Mangaluru: The sharp sun shining over Mangaluru’s Thannivari beach didn’t dissuade the family of 13 from Northern Karnataka, which has come here to enjoy a day by the sea for the first time. Men of the family take a dip in the waters along with kids, while women arrange towels and clothes, mind their shoes, and set up a picnic.

The western coastline of Karnataka with its pristine beaches and balmy sun should be on the Indian tourism map just like Kerala and Goa are, but isn’t. Despite five major rivers and tributaries, giant backwaters, surf-friendly waves and globally popular food, the coastal belt hasn’t caught the attention of even the most voracious travellers on Instagram. Lack of government push for tourism, patchy accommodation and an orthodox culture have left the region largely unexplored. It does not feature on people’s travel bucket list.

Most travellers here come for a day trip and don’t do much to boost the local economy. “We were all in Bengaluru and really wanted our kids to see what the sea is like. So we’ve driven down here only for today. We have very little time!” a 38-year-old woman said, while squeezing water out of her son’s clothes. The family will return home to Ballari the following day. They say they didn’t plan a longer vacation because they don’t know what else to do in the area.

“Our countryside beauty is intact. We have a lot of secret beaches and spots in the hills we don’t share with anyone,” says Yatish Baikampade

The problem could be that the people of coastal Karnataka are still not fully convinced that they should share their beaches with the whole wide world. There’s just not enough buy-in. Even tourism entrepreneurs talk of letting secret beaches be.

“Our countryside beauty is intact. We have a lot of secret beaches and spots in the hills we don’t share with anyone,” says Yatish Baikampade, a leader of the native Mogaveera community and a tourism entrepreneur.

The Marwanthe beach, adjacent to National Highway 66, is the most popular one on the stretch. In drone-captured images on Instagram, it looks serene and picturesque. While it is clean, and the drive to reach there is scenic, the beach itself is just a noisy stopover by a busy road.

Also read: In Ajmer maulana killing, children got the better of cops. Spotlight now on madrasa safety

Targeting of tourists

Moral policing incidents are regularly reported from Mangaluru, which has not helped coastal Karnataka’s reputation as a friendly vacation spot. The city is not yet ready for a thriving nightlife. “The city sleeps at 9 pm. Earlier, they had tried to set up some shops near Mangaluru’s beach and planned to open it till late at night but it didn’t work out. People just don’t like to be out late,” says Vidya Dinker, who heads the Citizen Forum for Mangalore Development.

“We don’t want booze overflowing on our beaches. We need to promote sustainable tourism,” says Yatish Baikampade.

Suresh Bhat, a former activist with People’s Union of Civil Liberties, has been meticulously recording incidents of communalism reported in Kannada language newspapers of Udupi and Dakshina Kannada districts for the past 14 years. He has divided this data into subcategories like moral policing, hate speech, cattle vigilantism, among others.

Bhat recorded 37 incidents of moral policing by Hindu and Muslim groups in 2021. One year later, the number of such cases increased to 41 and in 2023, it was 20. He says that young couples and students are targeted by vigilantes.

“Bus conductors, autowalas, hoteliers, inform vigilante outfits about the profile of people travelling and then such tourists are targeted,” Bhat says.

This year in January, two students were assaulted and harassed in Kadri park—the attackers even took their photographs and videos. In February, an interfaith couple was targeted at Panambur beach. In December last year, a group of friends was interrogated by local residents in Someshwar. The group had travelled from Ullal to visit the Someshwara temple and the neighbouring beach. While waiting at the bus stop, some local people identified that the students belonged to different faiths and started questioning them. Later, the police got involved, and it was reported that the students were from Kerala.

Even the students of Manipal University say they think twice before hitting the beach. “We try to stay in close quarters, within our campus, and go to places which are regularly visited by our college students,” a student says.

College students also venture out at night, driving to chai tapris for a cup of tea at 4 in the morning. “For a beach holiday, we travel all the way to Goa,” the student adds.

