Ghazipur: The stench in the air around Ghazipur dairy farm is putrid. Tin sheets in this colony of cowsheds and haphazard buildings prevent the garbage at Delhi’s oldest and largest landfill from spilling into homes. Since last year, though, cranes have been rolling up and down the garbage mountain—nearly the size of Qutub Minar—digging, dragging, and tearing into it. But time is running out.

The Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) has until December 2024 to flatten the Ghazipur landfill. Two other dumping grounds, Okhla and Bhalswa, need to be cleared by May 2024. The three sites occupy over 200 acres of land.

India’s cities can no longer ignore the stench, illnesses, pollution, fires, and accidents at landfills. They are the underbelly of a country that marches to the drumbeat of unplanned and unprepared urbanisation.

Pressure to clear the landfills has been mounting. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) and the central government have set deadlines to clean cities and towns of their piling waste. In November last year, MCD hired three private companies to scientifically process the waste and reuse the fractions.

Since then, contractors have rolled in heavy machinery like trommels and ballistic separators onto the trash piles. The unrelenting stench has not dampened confidence.

“We have processed 13 lakh metric tonnes [of waste] in eight months at the Okhla landfill. We are confident of completing the job within the deadline,” says Ramakant Burman, managing director, Greentech Environ Management Pvt. Ltd.

But, experts are sceptical of the tight deadlines. Flattening the land will likely take many more months before it could be reused for other purposes. Every towering mountain of garbage rests on legacy waste—old trash collected and now decomposed. Managing this is the first hurdle. Then there is the lack of disposal infrastructure for the fresh waste generated in the city. This makes the task more challenging.

I don’t know how garbage started getting dumped here. But since then, people keep falling sick. Our ACs, fridge, LCD, all stop working after a year or two

—Beg Raj Singh, a residents of Rajbir colony next to Ghazipur landfill

“The dumpsites cannot be cleared at the rate at which the legacy waste is currently being processed. Additionally, different machines used at various sites have varying capacities to process the waste,” says Richa Singh, programme manager of the solid waste management team at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a think-tank. “Although it is a positive step, the deadlines are quite ambitious.”

Ticking time bombs

Landfills have been functioning beyond capacity for more than 15 years. It is decades of neglect and a narrow understanding of waste disposal that has brought us to this stage, explains environmentalist Bharti Chaturvedi.

Waste has been dumped at Ghazipur since 1984, at Bhalswa since 1994, and at Okhla since 1996, reaching their capacity in 2002, 2003, and 2010, respectively.

“From the 1980s onwards until about 10 years ago, the narrative was how to collect and dump waste efficiently. There was no thought about environmental issues. No one cared what happened to the landfills,” said Chaturvedi, director of the nonprofit Chintan Environmental Research and Action Group.

We have processed 13 lakh metric tonnes [of waste] in eight months at the Okhla landfill. We are confident of completing the job within the deadline

