Tral: The call to return came after 32 years, in 2022. Ramesh Bhat was made president of his village shrine in Nowdal, Tral—the same village he had fled as a teenager during the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits.

“It was an emotional moment for me. When I saw the shrine, it was in ruins. That’s when I decided I would revive it and not only make it functional but grand,” said Bhat, who was attending Kheer Bhawani mela, Zyestha Asthami festival dedicated to Kashmiri goddess Ragyna Devi, in Anantnag.

The shrine lay in despair. The Shiv Ling stood neglected. A thick layer of moss had taken over the water body around it. Wild grass had sprouted through the cracks in the stone flooring.

Three years later, a large, unpainted structure has come up. A Hawan Kund has been built. The next phase of work is focused on building the main temple where the Shiv Ling rests.

Almost three decades after the migration, Kashmiri Pandits are returning to the Valley—not to resettle, but to revive the temples in the neighbourhoods they once called home. It’s a quiet assertion of their existence.

The revival process is remote and online: Through WhatsApp groups, video calls, and online payments. Elections for the temple president are fought online. And the funds are gathered from former residents who are now living in Delhi or Mumbai. On the ground, an army of Kashmiri Pandit PM package employees—who live and work in the Valley—closely monitor the work. These employees are working in Kashmir under former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s Comprehensive Economic Package, introduced in 2008 to facilitate the return and rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits. From Srinagar to Tral to Anantnag, around a dozen temples have been revived in the last five years. Work on several others is underway. However, funds remain insufficient.

Last December, after repeated pleas, the government under the Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museums, J&K allocated Rs 17 crore for upgrading and renovating temples and shrines—based on their historical nature—in the twin districts of Pulwama and Anantnag in South Kashmir.

But that isn’t deterring these residents, who have been scattered for the past 35 years. The revival of these temples is bringing back something more important—a sense of community and identity.

“The restoration of temples is not just about religion anymore. It is the marker of our identity. It is proof that we lived here. And we will return. It is the reflection of Kashmiri society and its pluralistic nature,” said 60-year-old Bhat, who lives in Jammu.

Also read: ‘Modi made our dream honeymoon possible’—couple on board the Srinagar Vande Bharat

The process of revival

The plan to revive the shrine had three stages: Reconnect with the families who once lived in the village, arrange funds, and create a team to monitor the revival.

Bhat was made president by a collective decision taken by a group of Tral residents—most now living in Jammu, and half a dozen still living in Kashmir. An association was formed—the Temples and Shrine Prabandhak Committee, Tral.

The very next morning, Bhat packed his bag and left for his village. Meetings were held at the home of one of the Kashmiri Pandit families still living in the village. Before the exodus, nearly 100 Pandit families had lived in the area. But not all of them were connected anymore.

“It seemed impossible at first. To revive a shrine, a lot of funds are required. You don’t just need a temple — you need a dharamshala, a hawan kund. And given our smaller numbers in the village, how can you even think of starting something like this?” said Bhat.

So began the task of reaching out to the 100 families. The first stop was the government offices, to look for lists of migrated families. Then, they went on Facebook to search for people. Word was spread within the community. A list was formed by asking the connected members to recall who their neighbours were. It eventually led to the formation of a WhatsApp group ‘Tral Residents’.

And then, began the conference calls to discuss the revival. During one call, someone brought up another abandoned temple—this one in the nearby village of Noorpora. Suddenly, the project grew bigger. The responsibility to revive Noorpora’s temple also fell on Bhat’s shoulders.

And the support started pouring in. A Kashmiri Pandit family living in Delhi sent two trucks of cement for the temple. Another family in Mumbai donated Rs one lakh. Few other families in Jammu donated Rs 50,000. And just like that, around Rs 30 lakh were raised.

“It took three years to revive the Noorpora temple. Simultaneously, the work for the Nowdal shrine was started,” said Bhat. Since Noorpora was a temple and not a shrine, it was chosen for revival first—the reason being that it required comparatively fewer resources.

Bhat and family live in Jammu, so an unemployed Kashmiri Pandit was given the task of monitoring the temple’s construction. His candidature for the job matched the three attributes Bhat was looking for. The young man was fearless, strongly built, and capable of fighting back if needed. And it was decided that he would be paid Rs 40,000 every month for the job.

“His work was to visit Tral every day from Srinagar. Stay on the premises till the labourers are working. And update the group with photos and information by the end of the day,” said Bhat.

And last year, Noorpora temple came back to life. It stands under the shadow of a lush green chinar tree. A saffron flag flutters atop the shikhara, high above the temple. The doors are adorned with intricate Kashmiri wooden work. In another corner of the temple premises, construction is underway to build a hawan kund.

