Jaisalmer: Sam, a male sub-adult great Indian bustard, glacially moves to the front of his cage when he senses his mother nearby. At his home in Jaisalmer district, though, he has many mothers—none with beaks, and all dressed in bright green scrubs.

His caregivers, working at the conservation breeding centre in Sam city run by the Wildlife Institute of India, provide him with food, shelter, and affection. Using forceps to mimic the shape and feel of a beak, they hand-feed him, dousing him with care as they stroke and pet him. Yet, the critically endangered largest flying bird in the world has been reduced to something of a pet—though not quite.

With fewer than 150 great Indian bustards remaining in the wild, a lot is riding on Sam’s survival. He is one of 45 ‘tame’ GIBs housed at two meticulously monitored conservation breeding centres. These birds, artificially incubated and hand-reared, are the result of a successful breeding programme involving Rajasthan’s forest department, the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). The fate of the entire species lies, quite literally, in their seldom-used wings.

“Five years ago, I wouldn’t have been optimistic. But thanks to the breeding programme, total extinction is now out of the question,” said Sutirtha Dutta, a senior scientist at the WII. The government’s campaign to save the great Indian bustard was a now-or-never effort.

Five years ago, I wouldn’t have been optimistic. But thanks to the breeding programme, total extinction is now out of the question.

Sutirtha Dutta, a senior scientist at the WII

The next step is rewilding. For Sam and the other artificially incubated GIBs, it may be too late. But their progeny could hold the key. Rewilding the next generation of chicks is a monumental challenge.

This task is fraught with hurdles. The wild population will not have the luxury of hand-feeding by a team of devoted ‘mothers’. There is no established template for rewilding bustards. Then there’s the development dream, mediated through bustard-killing power lines. And perhaps the most daunting of all is the unfortunate truth—a lanky, reticent bird teetering on the brink of extinction simply isn’t alluring enough.

The conservation centre operates like a well-oiled machine, with military precision. Yet, the ultimate success of the programme hinges on rewilding the birds.

“We’ll only succeed if we’re able to build a self-sustainable breeding population,” said Mohib Uddin, a WII scientist and senior technician at the centre in Sam city.

Breeding, conservation, and habit protection are just parts of the plan. An ardent group of bustard devotees—including scientists, GIB mitras, and entrepreneurs—are working to weave this brown-and-white bird into Rajasthan’s cultural mythology. Their goal: to convert an indifferent citizenry into diehard fans who would support saving the species.

Mothers of the bustards

For GIB mitra Radhey Shyam Bishnoi, patrolling and poaching are the twin pillars of his world. His sharp eyes scan the shrubbery until they lock onto a distant flock, discernible by their striking black-and-white plumage. He goes door to door in his village of Dholiya, spreading a simple but urgent message: the great Indian bustard must not be killed or consumed.

“I’m trying my best, but the work is endless, unlike my time and resources,” he said. “It’s a different kind of rush—being in the field, understanding each area and the threats they pose to the bird.”

My in-laws don’t know about the work I do. They think saving the GIB is hindering our village’s development. They tell me that the power lines will bring ‘vikas’

The operation, however, must remain subtle, covert. Radhey Shyam wears his bustard-saviour mantle with pride, but for his former classmate Abhishek Bishnoi, saving the bustard publicly is not an option.

“My in-laws don’t know about the work I do. They think saving the GIB is hindering our village’s development,” Abhishek said. “They tell me that the power lines will bring ‘vikas’.”

There are vagaries in the bustard-saving ecosystem. Self-appointed guardians who roam the wild are dismissive of the efforts to save caged birds, while scientists at the conservation centres breathe a sigh of relief as the ‘insurance policy’ of their breeding programmes shows returns.

At the conservation centre in Sam, each bustard’s cage contains a steel water bowl, much like those used for pet dogs. There’s round-the-clock surveillance, with CCTV cameras monitored in a war-room filled with screens—one for each of the 17 birds. On a whiteboard, their regularly updated diet plans are scrawled—plenty of protein and fibre for gut health. A few lucky ones are in for a treat: mice.

The first conservation breeding centre opened in 2018, nestled in the sand dunes of Sam. Six years later, it is home to 17 adult birds, while the rest are kept at the more expansive second centre in Ramdevra, some 160 km away.