—Ramakant Burman, managing director, GreenTech Environ Management Pvt Ltd

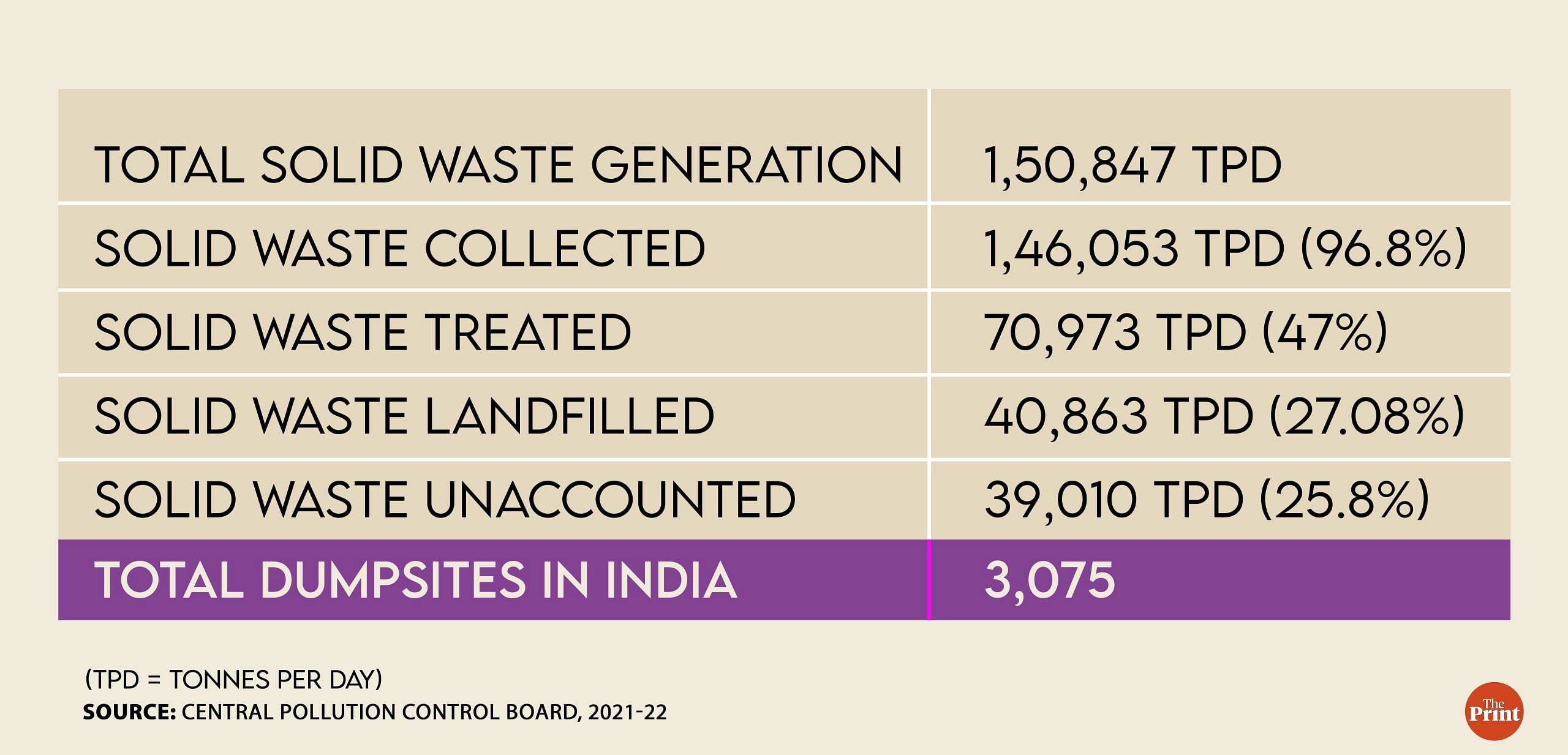

Things were no different in other Indian cities and towns. According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB)’s 2021-22 data, there are 3,075 dumpsites in the country. Out of the total solid waste of 1,50,847 tonnes per day generated in a year, 27 per cent (40,863 tpd) reaches the landfills.

“Earlier, there was no processing [treatment of waste]. We were just waiting for the thing to collapse on its own. It’s dangerous because methane can explode on its own and catch fire. We have basically been living on a time bomb and we are beginning to recognise it only now,” says Chaturvedi.

Beg Raj Singh, who lives in Rajbir colony next to the Ghazipur landfill, remembers a time when Teetar trees grew in the area. It’s been his home since 1987, and over the years he’s seen the mounds of garbage grow and the trees die.

“I don’t know how garbage started getting dumped here. But since then, we have had so many issues. People keep falling sick. Our ACs, fridge, LCD, all stop working after a year or two. I don’t know which gases are released [from the waste],” he says.

In 2017, a mound exploded, perhaps because of the methane trapped in its bowels. Its impact could be felt even a kilometre away. “Many people died. Rumour was that the site would be cleaned soon. But nothing happened.” Singh added.

The efforts to clear the land of waste has shown results in many cities. In Andhra Pradesh’s Vijayawada, a 65-acre dumpsite was cleaned in 2019 using biomining. Close to 90 per cent of the waste was utilised, and a waste-to-compost facility, plastic waste management facility, and a construction and demolition waste plant came up on the site. It is the largest dumpsite land reclamation project in India.

Similarly in Gujarat’s Vadodara, a 14-acre dumpsite was cleaned and replaced with a construction and demolition waste facility and a plastic waste processing facility.

