Patna/Bakhtiyarpur/Purnia: When a caste census enumerator showed up at the home of 85-year-old Rambaran Singh on Tuesday lugging a big black bag, there was some flutter, some apprehension. The enumerator uttered the politically controversial and somewhat dreaded term ‘jati janganana’ and took out a large form with dozens of rows and columns.

Singh’s caste — Kushwaha — is numbered 26. It’s a community of farmers among Bihar’s OBC groups. He says he doesn’t know what benefits the census will bring. “Even if there is an advantage, I will hardly be alive by then,” the resident of Thadha village in Purnia district said.

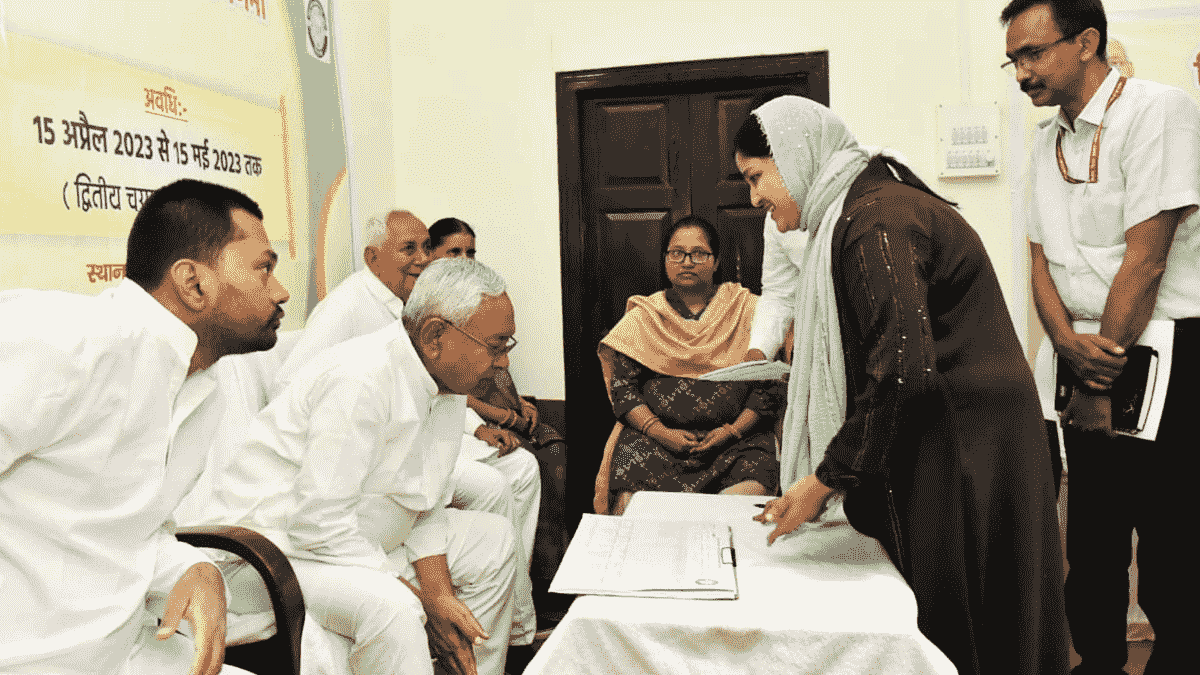

After the first phase from 7-21 January 2023, the second phase of the ambitious caste census in Nitish Kumar-ruled Bihar started on 15 April, with enumerators arriving in villages all over the state in the blistering heat and going door-to-door to collect detailed information. They aren’t supposed to ask for any document — and record only those details that people give voluntarily. The census is an exercise that is more political than social in Nitish Kumar’s opposition politics.

But it’s a count whose time has finally come.

All the caste conversations freed up after the Mandal Commission report in the 1990s have led to this moment. Lakhs of people have been counted and a target has been set to complete the census, which the CM started from his ancestral home in Bakhtiyarpur, by 15 May.

