Kolkata: Bengal’s perennial biryani wars — long-dominated by legacy heavyweights like Aminia and Arsalan — have found two new contenders. In food-rigid Kolkata, this is no small disruption. In a sleepy Kolkata railway suburb, Dada Boudi Hotel has turned its slow-built following into what loyalists now call a distinct “Barrackpore-style” biryani. In posh south Kolkata, Hanglaatherium is pushing the same iconic dish through café culture and social media virality. Two restaurants, two methods. The city’s biryani obsession remains but the playbook has changed.

Kolkata’s relationship with food borders on the possessive. Yet over the past decade, a staple favourite like biryani has broken the pattern. Newer players are drawing devoted followings by altering how biryani is presented, marketed, and consumed.

Once a modest railway-side Hindu hotel serving Bengali thalis to blue-collar workers in the 1960s, Dada Boudi Hotel has reinvented itself slowly, almost stubbornly, over decades. Its biryani, once an experiment priced at Rs 11, is now devoured by 2,000 diners a day at its seven-storey restaurant in Barrackpore, now one of Bengal’s busiest biryani destinations.

On the city’s outskirts, biryani mania looks like patience, banana-leaf plates, giant mutton pieces and no-frills seating.

But in south Kolkata’s posh Jodhpur Park, nearly 30 km away, Hanglaatherium represents a different kind of ascent. Dubbed a new age ‘biryani café’ by founders, the eatery began as a 5ft-by-10ft kiosk serving plates of aromatic, ghee-heavy biryani. Customers are often drawn to the cafe by reels. Some come specifically to meet the owner, Sunando Banerjee — the viral “biryani man” of Instagram.

If Dada Boudi’s rise was powered by memory and word-of-mouth, Hanglaatherium’s is propelled by visibility and virality. But in Bengal, biryani has always meant more than business.

“This new biryani fanaticism is not regional. It accepts dishes from elsewhere, and is not religious or chauvinistic when it comes to food. Biryani is essentially a Muslim dish, but the spirit of Bengal is such that food there is not seen as Hindu or Muslim. This is important today when food is dividing people,” senior food columnist Vir Sanghvi said.

While much of India debates whether Lucknowi, Hyderabadi or Kolkata biryani is superior, Bengal’s argument has turned inward, much like football: which local biryani deserves loyalty now.

The Dada Boudi spectacle

At exactly 3pm on a warm Wednesday, two serpentine queues snake out in a busy market area outside the railway station in Barrackpore, much like a crowded scene outside a Durga Puja pandal. Up close, it is something far more ordinary: people waiting for biryani at Dada Boudi Hotel, their impatience rising with the smell of mutton and ghee drifting out of the building.

“Another 20 minutes and I will be eating a big juicy piece of mutton,” Minu Mandal said with one hand on her belly, as the queue crept forward.

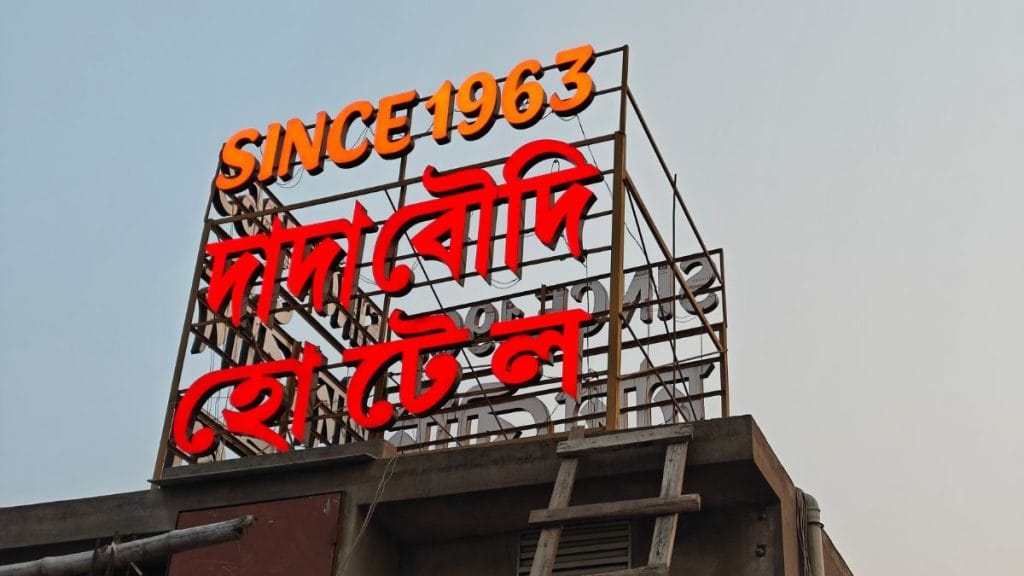

Established in 1963 by a couple, Dada Boudi (translating to brother and sister-in-law) became a widespread sensation in the last decade, with food vloggers increasingly featuring the restaurant, and media writing about eatery’s rags-to-riches story.