‘Don’t want to be Goa or Kerala’

A wave of counterculture movement in the aftermath of the Vietnam war in the 1970s and 1980s brought international tourism to Goa. It got a boost after the release of the 2001 classic Dil Chahta Hai, which attracted young groups to the tiny state, synonymous with fun in many tourist guides.

In the 1980s, Kerala got the tagline God’s Own Country, and became popular for its houseboats and backwaters.

When this tourism culture renaissance was going on in its neighbouring states, Karnataka’s coast was embroiled in riots. In 1993, riots were reported in Uttara Kannada’s Bhatkal town, which was put under curfew for two months. Three years later, the sitting MLA of Bharatiya Janata Party, Dr U Chittaranjan, was assassinated, fuelling further communal tension in the town. In these areas, especially post-riots, the Hindutva movement became a strong force.

The Mogaveeras, the fishermen community of Karnataka, are fiercely protective of their share of the Arabian Sea and don’t want tourism to affect their culture.

“There is territorial policing of the beaches here,” says Dinker. “The Mogaveeras think the sea is theirs to protect. They don’t let people play in the water for too long if they think that it could be dangerous. If they spot a couple on the beach for a while, they ask them to leave. They don’t want to ‘pollute’ the minds of their youth,” she adds.

Similar policing of beach goers takes place in areas such as Bengre and Ullal, which are dominated by the Muslim population.

“The beach here is dangerous. Both geographically and culturally. The sea is not as quiet as it is on Goa’s coast, and the culture on the beach is not as free either,” says BN Girish, who is the proprietor of the most popular hotel chain in the area, Ocean Pearl.

Girish has submitted a proposal to the central government recommending ways to boost tourism in the region. Among other things, he wants to bring casinos to Karnataka’s shores.

Girish isn’t the only person trying to encourage tourism in coastal areas of the state. Many want to ride the Kantara (2022) wave, which has generated unprecedented interest and enthusiasm among people across the country to visit areas in Tulu Nadu and explore the Daiva culture. Karnataka has a 350 kilometre long coastline that cuts across Uttara Kannada, Dakshina Kannada as well as Udupi districts.

There is no formal forum, but Girish is the most powerful hospitality-related person in the area.

Sport tourism

From the dangerous sea to the swelling waves that are perfect for surfing, there’s a perfect solution for a conservative culture that wants to earn revenue from its coastlines without embracing full-fledged beach tourism.

Some entrepreneurs, like Tushar of Shaka Surf Club in Kodi Bengre village in Udupi, have learned how to work with the local community.

Tushar and his friend Ishita opened the surf school in 2012, and have relied on the participation of their neighbours to run their operations smoothly.

“It’s about respecting a community that has existed for years and finding a balance where we can live and be part of the community without changing who we are, or expecting them to change their ways. When we first started, we requested women to not surf in a bikini and wear a t-shirt,” Tushar says. “As part of that balance we would request our students to wear a rash guard and shorts while surfing, since the village was not culturally accustomed to bikinis.”

Shaka Surf Club offers employment opportunities to nearby households, with different families preparing breakfast, lunch, dinner and tea for the school on a rotational basis. Shaka Surf also taught surfing to fishermen in the area, who are now trained instructors. It has given them an alternate employment opportunity.

Tushar and Ishita’s venture has made Kodi Bengre a bit of a tourist destination. It was one of the few places in the Udupi district with beach-side hostels, home stays, as well as houseboats for travellers. Since 2012, other ventures have also been established in the area. They explore water sports such as kayaking. It is still a small, largely unexplored village, and Tushar doesn’t want it to become more crowded.

Australian cricketer Jonty Rhodes agreed to be the surfing ambassador for India and also brought attention to the Karnataka coastline. India now has a surfing federation and international competitions are held here.

“We don’t want to be Kerala or Goa. We want Karnataka to have its own niche. Otherwise we’ll lose the peace and quiet here. Maybe that niche is sports tourism,” Tushar adds.

