Pimpri Chinchwad: Waste picker Vijaya Chavan never missed a court appearance for twelve years. Threats, harassment, and social discrimination didn’t deter her. She would sit in the stuffy municipal labour department room that doubled as a courtroom, face shielded behind her saree pallu to avoid intimidating glares. She was an immovable fixture in what seemed like an immovable dilemma.

And Vijaya, or Vijubai, a slight woman who wears glittering gold proudly even while working, won a formidable battle against the might of the state—by just showing up.

She attended every court hearing for twelve years to fight for her— and 310 other waste pickers’—right to receive minimum wages. And on 17 May 2024, the money finally hit their accounts: a whopping sum of Rs 7.5 crore in total, around Rs 3 lakh each.

The waste pickers, mostly women, of Pimpri Chinchwad have won a rare battle: they were awarded the money in a first-of-its-kind legal victory against the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC) and its contractors in August 2023. The win was ironic because it was secured against a municipal corporation that has been consistently feted as one of India’s wealthiest. Not only does Pimpri Chinchwad have a 5-star rating from the Swachh Bharat Mission as a Garbage Free City, it also ranks as the top municipal corporation in Maharashtra, ahead of both Pune and Mumbai, for e-governance.

But the struggle of Pimpri Chinchwad’s waste pickers has exposed the hollowness of rankings, exploitative ways of engaging labourers and bureaucratic fault lines—even within a corporation as strong as PCMC.

“Twelve years have passed, but I remember everything,” said 47-year-old Vijubai, her eyes flashing. “I remember the fear. I remember the threats. I remember the meal the contractor fed us while trying to bribe us to back down. And I’m glad we put in the effort and didn’t lose hope, because now I can remember the victory.”

This is a story of determination, dignity, and desire, pieced together through years of struggle by valiant women who are relegated to the bottom of the social pyramid.

Vijubai and women like her, born into lower caste families, have known no other life than being waste pickers, collecting trash from households and doing the literal dirty work for the rest of society. But over the last twelve years, they have forged bonds of friendship, sisterhood and comradeship along the way. They not only got their wages back, they achieved something bigger. They have created better working conditions for sanitation workers and waste pickers and segregators, reinstated the primacy of trade unions and did the unthinkable—holding power to account. And now their legal victory is creating ripples of hope for other communities, fighting for their right to dignified work with minimum wage.

“After twelve years, it’s a massive victory but it feels blunted. We had to fight for such a long time for something that is fundamentally enshrined in our Constitution. Over 30 people have died in this process,” said Aditya Vyas, general secretary of the waste pickers’ trade union Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat (KKPKP). “It was a reasonable ask. If only the authorities had been more sensible earlier.”

The PCMC, which still outsources work to contractors who hire labour, carries the sole responsibility of ensuring minimum wage is met. And the corporation paid the dues in full after seemingly kicking the can down the road for over a decade.

One of the contractors who hired several of the women—including Vijubai—said that the contractors simply followed the rules that the PCMC put forward.

“Their fight was with the PCMC. We had no role in that, so there was no need to involve us. There was no benefit fighting with us,” said 43-year-old Sandeep Agarwal, who worked as a labour contractor and the middleman between the PCMC and the waste pickers.

I remember the fear. I remember the threats. I remember the meal the contractor fed us while trying to bribe us to back down. And I’m glad we put in the effort and didn’t lose hope, because now I can remember the victory.

– Vijubai, waste picker

“This entire city is built on the hard work that safai karamcharis put in day in and day out,” said PCMC’s commissioner, Shekhar Singh. “As of today, I can tell you 100 per cent we are absolutely paying minimum wages and we keep revising it every six months. These cases predate us—with a lack of hindsight from that time, the decision to delay paying them their wages must have been taken consciously within a particular context.”

Also read: Machines are digging, dragging, tearing into Delhi garbage mountains. Time’s running out

One of a kind victory

When she got a text message from Vijubai’s son saying the money had hit her account, 60-year-old Chaya Francis Tribhuvan didn’t dance or jump for joy. She put her phone away, and slept peacefully for the first time in over a decade.

The next morning, she went and bought herself Rs 80,000 worth of gold jewellery. She’d been awarded a compensation of Rs 3 lakh. A single woman with no children, she’d decided to treat herself. She’d earned it.

