Ameena remembers the evening her husband climbed onto the roof of the rented room she was taking refuge in and threatened to kill her if she didn’t seek a voluntary divorce or khula. After years of abuse and threats, she finally approached the Shaheen Women Resource and Welfare Association in Hyderabad’s old city.

But that’s khula. The non-profit has not received a single case of instant or triple talaq, or talaq-e-biddat ever since 2019, when the hugely contentious ban on the practice was enforced by the Narendra Modi government.

Instead, its office is now full of women like Ameena seeking a khula divorce, exposing what a section of lawyers and activists call a “flawed legislation”.

“It’s a growing and worrisome trend,” says Jameela Nishat, founder of the non-profit, which has recorded a rise in cases of women being tortured physically and mentally by their husbands to such an extent that they are forced to take the khula route of separation. Many in the BJP and the Modi government say the transformative ban on the regressive practice of triple talaq would reduce centuries-old injustice and torture of Muslim women. Instead, many women in Hyderabad are experiencing just the opposite. In an ominous affidavit in the Supreme Court against the ban on short-cut divorces, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board had in 2017 argued that it might force Muslim men to resort to murdering their wives or burning them alive.

The move to criminalise triple talaq was heralded progressive by some, but hurried and ill-conceived by many others, including AIMIM MP Asaduddin Owaisi.

“We have seen many cases where the women were tortured so badly that they wanted to get out of the marriage even without taking their meher,” says Nishat. ‘Meher’ is an obligation—cash or any financial assistance that is agreed upon at the time of the Islamic wedding, which the husband has to pay the wife—either at the time of the wedding or later.

In 2017-2018, Nishat’s organisation dealt with 38 talaq cases and just four khula cases. The following year, it handled 32 such talaq cases and only three khula requests. But suddenly, in 2019, the number of Khula requests shot up to 24, while there were only three talaq cases. And from 2020 till March 2023, there have been zero talaq cases, but 62 khula requests. This trend is also reflected in the increasing number of khula certificates issued by the Waqf board in Hyderabad during the same period. In the one year between 2021 and 2022, it had increased by around 35 per cent.

Fearing legal consequences of pronouncing triple talaq, a section of men are pushing their wives to take the step.

“They (the women) come to us saying humara khula karwadho,” Nishat told ThePrint.

Also read: Unnao teen watched her rapist celebrate bail. Then he burnt her home, threw her son in flames

Finding new ways to torture

It’s what happened to Ameena (26), and now to Zainab Fatima (24) who bears the scars of a marriage suddenly turning violent.

On a hot summer day, Zainab waits her turn at the Shaheen office in Hyderabad’s old city. Covered in a burqa, her fists are clenched as she nurses her left hand. Her husband had poured boiling milk on her. She refuses to file a police complaint, but has approached the organisation. She wants a divorce. The abuse started in 2020, two-and-a-half-years after she got married, and a year after triple talaq was banned.

“The first time he hit me was when I talked back to him in an argument, it has been like that since then. On several occasions, he says he wants to leave me and also suggested in 2021 that I file a khula, but I refused. The situation got worse after that,” says Zainab.

Ameena’s husband, too, is wary of violating the ban on the triple talaq practice. If found guilty, a man can be sentenced to three years in jail. He wanted to marry another woman in 2018. She opposed it. That was also the first time he slapped her.

“He was scared that I might go to the police and get a case booked. So, he started pushing me to file a khula. I refused, and moved out of the house to live alone. He didn’t let my children come with me,” says Ameena, who finally went ahead with the process.

Most of the women who approach Shaheen association for help are from the older neighbourhoods of Hyderabad. But the organisation also handles cases from different parts of the state and even neighbouring Bidar in Karnataka.

And then there are instances when men have demanded money to sign the khula papers.

“The government announced a ban thinking it would cut down on instant divorces, but men are finding a way anyway. What’s left for women then?” asks activist Lubna Sarawath.

With lack of support from family members and empathy from the quazi’s office, the women find themselves fighting this alone.

Also read: Char Dham Yatra to be bigger than ever but Joshimath residents still sleep in animal shelters

The reconciliation trial: Waqf to family

When Zainab first approached the qazi’s office seeking a khula and complaining about the domestic violence, she was asked to “adjust”.