Singh’s courtyard overflowed with open heaps of freshly harvested maize grains. A dim bulb on the wall was not providing enough light. Seventeen questions follow.

“So much information has to be filled… maatha pagal ho gaya hai (I am losing my mind),” he fumed.

The word about the enumerator has spread. Other curious villagers drop in to watch the process, even before their turn comes. Many are carrying their Aadhaar card even though it’s not required.

Also read: Bihar is talking caste census but with Mandal memories — Hope, anxiety, fear

It’s a difficult conversation

Kahkshan is a 41-year old teacher, but she spends less and less time at school nowadays. She has been enlisted by the Bihar government to be a census enumerator in this tricky, sensitive count and leaves her house in Purnia every day at 6 am and travels 15 km to reach Thadha village, where she has to conduct the census in 100 homes. But the conversations can often be delicate and she can’t dive right into the list of questions. The enumerators skirt around other themes first.

They ask about the harvest, heat, health and even patriarchy to put family members at ease.

“The month of Ramzan is going on and it is very hot, so we have to leave the house early in the morning. People are usually asleep when we arrive. They have to be told that we have come for the caste census. Most do not know about it. They are speechless,” Kahkshan said.

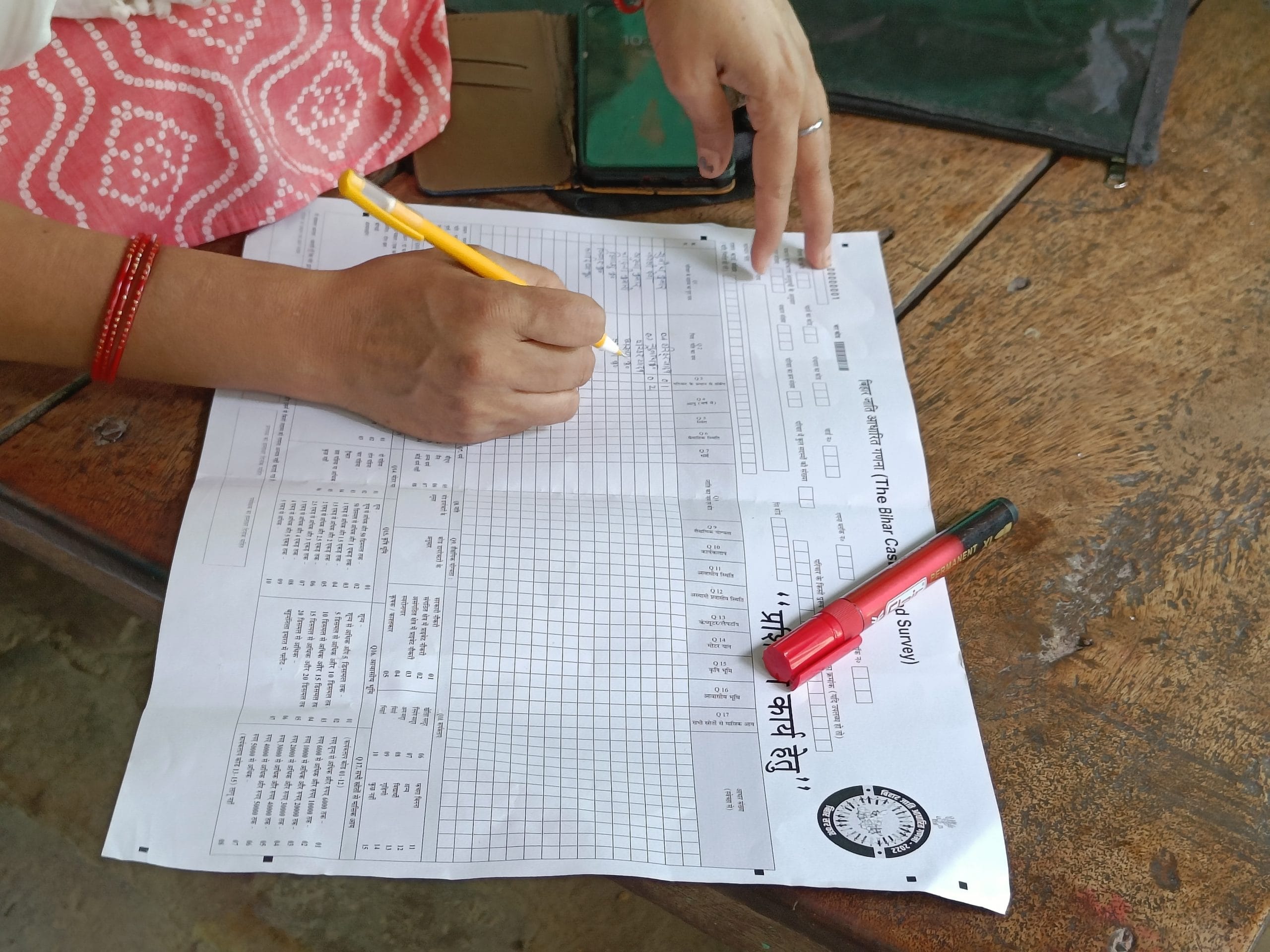

Enumerators complain that they have no assistant to help them count. Filling all the information can get complicated because everything is coded. The booklet given to them contains 215 caste codes. And the 17 questions seek information regarding the educational qualification, members in the family, their gender, and residential status—each with its own code.

It’s why enumerators use a pencil to fill the form, take the signature of the head of the family using a pen, and return home to fill the entire form with a pen before uploading it on the ‘Bijaga’ (Bihar Jatigat Janganana) app, developed by Trigyn Technologies. The app itself is a cause for worry. “It gets stuck at Nitish Kumar’s face,” said a teacher who did not want to be identified.

Kahkshan enters the codes slowly and carefully, cross-checking with the booklet multiple times. It’s why some of the teachers bring their husbands with them. A second set of eyes always helps.

