Mansa: A group of six men holding sticks, pistols and swords stand guard at the checkpoint at the Ralla village border in Punjab’s Mansa district. They stop cars, search bags, and frisk everyone entering the village. The men, who work in shifts through the night, are part of a self-appointed drug-monitoring Nasha Roko Committee. They’re not sniffing around for heroin, but for a red and white capsule that’s cutting a swathe across Punjab—the painkiller pregabalin.

This new ‘plague’ has galvanised vigilante groups and nasha roko committees across villages and towns.

“We have been able to reduce alcohol and chitta addiction in the village by 95 per cent. It is only this pregabalin and other medical nashe that we are fighting against now,” a committee member said.

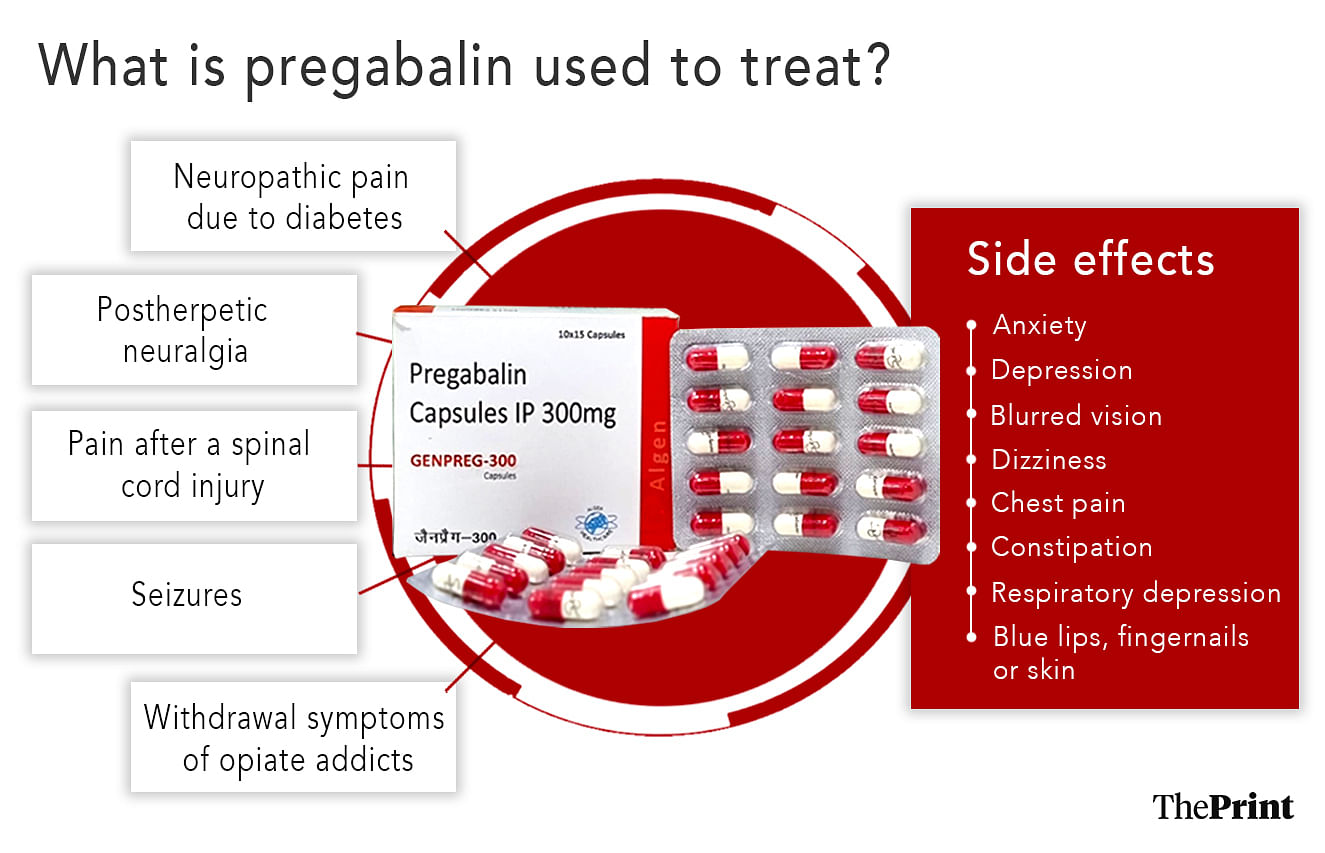

Pregabalin, a prescription drug used to manage neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and generalised anxiety disorder, is the new ketamine of Punjab. Chitta, the local name for heroin, is now old school. For the youth of Punjab, pregabalin, colloquially known as koda or by its brand name Signature, is all the rage. It’s cheap, easily available and not punishable under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act. According to the Punjab police, over 11 lakh pregabalin pills were seized across the state till August this year. It’s another chapter in the state’s war against drug abuse, which claimed 266 lives between April 2020 and April 2023.

