Bengaluru: A 200-page case law book lands with a thud before Anusha, a 21-year-old visually impaired law student in Bengaluru. She runs her fingers over the pages, only to realise the text isn’t in Braille. While classmates around her flip open their books, Anusha sits quietly, waiting for the talking laptop promised by the Karnataka government. It’s her key to keeping pace in class.

Over a year ago, Anusha filled out an application on the state Seva Sandhu portal for the device, which includes an audio keyboard and specially developed software. She visualises herself opening the laptop, listening to the device read out important cases.

“As law students, we are given lectures on human rights, but my basic right to education is being taken away,” said Anusha.

The Department for the Empowerment of Differently Abled and Senior Citizens in Karnataka is responsible for providing hearing aids, Braille kits, and ‘talking laptops’ for students (Class 10 and above) and senior citizens under 14 schemes. This year, however, the programme faced a debilitating 80 percent budget cut—the first in a decade. The allocation dropped from Rs 53 crore last year to Rs 10 crore for 2024-25, amid a backlog of applicants waiting for their devices.

Visually impaired students are hardest hit, with the funds for talking laptops facing the steepest decline compared to Braille kits, hearing aids, and battery-operated wheelchairs. This is hurting students during their most critical years of schooling.

Anusha is one of over 250 visually impaired students in Karnataka still waiting for their Braille kits and talking laptops for the 2023-24 academic year. The backlog continues to grow—over 500 students have applied for talking laptops, yet only 35 have received one, according to the National Federation of the Blind, which has been protesting against the budget cuts.

Officials from the empowerment department acknowledged the delays, but dismissed it as a “routine administrative issue.”

“We are facing severe budget constraints. Hence, we haven’t been able to provide the benefits on time,” said Ashwathamma C, deputy director. She added that students can apply again in 2025.

Special educators and students have reverted to traditional methods—using online text-to-audio converters and clay models. Some have resorted to fundraising to provide Braille kits.

“Assistive technology opens a new chapter for students and bridges the learning gap in classrooms. But our lawmakers aren’t prioritising the empowerment of the disabled. Teachers and students are left to fend for themselves,” said Nagasamha G Rao, a child rights activist.

Making science touchable

Sitting at a stall outside his home in JP Nagar, Eresh, a Class 12 student, waits for his phone to buzz with class updates. It’s a signal that it’s time for his daily 3-4 hour-long study session.

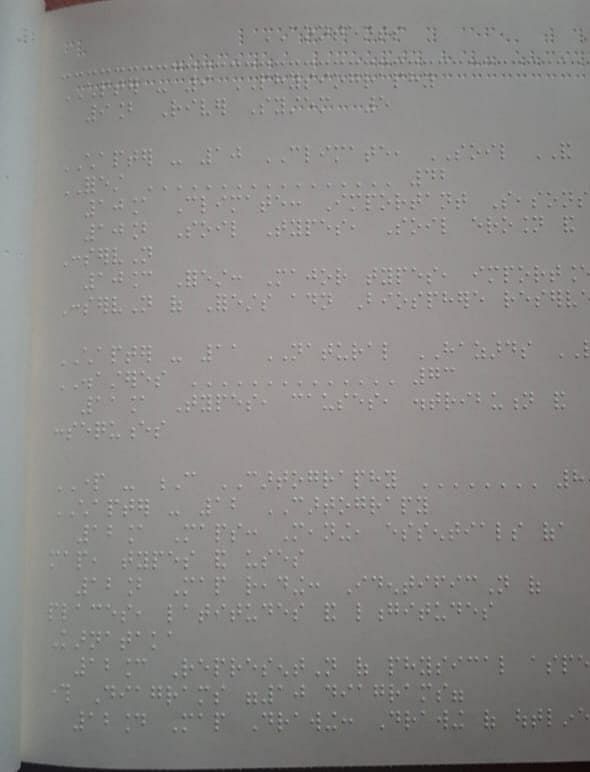

On the WhatsApp group ‘Class 12 PDFs’, Eresh’s friends and teachers share scanned PDFs of reading material. Eresh then downloads an app on his smartphone to convert text to speech. He then transcribes his notes into Braille using a stylus on paper, a painstaking process that takes twice as long compared to his classmates.

Eresh applied for a talking laptop and Braille kit in August 2024, but has yet to receive them. The mobile apps he uses are either expensive or limited to five free conversions. But it’s his only option to stay on track with his studies.

“This way I am at par with my friends in my class,” said Eresh, while mechanically pressing dots into paper. He was learning about electromagnetic induction. “Physics is my favourite subject,” he said.

For many visually impaired students in India, pursuing science remains a challenge. Few students continue studyingScience and Mathematics past the seventh grade, largely due to the lack of assistive technology. A study from Vision Empower Trust, an NGO for inclusive education, shows that assistive technologies are crucial to helping students tackle complex subjects like chemical equations and diagrams.

I don’t think I will get my laptop, as promised by the government, anytime soon. So I have no choice but to rely on this phone

However, educators have come up with creative solutions. For instance, Lakshmi, 45, prepares tactile diagrams of the reproductive system of a flower using Wikki Stix or clay and parchment paper for Sharda, a 16-year-old student who was born blind.