The villages may be far flung and difficult to navigate, but it’s the cities that are more challenging for enumerators. They encounter public apathy, cynicism, and empty homes.

By the time 45-year-old Shubha Kumari, a school teacher in Patna, reached her designated area for counting around 10 am on Monday, people had left for work. Their houses were locked.

In one of the houses, resident Chandni Kumari was distracted by her three-year-old son demanding her attention. In the adjacent house, the resident told Shubha she didn’t have time for her questions.

Karu Yadav, in Mithapur, sits on the ground silently staring at the form. He does not know about the census. “Eko class nahi padhe hain (I never went to school). Inflation is so high, we are busy with our livelihood. Who has the time to talk about caste census?”

Also read: Rahul Gandhi can drive Mandal 3, reverse social justice politics that BJP pushed to dead-end

Census and the list of troubles

Bihar’s caste census is no stranger to controversy or disagreements. It aims to gather information from 12 crore citizens. Each of the state’s 38 districts has 2.58 crore households.

The latest concern is over denoting transgenders as a caste. A PIL was filed against this in the Patna High Court on Tuesday.

On the other hand, the over 50,000-strong Sikh community in the state wants its own caste code.

“Sikhs haven’t been assigned a separate caste code like the Christians and Muslims. Sikhs should also have one,” Trilok Singh Nishad, head of the Shri Sanatan Sikh Sabha, Patna Sahib, had said.

The chief minister’s decision to not count sub-castes has also ruffled feathers. As a result, the Gwalas and Ahirs will not be enumerated.

When a family in Patna told their caste to enumerator Shubha Kumari, she replied by saying that what they had mentioned was their sub-caste, not caste. “You are a Yadav. Your caste code is 165. Remember this. It is now your identity.”

Thirty-two-year-old Vinod Mishra from Saharsa doesn’t support the caste census. “Yadavs and Kurmis have been ruling Bihar for the last 30 years. After the caste census, more difficulties will arise for the forward castes,” Mishra said.

Outside the magistrate’s office, 55-year-old Jogendra hopes the caste census will change things in the state and in his life. “I am from a lower caste, Teli, code number 83. It should be calculated. The government’s slogan of Sab Barabar Hain (everyone is equal) hasn’t led to us getting representation.”