“One capsule is enough to numb the senses completely, but they’re consuming an entire strip at once,” said Dr Jitender Aneja, psychiatrist at AIIMS Bathinda, who now sees at least five cases of pregabalin overdose in the ER every day. The drug, which is also given to opium users to wean them off, is now becoming a menace. The overuse of pregabalin can be life-threatening—it causes brain seizures and can send you into a coma.

But it was only last week that district magistrates across Punjab banned the sale and stocking of products with over 75mg of pregabalin. Until then only a few districts in Western Punjab, such as Mansa and Bathinda, had enforced such a ban. Now the police across the state are empowered to crack down on black marketeers and smugglers, and register FIRs against chemists selling the tablets without a prescription. But for families who’ve seen their children and husbands fall prey to the drug, it’s too little too late.

We have been able to reduce alcohol and chitta addiction in the village by 95 per cent. It is only this pregabalin and other medical nashe that we are fighting against now

– a nasha roko committee member

With the view that the government is not doing enough to keep a check on the drugs, Punjabi society has started forming anti-drug committees and doling out vigilante justice. At Ralla, the rural equivalent of the urban neighbourhood watch takes its role very seriously. People caught with a huge stash of the drug are given a sound beating before the police are called. Videos are recorded in case they are smugglers, and if the person is from the village, he is sent home and a watch is kept on him. They’ve registered 17 complaints with the police in seven months.

“With the ‘medical nasha’ on the rise, even children have been consuming the Signature drug. The police and government are unhelpful so we have taken up the mantle of eradicating drug abuse from our society,” said Ballot Singh, the sarpanch of the village.

Ralla’s drug monitoring committee has even bought a car to make their vigils more effective. They travel in a sky-blue Innova, bought by collecting funds from each house in the village. It has been customised with speakers and sirens on the roof, its doors are painted with anti-drug campaign posters.

“We appeal to everyone to be on the lookout for drug abusers and smugglers. Contact the anti-drug team if you find anyone, these people are a danger to society,” they announce from the speakers as they do their daily evening rounds.

Also read: Desperate Indians want Ozempic on prescription. Huge shift from traditional drugs, say doctors

Rise in popularity

After years of living under the haze of pregabalin and heroin, Laven Joga from Joga village in Mansa district is slowly and gradually getting his life back on track. Every evening, he visits his neighbour, a labourer who is a known addict. He checks the man’s belongings for capsules, while cautioning him.

“Listen to me carefully, all that you earn, you spend on drugs. Look at your children’s faces. Don’t do it again. Or I’ll have to be stricter with you,” he stares his neighbour down before walking away. Joga quit four years ago by spending two weeks at a neighbouring Gurdwara.

The constant gurbani in his ears changed him, he said. “Pregabalin is now popular, but it has been abused here in Punjab for years now. It is cheap and the high is good, it takes you to another world,” he said.

Pregabalin is widely prescribed by medical practitioners for orthopaedic and neurological treatment in dosages up to 150 mg. But today, the drug has found itself entrenched in Punjab’s black market in dosages of 300 mg and even 400 mg, which are used for veterinary purposes. An entire strip of 300 mg can be procured for anywhere between Rs 150-400.

In the last year, the police seized tablets worth Rs 3 crore and the drug department has made seizures of up to Rs 5 crore, said a senior police official who didn’t wish to be named.

The police and government are unhelpful so we have taken up the mantle of eradicating drug abuse from our society

– Ballot Singh, sarpanch of Ralla village

Pregabalin became popular during the pandemic when the production and sale of opiates, heroin and other drugs were affected by the constant lockdowns. First taken by opioid users, now the drug is becoming popular among school and college-going students.

The fact that consumption is not punishable under the stringent Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985 or under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940, which regulates the import, manufacture and sale of certain substances, has led to the mushrooming of its use.

