New Delhi: Growing up in UP’s Fatehpur Sikri, 26-year-old Ganga Prasad dreamed of serving in the Indian Army. But when he aged out of the eligibility window, his hopes of donning the green uniform were dashed. So, he chose the next best option—a blue uniform branded with the SIS Security logo. Though he couldn’t guard India’s borders, protecting its neighbourhoods night and day seemed good enough.

This wasn’t unchartered territory for Prasad. He had relatives working as security guards in Delhi and Gurugram. The monthly pay of around Rs 20,000 was decent, and with his sisters approaching marriageable age, stability was important. So, when the company Security and Intelligence Services (SIS) held a recruitment drive in his block, he readily applied.

Prasad is now training to join a growing brigade of young Indians trading military or government ambitions for a steady paycheck. They patrol the frontiers of urban India—towering condos, corporate headquarters, sprawling malls—both ever-present and unseen.

For these men, a job with one of the big security agencies isn’t aspirational, but it’s better than the available alternatives as delivery men or drivers.

“I would take this job over working for Swiggy and Zomato any day. But my future plans are saving money and starting a business with my brother back in my village,” said a guard working at an ICICI Bank in central Delhi.

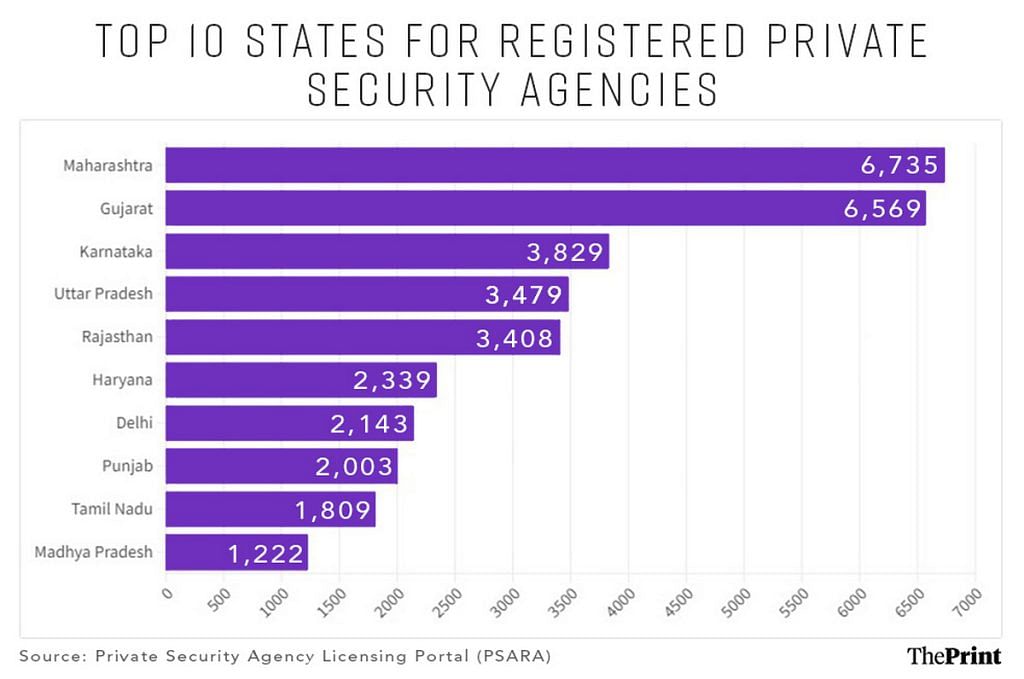

The private security industry is one of the biggest job generators in India, with over 23,000 registered private security agencies in India, according to the government’s Private Security Agency Licensing Portal (PSARA).