“It takes at least two hours to prepare these diagrams, but touching, feeling and sensing is the best way to learn. [Sharda] once came and told me that she scored full marks in her Science internal exam,” Lakshmi said while creating a tactile diagram of the human eye for Sharda’s next tuition class.

Sharda reminisces about her high school years at the Jyothi Seva Home for Blind Children in Bengaluru, a time when Braille texts and adaptive technologies like screen readers were more readily available. Now, she has to rely on guess work and audio instructions from her teachers. She feels out of place during lab experiments and quietly listens to her peers excitedly react to chemical reactions.

Similarly, Anusha had to leave Deepa Academy and move to The University Law College in Bengaluru to complete her five-year LLB programme. While her teachers dictate notes to her separately, she uses her phone with a screen reader app for most of her reading.

“I don’t think I will get my laptop, as promised by the government, anytime soon. So I have no choice but to rely on this phone,” she said.

As she tries to open the app, her phone hangs. “It’s okay. I have learned to wait,” she said.

A scheme in decline

When talking laptops were first distributed in 2014, then-Chief Minister Siddaramaiah hailed the scheme as a significant step toward inclusive education. Lamaria, a 15-year-old from Meghalaya, was one of the first beneficiaries. After the death of her parents, she moved to Bengaluru to live with her extended family.

“Even though the rules stated that beneficiaries must have resided in Karnataka for 10 years, the government took it upon themselves to help Lamaria. Today, she has successfully completed her education and is working as an HR professional,” said Sandesh HR from Enable India, an NGO that provides reading software like non-visual desktop access (NVDA), an open-source training platform called EYE tool, and its own spelling tool for the talking laptops. The NGO was the first to suggest the idea of such laptops to the government.

At the time of its launch, around Rs 4 crore were earmarked for the scheme. Initial laptops had images of Siddaramaiah, who had then said, “It is wrong to treat physically challenged persons as a burden to society or as useless. They are intelligent and smart. The government wants to empower physically challenged persons by providing them opportunities for education, employment, and other rights.”

However, more than a decade later, the government has reduced its funding for the scheme to Rs 30 lakh.

The cut began in 2019-20, when only Rs 2.4 crore were allocated. There was a marginal increase in 2021-22—to Rs 3.9 crore—after the Karnataka High Court questioned the state government about the non-distribution of talking laptops. Even then, 207 students out of 596 applicants did not receive their laptops, according to data provided by the Department for the Empowerment of Differently Abled and Senior Citizens.

“These are not freebie schemes,” said Gautam Agarwal, general secretary of the National Federation of the Blind. “They are the commitments of any elected government to uplift one of the most vulnerable sections of society.”

The federation has been organising protests across Karnataka against the drastic fund cuts since December 2024. Agarwal pointed out that such cuts have happened when the average price of a talking laptop has increased.

Ten years ago, a laptop for the visually impaired cost Rs 45,000. Last year, it was Rs 96,000

“Ten years ago, a laptop for the visually impaired cost Rs 45,000. Last year, it was Rs 96,000. The funds need to be earmarked in accordance with the market price. Many of these students cannot afford to buy such expensive devices by themselves,” he said.

In Tamil Nadu, the government has provided ‘Orbit Readers’—a refreshable Braille display and book reader and note-taker—for visually impaired students at a subsidised rate for over four decades. However, a 2024 study published in the Indian Journal of Educational Technology found that, out of ten surveyed schools, only four had screen-reading software with many students relying on NGOs for support.

When NGOs fill the gap

Mitra Jyothi NGO in Bengaluru was buzzing with activity on 26 November. There were celebrations for two young visually impaired women who had graduated from First Grade College in HSR Layout, while a laptop displayed the success of their tenth fundraising campaign in the past five years—‘Rs 5,01,574 raised of Rs 8,48,577 goal.’

NGOs and private organisations like Mitra Jyothi, Jyothi Seva, and Deepa Academy stepped up when government support for assistive technologies fell short.

The walls of Mitra Jyothi building complex in HSR Layout are covered with tactile design of the Karnataka state map and colourful embossed paintings created by blind students. The two graduates posed for pictures that would go down in the NGO’s history. Though they graduated from First Grade College, when asked which institute they belong to, they proudly say, “Mitra Jyothi.”

From providing accessible reading materials in eText, MP3, and Braille formats to paying their college fees, Mitra Jyothi has supported students by organising fundraising campaigns over the past two years.

“More and more visually impaired students are hearing about our services and reaching out to us. We are consistently hearing from children in rural areas who have not had access to technology,” said Madhu Singhal, founder of Mitra Jyothi and a champion of disability rights for over 30 years.