For the anti-drug task force, pregabalin has now been categorised as a ‘drug of concern’, said a police officer. Most districts of Punjab including Mansa, Bathinda, Gurdaspur, Tarn Taran and Amritsar banned the sale and usage of drugs by orders of the district magistrate, some as recently as last week. But it is not enough, users and sellers are booked only under Section 223 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, which concerns obedience to orders given by public servants.

“We have been renewing prohibitory orders for a while but unfortunately that has not been able to prevent the usage of pregabalin. The punishment of violating orders is very light,” said a district magistrate of a western Punjab district.

The accused can secure bail immediately. (Under the Indian Penal Code, it came under Section 188.)

Last year, the Punjab police wrote to the central government to put Pregabalin in the H and H1 schedule of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, to ensure that over-the-counter sale of the drug without a prescription can be prohibited.

“Registering cases under these sections is a headache for the police. It does not deter the users. We have registered more than 500 cases since January but it is useless,” said Manmohan Singh Aulakh, Superintendent of Police (deputy) Mansa.

Also read: A Delhi doctor is the ‘Tihar specialist’. Extracts phones, drugs & blades from inmates’ bodies

Vigilante justice

At nearly six feet, the burly Seera Dhillon cuts an imposing figure as he rumbles down the street of Joga village in his run-down Pulsar. The men stand aside, bow their heads and raise their hands to the forehead, offering a respectful salute.

His “relentless fight” against the drug mafia has earned him respect and goodwill. That the 30-year-old is an associate of Amritpal Singh and faces charges of sedition is irrelevant to villagers. He is their local hero.

“Nobody is willing to take responsibility. Someone must be responsible, the cops, the MLA, or the Chief Minister himself,” said Dhillon.

This lack of faith in the police and the government to fight the drug problem has made vigilantes like Dhillon influencers and celebrities.

“Seera has put a stop to drug abuse in our village in a way that the police haven’t been able to in years. Whenever Seera is out on his bike, the smugglers shiver and their legs tremble. He is our hero,” said a villager who did not want to be named. Dhillon has close to 80,000 followers on Instagram, where he posts videos of smugglers, ‘exposing’ them for selling drugs. On 6 September, he posted a video of another vigilante, ‘Baba Gora’ from Sardulgarh Mansa, who claims to have ‘seized’ 250 strips of Signature capsules from a roadside vendor.

“These guys are selling drugs in the form of capsules to 8-10-year-old girls. Even your daughters aren’t safe,” Gora Baba can be heard saying in the video. He is part of Dhillon’s network of nasha roko committees spread across the state.

“We are alerting the administration. We won’t hold back once we have them. We won’t think twice before breaking their knees or legs,” he said. The reel has been shared more than 350 times and has 95,000 views. “The government should do the work of stopping drugs, but ordinary people are doing it, they are trying to save the future of Punjab,” a top comment reads.

While they acknowledge the pregabalin problem, the police are unimpressed by such rhetoric. “It’s a front for collecting hafta (cut money),” said Manmohan Singh Aulakh, the SDP of Mansa.

Other countries like the United States, too, are waking up to the abuse of pregabalin, which has slipped under the radar, because of its calming effect, sometimes described as a ‘gentle high’. People with a history of heroin or opioid abuse are particularly susceptible to it as it helps sustain their high.

Dhillon, Gora and his vast network of vigilantes have the support of parents who are worried about their children. Their methods—from public shaming to beatings—have the local stamp of approval.

“Our group catches four to five people like this every week. it has completely destroyed our society,” Gora told ThePrint. The vigilantes have now banned the sale of the popular, bright red energy drink, Sting. Kirana stores have been given strict instructions, in consultation with the village panchayat.

“The drug is mixed in the drink and served to kids [by peddlers] to get them addicted to it. We are against the sale of Sting in our village now,” Gora Baba said. Even Ralla village’s sarpanch has now directed kirana stores to stop selling Sting.

I constantly receive threats on the phone. Some very powerful people are involved in this scam, and I am fighting with my life at stake for the children of Punjab

-Parminder Singh ‘Jhotha’, Mansa’s vigilante hero

Back in Mansa city, men—some as young as 18—sit in clusters on a vacant plot next to a flowing drain. They stare into nothing. They don’t react to any stimulus. They don’t talk when approached, or run away or defend themselves when somebody physically abuses them. This place near the railway station is the local drug addicts’ ‘den’. There are as many as 12 pharmacies in the vicinity, and local residents are convinced that they supply Signature and other medicines abused by the youth.