A male sub-adult, Sam was made to mate with a wooden dummy bustard. His sperm was then inserted into a female bustard in Ramdevra, who, according to technicians, conceived on her first try.

“Now that artificial insemination has started, the population can be scaled up,” said Mohib Uddin.

There needs to be a stock population of at least 50 birds at the two centres before embarking on the mammoth task of rewilding. Next month, a rewilding aviary is set to arrive at Ramdevra. Designed to replicate real-world conditions, the aviary will push birds to forage for food, interact with other animals, develop flight muscles, and endure real-time weather conditions.

The current generation, however, can’t do it. They’re completely beholden to their human caregivers.

“These birds aren’t trained for it [rewilding],” said Mohib Uddin. “The next generation will be reared differently.”

The next generation, potentially beginning with chicks like Aarambh, will spend 3 to 6 months in the rewilding aviary before they are released into the wild.

At Ramdevra, some birds reside in temperate-controlled environments. During sandstorms, they’re moved indoors. The centres are highly sterile, requiring visitors to wash their hands and feet before entering. Even the green shutters and scrubs serve a purpose—birds associate the colour green with safety and retreat at any unfamiliar sight.

The next generation, potentially beginning with chicks like Aarambh, will spend 3 to 6 months in the rewilding aviary before they are released into the wild.

“We anticipated rewilding to happen at a much later stage,” said Sutirtha Dutta. “But the programme has been more successful than we expected, and there’s hope that they can be released [earlier].” Dutta noted that breeding programmes across the world typically register a 50 per cent survival rate. “Here, about 70 per cent have survived.”

Adapting bustards for the wild

But questions remain. This is a first-of-its-kind project, and scientists are constantly making real-time adjustments. There’s no definitive playbook to follow. Rewilding is going to be a challenge, admitted Dutta. While milestones have been achieved, including the artificial hatching of 24 chicks from 30 wild eggs in 2022 and the birth of Aarambh in October, the stakes remain incredibly high.

“All of it [every milestone] was initially a question mark. Each step has been a challenge,” Dutta said. “It’s like letting your child into the wild. You wouldn’t do it without familiarising them with the environment and the threats. We’ll monitor them and refine the process. A proportion of the population will survive. The objective is to increase this proportion.”

Though there’s no exact science, the team is guided by a loose template. The mission gathered steam after WII scientists visited Abu Dhabi to study the houbara bustard breeding programme. Thousands of endangered houbara bustards have been successfully released into the wild across several Arab nations, offering valuable insights for the GIB initiative.

However, human intervention has created a bird that shares physical traits with its wild counterpart but differs quite significantly in behaviour. In the wild, GIBs steer clear of humans. At the centres, the technicians are their lifelines.

Still, these birds aren’t “as tame as they appear,” according to Mohib Uddin. When an artificial snake is placed in a cage, the birds become noticeably excited.

“Certain behaviours are innate,” Dutta explained “We don’t teach them how to predate, eat, or mate.” But the rest is learned—a sort of bustard-cultural exchange. That’s why, when their progeny are released into the wild, they’ll join a GIB flock as their new surrogate mothers.

Guardians of the ‘sacred’ grasslands

Jaisalmer’s skyline has a story—power lines stretch endlessly into the horizon, windmills spin languidly, and barbed-wire towers house solar panels generating 1200 MW of energy.

All three have been in conservationists’ line of fire for the past couple of decades—ever since they realised how rapidly the great Indian bustard population was dwindling. The bustard has limited peripheral vision, which means it frequently bumps into power lines—and meets a painful end.

“It’s been six years since the captive breeding experiment began. We’ve also seen 15-20 chicks in the wild. These are good signs,” said wildlife biologist Sumit Dookia. “But habitat is shrinking every year. Where will you release them?”

The great Indian bustard thrives in grasslands, a habitat of sparse shrubbery and vast open spaces. Yet, according to experts, these landscapes have historically been dismissed as wastelands, gladly sacrificed for development projects.

“The diktat to protect forests has percolated since colonial times,” said Dutta. “Meanwhile, open natural landscapes are prioritised for development. Other than the GIB, there’s no flagship species to save grasslands.”

