Panipat: Dr Datta Valekar arrived at Kala Amb Park in Haryana’s Panipat on a recent Sunday, all the way from Beed, Maharashtra. He was retracing the path his Maratha ancestors had taken 250 years ago, to the site where their blood had flowed like water after they were defeated on one of Indian history’s most storied battlefields—Panipat.

But his tryst with the past in Panipat, the city of loss, was nothing like the grand embrace he had imagined all his life.

Valekar, 26, scanned every inch of the underwhelming park. He stared at an insipid, charcoal-grey mural depicting the fierce battle between Ahmad Shah Durrani and the Marathas. He paid his respects at a solemn pillar, marking the spot where, under a mango tree, so many of his people had perished.

“Coming here was supposed to be special for me,” he said, disappointment etched across his face. “But there’s nothing here. There are no memorials.”

Three historic battles were fought in Panipat, an otherwise missable town littered with phantom spirits of Indian history’s seismic losers, each straining to be remembered as a winner. The first saw the Delhi Sultanate under Ibrahim Lodi crumble under the might of Babur in 1526. Thirty years later, Hemu Vikramaditya lost to Akbar. Finally, in 1761, the Marathas faced Ahmad Shah Durrani, their ranks facing a brutal defeat.

Today, the battles of Panipat are used as political ammunition. Earlier this year, Jyotiraditya Scindia visited Kala Amb to pay homage to his ancestors, who had sophisticated weaponry but not the foresight to carry enough food. Home Minister Amit Shah famously likened the 2019 general elections to the third battle of Panipat. During the Maharashtra election campaign, he also became the Shiv Sena’s personal Ahmed Shah Abdali. The pain of Panipat’s bruising civilisational wounds continues to resound in metaphors, songs, and politics.

The fight to retain Delhi never gets old–except in Panipat.

The losses have become the leitmotif of a city that would rather be known for making blankets. Over time, the wounds have ossified into apathy. The memorials and museums are confused and in disrepair. Panipat is trapped between a history book identity of losing as well as the urge to break away from it. The Panipat Museum is a testament to this: its walls are peeling, the bathrooms have no running water, and electricity can be hit or miss. Academic rigour is missing in the absence of the city’s own university. A green structure could either be the Samadhi of Hemu or the dargah of a local imam. The Maratha temples have been quietly razed. Unlike Lucknow and Amritsar, which wear their scars with pride, Panipat and its people refuse to attach themselves to this identity. Their past is now irrevocably divorced from the present.

The first battle of Panipat saw the Delhi Sultanate under Ibrahim Lodi crumble under the might of Babur in 1526. Thirty years later, Hemu Vikramaditya lost to Akbar. Finally, in 1761, the Marathas faced Ahmad Shah Durrani, their ranks facing a brutal defeat.

Panipat wants to be known as an industrial hub, a textile mecca, and the hometown of Olympian Neeraj Chopra.

The daily scene here sees elderly residents gather to play cards in parks but leave by tea time.

“Panipat isn’t defined by its history. It’s defined by its blanket factories,” said a resident. “It’s just an industrial town. Once in a while, tourists come.”

Also read: Panipat men are becoming Hanuman for 41 days. No salt, no women, only tapasya

Panipat’s history enthusiast

A beaming exception to this largely lackadaisical relationship with the past is Chand Singh, a history professor at DAV College in Ambala. His eyes lit up as he explained the geographical dimensions of the third battle, turning the paperweight on his desk into Babur and Maratha emperor Sadashiv Bhau.

Singh left Panipat two decades ago, but his career trajectory was determined during childhood while playing gilli-danda outside the tomb of Ibrahim Lodi.

“That’s where my interest in history really began,” he recalled.

Singh’s research focuses on mediaeval structures, and his hometown guides his academic pursuits—the abject neglect shown to Panipat’s historical sites, their character now erased under the garb of beautification. The beautified monuments, including sections of Kabuli Bagh and the Devi Mandir, are flashier to make them appear more impressive.

For all the obsession with Panipat’s battles, Singh laments the missing historians and specialised courses in local universities. “Mediaeval history as a discipline is dying in smaller towns,” he said. “There are diploma courses on excavation and archaeology, but history papers are too general and non-specialised. We’re not being able to generate interest in this time period.”