“Do you complain when your husband loves you a lot, then why not tolerate a little beating also,” she claims the qazi told her.

After three such ‘counselling’ sessions at the qazi’s office, she approached the Shaheen Women Resource and Welfare Association.

Organisations like Shaheen do not officiate divorces. They just act as a mediator between the applicant and a formal body like a qazi’s office. And it’s not the only place a woman has to go to after she initiates khula.

Before seeking a khula—and even talak when it was legal—the husband and wife have to go through several reconciliation attempts and discussions with families and religious heads.

When these fail, they approach a qazi’s office seeking a formal separation and written proof. This proof is then submitted to the Telangana Waqf Board, with the woman seeking an official certificate of separation. There are 100 government-appointed qazis who act as administrators of the law, operating across the state.

But not every divorce officiated by the qazi ends up at the Waqf board, although it is supposed to. Barely 15 per cent of couples who receive the certificate go to the Waqf board office, says a source from the Waqf board. The rest carry on with their separate lives.

Last year, the Telangana Waqf Board issued 350 khula certificates for applicants across the state, a significant rise from the 260 it had issued in 2021. And in 2020, it was 25 per cent lower than the previous year, says a senior official from the Waqf board who did not want to be named.

There’s a similar trend in applications as well. “We’ve seen a 50 per cent drop in talaq applications but there is a corresponding increase in khula applications,” the senior Waqf board official told ThePrint.

Although Khula is a woman (voluntarily) filing for a divorce, it still requires the husband’s consent to be processed, says Jameela.

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Telangana is confident that the triple talaq ban has reduced cases of injustice and torture against women.

“If women are forced or tortured into taking a khula, they still have an option to go to the police. This applies to every community. But what the ban has done is put a stop to instant talaq, where men could just abandon women,” says former MLC and senior BJP leader, Ramchander Rao.

Up until 2021, within Hyderabad city’s limits alone, the police registered more than 50 cases of triple talaq being illegally invoked. A significant chunk was reportedly filed by women who were married to people outside of India. In February 2023, a woman alleged that her husband had pronounced talaq over the phone.

But like any other law in India, the triple talaq law too is seeing misuse even if such cases are fewer in number. Activists have come across instances of wives holding the ban over their husbands’ heads threatening them with police cases.

“I have had cases where the women have had an extra-marital affair, but when the husband wanted a divorce, they threatened to file a police complaint,” says Hyderabad-based social activist Khalida Parveen.

But counselling is the first step. “We try to resolve the dispute rather than heading to a khula,” Parveen adds.

BJP members are also aware of rising khula requests.

“But there are still legal ways of approaching the matter. At least, they’re not being abandonded like before,” says Rao, who is also a lawyer.

Also read: Indian PhDs, professors are paying to publish in real-sounding, fake journals. It’s a racket

Law and the question of empowerment

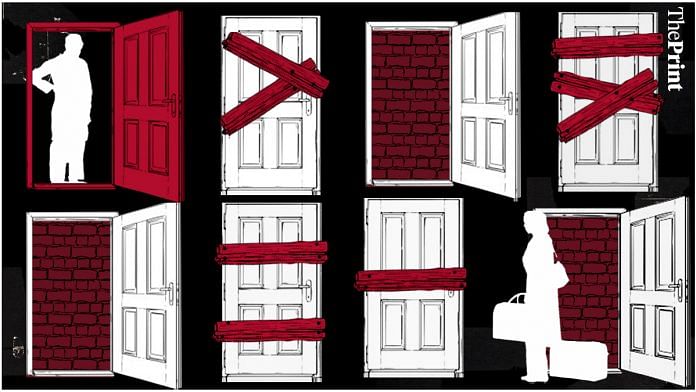

Many of the women who are knocking on the doors of the Shaheen association and other such organisations have simply been abandoned.

The 2017 Supreme Court ruling setting aside talaq-e-biddat (triple talaq) was hailed by human rights organisations and Muslim women such as Shah Bano who was among the petitioners. It was seen as a step towards women’s empowerment.