But for the people of Rasla and its adjoining villages, grasslands are their ‘oran’—sacred groves. And by virtue of this connection, the GIB takes on a new avatar. Saving the GIB means saving their land.

Times have changed, but our land remains. We have no problem with the GIB—it doesn’t interfere with our work. But we want to save the oran.

Dipa Ram Singh, a resident of Sawanta

“Times have changed, but our land remains. We have no problem with the GIB—it doesn’t interfere with our work. But we want to save the oran,” said Dipa Ram Singh, a resident of Sawanta, near Rasla. He admitted he wasn’t sure whether the GIB was the national or state bird.

Spanning 65 km, the oran is a sacred expanse of bare vegetation and flat terrain where farming is prohibited. Six villages, including Sawanta and Rasla, have grown around it. Residents graze their cows and goats there, confident the animals will return home. But now, the oran is dotted with power lines.

“The oran is everything to us. We’re going to save it with our own hands—we don’t even pluck a single leaf ,” said Sumer Singh Bhati, a camel farmer and GIB mitra. “These private companies are not going to bring ‘vikas’.”

For Bhati, who recalls seeing groups of 15 GIBs as a child, the bird is family—a symbol of their shared home. But he fears it will soon become “the new dinosaur,” a creature that lives large in public memory but has been reconfigured by imagination. “Children barely know about the GIB,” he lamented.

While the picture painted by local people is bleak, the government is persisting with habitat restoration. Near Pokhran lies a 200-km stretch of military land, protected by default and home to several GIB sightings. Similarly, the Desert National Park in Jaisalmer contains GIB dedicated areas with no power lines or renewable energy infrastructure, just chinkaras bounding through the landscape alongside wild pigs.

“In-situ and ex-situ conservation need to go together. They are two simultaneous strategies,” said Ashish Vyas, deputy conservator of forests. “Our enclosures are predator-free and closely monitored. They’ve become safe breeding grounds.”

Yet, according to Dookia and several GIB mitras, 80 per cent of the population resides outside protected areas.

“Where the forest department hangs up its boots, our work begins,” said Dookia, referring to the meticulous efforts of conservationists and NGOs to track the birds and safeguard their eggs. A bustard lays just one egg per year, directly on the ground—without the shelter of trees, its survival is always precarious.

Myth, memory, and a memorial

Across the road from Jaisalmer’s Degrai temple stands a towering memorial—with an imperious-looking beak. It’s the first bustard memorial, dedicated to two birds who died after colliding with power lines. The villagers raised funds to erect this imposing tribute.

“This was the first death on our oran’s high-tension line. It was a male bird in 2022,” said Bhati, gazing at the statue. “I think about him every day and want others to remember as well. It hurt me deeply.”

The memorial’s location, near the temple, is intentional. It invites people to see the GIB as a holy bird, inextricable from god and the earth.

Yet, the GIB never took to mythmaking. “It’s one of life’s strange mysteries,” said Dookia. The GIB was never part of local folklore until NGOs began manufacturing stories to inspire conservation efforts. It helped—local people realised the urgency of the situation and began saving the bird. Although, Mohib Uddin said people used to believe that eating GIB meat increased a man’s libido.