Nothing has changed in Panipat since Singh left. Lodi’s tomb is now just an insipid green park with playing cards floating in blackened water—a far cry from the sprawling grandeur of Delhi’s Lodi Gardens. The Archaeological Survey of India isn’t very verbose either. It acknowledges the Panipat monument only with a modest signboard reading “historically significant”, which hardly befits a battlefield where an army of over one lakh soldiers was defeated by one of 12,000.

Like Chand Singh, there are those who stumble upon the tomb by accident during evening strolls. Their interest is piqued. But unlike the historian, it’s a fleeting moment. “Is this for publicity?” local resident Monty Singh asked, referring to the ASI board that states the tomb as belonging to Ibrahim Lodi. With no answers or signage tests, they resume power-walking.

Mediaeval history as a discipline is dying in smaller towns. There are diploma courses on excavation and archaeology, but history papers are too general and non-specialised. We’re not being able to generate interest in this time period.

Karamvir Kadian, a Haryana tourism official, is convinced that Panipat’s tourism potential lies in its past. But in this industrial town, Skylark—the tourism department’s hotel—exists only for business travellers. Even in this age of pop-history and spiralling narratives, Panipat still can’t hold its own and its historic battles remain just that—battles that, for most, are better left in history books. The restaurant at Skylark is not only drab, but empty.

Hemu’s forgotten legacy

The histories of other losers are also trapped in similar neighbourhood apathy.

In Panipat’s largely residential area of Saudhapur, a domed structure stands. Both the Haryana museum and local residents recognise it as Hemu’s Samadhi. Hemu, a Hindu general in an Afghan army, supposedly died here pulling an arrow from his eye during the second battle of Panipat, where a 14-year-old Akbar won the day.

His memorial is also mired in a web of confusion and a bilious green paint-job. The Haryana tourism department lists it as Hemu’s Samadhi Sthal on its website. But there’s confusion here as well. Muslim residents visiting the mosque call it a dargah that is occasionally used by local imams.

Hemu, a Hindu general in an Afghan army, supposedly died here pulling an arrow from his eye during the second battle of Panipat, where a 14-year-old Akbar won the day.

“There’s an imam who places a chaadar here from time to time. But it’s mostly locked,” said Shah Muhammad, present at the mosque to read namaz.

The Haryana Waqf Board, which manages the property, only records it as a ‘Dargah Mosque’. There’s no mention of Hemu or Qasim.

“There are no allotment papers or revenue records that call the building Hemu’s Samadhi,” said Moinuddin from the Waqf Board. “It’s just a narrative that’s taken hold. I don’t understand what’s happening.”

The monument pales in comparison to its neighbour, the family home of Gurmukh Singh—which is grander and better maintained. There are boards announcing it as a ‘Thakral Mansion’ and that his two daughters are lawyers.

“I don’t know where Hemu died. Maybe he died in the village. This is just an old dargah,” Singh scoffed. “Only in the past two decades have the authorities started calling this Hemu’s Samadhi.”

He has seen the narrative shift. When his family moved to Panipat in 1950, after spending three years at a refugee camp in Amritsar, they had nowhere to go and so lived in an unnamed green building. Later, they built their home and took up farming. The green building became a storehouse for their buffaloes.

In 1986, a couple of Muslim families moved in across the road. They entered into an informal agreement with their friendly neighbourhood Sikhs and began using it to read namaz.

“There was nothing here then. It was all jungle. The only sign of civilisation was this one building,” said Gurmukh Singh, who also runs a corner-shop from his home. When he was a child, the rumour was that the samadhi was haunted. He claims to have once seen a mangled limb behind it.

Singh is convinced that there’s more to the story of Hemu than meets the eye.

“Akbar shot an arrow and we think he died. But what if he ran away and died elsewhere?” he said. When he was young, villagers used to believe that a haveli that has since been demolished was the site of the great commander’s death.

Hemu is the loser who received the short end of the stick. Not everyone is convinced this is his site.

According to Singh, a researcher came just last month—in search of Hemu’s Samadhi. “Did he think he’d find a treasure here?”

