Khairthal (Rajasthan): Phones ring, papers shuffle, and villagers queue up with their files in the district magistrate’s office of Khairthal-Tijara. But instead of the hum of authority and air conditioning, the air is thick with the smell of wheat. On a Wednesday morning, as the DM tried to leave around 10 am, his car was blocked for several minutes by a blue tractor piled high with grain sacks.

This so-called district headquarters sits right in the middle of one of Rajasthan’s largest grain mandis. The building, originally made for agri officials, is supposed to be a hub of governance, but it feels more like a dressed-up barn. And Khairthal-Tijara isn’t the only district facing such issues.

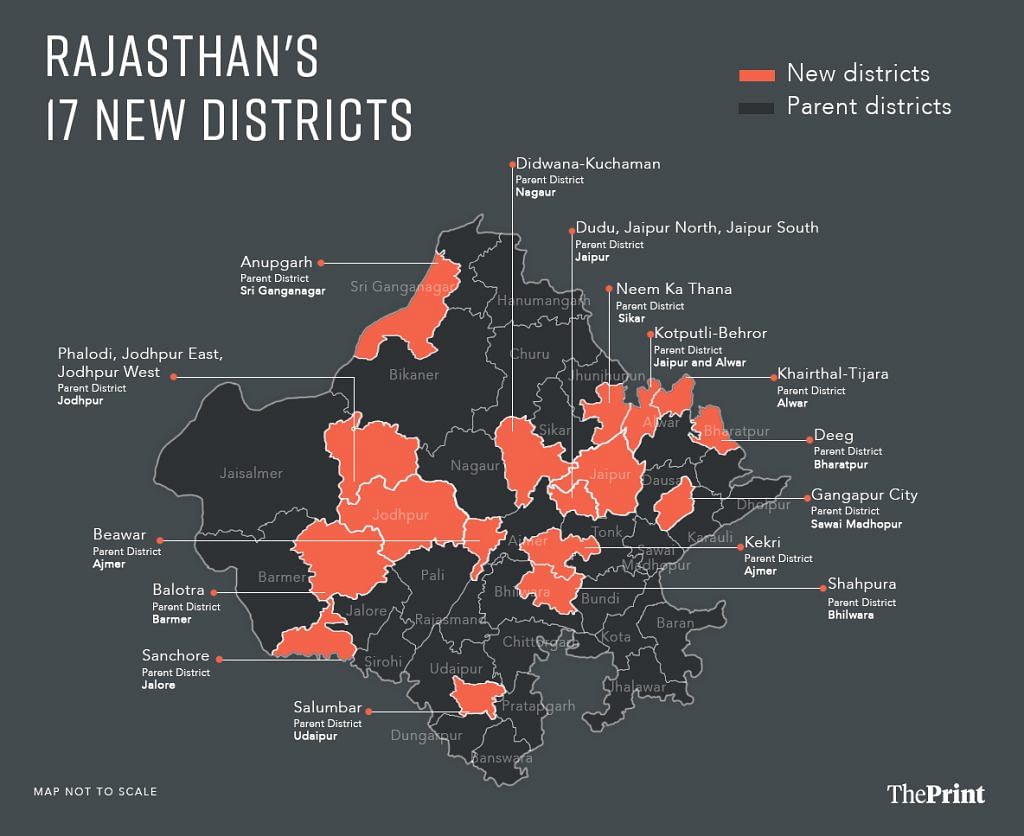

It’s been a year since Rajasthan’s former Ashok Gehlot government carved out 17 new districts, promising better governance that’s closer to the people. But today, these districts, which cost thousands of crores to create, are barely more than names on a map. They’re still running out of makeshift offices—grain mandis, hostels, old police stations, even schools. Crucial services are crippled by staff shortages, missing infrastructure, and a dependence on ‘parent’ districts. In many cases, land hasn’t even been allocated for public buildings.

What was supposed to be a grand step toward decentralisation has turned into a logistical mess and political controversy. Villagers in these ‘new’ districts still travel back to their original ones for basics like land records or driver’s licences. While politicians point fingers, life remains stuck—like the DM waiting for that tractor to move.