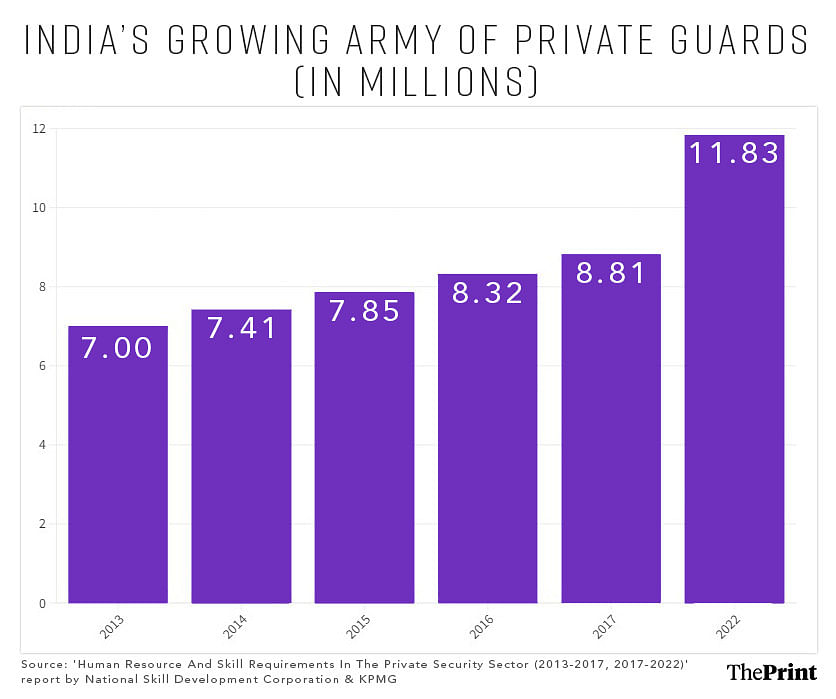

The sector employed about 7 million people in 2013, according to a National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC)-KPMG report, but the numbers are now estimated to have crossed 12 million. The market size was a projected Rs 1.5 lakh crore in 2022, with the organised sector of the industry growing at some 20 percent each year. This organised sector comprises only 20 percent of the market, but contributes 80 percent of the revenue.

The job of a security guard is not one of carrying a stick and sitting by a door. It is a skilled job. That is why I opened training schools

-Ravindra Kishore Sinha, founder of SIS

“Security is turning out to be one of the most important sectors for facilitating the transition from farm to non-farm jobs. It is one of the fastest growing segments in the job market,” said Manish Sabharwal, founder of TeamLease, a recruitment platform. “China’s transition from farm to non-farm employment occurred in factories. India’s transition is happening in customer service, sales, logistics, and security.”

Demand for private guards is booming, driven by growing tier-1 and tier-2 cities, offices, gated communities, and a low police-to-population ratio. Most of the supply of guards comes from states like Odisha, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Jharkhand, with most large agencies maintaining branches in these regions.

But Sabharwal says that the growing security industry is also, in a sense, “symptomatic of state failure”. If citizens were provided with adequate safety, so many guards wouldn’t be needed.

It is symptomatic of the Great Indian Middle-Class Exit—where the well-heeled insulate themselves from state incapacity through private water, education, healthcare, and security. In the country’s myriad “gated republics”, small armies of private guards are the sentinels.

It’s also not a particularly attractive career path for young people, offering little prestige, growth, or perks.

Even Prasad isn’t looking at the job of a guard as his end goal—he plans to prepare for a police constable post.

The NSDC-KPMG report describes security guard jobs as “a last resort” for urban individuals and a stopgap for rural workers during “poor agricultural seasons”.

The sector’s potential for employment generation isn’t widely discussed in the media either, which Sabharwal attributes to what the need for guards implies about government-provided security.

The last major discussion about security guards in the public domain was ahead of the 2019 general elections, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi called himself the country’s chowkidar, or watchman, and Rahul Gandhi countered with “chowkidar chor hai”. Modi then mobilised 25 lakh security guards online and spoke to them about Gandhi’s comments and the importance of their profession.

But the dignity and status of guards are always in question—even those guarding formidable gates with the power to turn people away. Last year, a viral video showed a Noida woman berating a guard over a parking issue, yelling “andha hai kya (are you blind)?” In another Noida incident in 2022, a lawyer abused and attacked a guard, pejoratively calling him a “Bihari”.

Also Read: Blinkit deliverymen would rather work for Uber-Ola, run YouTube channels. Dignity comes first

Not an unskilled job

At least one aspect of Ganga Prasad’s Army aspirations is coming to life—military-style training. Every day, he grits his teeth through a routine of pull-ups, army crawls, and rope climbs. He’s also mastering crisp salutes and standing ramrod straight until dismissed.

Prasad is enrolled in a three-week residential boot camp at the training academy of SIS in Delhi’s Najafgarh. Only once he completes it successfully will he be deputed for a security guard job. He pays a fee of Rs 8,000 to the school, while SIS claim to invest Rs 10,000 in training each security guard.

SIS, founded by former Rajya Sabha MP Ravindra Kishore Sinha in 1974, has 22 such schools. Sinha, then a journalist, started the security agency in Jharkhand after reading about retired soldiers struggling to find jobs.

Today, SIS employs nearly 3 lakh people, 95 per cent of them security guards, making it one of the largest employers in the country. It claims to have a revenue of over Rs 11,000 crore and 374 branches.

It is no longer just providing jobs to retired personnel from the forces, but still borrows heavily from the structure and culture of the military. About 10,000 young men are trained at its schools every year and only then sent for postings across the country.

One madam somehow does not get her Amazon delivery, and we can be out of a job

-security guard at a Gurugram housing complex

“The job of a security guard is not one of carrying a stick and sitting by a door. It is a skilled job. That is why I opened training schools,” Sinha told ThePrint at his sprawling red bungalow in Sunder Nagar, a leafy neighbourhood in Lutyens’ Delhi.