The eleven Kashmiri Pandit families still living in Tral now gather at the temple every morning and evening for bhajans and aarti.

“It has given a new meaning to our lives,” said a KP resident who didn’t wish to be named.

But for Bhat, the work is still not done. He is now struggling to gather funds for the Nowdal shrine. The construction has been halted due to the money crunch. He is knocking on every door—J&K Archaeology Directorate, the Lieutenant Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, and even applying for loans.

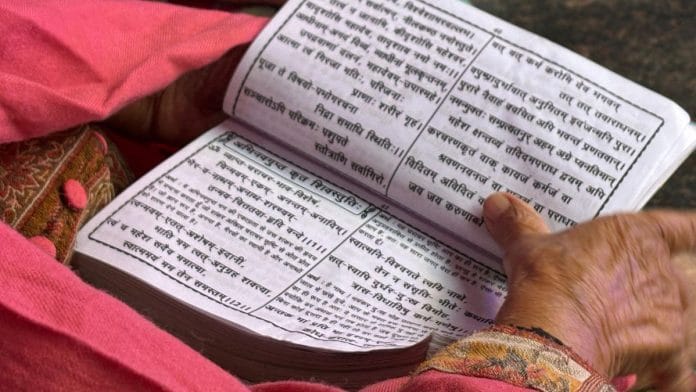

According to the Kashmiri Pandits, the shrine holds greater significance because historically, Amarnath Yatra would be considered complete only after depositing the trekking sticks at this shrine and offering prayers to Lord Shiva. Bhat said that with the shrine’s abandonment, even its history has been wiped out. And now, his phone is filled with snapshots of religious books mentioning the shrine and its connection to Amarnath Yatra. And during his trips to the government departments, he keeps showing them so that the government can help him with the revival.

Along with the restoration projects, new temples are being built within the CRPF-secured areas in the outskirts of the city where PM package employees live.

Building new temples

The temple bell swings as a young girl jumps to touch it. Wearing a bright yellow kurta, Sunny Raina lifts her up so she can ring the bell. Another woman, a dupatta draped over her head, enters with a bowl of kheer in her hands. It is Zyestha Aashtami, Kheer Bhawani mela. It’s the biggest annual festival of Kashmiri Pandits. She places it in front of the goddess, seated inside a mirror alcove.

This temple was built in 2024 inside the quarters for PM package employees in Anantnag’s Vessu. It was Sunny Raina and Sandeep Pandita who took the initiative. Around a hundred families living inside the CRPF-secured quarters visit this temple. It has become central to the community’s culture.

They are trying to recreate their life before the 1990s—only now, under 24/7 vigilance.

“We are replicating the old Kashmiri life and showing our children how we lived in the valley. So that we can permeate those values,” said 40-year-old Raina.

Sunny Raina came to Kashmir as a PM package employee in 2010. In the beginning, rooms in the still-under-construction quarters were shared by three young KP men, including him. Over time, they got married and brought their families. And in those two-room quarters began a new chapter of Kashmiri Pandit life— living in Kashmir, yet never fully part of it.

The idea to build a temple inside the government quarters came after Raina closely followed the temple revival process across the valley. “We discussed with the elders, and it was decided that instead of visiting far-flung temples, we should build one here. Temples were why we were kicked out. Temples are how we will return,” said Raina.

Raina said that Kashmiri Pandits aren’t allowed to leave the quarters after 5 pm. The CRPF cites security reasons. So after the sun goes down, the temple becomes the gathering spot for the community. The elders hold Gita sessions every evening. Women gather to discuss their day. And children assemble for Kashmiri language speaking classes.

Raina is also a part of the community temple revival network. From monitoring temples, arranging labour to visiting government offices, Raina and several young men like him are taking the revival process forward.

Hundred kilometres away in Baramulla, North Kashmir, another PM package employee, Rohit Raina, has created a record of temples in Kashmir, categorising them as active, non-active temples, and abandoned. Rohit has actively participated in the revival of temples in Baramulla.

“All ten districts in Kashmir have their own temple committee. The idea is to strengthen the active temples. Do hawans at least once or twice a year in non-active temples. And the abandoned temples are being revived by district committees,” said Raina.

And now, Raina has taken up another task: He is calling Kashmiri Pandit families living outside Kashmir to visit their temples at least once a year. He is individually reaching out to the families, dropping elaborate WhatsApp messages and making video requests.

“When the families visit, it will renew their old love for the valley. That’s how the process of revival will start,” said Raina.

The Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museums have also made efforts to restore historic and heritage monuments, including temples.