The BJP has tapped into this season of discontent, warning that the omission of sub-castes could derail the quota system.

“The CM perhaps does not want sub-castes to be counted so that it is not revealed that his own OBC Kurmi sub-caste, Awadhiya, is very small in numbers,” BJP state president Sanjay Jaiswal said in an interview with The Indian Express during the first phase of the census.

Hindutva alone was not enough to make inroads in Bihar where almost every caste has a sub-caste. There are anywhere between 2,500-3,000 sub-castes in the state. For comparison, Karnataka has 101.

As part of its strategy, the BJP started reaching out to some of the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) through samajik samrasta (social harmony) campaigns.

“Having consolidated its existing support base around a larger Hindutva identity, the BJP has been trying to expand its presence among the OBCs and undercut the support for state-level parties, who depend on the OBC vote. Nitish Kumar is countering this political game of the BJP with the caste census,” said Vikas Kumar, an associate professor at Azim Premji University.

Glitchy app, PIL on transgenders, omission of sub-castes, recalcitrant citizens, and a scorching summer aren’t the only bumps in the caste census. The ongoing protest by teachers unhappy with the new recruitment rules is adding to the trouble. Most of the enumerators are Niyojit teachers—those appointed since 2006 who will now have to take the recruitment test again if they want to become permanent government employees.

On 18 April, they demonstrated outside district headquarters all over the state while many unions have boycotted the caste census. The government, though, has remained unmoved.

“Counting is a government job. They have government jobs and cannot run away from it. They have to do it within the stipulated time,” RJD spokesperson Mrityunjay Tiwari said.

Also read: Not counting, won’t let states count either—Modi govt’s message on caste census

Rare caste census unity

Other states are watching the events unfolding in Bihar closely. There is a lot of discussion about a similar caste census in Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, and Uttar Pradesh. While demand for a caste census is not new, it is the first time political parties across the country have widely endorsed it.

MK Stalin, Sharad Pawar, Mayawati, Akhilesh Yadav—all have urged the Centre to conduct caste census along with India’s decennial census. The reasoning is that the latest data on caste — which is the basis for a number of central and state welfare schemes — may give a fillip to regional parties looking to mobilise support to counter the BJP.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, who is campaigning in Karnataka, which goes to polls next month, spoke about a new political strategy with a focus on backward classes. At a rally in Kolar on 16 April, he said knowing the numbers of each class was necessary to ensure political participation. “Jitnii abadi, utna haq,” he said, referencing BSP founder Kanshi Ram’s slogan: Jiski Jitni Sankhya bhari, utni uski hissedari. He accused the Modi government of “hiding” the results of the Socio Economic and Caste Census (SECC) carried out by the UPA government in 2011. Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge has written a letter to PM Modi demanding the release of the SECC data.

The 1931 caste census—under British rule–was the last one to be published. The SECC-2011 findings were never made public on the grounds that the study was riddled with errors and the data unusable.

The demand for caste census is directly related to the 50 per cent cap on reservation. Opposition parties have repeatedly said that reservation for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) has broken this cap, and that a caste census where OBCs are counted will make reservation easier. It’s an attempt to re-invent the ‘Mandal’ — a term used to describe caste-based politics — and counter the BJP’s ‘Kamandal’ or Hindutva plank, as ThePrint reported on 19 April.

There was a time when almost no political party wanted to stir the hornet’s nest by undertaking a caste census. The Yogi Adityanath government in Uttar Pradesh, in its first term, had undertaken a ‘samajik nyay’ (social justice) survey, which outlined more representation for lesser represented Dalit and OBC groups, but the report hasn’t been implemented yet. Karnataka, which did conduct a caste census between 2013-2018 when Congress party’s Siddaramaiah was the CM, has not made the data public.