Dada Boudi Hotel started off as Janata Hindu Hotel in the 1940s serving traditional Bengali thalis to railway workers, rickshaw pullers, drivers and porters who passed through Barrackpore station.

“When my parents ran the restaurant, bank and government officials came too. They would tell my mother to save them a bowl of her chicken or mutton preparation,” said Sanjib Saha, who manages the business with his son, Subham.

Sanjib’s mother took charge of the kitchen in the 1960s.

In the early 1980s, Sanjib and his friend Kamil Khan decided to introduce biryani at the eatery.

“There were hardly any biryani shops here those days. After much thought, we included in our menu a plate of chicken biryani. We priced it at Rs 11 per plate,” Sanjib said.

The first three kilos of biryani, however, found no buyers.

“We had to throw it all away in the drain,” said 58-year-old Sanjib, pointing to a ditch across the road. The disappointment still shows on his face.

They didn’t lose hope and cooked again the next day. This time, the pots emptied.

The dining space has since expanded from a 64-seater to nearly 400 seats. Three decades later, Dada Boudi operates two outlets in Barrackpore and plans further expansion outside the town.

Biryani-ready

At Dada Boudi, preparations for the day begin at 7 am. Meat is inspected, groceries sorted and multiple chulhas lit under massive handis.

Fresh batches of biryani are cooked throughout the day inside the sprawling kitchen, and every few hours a tempo unloads new vessels to replace the emptied pots.

Subham Saha, the proprietor, says quality is key.

“We are extremely selective about the quality of mutton we use for our meat. The spices are also carefully sourced,” Subham Saha, 28, the proprietor of Dada Boudi, said.

The restaurant produces 300-400 kg of biryani daily and turnover touched Rs 80 crore last year, up from Rs 15 crore in 2020-21.

Kamil Khan continues to train cooks in what the owners describe as the restaurant’s signature method of cooking biryani, a family recipe.

A plate of mutton biryani with the non-negotiable potato costs Rs 360 and chicken biryani is priced at Rs 260.

“I like this place because they ask you which piece of mutton you want in your biryani,” said Pihu Kundu, finishing an early dinner. Her father, who has been a regular since the 80s said, “Quality has dipped now, but it still is very good,” he said.

Kolkata’s biryani culture

For decades, Kolkata’s biryani war had only two sides. You were either loyal to a legacy name like Aminia or Arsalan or you were wrong. Generations in the city grow up swearing allegiance to a single mishti (sweet) shop, a single fish market, or a single biryani eatery.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, biryani moved from royal kitchens to street corners. With meat being expensive, migrant cooks from Uttar Pradesh sold sweeter Awadhi-style variants with potato and egg, making the dish affordable and ubiquitous. Today, a plate can cost Rs 70 at a roadside eatery or Rs 500 in a polished dining room.

“The whole biryani craze dates back toward the end of the 1960s. I started living there (Kolkata) in 1986, and biryani had just become popular. Now it’s like the only dish that matters. Bengalis will brag about it and will say the only biryani that matters is Calcutta biryani. They do not point out that Calcutta biryani is basically a poor man’s version of an Awadh biryani,” Vir Sanghvi said.

Kolkata biryani is said to have been created by Nawab Wahid Ali Shah who was banished by the British to Calcutta in 1856. Unable to afford meat, the local cooks replaced the meat with perfectly cooked golden brown potatoes.

“Although there is meat now, potatoes remain an important part of the dish,” reads the Bloomsbury book of Indian Cuisine (2023) on biryani’s origins.

Also Read: How basic Bengali food became a premium experience at Sienna

The eateries slowly expanded and the city got Aminia, one of its most-loved biryani brands, that started its operations almost 100 years ago. Now it’s one of the go-to places for biryani with multiple outlets across the city and country.

Arsalan, another crowd favourite, is much younger in comparison.

The initial blueprint was a family biryani restaurant with ample seating and good interiors. The brand, founded to fill the gap of Mughal restaurants in the city, got its first restaurant in 2002.

India Restaurant, Royal India, Shiraz Golden restaurant, and Nizam’s are other big players in the game, scattered across the city and ever-expanding, with loyal customer bases for years. Now, newer players have disrupted that binary.

The south Kolkata biryani

Bored with their 9-5 monotonous jobs, three friends decided to sell biryani post-work. That’s how Hanglaatherium, a new-age biryani ‘cafe’, was born 15 years ago.

“It was actually a sort of alcohol-induced declaration when I told my friends that I want to open a biryani place. The next day during an office presentation, my friend called and said he had actually booked a place. That’s how Hanglaatherium started,” said Banerjee.

Haangla means glutton in colloquial Bengali. The cafe gets its name from Sukumar Ray’s story ‘Heshoram Hushiyarer Diary’ (1923), where a character called Hanglaatherium is obsessed with food.

