indus Valley Civilisation researcher and former IAS officer R Balakrishnan pointed out that the Dravidian hypothesis has been around for 100 years, while the Indo-Aryan hypothesis has been discussed for 99.

“In 1924, John Marshall introduced the Indus Valley Civilisation to the world, and in the same year, December, Suniti Kumar Chatterji wrote that IVC was a Dravidian civilisation. The Indo-Aryan hypothesis only emerged in 1925,” he said.

In a Modern Review article titled ‘Dravidian Origins and Beginnings of Indian Civilisation’, Chatterji cited the 1904 Adichanallur excavations in Tamil Nadu to advocate what is now called the Dravidian hypothesis. He also dismissed the idea of Indo-European or Sumerian origins to the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Adichanallur was one of India’s earliest archaeological digs. In 1876, German archaeologist Fedor Jagor unearthed iron tools and weapons there and shipped them to the Berlin Museum. In 1904, superintending archaeologist Alexander Rea carried out further excavations at this burial site.

Balakrishnan argued that Adichanallur was actually the first site excavated under John Marshall’s orders, well before the Harappa and Mohenjo-daro digs of 1921-22.

“Marshall came to India at the age of 26, visited Alexander Rea in what is now Trichy, and instructed him to excavate Adichanallur. Despite many artifacts being unearthed, none were studied and they remained in Chennai museum,” he said.

Marshall’s departure left many leads cold and attempts to pick them up later saw limited traction.

In 1935, KN Dikshit—who later became ASI director-general—brought up the Indus Valley Civilisation’s connections to Adichanallur and the ancient port site Korkai during a lecture at Madras University.

“[Dikshit] told the gathered archaeologists that Korkai and Adichanallur might be contemporary with or slightly later than the IVC. However, these remarks were largely ignored until they were published in 1939,” Balakrishnan said, referring to the essay collection Prehistoric Civilization of the Indus Valley.

Dikshit expressed hope that “Madras investigators” would unearth antiquities “proving the extension of this civilization further to the south”. But it would take decades for real progress.

ASI don’t dig in Tamil Nadu, and even when they do, they don’t release reports for reasons known only to them. It is in this backdrop that I say the current archaeological studies in Tamil Nadu have taken the right path

–Indus Valley Civilisation researcher and former IAS officer R Balakrishnan

It was only between 2004 and 2006 that ASI superintendent Dr T Satyamurthy resumed excavations at Adichanallur—over a century after the initial dig. This hit a wall as well.

“Despite uncovering human skeletons, nothing substantial resulted from the excavation. It took an activist’s legal battle to get even a basic report published, which finally happened in 2018,” Balakrishnan said, calling the delay “archaeological apathy” and “criminal negligence”.

The delay has been partly attributed to Satyamurthy retiring in 2006. The data sampling of artefacts and the report only came after a PIL by writer Muthalankuichi Kamarasu.

The report concluded that rice grains from urn burials dated Adichanallur’s ancient settlers to the early first millennium BCE and confirmed they cultivated paddy and green gram.

“ASI don’t dig in Tamil Nadu, and even when they do, they don’t release reports for reasons known only to them,” said Balakrishnan. “It is in this backdrop that I say the current archaeological studies in Tamil Nadu have taken the right path by proving the ancientness through scientific evidence.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Somebody should shove those rusty rods in Stalin and his sons ass

Where is the politics in this ?

A leader talking with pride about his people’s ancestry is not politics. He has not talked about North-South matters or claimed superiority.

I am glad that someone is at last taking such discoveries to the world. These discoveries belong to India and raise India’s stature in the world.

You are creating politics out of nothing.

The pace at which things are going, tommorow Stalin may announce he found Kumari Kandam ?