SIS guards must be at least 5 ft 7 inches tall and new recruits have an age cap of 35 years. They receive various job benefits, including Provident Fund and insurance.

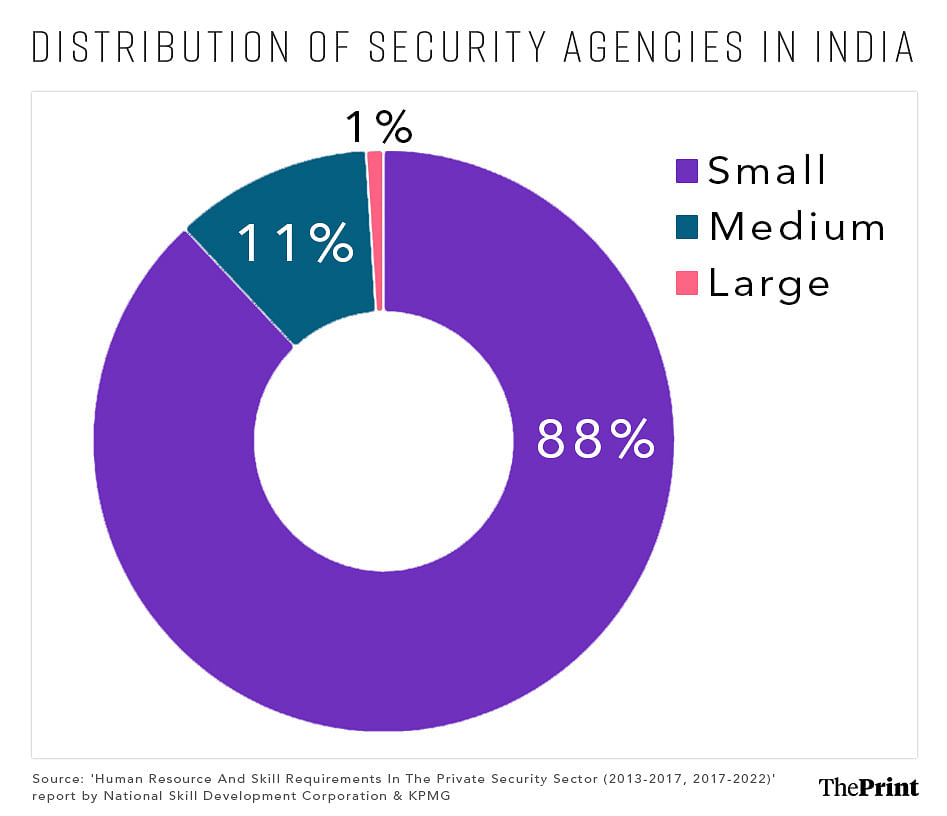

While organised companies like SIS must abide by the Private Securities Agencies (Regulations) Act 2005 and other laws like the Payment of Wages Act 1936, they only comprise a sliver of India’s private security sector, which is dominated by small players.

In the vast unorganised sector, perks are few and guards often endure lower wages, longer hours, and no leaves. The agencies that place them also pocket a portion of their salaries, usually in the range of 10-15 per cent.

Organised companies like SIS take a cut as well, but it’s structured differently.

“We charge 15 per cent of a guard’s monthly salary as our cut, but it’s part of the contract we sign with our clients,” Sinha said. “It doesn’t come from the guards’ pay.”

SIS also offers a paid graduate training programme modelled after the Indian civil services for managerial positions, complete with terminology like “cadres” and “batches”. After completing training, they are guaranteed a job in zonal, regional, or branch operations and can rise through the ranks, from roles like assignment manager to branch head, then even vice president or president.

“The management training programme for graduates is excellent and comes with job security and vertical growth,” said Aryan Bhardwaj, a 2008-batch group training officer.

Within a mere 40 minutes, a guard in a Gurugram housing complex fielded a resident’s irate call over not letting through a deliveryman fast enough and another about missing flowerpots, all while logging a steady stream of visitors on MyGate.

‘Recession-free’ & tech-proof

India’s new breed of trained guards are not just glorified watchmen but tech-savvy professionals.

Big technological changes are afoot in the security business—from drone cameras to gates manned by apps to an increasing number of CCTVs—but Sinha says guards will never go obsolete. They just have to adapt. The training provided by SIS covers not just fire safety, CPR, and security protocols, but also lessons in working with cameras, computers, and apps.

SIS has a first-mover advantage and has built necessary infrastructure over the years to conduct extensive training programmes. Smaller players don’t always have the wherewithal to do this, but many do provide monthly on-site training. As demand grows, so does the competition, with private security businesses mushrooming across cities.