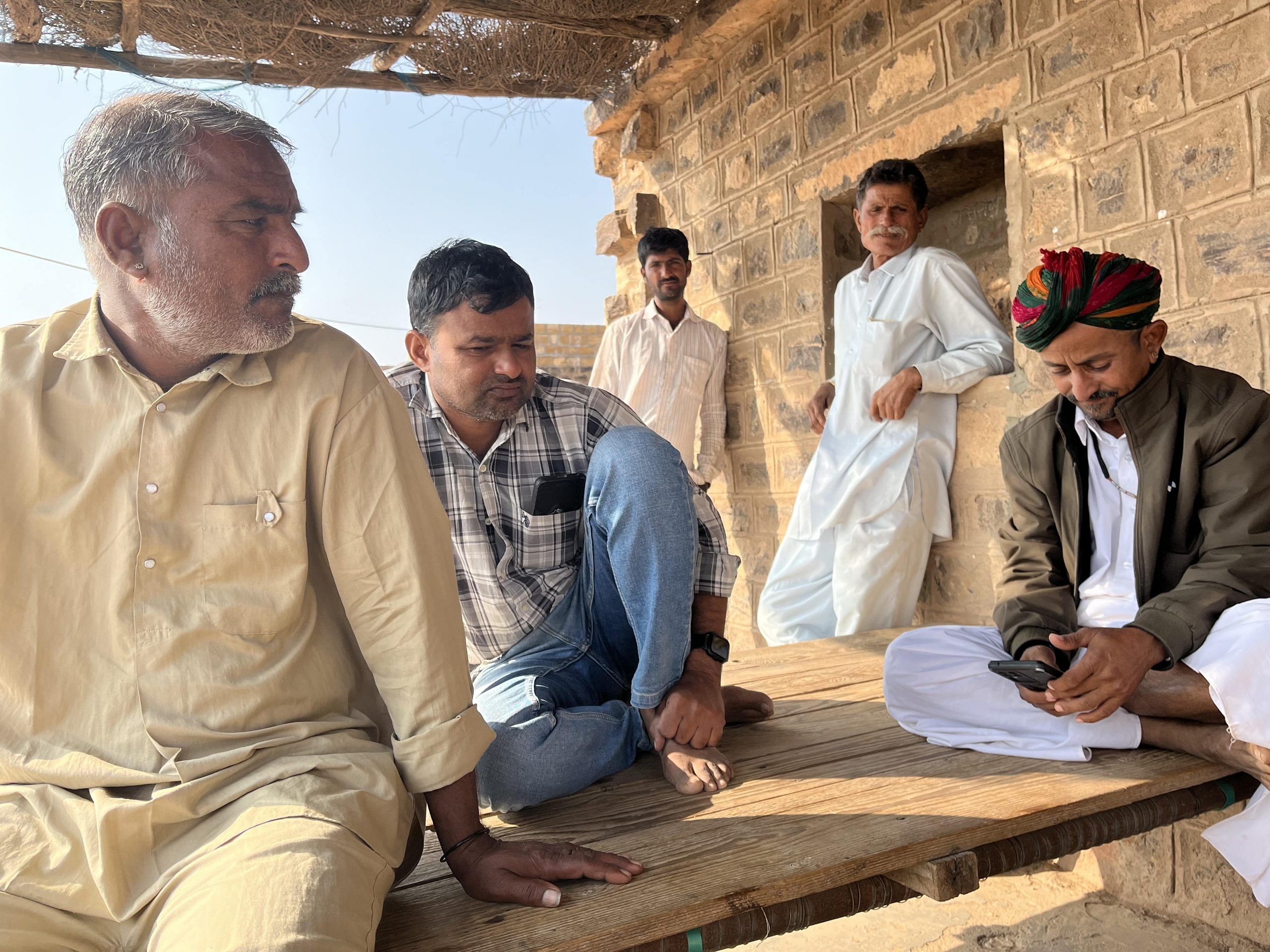

GIB mitras like Bhati and Radhey Shyam spread awareness through village chaupals and school visits about the swiftly disappearing bird and the gargantuan task to save them. In Dholia, Radhey Shyam refills the village’s watering hole, hoping to attract bustards.

“Saving the GIB is my religion—that’s the kind of peace I get from doing this kind of work,” said Radhey Shyam, reclining in the gypsy he uses to track the bird. In his village, everyone knows him as the man committed to the bird.

At Nirmal Mandir, a local school, only five out of 30 students raise their hands when asked if they had seen a GIB. But entire class nodded eagerly when asked if they’ve seen the GIB in photographs. Their school textbooks include a comprehension passage narrated by the GIB. The text describes the bird’s personality, its shy nature, and rues its decline.

“Friends! I’m upset. The government made me the state-bird. People want to pay to see me. But still, my numbers are dwindling,” the passage reads.

As the students ponder these words, Sam and Toni—named after the American author Toni Morrison—rest in their cages at the conservation centre. Insulated from the dangers of the outside world, their human parents keep vigil.

“We are the first thing they see when they open their eyes,” said Mohib Uddin. “And we feed them. Of course, they think we’re their mothers. Sometimes, when we bring their favourite food, they do happy jumps.”

As the sun sets, Sam and Toni take flight—within their shared, funnel-like cage.

(Edited by Prashant)