The waste pickers of Pimpri Chinchwad are no strangers to struggle—social or legal. And they’d been at war on both fronts. The war over the nonpayment of wages lasted between December 2012 and May 2013, and then from June 2013 to June 2015.

It was a complicated period, in which the waste pickers seemed to fall through the corporation’s cracks into the contractors’ clutches.

During this time, they were severely underpaid by both, receiving only Rs 3000 per month for six hours of work every day—picking, collecting, and segregating the city’s trash. They were supposed to be paid Rs 9000. When they took the matter up with the PCMC, they corrected their payment of wages and settled the matter in 2015, but two years of nonpayment had stacked up, and the contractors refused to let the rest of the money through.

The women decided to go on the warpath. And they didn’t waste any time.

It took years to forge a form of civic engagement with the municipal corporation, and an even longer period of persistent follow-ups, RTIs, and staged protests to win this case.

“This union victory is one of a kind,” said veteran unionist Milind Ranade, who is also a CPI leader and secretary of New Trade Union Initiative. “First of all, it’s very difficult to organise such workers because they immediately receive pushback from employers. But this union didn’t allow victimisation, which is an important strategy,” he said.

KKPKP has not been weakened and emaciated like other unions in post-reforms India. Extremely active in the region, the KKPKP has been the liaison between the waste pickers and the state, an integral link that has organised the workers and articulated their demands.

“The union has given us everything,” said Chaya, a string of white beads around her neck. She’s been a union member for 29 years; half her life. “Respect, courage, money — in that order.”

Technically, the PCMC got off easy. The municipal corporation is liable to pay up to 10 times the amount to waste pickers as a penalty for not adhering to the Minimum Wage Act. The total arrears they owed was Rs 3.43 crore, and the labour department ruled that the waste pickers should be twice that amount—including the initial claim and the compensation. The women all received varying amounts of compensation based on their individual claims.

The first thing that 43-year-old Manisha Hira Borade did was withdraw Rs 10,000 just to hold in her hands—she’d never held that kind of cash before. Then she went and bought mutton and chicken to cook a celebratory feast.

After twelve years, it’s a massive victory but it feels blunted. We had to fight for such a long time for something that is fundamentally enshrined in our Constitution. Over 30 people have died in this process

– Aditya Vyas, general secretary, KKPKP

Just a few months before that, she’d been so badly injured by a falling hoarding that she wasn’t sure she could ever work again. Her treatment had taken up whatever savings she had, and stitches on her head put her out of commission.

“No relatives came to check on me, but the women from our union did,” she said.

And now, when she collects trash from the house of the lawyer who fought her case, she exchanges smiles with him.

“My daughter bought me a cake the day after we got the money,” smiled Manisha through tears, a bright red clip in her hair to match her bright red saree. “She said, ‘mummy, let’s cut a cake for you — you have got a second life’.”

Also read: ‘Difficulty’ of winning lottery. Kerala sanitation workers shunned by neighbours, denied PDS

Sisterhood and solidarity

When 39-year-old Surekha Waghmare boarded the bus to court, she was thirsty, starving, and stinking of garbage. She could sense people wrinkling their noses around her—she was late and hadn’t had the time to change or eat.

She was worried that without eating and drinking water, she wouldn’t be able to speak in court and give her testimony.

But when she asked for water, no one gave her any. She heard someone whisper that her hands would be dirty because she’d been collecting trash. Their trash, she thought to herself.

The humiliation continued at the hearing. Lawyers tried to dismantle the waste pickers’ case by nitpicking their attendance at work and the money they made from re-selling waste.

The memory still brings tears to her eyes, but her colleagues and comrades are quick to comfort her. They feel like a family, getting together regularly, complimenting each others’ hair, clothes, and jewellery. Though they wear a uniform while collecting trash, they always adorn themselves with bright earrings, earcuffs and necklaces.

“You say you have no one else to support you, but you have us. We have each other,” said Vijubai firmly. The women are all between the ages of 39 and 60, but Vijubai has taken on a more maternal role.

Besides the social discrimination they used to face on a daily basis, the women have also been subjected to severe intimidation from the three contractors they collectively work for. They spent years trying to get the waste pickers to drop the case and back off.