Also read: Young Kashmiri Pandit creators haven’t forgotten haak and Herath. They won’t let you either

Govt schemes for revival

It was September 2014, and Kashmir was drowning in floods. In Anantnag’s Logripora, a desolate Kheer Bhawani temple was overtaken by raging waters. A tent nearby sheltered two dozen Kashmiri Pandit devotees. All of them battled the rising floodwaters to rush into the temple, where they stayed through the night, chanting prayers. Sandesh Bhat was one of them.

It was during that night that the community members of Logripora resolved to revive the temple. Today, the Kheer Bhawani mela celebrations here attract over 200 devotees. Most of these devotees once lived in the area. The dharamshala was built after almost five years of gathering funds and reconnecting with the community.

“In 2011, we performed the first hawan in this temple after the exodus. The idea was to first activate this place. The district administration gave us the tent, but we later built a hall for our stay in 2018,” said Sandesh Bhat, a former resident of the area.

Since then, Sandesh Bhat and fellow resident Manish Bhat have been knocking on government doors for funds. Last year, Rs 3,24,57,000 was approved by? the Directorate of Archives, Archaeology and Museums for the construction of the Kheer Bhawani temple at Logripora Ashmuqam in Anantnag district.

“Now, with this, we will have a yatri niwas, the hawan shala will be renovated. Stairs will be built for the shiv temple above,” said Manish Bhat, pointing at the lush green mountain.

In 2021, the Jammu and Kashmir government launched a policy for the revival, restoration, preservation, and maintenance of architectural and heritage sites across the Union Territory. This became a turning point for Kashmiri Pandits, as several of their temples came under the ambit of the policy.

In the last three to four years, several temples—including Ganpatyar, Ram Mandir, and Hariparbhat in Srinagar—have been revived. Around 30 temples have been restored across the valley. The department is also restoring shrines, mosques, and all other monuments of cultural and historical significance.

Last year, the J&K government sanctioned over Rs 17 crore for the renovation and upgradation of 17 temples and shrines in the twin districts of Anantnag and Pulwama in South Kashmir.

Also read: Kashmiri Sikhs ask how to stop losing daughters to Islam— ‘It’s a threat to demography’

Residents or migrants

At the Kheer Bhawani temple in Anantnag’s Logripora, long queues have formed at the open food stalls serving green collard, lotus stem, and dum aloo. Kalash Doon (walnuts in sacred water) are being distributed. A light drizzle falls, making the land slippery. People walk cautiously, while a banner of the Logripora Kashmiri Pandit Committee hangs on a wall nearby.

A few Muslims from the neighbourhood have come to greet the Pandit families. Some families show relatives the festival over video calls, while others reminisce about their childhood visits to the temple.

“Dekho hawan kund ko, jai karo, sab acha hoga (Look at the hawan kund, bow to God, everything will be fine now),” a woman says to her son on video call.

Ramesh Bhat has also travelled from Tral to attend the mela. A group of men and women listen intently to his stories of reviving the Nowdal temple. As he reminisces, a tear falls on his white kurta. “My mother would visit Nawdal temple every day,” he said, fumbling over his words.

An hour away in Ganderbal, the main Kheer Bhawani temple teems with devotees. Around a thousand have gathered in one large hall, packed tightly together. The pungent smell from the single urinal on site permeates the air. A board reads: “Kheer Bhawani Yatris.”

An old man, a blanket wrapped around his shoulders, repeats these words like a tape recorder stuck on loop: “There was a time we lived in our houses in Kashmir. Now we are in this hall as yatris. We are yatris. We are YATRIS,” he shouted.

At his home in Srinagar, Sanjay Tikoo, president of Kashmiri Pandit Sangarsh Samiti (non migrants), is watching a video of devotees at the Kheer Bhawani temple on his phone. He never left the valley. During the early 2000s, he with his team revived four temples in the neighbourhood. But he was not able to maintain them.

“We activated the temples. But maintenance required visiting the temple every morning and evening. We were not able to do that. And the temples went into an abandoned state again. This is because we are fewer in number in the valley,” said Tikoo.

This experience has made him pose a larger question: We are reviving the temples. But will the community be able to maintain them?

“There are hardly 300 families in the valley. Who will look after these temples? After a few years, they will be abandoned again,” said Tikoo.

At Logripora, Manish Bhat remains optimistic. “The temple revival brought our entire village together. We visit our temple every year and spend days on our ancestral land.”

“And in a few years, we will return for good.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Kashmir needs a truth and reconciliation comission. Like South Africa. Also some form of affirmative action from the state majority community towards the Pandits. Years of torture need to be recompensed.