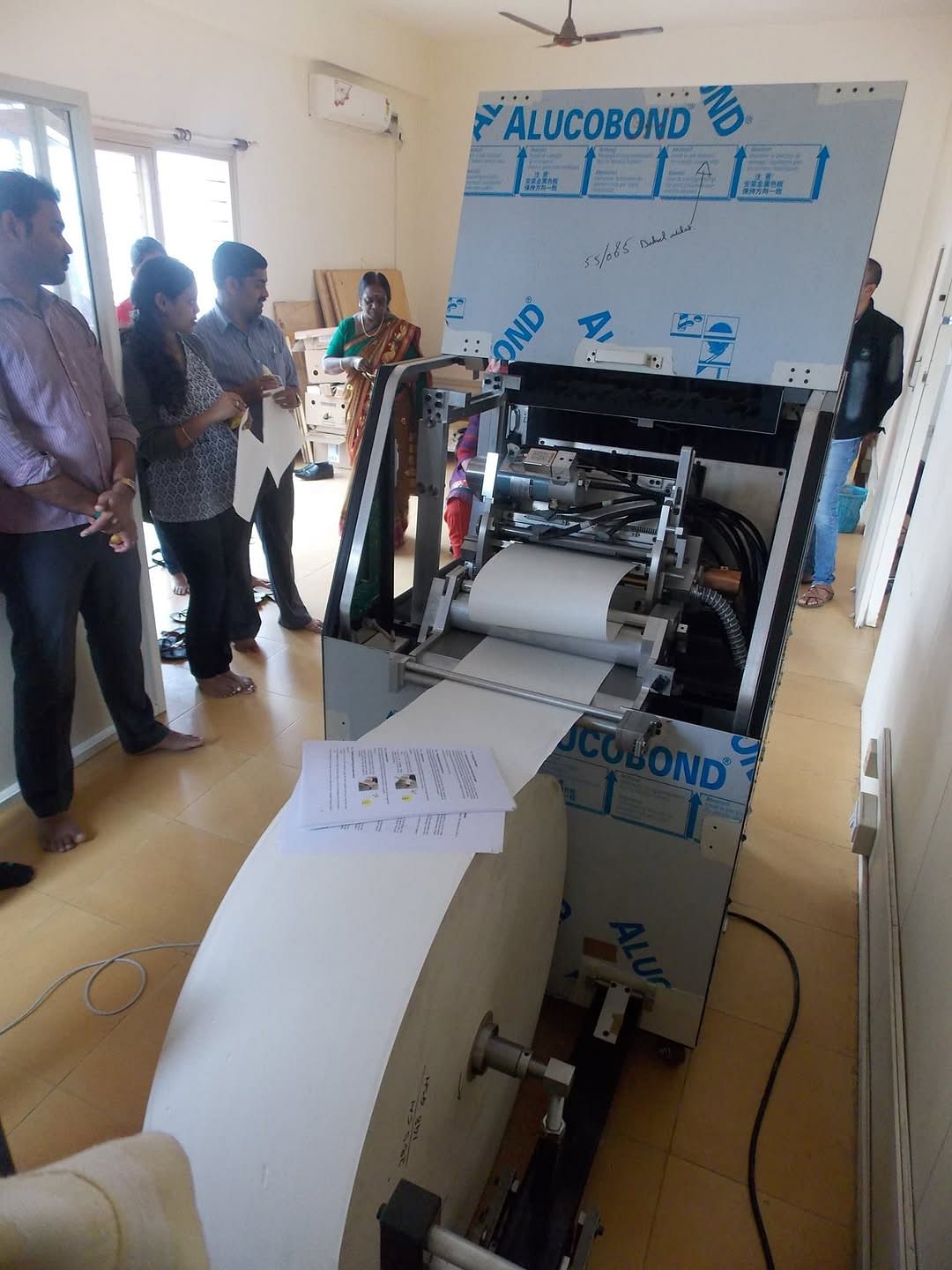

In a room within the NGO’s building, the Braille Transcription Centre device hums as it produces fresh textbooks. Nearby, keyboards clatter as adults learn computer skills, while lively cheers echo from the arts and crafts room on the top floor, where visually impaired women weave colourful mats and baskets.

Singhal recalled how many rural students hadn’t even heard of the state support scheme offering talking laptops and Braille kits. That is when she decided to support higher education for visually impaired girls from remote villages and disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. The NGO identifies six girls who have completed Class 10 and enrolls them in educational institutions in Bengaluru for further studies.

Currently, the NGO is running at least five fundraiser campaigns for its education support programme. “But it’s not always easy. The future of NGOs like ours remains in the hands of uncertain and irregular donations,” said Singhal.

Struggling beyond safe havens

For students aspiring to become lawyers, government officers, or pursue professions requiring specialised degrees, the path carved by NGOs often feels too narrow.

Nandini, who spent her early years at Deepa Academy, recalls it as a safe haven with easy access to Braille textbooks and audio recordings.

“I did not want to leave,” she said. Later, she earned a specialised degree in history, economics, political science, and arts at a government college—but received no assistance. She wasn’t allowed to record the lectures in class, nor was she provided with scanned copies of notes. She would make daily trips to a nearby xerox store to scan her classmates’ notes.

“But I couldn’t borrow notes frequently because my classmates also needed to study,” Nandini recalled.

She finally received her talking laptop five years after applying for it. By then, it was too late. She had completed her degree.

“I am now preparing for Karnataka Administrative Service exams, and the laptop has been really helpful. I can only imagine how useful it would have been if I had received it then,” Nandini said.

(Edited by Prashant)