Vijubai was a special target. Once a contractor threatened to shoot her and then shoot himself. The same contractor asked to meet her in a temple, where he offered her a bribe of Rs 20,000 to drop the case. Another time, five people showed up at her house and threatened to beat her up. Others have had threats made towards their children. The women also remember a fancy meal that the contractors once took them out to buy their silence—palak paneer, dal bhat, and parathas.

“There was fear. If anyone spoke back to the contractor, he would deny work. They thought that because we are uneducated we wouldn’t be aware!” said Vijubai.

It was both because of and despite this pressure that the women—aided by KKPKP—dug their heels into the ground to fight.

The union has given us everything. Respect, courage, money — in that order

– Chaya Francis Tribhuvan, waste picker

Sunita Dake, who doesn’t know her exact age, remembers how the contractor would deliberately try to stop her from going to attend union meetings. Some of the popular slogans they would chant were “Who says we don’t give, we won’t rest until we get it!”, “We demand minimum wages, we demand dignity at work!” and “Long live women’s empowerment!”

“I told him that my time belongs to him only during work hours,” she said. “After work hours I can do whatever I want—I can watch a movie or I can go to the union.”

But Vijubai’s greatest anger and disappointment is not aimed at the corporation and the contractors—she’s angry with the few waste pickers who succumbed to pressure and met with the contractors behind the women’s backs to collude with them.

All the women around her nod. The betrayal cut deep, a slap in the face of their common cause.

“Some waste pickers from our organisation broke away and formed their own faction to dissuade us. They deceived us and took our signatures on a form saying that we would not go to court. But it didn’t sit well with me,” said Vijubai. “I told them that I will be on the side that looks after the wellbeing of women like me.”

“That’s what we call a union—coming together,” said Rekha, holding Surekha’s hand.

Ironically, one of the men who’d threatened to beat Vijubai up was also the first person to message her after the implementation of the order— asking whether she’d actually received the money, and to send him a screenshot to prove it.

There was fear. If anyone spoke back to the contractor, he would deny work. They thought that because we are uneducated we wouldn’t be aware!

– Vijubai

First encounter with the legal system

Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat was named after the waste that itinerant waste pickers would pick up—paper, glass, metal. That’s how old the union is. If they had to rename the union today, they’d include the word “plastic”.

The trash trail in Pune, an hour away from Pimpri Chinchwad, was formalised because of the KKPKP’s efforts. Their programme, SWaCH, revolutionised waste collection in the city through door-to-door collection, in which citizens pay a user fee to waste pickers. It’s been such a successful model that the Pune municipal corporation has renewed the contract for decades, creating a relatively safe and standardised environment for waste pickers in the city and allowing them to have more autonomy and control over their own work. The shorter work hours and the standard pay made it a lucrative option for migrants in Pune—it is no longer limited to just the Matang and Mahar castes.

“It allowed waste pickers to go from invisible to being part of an ecosystem,” said Harshad Barde, director of SWaCH. “And this pathway allowed for informal and itinerant waste pickers to enter this system. Today we have a scenario where urban poor who’ve never touched waste want to take up this job in Pune.”

The waste pickers from Pimpri Chinchwad had a brush with the modern way of doing things when the PCMC approached the KKPKP to implement a similar model in the city. They wanted to introduce mechanised waste collection and had the money to spend on it.

Earlier, the waste pickers would simply collect trash door-to-door. Now, they would do it with a tiny truck, complete with a driver they could source. Most women ended up relying on relatives or acquaintances looking for jobs.

The PCMC decided to try the method out by splitting the city into two zones. In one zone, waste pickers followed the SWaCH model. In the other, contractors were used to employ waste pickers.

Ultimately, SWaCH decided to pull out— citizens were unhappy paying the user fee when they had a choice to pay nothing under the contractor model, and the PCMC decided to continue with the contractor model.

The waste pickers hit their first hurdle in Pimpri Chinchwad: the waste pickers from the SWaCH half would first have to be integrated into the contractor setup.

“Their incomes grew but their status didn’t,” said Barde. “The waste pickers went from being owners of the model to being strong workers to being relatively weak workers under the thumb of the PCMC.”

This is when their encounter with the legal system truly began.

