Buldhana (Maharashtra): Bondgaon, a small village about 70 km from Buldhana, has become a meeting ground for scientists from India’s top research institutes. To find out why villagers are balding at an alarming rate. It’s a medical mystery. Scientists from the Indian Council of Medical Research, AIIMS, the Hyderabad Institute of Life Sciences, the district medical board, and Bawaskar Hospital and Research Centre are all scratching their heads over what happened.

It all began with sudden, unexplained hair loss. Now, painful scabs on the scalp, dark patches under the nails, blurred vision, unexplained weight loss. Both the villagers and scientists are gobsmacked.

Top scientists from across India have walked its dusty, unpaved lanes, collecting samples of everything—soil, water, even the villagers’ blood and urine.

On a winter morning in early January, residents noticed hair falling off in clumps. Over 400 people—young and old, men and women—from 18 villages in Buldhana district suddenly went bald overnight. The panic was instant. The embarrassment came next.

But months later, scientists still can’t say what exactly hit the people of this village and 17 others nearby. District and medical officials are silent. Scientists aren’t sure if it was contaminated water, a viral infection, or—as one early report suggested—an overdose of Selenium in wheat distributed through the public distribution system (PDS).

“Some of the younger ones grew their hair back, but patients like me are still experiencing slow hair growth. To add to my misery, I am now experiencing new symptoms. Now that summer is here, the scabs on my head hurt a lot,” said 70-year-old Shantabai Andurkar, fidgeting with the end of her saree as she resisted the urge to scratch her scalp.

She is not alone. Most patients in Bondgaon, Hingna, and Kalwad who suffered sudden hair loss in January are now facing a second wave of symptoms. Some are even showing isolated problems like weight loss and skin rashes.

District and medical officials are silent. Scientists aren’t sure if it was contaminated water, a viral infection, or—as one early report suggested—an overdose of Selenium in wheat distributed through the public distribution system (PDS).

Also read: Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak in Pune: What you need to know about this rare nerve disorder

How the Buldhana hair loss crisis began

Eleven-year-old Supesh Digamber calls himself Virat Kohli’s “biggest fan”. He copies Kohli’s cricketing style—and his hairstyles too. He had been going to the local barber for tapered sides and used hair gel to spike up the top—until he was able to grow a beard like Kohli.

But on 5 January, after a game of cricket, he came home, removed his cap, and saw it lined with strands of his hair. His mother, Nirmala, ran her fingers through his scalp to check—only for more hair to come off in her palm. A few swipes later, Supesh was nearly bald.

As he broke into a loud wail watching his hair come off in clumps, Nirmala slapped him hard for using copious amounts of gel to imitate Kohli’s hairstyles.

“I did not know what to do,” she said. “I called his father immediately. We didn’t know if it was something he ate or a side effect of all the styling products.”

Soon, it was clear that Supesh wasn’t the only one. On 2 January, three women from a single family—32-year-old Ratna, 14-year-old Vaishnavi, and seven-year-old Priya Vinayak—were the first to report sudden hair loss. At the district hospital, doctors blamed it on a shampoo.

But the symptoms spread like wildfire. Within two days, 35 people from Bondgaon had lost their hair. Over the next week, the number snowballed—more than 400 residents across 18 villages in Buldhana district were affected.

“People started coming in worried about what was happening to them and their family members,” said Rameshwar Tharkar, the village sarpanch. “I made some calls to the district officials, and that’s how we realised more villages were facing the same thing. After Covid, this was the biggest medical scare we have had.”

Also read: Young Indian men are battling a chronic hair fall problem. Here’s how they can reverse it

A village turned lab

In the days that followed, Bondgaon became the epicentre of what local residents called the ‘balding virus’. Roads leading to the village were soon swarmed by ambulances, media vans, and research teams arriving one after another.

Scientists from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), AIIMS, the Hyderabad Institute of Life Sciences, the district medical board, and Bawaskar Hospital and Research Centre visited Buldhana between January and February, collecting everything from hair samples to groundwater.

Padma Shri awardee Dr Himmatrao Bawaskar, a physician in Mahad, Raigad, was among the first to identify a possible culprit: dangerously high Selenium content in the wheat distributed via PDS. Selenium is a mineral the body needs in small amounts—but in excess, it can be toxic.

Dr Bawaskar’s tests found Selenium levels in the wheat to be 600 times higher than the permissible limit.

“Along with hair loss, patients were also experiencing high fever, vomiting, headache, excessive itching and dizziness,” he said.

The wheat, he added, had been traced back to Punjab and Haryana. Blood, urine and hair samples from patients showed Selenium levels that were 35 to 150 times above normal. “We also found lower Zinc levels in their bodies.”