The cafe started as a 5ft-by-10ft kiosk with doodles of biryani on its red and white walls, a departure from the grand Mughlai restaurants of the city. The concept was simple: instead of taking home a parcel, sit and have a chat over a plate of biryani.

“In Kolkata, we usually pack biryani or sit at a restaurant. But we also love our cafes. I wanted to bring the two together. Why not have a cafe for biryani, like for coffee,” Sunando Banerjee, who started the restaurant with his two friends Avijit Majumdar and Piyali, said.

Their offering was still the light, aromatic Kolkata biryani with the humble potato but they had a simple rule: ingredients have to be healthy.

“Whatever we cooked, I would also take it back for my then 5-year-old son. That’s why I was adamant about not using vanaspati (solidified vegetable oil) in my biryani. We use ghee, the healthier alternative. It does not leave you with a heavy feeling in your stomach,” Sunando said.

Hanglaatherium’s head chef SK Razzaque, who has previously worked at The Park and Kareem’s, leads recipe management, along with Banerjee, across all six Hanglaatherium outlets.

The first batch starts cooking at 11 am. The mutton is fried, rice is boiled and then the layering starts with onions, yoghurt, ghee, and of course, potatoes.

Hanglaatherium uses only the jyoti or chandramukhi variety, chosen to ensure uniform potato size in every serving. They also sell other items like Delhi-inspired Aslam butter chicken and nihari with a twist.

By 12:30pm, the restaurant opens its doors for both in-house delivery and dine-in.

The restaurant’s popularity surged in the past seven months after Banerjee began producing reels centred on Bengali food humour and customer interactions. He is now viral as ‘the Biryani Man’.

The ‘Biryani Man’

A young woman walks into Hanglaatherium and smiles at the ‘Biryani Man’.

“I love your reels. No other Bengali place does it. So I decided to try the biryani,” said Piyali, who had come from Belgharia, 20 km away.

A loyal Arsalan customer, she said she was willing to switch, at least once, based purely on social media presence and online reviews. Banerjee’s strategy was working.

“The problem with Kolkata is that we do not know how to market ourselves well. Now that I do my marketing, some people say stop making reels and make biryani,” Banerjee said wryly.

The bespectacled man in his 50s bagged his first job at Motorola after completing his Electronics and Telecommunication engineering degree from Mumbai University. But he soon quit, joined a dot com company as a cartoonist, and later did consulting for global retail brands across nearly 50 countries before starting Hanglaatherium. He also got an award from RK Laxman.

Apart from being the co-founder and CEO of the cafe, Banerjee is also the Chief Operating Officer at the marketing agency, Anonymous Digital, which has handled clients like Anjan Chatterjee, founder of the iconic Oh Calcutta chain of restaurants.

Hanglaatherium does everything in-house — from scriptwriting, actors, shooting to uploading across social media.

One reel with over 1.4 million views shows Banerjee offering compensation to a customer who jokingly complains about mutton. Another reel with 1.7 million views presents biryani as the cure for every crisis in a Bengali’s life.

Customers now stop Banerjee and his staff on the street, recognising them from the videos and promising visits.

Beyond the algorithm

While Hanglaatherium has cracked the algorithm, Dada Boudi is content with word-of-mouth publicity and draws people across continents.

In 2017, Craig Hall, the then US Consul General in Kolkata and his wife Meeryung Hall and other consulate members made a trip to the restaurant.

Many want to know the ‘secret’ recipe or be part of the business. But its owners are not keen.

“A lot of places in Kolkata get viral and then shut down because they are unable to maintain quality. So we want to scale up steadily. For us it matters that every customer finishes their plates, unless they are too full to do so,” said Subham.

Their social media traffic is also purely organic.

“We do not invest a lot of money in promotions. Our biryani is our PR,” he said.

The lull lasts barely for two hours in the evening at Dada Boudi. By dinner, workers move quickly through the aisles, carrying plates in steady succession.

Floor managers scan tables and usher in waiting customers in seconds.

Sanjib and Subham walk the floors continuously, checking plates, and making sure everyone has had their fill.

While the place is loud, tables usually fall silent when the biryani arrives, almost as a mark of reverence.

“In an era when people don’t even watch a 15-second reel, customers wait for half an hour to eat our biryani,” Subham said.

(Edited by Stela Dey)

My thoughts on this are that the biryani at Kathi Junction’s Newtown branch is the best one in Kolkata right now.

Your selection for contenders for best barrackpore biriyani should have been more and should have involved dada boudi restaurant along with dada boudi hotel and D bapi restaurant. Also in contention for Kolkata Biriyani not only Arsalan, there should be mentions of name Shiraz,Zam Zam as well. But for the undisputed kings of biriyani title, it’s between Dada Boudi Restaurant(not Hotel) and D Bapi(Barrackpore branch)