When the BJP came to power late last year, they quickly appointed a five-member cabinet sub-committee to review the new districts. To aid this process, a high-level expert committee, headed by retired IAS officer Lalit K Panwar, was also appointed.

The Panwar Committee submitted its report on August 30, but weeks later, no action has been taken. Instead, the issue has become a political tug-of-war between the BJP and Congress, with debates over how quickly the districts were created and whether they’re even viable.

If we still have to go to Alwar for everything, why did they even create this district? It’s become a headache for us

-Ashwini Kumar , resident of Tijara

In Khairthal-Tijara, which was carved out of Alwar, the situation is dire. Most of the staff at the DM and SP offices are on deputation from Alwar.

“Incompetent and untrained staff were sent to us. Working with them is one of our biggest challenges. We’re operating at 40-60 per cent of the required manpower for posts like constables and head constables,” said Manish Kumar, Superintendent of Police (SP) of Khairthal.

The Lok Sabha elections, he recalled, were a nightmare with the lack of trained staff and resources.

“Gaadi aur aadmi se hi police chalti hai (Police works only with vehicles and men),” said Kumar, pointing to the shortage of both. In this brand-new district, he is making do with a rented, crumbling private building as his temporary headquarters, complete with cobwebs clinging to the walls.

While the Panwar Committee’s recommendations remain confidential, official sources indicate it suggests reverting four to five districts to their original status. But the Bhajan Lal Sharma government has delayed making any decisions. The administrative boundaries are sealed pending the census.

“I have briefed the cabinet that no decisions can be made without the approval of the Census Commissioner,” Panwar told ThePrint. “This is a legal aspect.”

After Panwar submitted his report, the cabinet sub-committee held two meetings—one on 2 September and another on 18 September. However, no decision has yet been made regarding the future of the new districts.

However, in a letter dated 4 September, of which ThePrint has a copy, Chief Minister Bhajan Lal Sharma asked Home Minister Amit Shah to lift these restrictions by 31 December, allowing Rajasthan to adjust district boundaries.

“New districts are functioning with basic facilities, but no decision has been made on their future or on establishing new headquarters and public buildings,” said a cabinet sub-committee member, requesting anonymity.

“Once it’s decided how many districts will remain, the budget for infrastructure will be allocated.”

The total cost for Rajasthan’s grand district-creation project ballooned to around Rs 20,000 crore, according to retired IAS officer Lalit Panwar.

‘Half–cooked districts’

On a rainy day last week, shopkeeper Ashwini Kumar made the 27-kilometre trip from Tijara to Khairthal, hoping to sort out his paperwork at the regional transport office (RTO). It was his first time visiting the new district headquarters, but he was out of luck.

When he stepped into the DM office, an official directed him back to the RTO in Alwar as work was still being handled there

“If we still have to go to Alwar for everything, why did they even create this district? It’s become a headache for us,” Kumar fumed, black umbrella in hand.

Out of 52 government departments, only 17 are active in Khairthal, and even those are barely functioning. Transport, Excise, Mining, Labour, and the District Court still operate out of Alwar. The few existing departments are short on staff, computers, furniture, even printers. Even the Zila Parishad (district council) has not been formed in the last one year.

It’s not easy for officials, either. Three departments—Public Relations, Statistics, and Education—are crammed into a small second-floor room in the DM office. Atar Singh, who joined as public relations officer (PRO) last August, went from having his own office in Jaipur to squeezing into a tiny space with just one chair and table allocated to him.

“We’ve had to start everything from scratch here,” Singh said, shifting his backpack off the table to make space. “There’s no precedent, no example to follow. Every step is becoming a new example for the future.”

Announced just before the 2023 state assembly elections, the creation of 17 new districts—including Anupgarh, Balotra, Beawar, Deeg, Didwana-Kuchaman, Dudu, Gangapur City, Kekri, Kotputli-Behror, Khairthal-Tijara, Neem Ka Thana, Phalodi, Salumbar, Sanchore, and Shahpura—brought Rajasthan’s total to 50. Jaipur was also split into North and South districts, while Jodhpur was divided into East and West. Finally, three new divisions were also formed—Banswara, Pali, and Sikar. These changes impacted around 3 crore people.