The sign outside is indecipherable and has turned a burnt ochre with age. A buffalo lounging in the mountain of trash outside the purported samadhi makes a sudden movement. The garbage on which it is sitting has been set on fire. Hemu is nowhere to be found. And neither is Qasim.

The Kabuli Bagh Mosque

It hasn’t been easy for the victors either. They are plagued by another obstruction—they’re no longer on the right side of history. Case in point: Babur’s Kabuli Bagh Mosque, built as a chest-thumping ode to himself in 1527, the year after his victory.

The mosque’s gate is sealed shut with a rusted lock bound by an equally well-worn chain. The caretaker deigns to open it upon being requested, rising from his charpai. Children from the neighbourhood scale the ASI-built boundary wall to play football, which occasionally bounces off a nearly 500-year-old inscription.

Their nonchalance stands in stark contrast to a solitary professor’s dogged research.

In 2008, a persistent Chand Singh published a paper on the condition of Kabuli Bagh, which showed that ‘repairs’ undertaken by the ASI were attempts at embellishment. Two minarets were added to the mosque’s northern gate. Mughal architecture is decidedly uniform, but here too the ASI has taken certain creative liberties, he claimed.

There are two dramatically different flowers engraved into the mosque. One has imperfect edges and plaster that has given way. The other is immaculate, almost as if it was conjured days ago. Its petals are perfectly symmetrical and it’s framed by a bathroom tile-esque border.

“The monuments of Panipat received their ASI tags late, after the neighbourhoods had come up,” said Suresh Kumar, an ASI Haryana circle field officer, based in Panipat. “And the town’s identity isn’t the battle. The blankets are more famous.”

According to Singh, this is only the tip of the iceberg. The inscriptions above the flowers, he said, have been “mutilated.”

“In the last decade of the 20th century, the majority portion of the inscription was destroyed. In the future, questions will be raised on its originality, time-period and historical identity,” the professor said.

Babur’s physical rendering of his epochal victory is a public loss. The writing on the plaque is barely discernible, and the narrative is missing. But its wrought-iron gate is unlocked upon request.

“We have to keep it locked. Our children are mischievous. They can do anything,” whispered Rajesh, the mosque’s lone caretaker, who took over after its previous manager passed away. Kabuli Bagh is apparently an incubator for Panipat’s “anti-social” elements—other than a local football field, it’s also known for building a gambling habit.

Also read: Panipat was a bloody military debacle for Marathas. Will patriotism-high India see the film?

Battles of Panipat in pop culture

In today’s public consciousness, the battles of Panipat are often routed through humour, more as myth than as reality. They’re prime fodder for history memes, which distill centuries-old events into digestible and often comical snippets.

Take the first battle, for instance, best explained by Mad Mughal memes. Babur is a suave foreigner out of a Western film, while Ibrahim Lodi is parochial and doddering. Babur takes a single shot and Lodi is done for.

A Reddit discussion dissects Sadhashiv Rao’s military strategy during the third battle, concluding that he shouldn’t have abandoned guerrilla warfare. A user even compares Rao to Brij Mohan Kaul, the maker of India’s military strategy during the 1962 India-China war.

“They [the Marathas] lost a battle they could have won, and in this aspect Rao is similar to Kaul,” reads the comment.

Such reinterpretations aren’t confined to unpopular internet spaces. They have moved beyond meme pages to enter the mainstream political discourse. In the run-up to the 2024 Lok Sabha election, an op-ed in The Sunday Guardian compared opposition leaders to the Marathas—unwitting losers who, even after defeat, continue to create trouble for the ruler.

And both losers and winners continue to be a part of today’s political spats. Union Home Minister Amit Shah once called Uddhav Thackeray’s Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) alliance the “Aurangzeb fan club,” to which Thackeray responded by calling Shah “Ahmed Shah Abdali”—the divider in chief of yore.