Companies like G4S and SIS give salaries up to Rs 25,000. The work timings are also under 10 hours. But I am not tall, or qualified, so I’ll never be employed there

-Sharma, a security guard in Delhi

“This business does not require a lot of seed money. Since it is part of the service industry, it really depends on the entrepreneur how much money they want to invest in the business,” said Gaurav Kumar, operations manager of Crest Force, a Delhi-based medium sized agency that provides not just security guards but bouncers and personal bodyguards.

Established five years ago, Crest Force employs 500 guards across corporate offices, hospitals, and an apartment building. Their turnover has jumped from Rs 5 lakh in their first year to Rs 1.5 crore.

Kumar is confident that demand will never dry up.

“Ours is a recession free business,” he said at his two-room office. “We were the employment providers during (the Covid-19) lockdown. We also saw growth in our business in the years after the lockdown. Security is an essential service, after all.”

To keep the human capital flowing, companies like SIS and Crest Force hire people through recruitment drives in rural areas, but with different degrees of success. While Crest Force has to chase local district administrators for permissions to conduct these camps, the well-established SIS enjoys cooperation from district administration and police.

But even as security businesses grow leaps and bounds, with talk of turnover in crores, the security guards who form the backbone of the industry are dealing with struggles old and new.

Also Read: Gig dream is fading for Uber, Ola drivers. They are forming picket lines & support groups

Long years & longer days

Many security guards stumble into the profession rather than actively seeking it out. So it was with Kumar, who came from Agra to Delhi with his wife in an overcrowded bus for a fresh start 30 years ago.

In 1994, he rented a small shop in Kartar Nagar and opened a grocery store. It failed, leaving him sitting in a pile of debt and forcing him to close down. A neighbour then helped him get a job as a guard at Delhi’s Palika Bazaar, earning Rs 7,000 for a 12-hour workday. Kumar took the job, and has been wearing a shade of blue ever since.

“I felt quite empowered, especially on night duties with my stick, blowing my whistle at night, warning thieves that as long as I am here, nothing untoward can happen,” he said.

But the excitement of the job soon fizzled.

“I was earning good money then, but I could never really earn more than that,” he said.

Twenty-four years on, Kumar, now in his 50s, earns Rs 18,000 a month by pulling two shifts— first manning the gate at a huge market in central Delhi, then guarding a mansion. He works 20 hours every day.

“I haven’t slept peacefully in years,” he said.

Yet, he tries not to complain.

“Every job has its pros and cons,” he said. “You have to work hard to earn money.” He plans to retire and return to his village once his daughter gets married.

Both Kumar and his colleague at the mansion, Sharma, are employed by one of the small, unorganised agencies that monopolise the private security market. Both of them are short, ageing, underqualified, and don’t have job options lining up for them. They know they don’t stand a chance of being employed by one of the big agencies.

“Companies like G4S and SIS give salaries up to Rs 25,000. The work timings are also under 10 hours. But I am not tall, or qualified, so I’ll never be employed there,” Sharma shrugged.

Instead, Kumar and Sharma try to make the most of the sparse resources they have. They’ve built a tiny shed for themselves this year using scrap materials to shield themselves from the sun and rain. They’ve also scrounged up a discarded bed and two chairs for their station. To get through the heat, they bought a small desert cooler. Previously, they had no designated seating area.

Sharma also tends the gardens and makes evening tea for others working there. “I like tea at 5 pm, so I make it for everyone. And I’ve always enjoyed gardening; I don’t see it as extra work,” he said.

Like Kumar, Sharma is an accidental security guard. He was once a landlord in Delhi, but after demonetisation, he fell into a spiral of debt and failed businesses and had to sell everything. He took the first job he could find and now earns Rs 15,000 per month.

“I don’t think any job is big or small. All jobs are dignified. And I am happy I get to work as a guard,” Sharma said.

At a manicured Gurgaon gated complex with a poolside clubhouse and nearly 400 apartments, a weary sigh escaped a weather-beaten guard in his late 50s.

Within a mere 40 minutes, he had fielded a resident’s irate call over not letting through a deliveryman fast enough and another about missing flowerpots, all while logging a steady stream of visitors on MyGate. When packages arrived and residents weren’t home, he carefully stowed them away on a shelf.

Originally from Bihar, he earns Rs 18,000 each month and works 12-hour shifts seven days a week, not counting the long commute home by bicycle.

Last month, he claimed, the guards quickly doused a potentially devastating electric fire. They had fortunately received training in fire protocols.

“We are heroes for a day in such situations,” he said, asking not to be named. “But one madam somehow does not get her Amazon delivery, and we can be out of a job.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

nice article

Sachin rajput

I need a job security supervisor thank you

Sis me hu

G4S is UK based company . This security service should be banned in India. Even after quit India. They use our own people to loot.

Those Indian who has thought of our ancestors got killed before Indpendence never allow such services in India.

Hopefully we Indians have enough security private hands to safe guard our own Industries and other belongings.