It is possible that all the claims for creating districts were correct—but creating them all at once? Could they have been phased? We worked on these questions and mentioned them in the report

-Lalit Panwar, retired IAS officer

The goal was to improve governance, enhance services, and meet popular demand, but the reality is very different.

“All the new districts are half-cooked. They cannot be called full districts,” said SP Manish Kumar. The Collector and SP offices—necessary for district administration—were set up early on with skeleton crews, but it’s just enough to claim they exist.

“Till now, no work has been done on long-term needs, which is required for building a district,” he added. “It’s not like anyone can ring a bell and things change overnight.”

With no district court in Khairthal, the police must travel 50 km to Alwar to file case documents. Revenue records are a mess, too. In many cases, documents haven’t been fully transferred to the new districts. Surendra Singh Yadav, ADM of Khairthal, recalled a land hearing two months ago where he had to request files from Alwar.

“In such situations, hearings get delayed,” Yadav said.

Earlier this month, Rajasthan BJP president Madan Rathore caused a stir when he announced plans to scrap six or seven new districts, alleging they were created to “appease” Congress MLAs.

Costly chaos

Setting up a new district is a costly affair. On average, it costs anywhere between Rs 500-1,500 crore to establish a district. Multiply that across 17 districts and three divisions and the total cost for Rajasthan’s grand project ballooned to around Rs 20,000 crore, said retired IAS officer Lalit Panwar, who chaired the government’s review of these new districts.

The question now: was it worth it?

“It is possible that all the claims for creating districts were correct—but creating them all at once? Could they have been phased? We worked on these questions and mentioned them in the report,” Panwar said.

Tasked with reviewing districts on four key parameters—jurisdiction, viability, administrative convenience, and infrastructure feasibility—Panwar added six more criteria, including cultural identity and population.

He visited 14 of the 17 new districts, skipping Neem Ka Thana, Salumbar, and Deeg due to lack of infrastructure. In Anupgarh, he stayed in a BSF officer’s mess; in Shahpura, a heritage hotel.

“People’s emotions are very much attached to this issue,” said Panwar. “My approach was to study the national benchmark regarding districts.”

On average, a district in India spans 4,242 sq km with a population of 27 lakhs, comprising around seven tehsils, nine blocks, and 800 villages. But in Rajasthan, the average district is over twice the size—about 10,000 sq km.

There has been a demand for new districts here for a long time, which is really needed. But these districts were created in a hurry, without any preparation, due to vote bank politics

-Satish Agrawal, Udaipur-based professor of political science

Population density also varies wildly. In desert districts like Jaisalmer and Barmer, the population density ranges from 10 to 45 people per sq km, while in Dholpur and Bharatpur, it’s as high as 273, Panwar said.

However, the Gehlot government’s ambitious move to improve governance accessibility has largely led to administrative chaos.

For instance, in Sanchore, carved out from Jalore, the DM’s office operates out of an old PWD building, while the SP works from a run-down police station. Residents have to go to Jalore for mining, district council, and excise matters.

Healthcare is equally grim. Sanchore’s Chief Medical and Health Officer (CMHO), BL Bishnoi, works out of a single room in a local dharamshala. Of 39 sanctioned medical posts here, only three have been filled in the past year.

“Geographically this district is very big and its distance from Jalore is up to 200 km,” said Bishnoi. “But we’re still depending on Jalore for most medical facilities.”

Frequent bureaucratic reshuffles since the Bhajan Lal Sharma-led BJP government came to power last year have only added to the instability. In Shahpura, carved from Bhilwara, the SP and Collector have changed three times in just one year.

“It is better to keep officers for a long time to bring stability in a new district,” said a former DM of Shahpura. “Due to frequent transfers, the pace of development in the new district slows down.”

It’s not just the personnel issues. Key financial resources are also tied up. The new districts still don’t have control over the District Mineral Fund (DMFT), a critical revenue source, pointed out the ex-Shahpura DM. The parent districts continue to collect those funds, leaving their offshoots strapped for cash.

The creation of Salumbar district has stirred excitement in neighbouring villages like Aspur, Sanwala, and Kanor, which are lobbying to be included within it for better access to government services.

‘Appeasement’ vs administration

District creation in Rajasthan isn’t just an administrative matter—it’s also political.