Also read: Forget battle over the film, Panipat is at the heart of 3 battles that shaped our history

The Panipat Museum

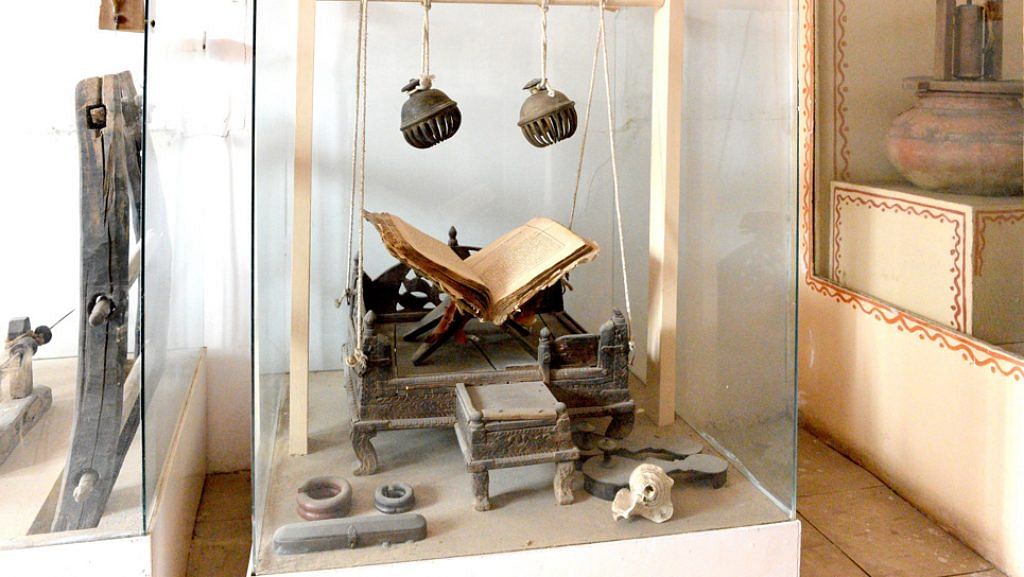

Located on the city’s outskirts, the Panipat Museum does not have answers either. But it does have galleries dedicated to each battle of Panipat and one on Haryanvi culture, which includes sculptures and artefacts from across the state. On a Thursday afternoon, there is no electricity and visitors are clicking pictures outside in the garden rather than exploring the exhibits. Plaster from the ceiling has peeled off and there’s no running water in the bathroom.

In the third battle gallery, a Maratha soldier and an Afghan soldier face each other. There are school textbook-like inscriptions on the walls, describing paintings of the battle, sourced from the national museum and the British Library.

There’s also a map of Panipat, which zeroes in on the spaces relevant to the battles. “We wanted to visit Panipat because it shaped our country’s history,” declared Chan Basha, an IAS officer from Chennai. “This is where strategic battles played out and the fate of incumbent rulers was decided.”

But the deciding factor for him were the Marathas and the role they played in defending Delhi from Afghan invaders. He’s not the only one.

According to Trilok, the caretaker who oversees the museum’s daily operations, the largest visitor base is from Maharashtra.

“The Marathas want to see where their ancestors shed blood,” he said gravely.

But their desire to be remembered isn’t enough to preserve the physical sites of remembrance. Professor Singh’s work, published by the Indian Council of Historical Research, found that in Devi Mandir, a temple complex and one of the city’s pride points, two Maratha temples dating back to the 18th century were demolished by the management committee—a family of priests—as part of their private beautification efforts between 2013 and 2019. These were small, unobtrusive temples. One was a Shiva Temple and the other a Vishnu temple. Both were constructed in the decade after cataclysmic loss.

“There’s no care afforded to our mediaeval structures. It’s only in big cities,” he said mournfully.

At Kala Amb, Valekar’s journey was cut short due to missing tourism infrastructure. But the images of war and Maratha pride run deep.

“We only lost the battle because we didn’t have enough food and water. Otherwise we would have won,” he said of the third battle that cost the Marathas Rs 93 lakh and between 60,000 and 70,000 lives.

“Our country’s best people are Marathas,” said Valekar. On his list are Pratibha Patil, Neeraj Chopra, and Jyotiraditya Scindia.

And their identities originate in Kala Amb, where a young man in cycling shorts stretches his legs. His pants have been abandoned on a bench next to the sombre mural at which Valekar stares.

(Edited by Prashant)

Wonderfully written article. Such a sad state of affairs – these battles determined India’s future. Which means we and our lives have been shaped by the outcomes of the battles of Panipat. Every nation – from Turkey and Georgia to the European nations and the US – has preserved its past so well. Wish India too, gets it’s act together.