In a majority 3:2 judgment, a five-judge Bench termed triple talaq as unconstitutional, and declared the practice illegal stating that it violated fundamental rights under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

Two years after the verdict, the Bharatiya Janata Party-led NDA government pushed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act 2019 through Parliament, criminalising this form of talaq.

But nothing has changed on the ground, there is hardly any impact of the ban, says Amjed Ullah Khan, spokesperson of Majlis Bachao Tehreek (MBT), a political party in Telangana.

“It is not like we’re seeing a decrease in divorces. Men have found a way to leave women,” he says.

What the certificates, cases and khula applicants don’t show is the rise in the number of women who have been abandoned by their husbands

“In my praja darbar [public grievances session], I see 10-15 cases a day of women complaining that their husbands have left them and vanished,” says Amjed Ullah Khan. These men fear the ramifications of the triple talaq ban, but don’t want their wives to take a khula. So they abandon their wives, keeping them in marriage—and in limbo.

It is not like this never occurred before. “But there has been an increase since the ban. And this is not specific to a particular area in the city or a certain economic section of people, I am seeing these cases from all kinds of families,” Khan insists.

Ego comes into play here, says Zehra Jabeen, of Shaheen.

“The wife first disagrees over issuing khula, and when she does, they (the husbands) do not want to and hold her back.” says Jabeen.

Three most practised Islamic ways of divorces are ‘Talaq-e-Hasan,’ ‘Talaq-e-Ahsan,’ and ‘Talaq-e-biddat.’ However, the form of practice varies when it comes to different sub-sects within the community and not all forms of talaq are accepted by all communities, there are exceptions. Talaq-e-biddat is illegal.

And contrary to the popular narrative, not all Muslim women supported the ban.

Also read: No caste without code—Bihar is counting and writing a new identity politics

The missing ecosystem

Among the many who opposed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, calling it a flawed legislation, was activist Lubna Sarawath.

“What does the Act offer for women? It is a piece of legislation thrown at people with absolutely no solutions for women or the situation,” says Sarawath. She argues that it offers little protection to women, and instead has pushed them into further misery.

“The Supreme Court order quoted verses from the Quran on how a situation (where misunderstanding between a couple occurs) should be handled. Has the government, as part of the legislation, established a counselling cell or allow any legal aid for women to come out of this situation? Nothing,” she adds.

Sarawath, who has been working for women’s rights protection for at least over a decade, claims that the qazis are encouraging women to opt for khula because they don’t want to get tangled in the process of a talaq, fearing the criminalisation of the practice.

Telangana Waqf Board chairperson Mohd Masiullah Khan is aware of this situation.

“It has come to our notice,” he says. But the body has yet to announce a plan to tackle this. For now, religious heads and leaders are reportedly being asked to “counsel” Muslim men in their community.

And like the Muslim Personal Law Board, Khan too pointed out that slow wheels of justice with the innumerable court hearings that can go on for years does little to encourage people to take the legal route—no matter what BJP leaders may say.

“The fault is also with the Indian courts and judiciary. If one case of separation takes years to settle, why would people go there to settle it? They would prefer to settle it amongst themselves,” says Khan.

Also read: No caste without code—Bihar is counting and writing a new identity politics

Life after khula

Today, 28-year-old Najma is slowly putting together the pieces of her life after she received a khula certificate. Her husband forced her in to file khula. For the first time in her life, she is financially independent—and alone.

Barely 15 per cent of the women who are being abandoned or divorced are financially independent, says Jameela, a view that other activists agree with.

For Najma, the first challenge was to find a place for herself.

“No owner was ready to give room to a single woman,” says Najma, who prefers to stay in old Hyderabad, especially in areas which have a dominant Muslim population.

Her maternal family refused to welcome her back into the home, a consequence of social stigma. When it was time for her to earn and support herself, she realised that she had been a dependent all her life — as a child, a daughter and a wife.

She did not even go to school and did not know how she would support herself. She also says she was ‘offered’ by a few men in her colony that they would accept her as one of their wives. Instead, she works as a domestic worker.

“I still struggle while I sleep alone each night. All of a sudden, I have no one with me, not even my family. My parents wanted me to be with my husband, no matter what, and I did not oblige,” she says.

The initial months were especially tough.

“It was horrible. I am not any happy now, but I am certainly not waking up scared of being beaten to pulp”.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)