Baikampade shares the same sentiment.

“We don’t want booze overflowing on our beaches. We need to promote sustainable tourism,” Baikampade tells ThePrint.

Blue flag beaches

For years, Padubidri village in the Udupi district kept its beaches a secret from tourists. With billowing waves and clear blue water, the Padubidri beach has been the favourite place for the village’s residents. But the secret is out now.

Blue Flag is a certification awarded by the Denmark-based Foundation for Environmental Education to beaches that reach a standard of safety, cleanliness, and environmental regulation. There are two Blue Flag beaches in Karnataka — one in Udupi, and the other in Honnavar (Uttara Kannada). The Deputy Commissioner of Dakshina Kannada, Mullai Mullihan, tells ThePrint that the government is working to build the third Blue Flag in the district.

Now, an area of the Padubidri beach is earmarked as a government site. Officers don’t allow taking photographs of the sea here without the consent of the tourism department.

There’s a calmness on the beach, which remains elusive in urban or tourist-populated areas. There are no roadside vendors, or the clamour of ferrywalas. Just the uninterrupted sound of the sea.

Dolphins gallop across the Arabian Sea, children spot starfish and even jellyfish in the waters and run around screaming. The area is spic and span, with volunteers keeping a close eye on littering. The garbage that the sea brings is also cleaned regularly.

As part of a Blue Flag beach, the tourism department of Karnataka has built a park nearby. It has changing facilities, a washroom, lifeguards and government officials on duty. The tourism department charges Rs 50 for a mat to be placed under an umbrella, should one choose to lie down here.

“Blue Flag beaches get international acclaim to the state. They will make tourism on our shoreline more popular,” Mullihan says.

But there are naysayers of the scheme as well. “Why do we need a certificate from a European company?” Baikampade asks. “Just putting some installations near the beach and cleaning it doesn’t make it pollution-free; it is a gimmick.” He wants sustainable infrastructure development, an event calendar, and better promotion of Karnataka tourism.

Also read: Lajpat Rai wanted nation-building volunteers. Servants of People Society’s a spa, spice store

No push for tourism

People associated with hospitality in the area hope for a stronger tourism campaign by the government, along with a push for coastal tourism.

For now, Karnataka’s tourism campaign is ‘one state, many worlds’. While it succinctly captures the diverse geography of the state, Baikampade says it hasn’t struck a chord with the rest of India.

“We have a lot of temple tourists, we want to convert them into people who spend more time here in the district and also boost the local economy. We want them to explore the nature we have here,” Mullai Mullihan

The X handle of Karnataka tourism mostly retweets Incredible India posts. Other than that, the Udupi district has a tourism page where it describes itself as a place known for “religious fervour” and says nothing about its beaches. The other two coastal districts don’t have a tourism page on X.

Baikampade says that the state’s campaign is “lackluster”. “Nobody knows what our campaign is. There are no itineraries available online for places to visit. No push for tourism. Nothing,” he says.