Delhi is expecting similar outcomes. To speed up work at the three sites, where each contractor has to clean 45 lakh metric tonnes of waste, the MCD has been planning to release new tenders for clearing an additional 20 lakh metric tonnes of waste at each site. “The area will be divided among multiple contractors. This will speed up the process and we will be able to meet the deadlines,” an MCD official said on the condition of anonymity.

The plan, though, is stuck in administrative hurdles.

Despite the high-speed work, residents near the landfills find it hard to trust the municipal corporation to clean the giant garbage mountains.

“Work has been going on for the past 24 months, but the height of the landfill is not reducing. Machines go up and down, but we don’t see any results. We will believe only after the garbage has been fully cleared,” says Anil Kumar, who runs a workshop near the Ghazipur landfill.

Garbage on primetime debate

The high-pitched MCD election in Delhi last December became a battleground for political parties vying for control of one of the world’s biggest municipal corporations (second only to Tokyo). A common issue topped their agenda—garbage.

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) made landfill clearance a priority among its “10 guarantees”. The BJP pledged the same in its Vachan and Sankalp Patras.

AAP leader Atishi launched the ‘Kude Par Jansamvad’ campaign, and Delhi Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia called the landfills “garbage of the BJP”, vowing that AAP would clear them in five years if given control of the municipality. Sisodia accused the MCD, under BJP rule, of simply relocating garbage instead of properly disposing of it. On the other hand, the BJP accused the AAP of not releasing funds for landfill cleanup.

“For the first time in the history of Indian television, landfills were discussed on primetime debates,” says Singh. “People were saying they will clean the site in a year, but no one knew how it would be done.”

Like cities, landfills have spread their tentacles and encroached the land around them. Unauthorised colonies of rag pickers and people dependent on trash for their livelihood have sprung up around the Ghazipur, Okhla, and Bhalswa sites. In these settlements, people separate recyclable waste from kitchen waste. Pungent smell, garbage decaying on roadsides, and illnesses have become a part of people’s lives.

In addressing the challenges of waste management, it is crucial to consider the impact of decentralized systems that empower communities to take charge of their waste. This approach not only enhances efficiency but also fosters a sense of responsibility among residents.

The political mudslinging over mountains of garbage persisted after AAP won the municipal election in December 2022, ending 15 years of BJP control.

An official at the LG Secretariat, who did not want to be named, told ThePrint that work on the landfill sites started “soon after LG [Vinai Kumar] Saxena took office in May last year”, inspecting the three sites five times over a year.

While AAP blamed the BJP for letting the garbage accumulate, the BJP accused the AAP of stalling work since taking over the municipality.

“Nothing could be far from the truth if the Aam Aadmi Party tries to take credit for clearance of landfill sites. The speed of disposal was much faster before than it has been since March 2023. At the current speed, the three sites are unlikely to be cleared even by December 2025,” said Virendra Sachdeva, Delhi BJP president. He added that Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal himself admitted that the work is running far behind schedule.

Earlier this month, CM Kejriwal inspected the three landfill sites. He declared that while Bhalswa has processed 18 lakh metric tonnes of waste until September, Ghazipur is far behind the target, having cleared only 5.23 lakh metric tonnes against the target of 15 lakh metric tonnes.

“Ghazipur…has around 80 lakh tonnes of garbage. The pace at which waste is being removed…is significantly slow,” said Kejriwal, The Hindu reported.

In Andhra Pradesh’s Vijayawada, a 65-acre dumpsite was cleaned in 2019 using biomining. It is the largest dumpsite land reclamation project in India.

Data from the LG’s office reveal that a total of 125 lakh metric tonnes of garbage were disposed of between May 2019 and May 2023, reducing the height of the three sites by 15 to 20 metres each.

ThePrint reached out to the Delhi government and Mayor Shelly Oberoi through call and text for comments, but did not receive a response. The copy will be updated when they do.

Targets and deadlines

The pressure to clear the landfills began mounting much before political parties incorporated it into their election mandates.

In 2019, the NGT ordered the CPCB to clear all landfills in Indian cities and towns. That same year in February, the CPCB released guidelines on biomining of old waste at dumpsites. Many individual cases were also filed with the tribunal concerning the pollution caused by dumpsites. Additionally, the Centre’s Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) 2.0 set 2026 as the deadline for clearing all landfills in the country.