After Nitish Kumar first came to power in Bihar in 2005, he would often say that he supported the jamaat (masses) and not jaat (caste). But his stand changed with each passing year. In 2006, he announced 20 per cent reservation to the EBCs in panchayats and local bodies. And in 2007, Kumar formed a commission that identified 21 Scheduled Caste groups as ‘Mahadalit’, creating a sub-group of Dalits.

In 2018 and 2019, resolutions regarding caste census were unanimously passed in the Bihar assembly. Although all parties, including the BJP, supported the census, the Modi government in September 2021 filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court saying that the caste census was “not feasible”.

It became a bone of contention between the JDU and BJP during their alliance in Bihar. In August 2021, CM Kumar met PM Modi to discuss the case census. The following year, the JDU parted ways with the BJP, and formed a government with the RJD. On 6 June 2022, the Bihar government issued a notification saying the caste census will be conducted.

The BJP insists that it’s not against a caste census.

“Our party has supported the caste census in the state from the very beginning. Things will happen at the national level on the basis of what the central government decides,” said BJP national spokesperson and former Bihar industries minister Shahnawaz Hussain.

Nitish Kumar’s JDU, though, would have liked the census to be conducted nationally.

“The Center has committed an injustice. Right now we are doing it at the state level. If it was done at the national level, people would have got a lot of benefits,” JDU MLC Ravindra Singh said.

The outcome of the caste census will be felt among other religious communities as well. Now that Pasmanda politics is becoming the new catchword in northern India, the results of the census will play into that as well.

The BJP is simultaneously engaged in wooing the OBC and Pasmanda communities, which are part of its social engineering. “The caste census is a counter to the social engineering of the BJP,” said Prof Vikas Kumar.

Caste census has been one of the main demands of the Pasmanda community in Bihar. Ali Anwar Ansari, associated with the Pasmanda movement, said that in 2009, he had raised this issue in the Rajya Sabha, but at the time, no member of Parliament supported it.

“Lalu Prasad Yadav, Sharad Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav raised it in the Lok Sabha in 2010. BJP leader Gopinath Munde also supported it. And the UPA accepted our demand, but it did not progress,” Ansari said. “If the caste census is done correctly, then the politics of communal polarisation will be blown away.”

Also read: Don’t limit caste census to Hindus. Include tribals, Dalits of Muslim, Sikh, Christian faiths

A great ‘leveller’

Political analysts are of the opinion that after the census—and if the results are published—different power centres will emerge in society, which will work as pressure groups.

“It will bring new energy to the politics of identity. Caste equation and caste-based problems cannot be sidelined in Bihar. They need to be recognised,” said Prof Sanjay Kumar.

Drawing from the 1931 caste census, the Mandal Commission concluded that OBCs comprised 52 per cent of the country’s population.

Forward caste groups in Bihar, especially Brahmins and Bhumihars, are worried.

“Demand for reservation will intensify. The forward castes have already been marginalised. Our situation will worsen after the caste census,” Mishra from Saharsa said.

And the BJP central leadership is restless. “The numerically smaller OBC and Dalit castes have played an important role in the BJP’s electoral success under Modi,” Vikas Kumar said.

Lokniti-CSDS data shows that in the 2009 Lok Sabha election, the BJP got 22 per cent of OBC votes, which increased to 44 per cent in 2019. According to Vikas Kumar, as every party is engaged in the politics of OBC, enumerating and collecting accurate data is important.

In 2017, a four-member commission headed by Justice G Rohini was constituted to identify sub-castes within the OBCs. But its tenure has been extended 13 times, the last time in January for a period of six months.

DM Diwakar, former director of A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna, pointed out that members of many castes are not in tune with the drumbeat of development reverberating across the state and country.

“Many castes are becoming extinct. There is not much information on castes like Pamaria and Malha. If the data is not available, development will not happen,” he said.

There are fears that this will become another Mandal moment—a polarising factor in electoral politics that shaped and defined north India for three decades. But Vikas Kumar dismisses such fears with a simple question.

“There hasn’t been a caste census in the last 70 years. Has this dampened caste politics?”

(Edited by Prashant)