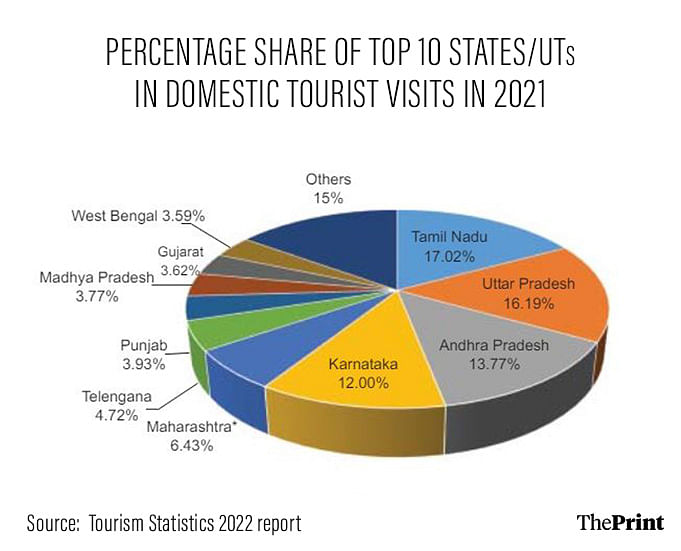

Karnataka is the fourth most visited state in India, according to the Tourism Statistics 2022 report by the Ministry of Tourism. According to the state’s action plan, 1$ Trillion Economy: Karnataka’s Vision, 5-10 million people visit Uttara and Dakshina Kannada every year, while 10-15 million people visit Udupi.

Most popular destinations on the coastline, including the ‘hippie’ Gokarna, are temple towns and attract religious tourists from all over the state. Udupi is known for Krishna Mandir, there’s a Ganesh temple in Gokarna, and Murudeshwar, a tourist destination in Uttara Kannada, is famous for the Shiv temple.

“We have a lot of temple tourists, we want to convert them into people who spend more time here in the district and also boost the local economy. We want them to explore the nature we have here,” Mullihan adds.

Deputy Commissioners are also in-charge of tourism in their respective districts.

Ocean Pearl’s Girish also gave a powerpoint presentation to the government officials. His proposal includes promoting Mangaluru’s food, heritage, beaches as well as a hill station.

In his presentation, Girish argues that Mangaluru is the only place where one can enjoy cuisines from Konkani, Gaud Saraswat Brahmin, and Tulu communities. He says that a lack of infrastructure, and laid back attitude toward tourism is hindering the development of Mangaluru as a tourist town.

“Localities and the people involved in the tourism chain are ignorant of hospitality. Taxi, auto, bus drivers, travel agents, restaurants are not so welcoming or hospitable to tourists,” he says.

Girish dreams of casinos on the shores of his city, development of beachside properties, a theme park, and houseboats to make the place the next go-to destination on travel itineraries.

“I have been to numerous meetings, but nothing ever moves forward. So now I have decided to build one Ocean Pearl in as many districts as possible,” he says.

“I don’t get a subsidy on fuel also, while registered houseboats in Kerala get 50 per cent subsidy on fuel,” says Rajesh Kamath.

In Udupi district’s Kodi Bengre village, 40 minutes from Mangaluru, five houseboats sit idly on the backwaters. They are struggling to attract tourists. Rajesh Kamath owns two houseboats that he built at a cost of Rs 3 crore, hoping for assistance from the government but never got any.

“I don’t get a subsidy on fuel also, while registered houseboats in Kerala get 50 per cent subsidy on fuel,” says Kamath, who runs the business with his wife.

Kamath built the first houseboat in 2017. It was designed by engineers who flew in from Kerala. Most of his guests are corporate clients who book the boat for parties. Sometimes, people from outside the state also drop in. But it is not that frequent.

“I charge Rs 2,000 per person for a package deal. The price is unchanged since 2017. People think even this is expensive,” Kamath says.

Mullihan says work to revive the Mangaluru tourism website is underway. Soon, people will be able to track cultural events for the calendar year and get recommendations of places and eateries to visit.

“We don’t have any beachside properties in the area. We will build them,” he tells ThePrint. But people of coastal Karnataka don’t want to share their shores with the rest of the world.

A beach-side cafe owner in Uttara Kannada, who doesn’t want to be named, says that while there are a lot of homestays by the sea, they’re not listed on Airbnb.

“These places (beach houses) are for people who know the area well. People don’t list them on Airbnb. That could attract undue attention,” he says.

Near his property, the police patrol all night. A small van and jawans are stationed at a crossing not far from the cafe — communal tensions were reported from this area just last month.

While people bank on tourism to push the local economy, many don’t want this part of the country to be discovered by littering tourists.

Residents go for long drives to have tea by waterfalls in the middle of the night, or they find spots on beaches to stargaze.

“Let’s let this place be,” Tushar says.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

? nice