But ICMR scientists, while acknowledging some samples showed high Selenium content, were unconvinced.

“Apart from hair loss, these patients did not have any common symptoms,” a senior researcher from the team told ThePrint. “Their hair also started growing back within weeks.”

To date, villagers still don’t know what triggered the outbreak. Samples were collected and analysed, but no team has returned since. Independent researchers, too, have come and gone—offering no conclusive answers.

“We have not come to a definitive conclusion yet. But we will be sending our findings to the Maharashtra state administration soon,” a senior district official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said.

Also read: How India’s seniors are fighting loneliness—Love, loss, and logins

Life after hair loss: Fear, stigma in Buldhana villages

The nightmare didn’t end with hair loss. Now, with newer symptoms emerging and the original cause still unknown, villagers in Bondgaon have adopted a strategy: silence.

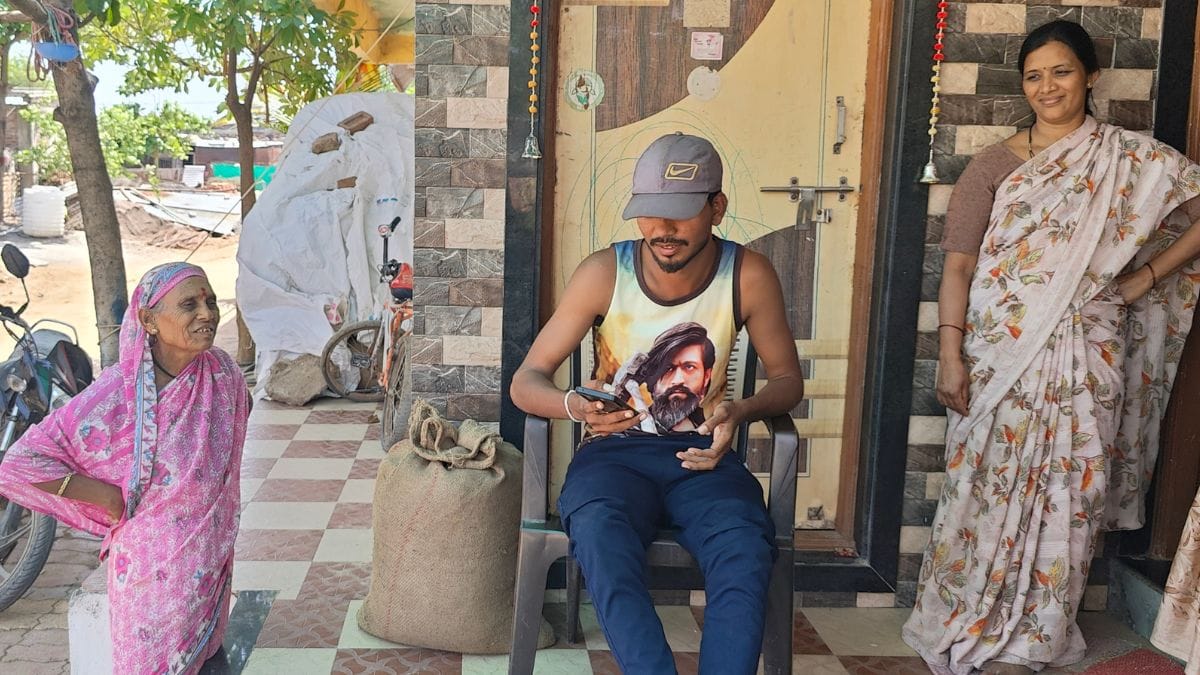

“We don’t want another round of ostracisation,” said 23-year-old Adarsh Andurkar.

He remembers how three weddings were called off as news about his village spread. Barbers in nearby villages refused to serve Bondgaon residents, fearing transmission. The village became the punchline of cruel jokes. One Marathi newspaper even published a poem titled ‘Bali-Balya’—mocking the bald women of Bondgaon and warning bachelors from nearby towns against marrying them.

“For months, we were treated like untouchables. Even now, when outsiders visit, they refuse to eat, drink or touch anything here,” Adarsh said.

In a quiet protest, Adarsh and 11 other men—none of whom had been affected—shaved off their heads in solidarity with the patients.

But the tag of the “bald village” still clings.

“People say ‘hair isn’t everything,’ but that’s not true,” Adarsh said. “Look at Hindu mythology—Lord Shiva created Veer Bhadra and Bhadra Kali from his locks. Goddesses like Durga, Saraswati, and Kali are always shown with flowing hair. Hair is a symbol of power.”

For Buldhana, that power is still missing. And so are answers.

(Edited by Prashant)