They were formally employed by the corporation’s contractors in 2012 after the workers filed a PIL at the Bombay High Court. And then the discrepancy in their wages began—they realised they were being shortchanged when they started receiving significantly less money from the contractor than they were making in the direct model under SWaCH.

They demanded the money from the contractors several times—attempts have been made to settle the case too. The women remember the contractors’ taunts and threats. “As if you will be able to get any money from the corporation!” they’d say. “We’ll see you in court! Let’s see what you can do!”

It wasn’t just the contractors who were cheating the 300 or so waste pickers who had to be integrated into the new PCMC contract, the corporation was underpaying the contractors too. They were paid Rs 6000, half of which they pocketed. Only Rs 3000 would go to the waste pickers instead of the rightful Rs 9000.

This cycle continued until the waste pickers decided to go to court.

Their first brush with the law was quick. The workers filed a case against the corporation for violating the Minimum Wage Act in 2012, and the corporation corrected the payment, closing the case in 2015. The verdict was in the waste pickers’ favour: many received partial amounts, between Rs 30,000 and Rs 50,000.

Then they filed a case against the three major contractors for withholding their wages in 2015, which finally ended with the corporation being held liable as the principal employer in 2023.

“It sends an important message: if you fight, there’s a possibility that

you can win even when the socioeconomic structure is not at all in your favour,” said Ranade.

The union and the women

Each attributes the legal victory to the other—the waste pickers say it wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the union, and the union says they wouldn’t have been able to truly push this case without the waste pickers’ own interest in it.

“We did the technical work,” said Barde, who’s been involved in the case since the start.