Parminder Singh ‘Jhotha’, a state-level boxer, is Mansa’s vigilante hero. He has taken it upon himself to shut these shops and nab people selling pregabalin illegally. Last year, he beat a medical shop owner to a pulp and paraded him with a garland of shoes tied around his neck. When he was jailed, Mansa’s residents took to the streets to protest his arrest.

“I constantly receive threats on the phone. Some very powerful people are involved in this scam, and I am fighting with my life at stake for the children of Punjab,” said Jhotha, while sipping a cup of tea at a gym he manages.

A government doctor who did not want to be named made a similar allegation when they attempted to bring the abuse to the notice of the authorities.

“I was told to never complain about pregabalin by a drug inspector I met. He told me very powerful people are involved and that my life could be in danger,” said the doctor.

“There’s a Signature addict in every gully of the city, in every village, in every college of the state, it has completely taken over Punjab,” Jhotha claimed.

Also read: Punjab’s Canada visa obsession is wilting. Study abroad & travel shops running near empty

Lives at stake

When Kuldeep Singh 30 runs out of money and pregabalin, he leaves the vacant plot to return home to his wife, two sons (eight and 10 years old), and his father. But their wellbeing isn’t his top priority. His next fix is.

He comes home, beats his wife and asks for money to be able to procure the drug. He grabs her by her hair and tells his father he will kill her if he doesn’t get Rs 400. When that doesn’t work, he steals things from his house. In the last year, he has stolen and sold a television set, mixer grinder, sewing machine, his kids’ school books and cycles —all to fund his drug addiction.

“He cannot buy chitta, it is very expensive. So he buys Tramadol or Signature, whatever he can find, and consumes the entire strip in just one day,” said his wife, Sarabjeet Kaur. The stay-at-home mother is in her late 20s and runs the household with her father-in-law’s income.

When he’s high on Signature, Kuldeep is unable to move. Even if he is served food, he falls face down on his plate and passes out.

“He’ll drown in the katori (bowl) of pulses I serve him one day. I hate that my children have to see all of this,” Kaur said.

Kuldeep refused to talk about his addiction. “Please leave me and my family alone,” he said.

The psychiatry wing of AIIMS Bathinda has 10 beds reserved for patients who have substance use disorder. Almost half of these are now occupied by pregabalin addicts. They come to the ER in a near-comatose state after having epileptic attacks. Some are admitted in view of withdrawal symptoms that include anxiety and panic attacks, aches and pains, and sleep disturbance. The addiction has led to deaths, said psychiatrist Dr Jitender Aneja, but he has yet to officially determine a mortality rate.

Patients come from districts like Fazilka, Mansa, Bathinda, Mukhtar Sahib as well as neighbouring states of Rajasthan and Haryana. Most are in the age range of 18-30 years, a majority of them labourers, though the addiction cuts across class, according to Aneja.

He is currently conducting a study on people who abuse pregabalin, with a sample size of 1,000 people, of which 17 are women. All male addicts are former opium abusers, while the women are not.

“Pregabalin is often used by drug addicts, especially those abusing opium, to counter withdrawal symptoms of opium. However, there are no specific medicines with us to manage the withdrawal symptoms of pregabalin. So giving up Pregabalin is extremely difficult for the patient,” Aneja told ThePrint.

He claimed his ‘fight’ against the drug has invited backlash from the medical community who see the drug as important. In other cases, reporting medical shops to drug inspectors has resulted in threats to Aneja.

Back at the Singh household, Kaur admitted that she prefers her husband in a drugged state. “At least then it’s all quiet, he doesn’t hit me,” she said. But then she quickly corrects herself.

“Other than the domestic abuse and drug addiction, he is a decent man.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

I am an orthopedic resident doing pg at SGRD hospital , and I know the ground reality of this menace but methylcobal plus pregaba are one the most common combination / single dose prescribed by us orthopedicians for Lower back ache and cervical .Completely banning the drug is out of question since it is common prescription for about half Indian population specially punjabis

A list of all drug addicts in Punjab must be prepared. The Indian govt should assist them in obtaining Canadian visas.

This way India gets rid of the problem. And Mr. Justin Trudeau gets to increase his committed votebank.

A win-win situation for both.