But an MCD official from the Department of Environment Management System (DEMS), who did not want to be named because he is not authorised to talk to the media, told ThePrint that actual work on the landfills started only late last year.

“Before the contracts were given in November 2022, MCD used to hire trommels and work was done inconsistently. But this became more structured after the tenders were allotted,” said the official.

Private contractors explained that prior to 2019, there was no clear direction on how to clean landfills. “The political will was also missing. Two years after the 2019 NGT order were wasted because of Covid. Biomining could properly start only in 2022 when contracts were given. And the work is visible now,” said Burman, whose Greenwich Environ is responsible for cleaning the Okhla dumpsite.

At the landfills, large machines are stationed on the garbage piles. Cranes claw at the trash to release trapped methane, and the garbage is loaded into these machines, which function as sieves. The segregated waste is largely bricks and stones (construction and demolition), fine soil-like material (inert), and plastic waste (refuse-derived fuel or RDF). These materials are then loaded onto trucks, weighed, and transported to their respective destinations.

While the soil and bricks can be used in the construction industry and for filling low-lying areas, the plastic waste can substitute coal in cement factories and waste-to-energy plants.

A May 2023 press note from the office of the LG mentioned that during the last quarter, the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) “lifted inert waste for its project at Karala Majri, Burari, Kundli, Holambi…for NTPC Eco park and for Faridabad Mithapur”. The note added that while construction waste had been sent to sites at Khampur, Keshav Nagar, Burari, the plastic waste was used by JK Cement in Chittorgarh, Ultratech Cement, and paper mills in Western Uttar Pradesh.

As per MCD data, as of November 2022, the estimated combined waste from the three sites, as per a drone survey, exceeded 200 lakh metric tonnes.

Meeting the targets

The current contractors, for all their optimism, are also facing operational hurdles.

At the Okhla site, the deployed machines have the capacity to process up to 20,000 metric tonnes, which is double their current processing rate. However, due to the site’s location, at the centre of a bustling industrial area, they are unable to transport all the processed fractions to their respective destinations, which delays their work.

“Even if we process more, we won’t be able to store new residue unless we transport [the processed fractions] out. Our trucks get stuck in traffic,” explains Rajkaran Singh, deputy general manager, Greentech Environ.

At the Ghazipur landfill, contractor Sudhakara Infratech refused to speak to ThePrint and didn’t allow entry to the dumpsite citing security reasons.

Richa Singh from CSE explains that disposing of the residue after processing waste is a critical aspect of biomining, which is often neglected. “Biomining is not just about the treatment of waste; it is about the scientific disposal of the recovered material. This is most critical. It should not be dislocated pollution where waste is being extracted from one site and deposited somewhere else,” she said.

Delhi’s limited capacity to process tonnes of daily waste is also hampering the flattening of the landfills. On one hand, legacy waste is dug out; on the other, trucks full of fresh, mixed waste continue to arrive at the same dumpsites. To divert waste from landfills, the MCD has four functional waste-to-energy plants in Tughlakabad, Ghazipur, Okhla, and Bhalswa. But these can only process up to 8,500 metric tonnes of waste daily, while the city generates about 11,000 metric tonnes.

“We do not yet have the capacity to process all the waste,” an engineer working at two of the waste-to-energy plants explained.

Moreover, segregating waste at the source has remained a distant dream for Delhi. Mixed waste reaching landfills further adds to the pollution.

At dawn, MCD trucks laden with fresh waste arrive at the dumpsite. Children with gunny bags slide in and out of the cracks between the tin sheets covering the landfill. The skies are filled with eagles flying above people’s heads. Yet, at Ghazipur, waste isn’t dumped only inside the landfill; the streets, markets, and residential colonies are littered with flies buzzing around discarded packets of chips, rotting vegetables, and sludge. People crossing the site hasten their pace and cover their noses with dupattas and handkerchiefs.

The solution lies in preventing wet waste from reaching landfills—a goal only possible with the involvement of people who call Delhi their home. Experts propose a decentralised system where composting becomes mandatory, and resident welfare associations play a crucial role.

“The government must build capacity with the RWAs in terms of money and space so that they can compost their own waste,” says Chaturvedi.

Making Delhi truly clean requires the active participation of its residents. “Waste management is a shared responsibility; it is not the sole responsibility of any one person or political party,” says Singh.