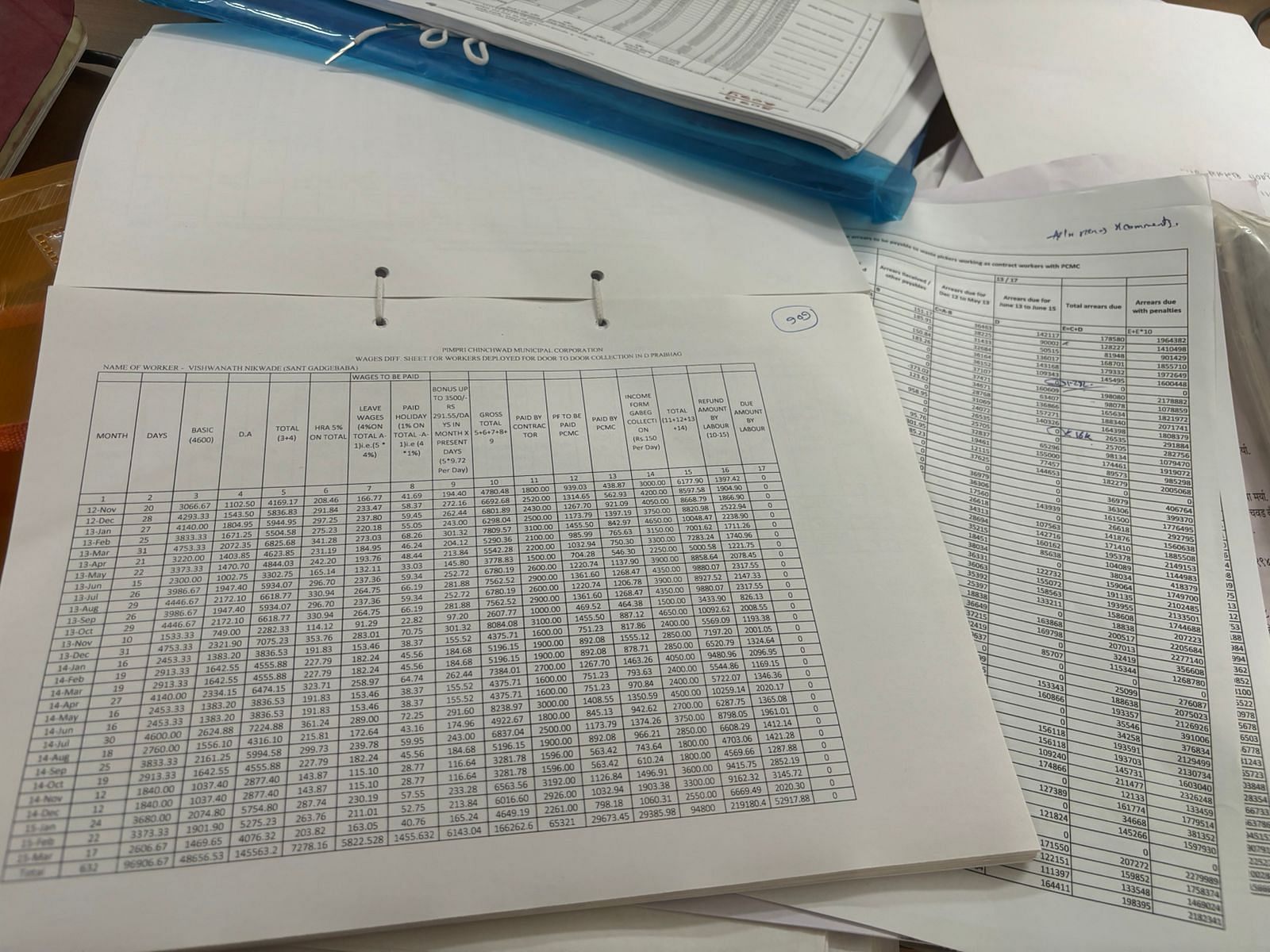

And it was hard work. The union members had to do all the research and calculations to collate information and data—from filing RTIs to getting attendance numbers between 2012 and 2015 from the municipal corporation to calculating provident funds for each of the 300+ waste pickers.

“90 per cent of this case was done on Excel sheets. We wouldn’t have been able to do this without Excel,” said Barde, laughing.

But he said that they didn’t need to motivate the waste pickers.

“That’s all them—the members kept it alive because they were very clear that this is their right. So we did our best to support them,” he said.

The women had a routine at court. Vijubai, Chaya, Shital and Surekha always tried to attend in groups, marking their physical presence in front of the labour department each and every time. Vijubai was often early and would update the others over the phone until they arrived in person.

They would do their regular waste-picking route in the morning and then rush to the labour court at the municipal corporation with their packed lunches, usually bakhri, to share with each other so no one went hungry. Fried snacks at the municipal corporation’s canteen slowly became a favourite indulgence after lengthy hearings and cross-examinations.

Time was always of the essence on hearing days. Sometimes, the women resorted to taking autos across the city to make it to PCMC, even if it was an extra expense.

I can’t stress how rare it is that the order was implemented and they actually got the money. This never happens. Their capacity to fight is very important.

– veteran unionist Milind Ranade

They had to run pillar to post, constantly following up with various government departments and applying as much pressure from as many different sides as possible for over a decade. Even after the case was won in August 2023, it took nine months for the money to hit their accounts.

They would sit on the steps outside the municipal corporation waiting to catch a hold of the municipal commissioner and members of the health and labour departments. They would constantly nag lawyers and union leaders to follow up for them. They even agitated at the winter session of the Maharashtra assembly in Nagpur. It was there that Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar took notice of the case and inquired why the money hadn’t been deposited yet. This intervention helped hurry the transfer.

“I can’t stress how rare it is that the order was implemented and they actually got the money. This never happens,” said Ranade. “Their capacity to fight is very important. This, along with the right social and political connections and the fact that elections were around the corner worked in their favour.”

But there’s no real explanation for why there was such a delay—in both the case and the payment.

“It shows the inherent dislike and distrust of the working class by the administration. What else can explain it?” asked another union member.

Also read: Life in India is easier than in Canada—because they respect their labour and we don’t

Bureaucratic indifference

Yashwant Dange, the assistant commissioner of the health department, proudly displays a 2023 5-star rating from the Swachh Bharat Mission for Pimpri Chinchwad in his office.

It’s a rating the PCMC is proud of and is hoping to top with a 7-star rating soon. Creating civic ownership in the city is important, according to Dange.

“We have 100 per cent waste collection and segregation, and good maintenance of the same. Our city is extremely clean and we also have mechanised sweeping,” said Dange, under whose jurisdiction the waste pickers technically fall.

But they’re still outsourcing the work to contractors. However, Dange said, they’re now checking the bills very carefully to ensure a lapse doesn’t happen again.