Earlier this month, the newly appointed Rajasthan BJP president Madan Rathore caused a stir when he announced plans to scrap six or seven new districts, alleging they were created to “appease” Congress MLAs.

The backlash was immediate—reportedly even within his party—and Rathore soon retracted his claim. But the BJP government remains silent on the future of these new districts.

Over the last decade, three high-level committees have addressed district creation. In 2014, during Vasundhara Raje’s tenure, a committee led by retired IAS officer Parmesh Chandra took four years to submit its report, which the Gehlot government later rejected. In 2022, the Gehlot administration formed another committee, chaired by IAS officer Ram Lubhaya, which led to the announcement of 17 new districts and three divisions in March 2023. Finally, the Panwar committee was set up in June 2024.

Gehlot, meanwhile, defended the move in a post on X, pointing out Rajasthan’s size as India’s largest state by area and comparing it to smaller states like Madhya Pradesh, which has 55 districts. He stressed that the new districts would “improve administrative capacity and service delivery”.

Earlier a visit to the collectorate in Udaipur would have meant losing the entire day but now people have easy accessibility

-Jasmeet Singh Sandhu, Salumbar DM

But this wave of district creation was also linked with political pressure.

Several ministers and MLAs lobbied hard for new districts in their regions. In 2022, then MLA Madan Prajapat walked barefoot to demand that Balotra be separated from Barmer. Former minister Rajendra Yadav threatened to resign if Kotputli wasn’t declared a district. Similarly, Suresh Modi pushed for Neem Ka Thana, Rajendra Gudha for Udaipurwati, Alok Beniwal for Shahpura, and Babulal Nagar for Dudu.

Some political analysts say Gehlot’s decision was largely driven by the need to pacify these MLAs and ministers.

“There has been a demand for new districts here for a long time, which is really needed. But these districts were created in a hurry, without any preparation, due to vote bank politics,” said Satish Agrawal, professor of political science at Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur.

Agrawal noted that while creating new districts isn’t necessarily a bad thing, local leaders often push for them to bolster their influence.

“There are some districts, especially, on which there is a question mark. Dudu is one of them,” he said.

Carved out of Jaipur, this district has often raised questions due to its small size.

“A district with only three tehsils does not meet any parameter. If it has to be a district, it needs to be made viable,” Panwar said.

As of now, Dudu has neither a district collector nor an SP and the Jaipur DM is holding additional charge of it, said Suresh Kumar Naval, Jaipur ADM,.

Pyrrhic victory?

For four decades, Salumbar, a tribal-dominated area in Udaipur, fought for district status. When it was finally announced in March 2023, residents celebrated with processions and fireworks. But a year later, frustration has set in.

“We had demanded a district for the development of Salumbar but not much has changed here in a year,” said Dharmendra Sharma, councillor from Salumbar. “Employment, education, transport, and medical facilities are the same. Still people are dependent on Udaipur.”

Despite being only 75 km away from Udaipur, Salumbar is isolated—hemmed in by dense forests, mountains, and rivers like the Jhamri and Som. Policing is difficult, and cybercrime is rampant.

The new policing and administrative facilities, however, leave a lot to be desired. The DM and SP operate out of a former tribal student hostel. The treasury department has just two officials to manage the entire district’s finances, and basic infrastructure, like water coolers, AC, and parking, is still missing.

Records had to be hauled in from Udaipur by a team of only two or three people.

“Work that should have taken days, went on for weeks,” said a treasury official, sitting in his hostel-room-turned office.

Nevertheless, the creation of the district has stirred excitement in neighbouring villages like Aspur, Sanwala, and Kanor, which are lobbying to be included within Salumbar for better access to government services.

“The formation of the new district has raised hopes,” said Girdari Soni, a resident of Kanor.

Salumbar’s DM, Jasmeet Singh Sandhu, is optimistic too, arguing that infrastructure gaps are a separate issue from access to the administration.

“Earlier a visit to the collectorate in Udaipur would have meant losing the entire day but now people have easy accessibility,” Sandhu said. Outside his office, a sign reads: Milne ka samay: karyalaya samay me kabhi bhi (Meeting timings: Any time during office hours).

As of now, the DM’s office doesn’t have a fence, but this doesn’t seem to be by design.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)