“Being principal employer, we had to pay the waste pickers,” said Dange, adding that they didn’t file a counter or appeal the case on humanitarian grounds. “We’re also initiating legal proceedings against the contractors.”

Agarwal, one of the contractors, said as far as he’s aware all proceedings are done and dusted, and they’ve not heard of any such legal proceedings from the PCMC.

“Ho gaya na sab? (Everything is done, right?)” asked Agarwal.

Municipal commissioner Shekhar Singh conceded that there’s still a lot that every municipal corporation—including PCMC—can do, especially when it comes to the social upliftment of waste pickers so that their basic occupation isn’t threatened by the mechanised technology that’s coming in. Integrating them into the formal economy is still a while away.

“They’ve been fighting for it for quite some time,” said Singh. “We realised it doesn’t make sense to go into an endless legal cycle, and we wanted to pay them what they are owed.”

Singh recognises the role KKPKP played—waste pickers like Vijubai, Manisha, and Chaya wouldn’t have as strong a voice without them.

The women were often villainised in court. One day, the corporation’s lawyer turned around and accused the women of being thieves. The lawyer accused the women of stealing and making money from re-selling trash collected from wealthy households.

“They don’t need the compensation because they were already making money like this,” they remember the legal team saying. Another lawyer said he was too busy for a case as small as this—he had more important work at the Bombay High Court, and was disgruntled at being dragged to PCMC to waste his time on waste pickers.

But after the verdict, they were upheld as integral to the city and its clean civic image.

Ranade, who organised the first-ever union for sanitary workers in Mumbai in the 1980s, added that KKPKP and the women followed an intelligent strategy and fought on the correct legal lines.

“Neither the contractors nor the municipal corporation realised they’d end up giving them money—they thought they were harmless creatures, like the Lions Club or something. This is a learning lesson for unions across India, as well as exploitative employers,” said Ranade.

Part of the problem was bureaucratic indifference: all it took was the right constellation of concerned, empathetic bureaucrats such as Shekhar Singh to make sure that justice was served.

“Because of their apathy and inaction, the liability of the corporation and the contractors increased as time went on,” said Vyas. “It was just inaction. And we couldn’t figure out why. Everyone knew the PCMC had to eventually pay up.”

‘Mummy isn’t scared now’

Vijubai’s 21-year-old son, Omkar, has two phones: one for official business and one for personal use. He was only ten when the case began.

He’s busy fielding phone calls on his work phone from a worried union member whose husband needs Rs 4 lakh for surgery. He’s not sure how they can arrange the money, but knows it’ll work out. Omkar joined the union right after he turned 18, in part because he saw how the union changed the way his mother sees herself but largely because he wanted to protect his community.

“This hope, and confidence, for change is the most important thing that both sides have found,” said Vyas. “It’s a victory for the idea of unions too.”

While he’s never faced any discrimination at school for his mother’s job, Omkar’s also never spoken to his friends and people his age about the legal battle. They don’t know about the struggle his mother had to go through, and he’s vehemently kept it that way.

“This one issue has come to a conclusion, but there are others, like securing scholarships for our children,” said Vijubai.

These scholarships are an important way out of the social hierarchy that has kept their families entrenched in this form of labour, and is a project that KKPKP is focusing on.

“Our parents do not want us to do this dirty work. They say it should end with their generation, they say ‘gandagi mein mat aao’ (don’t be part of the filth),” said Omkar.

None of their children work as waste pickers today. One son has joined the Navy, while another is working as an engineer. Omkar himself wants to enroll in law school and become a lawyer to supplement his activity at the union.

“I want to know how the other side thinks, I’ll get to know all the tricks that lawyers use,” grinned Omkar, having grown up in and around courtrooms.

And he’s determined to make sure no one around him will face the indignity his mother did.

“Now mummy isn’t scared at all, and we want to keep it that way,” he said, a proud smile on his face.

Vijubai remembers how she’d hide her face in the courtroom to avoid the contractor’s glare, making whispered phone calls to union members to let them know he’d arrived.

“He used to look at us with such anger in his eyes, saying he would see us in court,” she said.

And moments after they won the case, she remembers locking eyes with the same contractor. This time, despite losing the case, there was a taunting smile on his face.

She quickly looked away from him. She didn’t want to waste another minute of her life on him. And she hasn’t looked back since.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)